|

This month’s blog is in response to an increasing number of requests, queries and comments I receive concerning surnames. The most common queries involve spelling, or why ancestors can’t be found, but with more and more men testing their Y-DNA either to solve a mystery of an unknown male ancestor or to uncover more about the origins of their patrilineal or direct male line, test results are throwing up more questions than ever; Why do I not know any of the matches with my surname, why are there different surnames in my matches, why is my surname not amongst my matches. Surname SpellingsQuestions or comments regarding the spelling of surnames continue to crop up regardless of countless blogs and articles on the topic. I would be rich indeed if I had a penny for every time I heard, they can’t be related as their name is spelled differently! Therefore, although one rule by no means fits all and there are always exceptions, I shall try to set out a few pointers. Top Tips regarding Surnames in Documentary Evidence

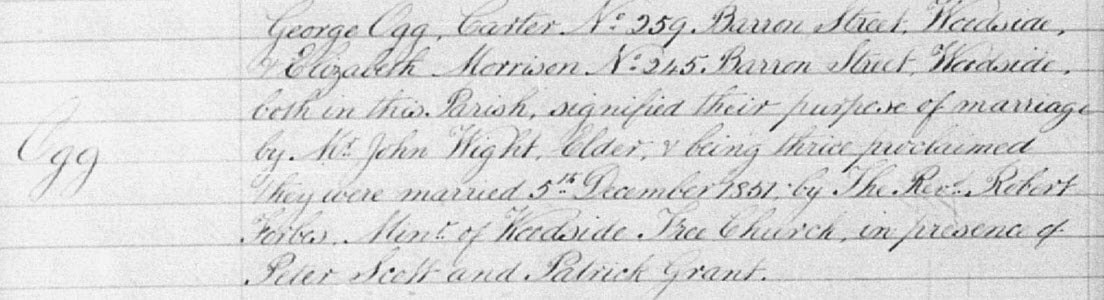

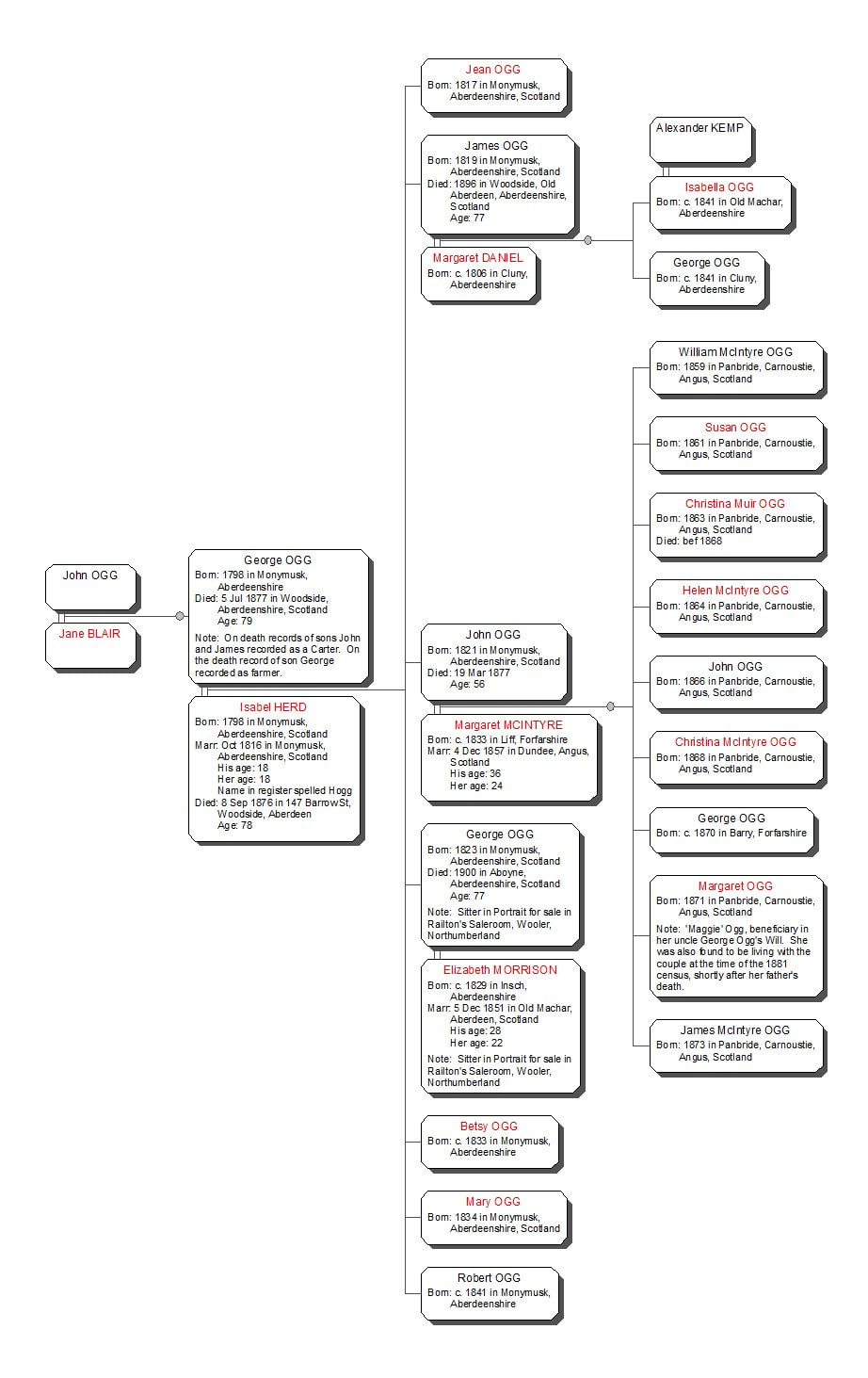

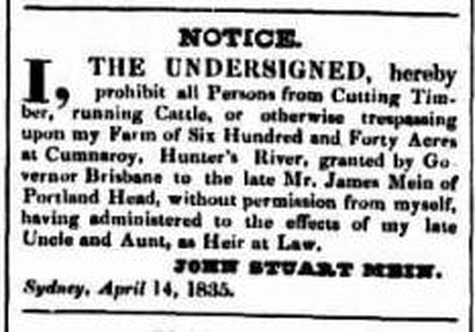

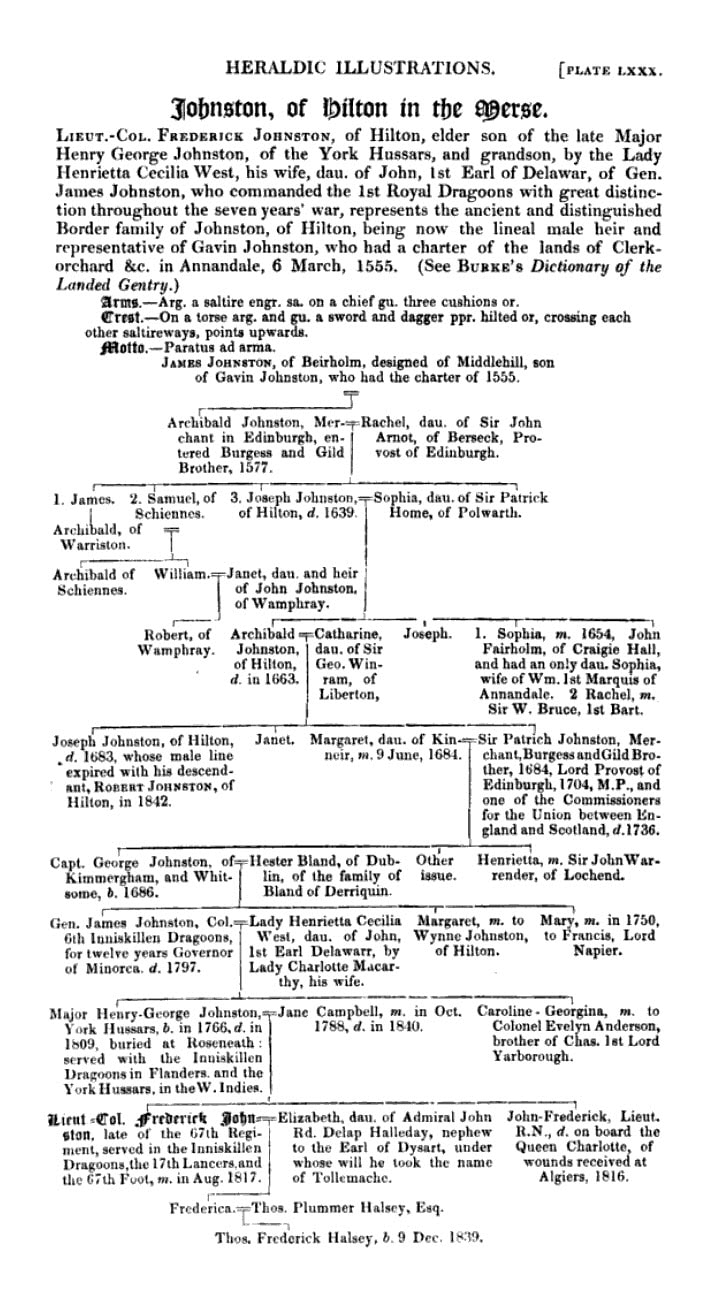

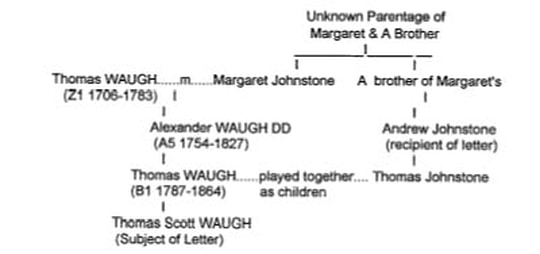

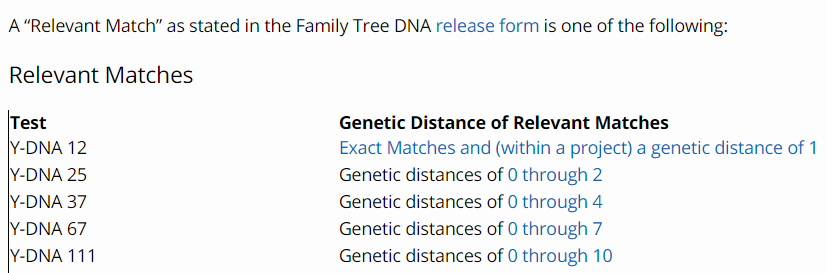

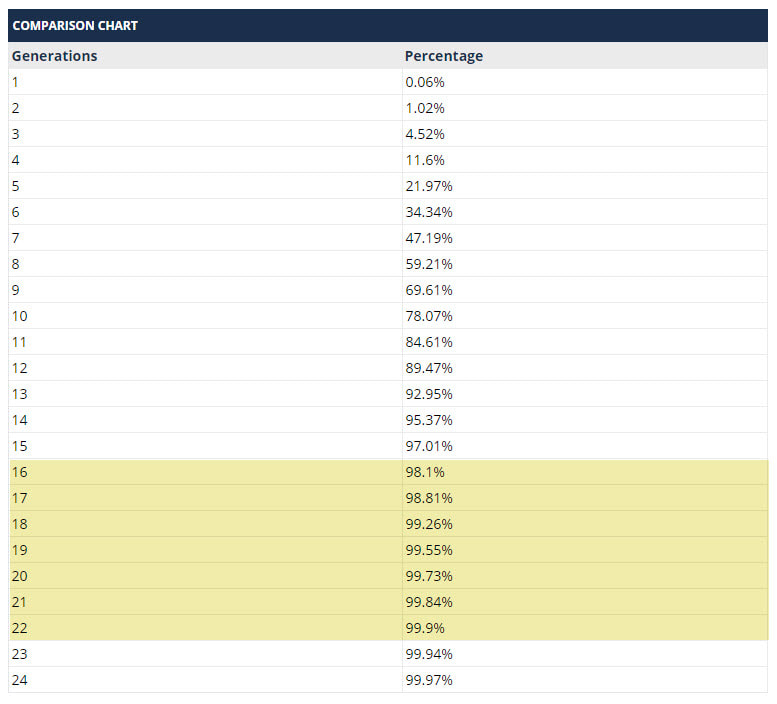

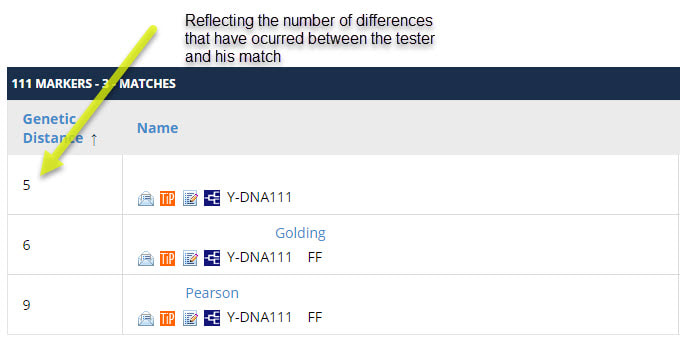

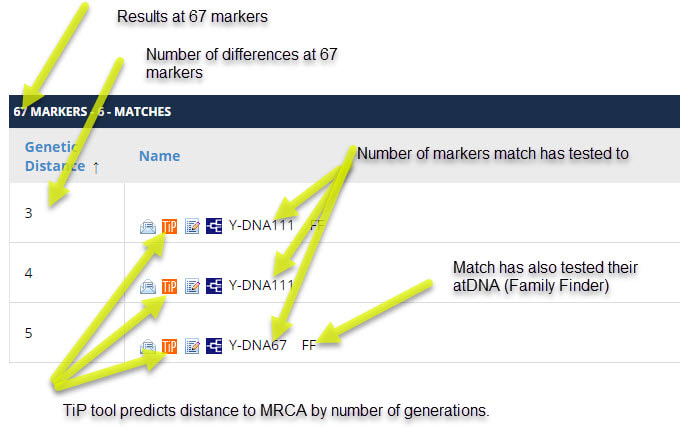

Y-DNA - The Test for SurnamesWhilst the numbers of men testing their Y-DNA remains relatively small, the test is increasing in popularity and the numbers of testers is increasing rapidly. The relative paucity of testers accounts for one of the most common reasons for a lack of matches sharing a surname. The environment and way in which results are presented is also rather different to at-DNA and gives rise to other specific questions relating to surnames, or perhaps lack of them! Y-DNA is the definitive test for ‘surnames’ as it is limited to male testers only as it passes solely from father to son and is neither inherited nor carried by women. It works by testing either STRs (Short Tandem Repeats) or SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) on the Y chromosome. The introductory test for investigating a surname using Y-DNA is the STR test which tests numbers of STR markers 12, 37, 67 or 111. The higher the number of markers tested the more accurate the prediction becomes regarding in which generation the match with another tester has occurred. The Family Tree DNA programme has parameters for returning potential matches based on the number of differences (Genetic Distance) that occur on markers between two testers, subject to the level of markers tested. In such a way matches which differ on more than one marker in 12 tested, two in 25, four in 37 tested etc., will not be shown as matches at those levels. However, the more markers tested the greater the tolerance of differences. By the time 111 markers are tested, matches with up to 10 differences (a genetic distance of 10) will be returned. However, if 5 of these genetic differences occurred on the first 37 markers tested, that particular match will not show in the returns of the tester at that level of testing. Whilst Y-DNA can predict the closeness of a relationship, it is unable to pinpoint the exact individual in the same way that autosomal DNA testing can. The FTDNA programme uses genetic distance (GD) or the differences, and on which markers they have occurred (some markers mutate far quicker than others) to estimate the number of generations that separate the tester and a match from their most recent common ancestor (MRCA). This is returned using the ‘Time Predictor’ or the ‘TiP’ tool which gives the time frame in generations. A generation usually equates to between 20 and 30 years, so by saying a generation equates to approximately 25 years, and, multiplying this by the number of generations predicted by the FTDNA TiP tool, will give an approximate timeframe to MRCA in years. See example from Pearcy DNA Project below: Pearcy (and variant spellings) DNA Project As reported back in August, David Pearcy tested his Y-DNA in order to delve into his deeper paternal Ancestry. He had one very interesting match with the variant surname of Piercy, whose family were known to have come from a similar geographical area in Northumberland. Initially the match had only tested to 12 markers, but crucially there were no differences at this level. The match then extended the number of markers tested to 111. This returned a genetic distance (GD) of 5. This equates to 5 differences, 1 of which occurred between 12 and 25, another between 25 and 37, a further 2 appeared between 37 and 67 and the final difference occurred between 67 and 111 markers. Using the TiP tool and extending the results displayed to every generation rather than grouping them to four years enables a greater degree of ‘estimation’ as to how many generations have passed since the MRCA lived. Using a percentage of between 98 – 99.9% (but may be more, or may be less accurate) places their most recent common ancestor somewhere between 16 and 22 generations, or very approximately, to have lived 400 & 550 years ago. For me personally, this is quite exciting as it suggests the Pearcy family had an established surname and were living in a close geographic area around Wooler & Ford in Northumberland around the time of the Battle of Flodden in 1513. To draw any more meaningful conclusions however, we need a far bigger Y-DNA sample from male Pearcy/Piercy/Percy & other variant spellings from around the globe. David and I have created a Pearcy DNA project through Family Tree DNA so if you are a Pearcy, or know a Pearcy then please either get in touch or point them in our direction. It is open to all, not just Y-DNA testers, and is completely free to join. https://www.familytreedna.com/groups/pearcy-piercy-dna-project/about (Please note, you will also need to sign-up to Family Tree DNA to join the project if you have not already done so. You do NOT need to purchase a DNA test from FTDNA to join. Registration is completely free of charge at www.familytreedna.com/autosomal-transfer & you do not need to transfer your atDNA if you do not wish to.) Top Tip – The Genetic Distance in Y-DNA Test ResultsThe Genetic Distance figure given by FTDNA reflects the number of DIFFERENCES that have occurred between two testers, NOT the number of generations. To find the estimated time lapse to the most recent common ancestor shared with a match, USE the TiP TOOL. This gives the estimated time lapse in generations. To approximate this in years, multiply by 25. Common Question - Matches of the same surname as myself match me at 12 markers but not 111The most common reason for this is that the genetic distance becomes too great to be relevant and therefore the match at 12 markers is dropped from the match list at higher levels of testing. Another very common reason and one which is easily overlooked is that the match hasn’t actually tested to the same number of markers as yourself. Top Tip – Check the level the match has tested to.Look at matches with the same surname as yourself and check the level that match has tested to. This information appears after the match’s name. If they have tested to a much lower level than yourself this may be one reason why they do not appear at a higher level. This can be remedied by the match raising the number of markers they have tested. In most cases there is no need to retest and the sample supplied for initial testing can be used. Y-DNA Matches with Different SurnamesAny form of DNA testing carries the risk of unearthing unwelcome family secrets but there are many other reasons why any DNA test may not yield the results expected. Second families, adoption and illegitimacy are just a few. In Scottish clan projects, DNA that fails to match with the surname of the chief also results in unnecessary disappointment for some. Whilst kinship was at the core of the clan system, many clan followers or dependents adopted the name of the ruling family even where there was no blood tie. Daughtering Out & Inheritance Another reason surnames may not reflect those expected can be due to a change of name. Historically this sometimes occurred amongst landed families when it became extinct in the male line, in other words ran out of sons or other immediate male relatives of the same surname. Those inheriting the land or heritable estate may have descended down the female line and changed their name on inheritance. A change of surname to reflect maternal line inheritance is a topic I have touched on before, when Thomas Wood assumed the surname of his uncle Shafto Craster on inheriting the estate in 1837. (The Christian name Shafto itself being derived from a surname.) There are also instances where younger sons in landed families have inherited from mothers or grandmothers and have relinquished their patrilineal surname in favour of the female line from which they have inherited. A prime example of this is John Ogle, (younger son of Robert Ogle d.1410) who on inheriting the castle and manor of Bothal brought to the Ogle family by his grandmother Helen Bertram adopted the surname Bertram himself. Helen was herself a sole heiress so John in adopting her patrilineal surname for himself resurrected a line which had itself become dormant in the male line. The most common reason a Y-DNA match does not share a surname, however, is that it predates the introduction of surnames themselves. Surname Origins As research progresses back in time it inevitably reaches a point where surnames cease to exist or have not followed the hereditary pattern of today. Hereditary surnames, or where the same surname passes unchanged down through subsequent generations in the male line, came into use following the Norman invasion of 1066. Before this time, and indeed in some places for some time afterwards, ‘surnames’, second names ‘cognomen’ or ‘bynames’ followed the Anglo-Saxon tradition which was more akin to an ‘identifier’ within a community and changed with every passing generation. They were often drawn from places names, topographical features, occupations, patronymics (son of ‘x’), less commonly matronymics (son of ‘x’ female), nicknames and personal idiosyncrasies. As the first ‘national’ survey undertaken in post-Norman Britain, the names recorded in the Domesday Book are therefore indicative of the early surnames in use at that time. An interesting study into Anglo-Saxon bynames recorded in the Domesday Book by medieval historian Thijs Porck, can be found at Anglo-Saxon bynames: Old English nicknames from the Domesday Book. The contents of the Domesday Book can be found online at the ‘Open Domesday’ with more information about at ‘The Hull Domesday Project’. The Domesday survey was neither representative of the population (as it only listed those with landholdings), nor did it encompass the whole of England. As can be seen from the interactive map on the Open Domesday website, Northumberland and Durham were notable exceptions. The earliest ‘Domesday’ equivalent for the region is the ‘Boldon Buke’ a survey undertaken approaching 100 years later in 1183 on behalf of the Bishop of Durham, Hugh Pudsey. Surnames’ of any recognisable kind are absent, with those few individuals who have been named either identified as a ‘son of’ (filius) ‘Richard son of Ulkil’, ‘de’ meaning of a place ‘Adam de Thornton’ & ‘Wynday de Grindon’ or by a nickname or byname, ‘Elfald Langstirap’. Although the practice of hereditary surnames had been adopted and was in common usage in England by the mid fourteenth century, the north and in particularly the areas of the former Marches with Scotland were slower to follow suite. Dr Jackson Armstrong of Aberdeen University has made an in-depth study into matters of Lordship, Kinship and Surnames along the English border during the fifteenth century in his book ‘England’s Northern Frontier, Conflict and Local Society in the Fifteenth-Century Scottish Marches’. His findings and examples supporting the notion and depth of ties on kinship make fascinating reading and illustrate the significance of collateral paternal as well as maternal line inheritance. (I appreciate the book is not cheap, but for those of you serious about your ‘Borders Ancestry’ this brand-new book comes highly recommended. Part II will be of particular interest to those researching the riding ‘Surnames’ associated with the Border Reivers.) In his new study Dr Armstrong has used 15th century Gaol Delivery books as sources and evidence of use of hereditary surnames. He found that ‘The later Middle Ages were a transitional period in which older bynames co-existed with newer hereditary surnames as a type of cognoma. Consequently, it is not always possible to distinguish one from the other.’[1] As outlined earlier, by-names were drawn from ‘occupations, topographical features, toponyms the body and personal characteristics, animal names and interpersonal relationships denoting kinship (and so taking the suffix -cousin, -son or -daughter) among numerous other potential sources and combinations. Employment was one such source …’[2] Throughout the book Armstrong uses clear and interesting examples to illustrate his findings:

And uses of patronymic naming patterns used simultaneously alongside by-name surnames

And of double patronymic

Although Armstrong notes that these types of combinations are more uncommon in east of the region. He further notes examples of compound names

‘as reasonable to conjecture, described a family relationship by adding a patronym to a hereditary surname in order to assist with identification’.[3] By todays way of thinking the use of middle names may suggest the maternal line surname, but clearly in this 15th century context this is not the case. Extreme care must therefore be taken before drawing conclusions on early lines of decent, particularly where patronymic naming patterns are used.

1 Comment

‘Tithes’ – nearly everyone has heard of this historic form of taxation and associates them to with payments to the Church, but what exactly were tithes and why are their records so valuable to historical research? A ‘tithe’, literally meaning one tenth, at the inception of the tithing system in the 6th – 8th centuries, was essentially a tax on agriculture originally designed to benefit the established church and the clergy. Unlike other forms of taxation tithes were a burden born solely by those whose income arose from agriculture and the land, either directly, or indirectly. Before being commuted to a monetary equivalent by the Commutation Act of 1836, tithes were often paid in kind. They were based on ‘one tenth’ of the natural gain of a crop, herd or flock. They were, however, imposed on the gross product, with no allowance taken or made for seed sown, fertiliser or land improvement. By 1836, the method of collecting tithes in kind had become outdated and was no longer fit for purpose. The decision was made to abolish the ‘in kind’ system and replace it with equivalent monetary payments or ‘rentcharge’. (In Scotland, where Tithes were known as Tiends, a form of commutation had been introduced in 1663. Therefore, they were not included in the surveys or maps produced as a result of English reforms of 1836.) In truth, however, like anything that has been around for almost a thousand years, the ‘story’ of tithes before they were commuted to monetary payments in 1836, is rather more complex than it first appears As so often seems to be the case, those at the ‘top’ stood to gain far more from tithes than those at the ‘bottom’! But what exactly was subject to tithe payments and just who was entitled to what? Tithes could be subject to some degree of manipulation and regional variation according to land use, and, like some manorial customs, what was liable to be ‘tithed’ varied from parish to parish. Nonetheless tithes fell into three classifications; predial, mixed and personal. Classifications of TithesPredial Tithes These related to the ‘fruits of the earth’, so anything that grew in it, or from it, such as corn, hay and other crops. It also often included wood. These were the most valuable class of tithes. Mixed Tithes Mixed Tithes related largely to animals such as lambs, calves, colts, or to animal products such as wool, milk, eggs etc. Personal Tithes These tithes were payable on the gains of labour in related agricultural industries such as corn milling or fishing. Tithes were grouped further into Great Tithes and Small or Lesser Tithes: Great Tithes were paid to the Rector (administrative leader) of a parish, who may be a resident incumbent i.e. bishop, prior, prioress or an establishment such as a monastery, nunnery, college etc. These comprised the most valuable Predial Tithes or Corn Tithes. Lesser or Small Tithes were paid to the Vicar appointed to a parish and performing a parochial service. These tithes were drawn from the Mixed Tithes, so lamb, wool, eggs etc. Tithe Collection & SatireBefore the ‘Commutation Act of 1836’ when payments in kind were replaced by a monetary equivalent or rent charge, it was the means in which Tithes were collected and paid that many found so repugnant. Great tithes or corn tithes were often left in the field from where ‘tithe collectors’ appointed by the owner would arrange collection and/or sale. The recipient of the Lesser Tithes was also perfectly entitled and within their rights to enter a farm or property at any time to collect their dues. This custom naturally lent itself to satire, with the local ‘incumbent’ often the butt of the joke.

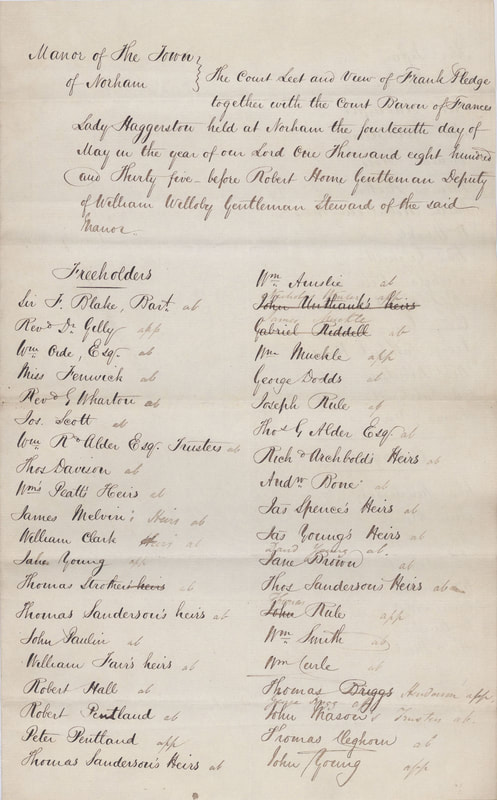

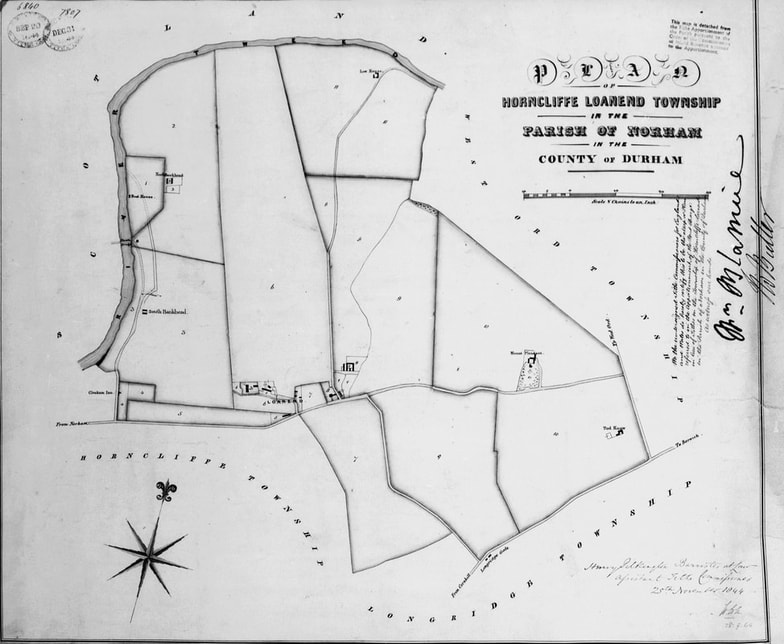

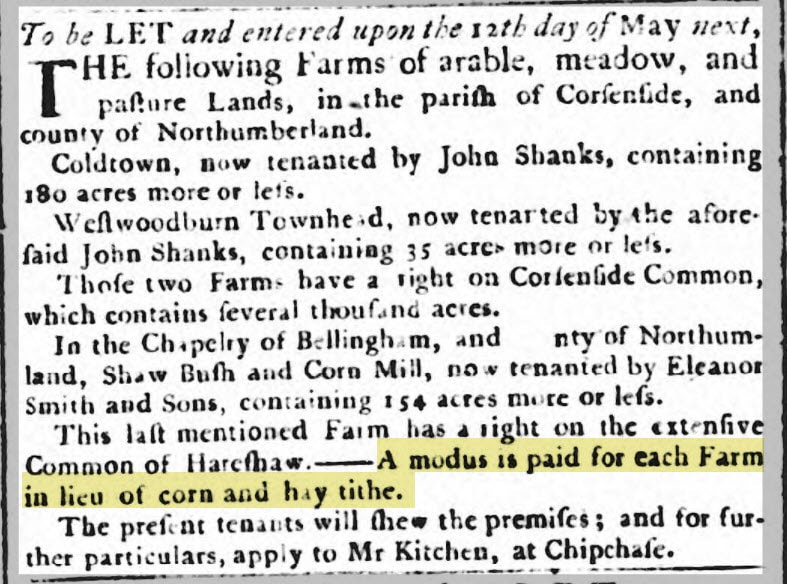

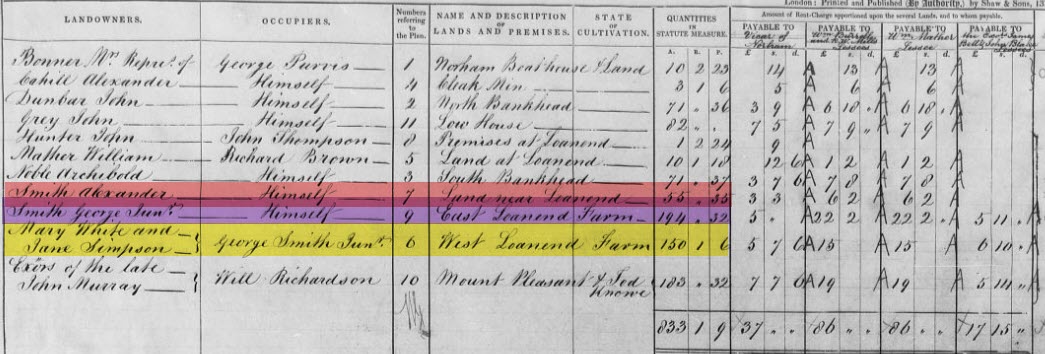

As a clergyman’s daughter, author Jane Austen was extremely familiar with the English tithe system and the topic of a clergyman’s ‘living’ often appears in her novels. Her obsequious character ‘Mr Collins’ in Pride and Prejudice ranked "making such an agreement for tythes as may be beneficial to himself and not offensive to his patron" his first and foremost duty as a clergyman. As a rector, like Jane’s father, her character was entitled to both the Great and Lesser Tithes of the parish, and to their collection. Humour aside, the payment and collection of tithes, particularly those made in kind has been described as a ‘vexatious impost’ and formed the root cause of many a dispute. However, tithes were not designed to be contentious, but more as a means of bringing communities together. In writing about the significance of Tithes during the eighteenth century, Daniel Cummins argues Although tithes could cause contention and friction, their real significance lies in the numerous relationships they created within eighteenth-century English society. These relationships constituted some of the most important everyday economic, contractual and social connections between individuals and were a central feature of parochial life during this period.[1] Impropriation & Impropriators In reality, however, the reformation and dissolution of the monasteries saw much Tithe entitlement pass from the church, to the Crown and from there into the hands of laymen (impropriators), in a process known as impropriation.[2] It has been estimated that in the period post-1530 up to one third of all great tithes were in the ownership of laymen. Furthermore, great tithes could be traded, i.e. bought, sold or leased by both the church and layman owners. … tithe purchase involved an agreement made before harvest. The tithe purchaser entered into a contract with the tithe owner by which he or she agreed to pay a certain sum for the bought tithes on appointed days. Tithes sold in this way made up a significant portion of all the grain which reached the market.[3] It is thought that by the time the Commutation Act was passed in 1836, 25% of the value of all tithes was in ownership outside the church. Tithe Records for Historical Study Tithes records are essential for the comparative study of acreages farmed, land use, cropping patterns, yields and crop values throughout history which is also helped by the uniformity of the ways in which the data was collected and compiled. I myself drew on the analysis of tithe data from Durham Cathedral Priory Muniments for evidence relating to corn production in the North East at the time of the Battle of Flodden in 1513.[4] For the Family Historian, however, the records and maps generated as a direct result of the 1836 reforms are of particular interest. Composition and ModusPayments in kind had been abolished in many areas before the reforms of 1836. Those made in monetary equivalents before 1836 came in two forms; a ‘composition’ which was subject to periodic revision, or termination by either party or a ‘modus’ which was a permanent charge attached to a particular product or piece of land. Where payments in kind persisted at apportionment, or had already been commuted to compositions or other monetary equivalents, specific details can often be found in the accompanying Articles of Agreement to the 1836 revisions. The records generated by the reforms produced, a map, an apportionment schedule and a file between the years 1841 and 1860. These records were also produced in triplicate: an original and two copies of every confirmed instrument of apportionment. The originals are now in The National Archives. The two copies were deposited with the registrar of the diocese and with the incumbents of and churchwardens of the parish. In many cases the copies and subsequent altered apportionments are now deposited in the relevant local record office.[5] The Genealogist & Tithe Records OnlineThe good news is that for those with access to the internet the records are also available online (along with other record sources unique to the site) with a diamond subscription to ‘The Genealogist’. Furthermore, the records can be searched by place, not just by person, so if your interest happens to be in a particular farm, village or town the tithe data provides a fascinating snapshot in time. Examples and snippets relating to Horncliffe & Norham Mains. As examples of the type of information that can be sourced from tithe records, here are a few snippets that I found useful in the course of research into my own family. It was already known from the records that over the years the Smith family had interests, both owned and tenanted in several farms around Horncliffe and Norham, most notably Loanend, however the information lacked specifics. The tithe schedule dated 1844 for Horncliffe provided the following information:

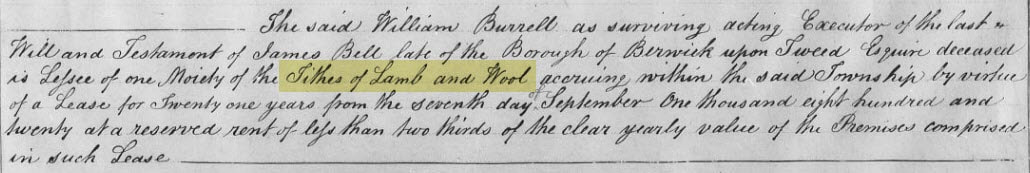

Accompanying Tithe Map from the 1844 Survey of Horncliffe Loanend. Reproduced courtesy of The Genealogist and The National Archives, Kew. Tithe Maps such as these are accessible online, along with many other unique record sources with a subscription to 'The Genealogist' https://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/ The land ‘owned’ and occupied by George Smith jnr at Horncliffe is represented on the accompanying map by the number ‘9’, and the land he occupied which was rented from his wife’s relatives by the number 6. (NB. It is more usual to see land owned and occupied represented by a series of numbers, not just one, with the land use of each parcel also given.) The Articles of Agreement relating to the apportion of tithes make fascinating reading too and are packed with additional information and local idiosyncrasies. Those arising from a meeting which took place on the 17th August 1839, relating to Horncliffe confirm that prior to the 1836 reform, Small Tithes with the exception of Lamb and Wool, which were leased from the Dean & Chapter of Durham by the Executors of James Bell of Berwick upon Tweed decd, had still been payable in kind. A modus of ‘one shilling’ had been in place as payable in lieu of hay tithes. Similarly, the ‘Articles of Agreement’ relating to the Tithes in the Township of Norham Mains confirm that payments had still be made in kind there too – both Great and Small, except the following for which ‘customary’ payments had been made as follows:

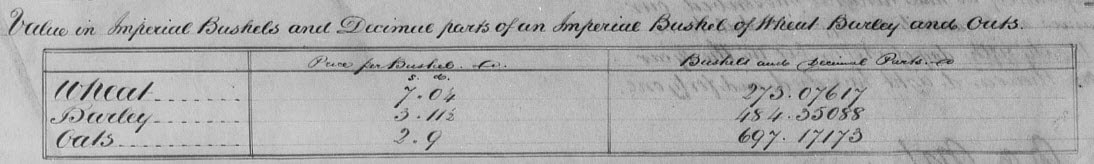

There is even more historical information which can be extracted from the records relating to the commutation of Tithes, not least the values attributed to corn, given in bushels.[6] There are many taxes from which historical information can be gleaned, but none have the longevity or depth of information as Tithes. The above is a just a brief overview designed to provide background, context and an explanation of a few of the terms that are likely to be encountered during your own foray into the world of Tithes and associated information. There are many excellent books and essays on the subject of the Tithe system, a few of which are listed below. In addition 'Tithe Surveys for Historians' by Roger J.P. Kain & Hugh C. Prince, Philimore, 2000 provides an in-depth explanation and background to the information the surveys will provide. Another very helpful overview is available from Family Search at https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/England_Tithe_Records_(National_Institute) [1] Daniel Cummins, ‘The Social Significance of Tithes in Eighteenth Century England’ The English Historical Review, Vol. CXXVIII No. 534, Oxford, 2013 pp

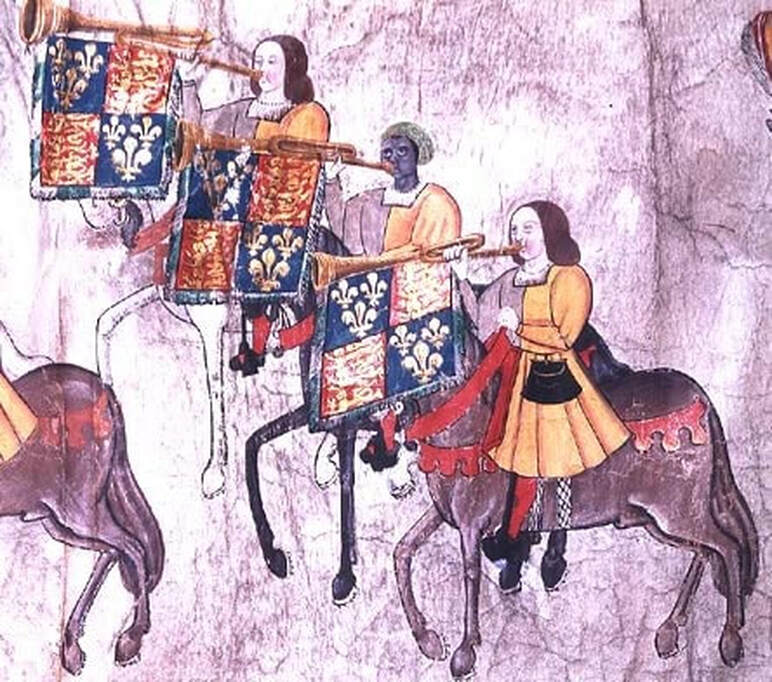

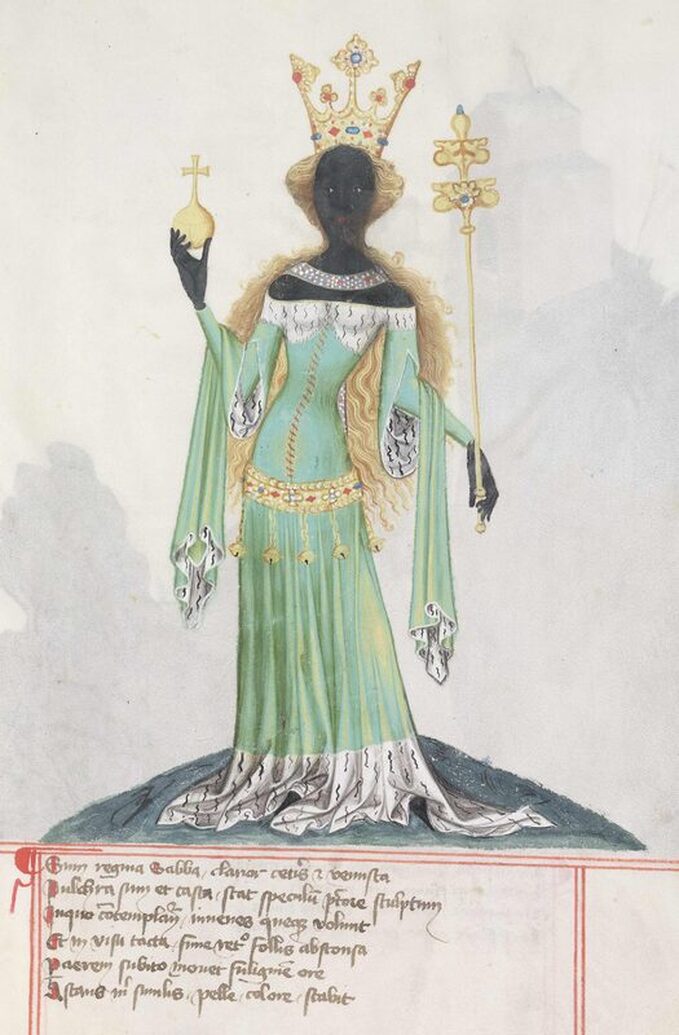

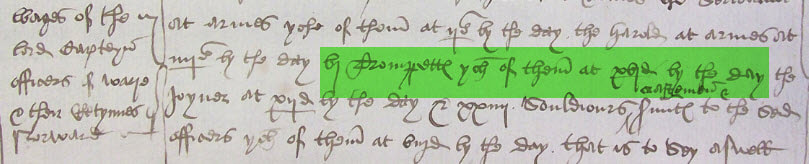

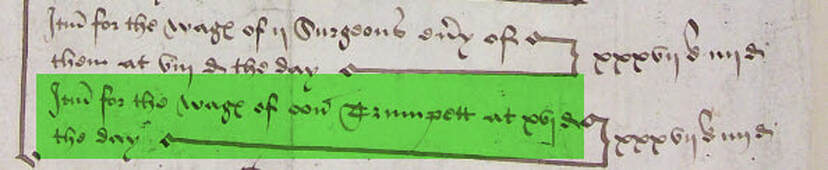

[2] When entitlement passed to the church or religious houses it was ‘appropriated’. [3] B Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants and Production in the Medieval North-East’, Regions and Regionalism in History, Woodbridge, 2007, p.162. [4] Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants and Production in the Medieval North-East’, Regions and Regionalism in History, Woodbridge, 2007; Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants, Landlords and Production between the Tyne and the Tees, 1349-1450’, Regions and Regionalisms in History, Woodbridge, 2005. [5] The National Archives http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/legislation/other-archival-legislation/tithe-records/ [6] There were approximately 8 bushels to the quarter and 4 quarters to the avoirdupois ton which equated to 20 cwt, or 2,000lbs, = 62.5lbs per bushel. October’s blog is inspired by both ‘Black History Month’ and references I encountered earlier this year whilst looking for some inspiration for a piece of fiction. I had been digging about in Historic Environment Scotland’s, medieval document research for Edinburgh Castle when entries relating to two ‘Moorish Lassies’, and the ‘Black Lady Tournaments’ of 1507 and 1508 had rather piqued my interest. The ‘Lassies’ are believed to have arrived by ship into Edinburgh, rather disturbingly, with a load of exotic animals, an African Drummer and other black individuals in 1504. Whilst Columbus had discovered the ‘Americas;’ in 1492 and the Portuguese were engaged in the slave trade by this time, neither England nor Scotland were actively involved in the trafficking of human cargo at this early date. As Church registers were yet to be introduced (1538 in England, 1553 in Scotland) these documents afford a rare glimpse into the lives of black people in Britain during the early sixteenth century. It is thought the ‘Lassies’ and other individuals may have been aboard a Portuguese Ship, captured by the Scottish High Admiral and Privateer, Andrew Barton, revenge for whose death at the hand of the Howards in 1511, is often recounted amongst the reasons for the Battle of Flodden in 1513. War by sea between England and Scotland was soon followed by war by land, and in the letter of remonstrance and defiance to Henry VIII., with which James preceded the invasion of England, the unjust slaughter of Andrew Barton, and the capture of his ships, were stated among the principal grievances for which redress was thus sought. Even when battle was at hand, also, Lord Thomas Howard sent a message to the Scottish king, boasting of his share in the death of Barton, whom he persisted in calling a pirate, and adding that he was ready to justify the deed in the vanguard, where his command lay, and where he meant to show as little mercy as he expected to receive. And then succeeded the battle of Flodden, in which James and the best of the Scottish nobility fell; and after Flodden, a loss occurred which Barton would rather have died than witnessed.[1] The Moorish Lassies and the Black Lady Tournaments The ‘Moorish Lassies’, and their fellow African passengers far from being slaves, were readily accepted into the Court of James IV and thereafter formed part of the Royal entourage. The ‘lassies’ who were called Margaret and Ellen were appointed as Ladies in Waiting to Margaret Stewart, the illegitimate daughter of James IV and Margaret Drummond, thought to have been born circa 1495. These were undoubtedly privileged positions within the young Margaret’s ‘royal’ household. She and her African ladies made a tour of the Borders on horseback in the autumn of 1504, where one of them is rumoured to have been baptised. As to the Black Lady Tournaments, there has been much speculation as to the role played by the two African girls, with some sources maintaining Ellen played the lead as the ‘Black Lady’, to James IV’s ‘Black Knight’. Others consider the girls acted in supporting roles as hand maidens to James’ daughter Margaret who herself played the female lead. There is also speculations that role was played by a gypsy woman ‘whose portrait survives among the collection derived from Piers the Painter (Andrea Thomas, Princelie Majestie: The Court of James V of Scotland (Edinburgh, 2005), p 83).’ A doubt about the genuiness of the Black Lady’s ‘African’ identity is raised by the black chamois sleeves which she wore as part of her costume. These were conventionally used as part of the Renaissance ‘blackface’ disguise in court masques. It is credible that they could also be worn for the purpose of modesty and warmth by a genuine African in the Scottish weather… The role might have been played by two separate people in the two different years and could even have been played by a man. Nor do the record of the tournament expenses give up the secrets – the documents maintain the illusion, recording the outlay on the clothes of the Black Lady, just as they do when recording payments for the unicorn pulling her chariot.[2] On both occasions the description of the costume worn by the ‘Black Knight’ would appear to have been a far departure from the traditional plate tournament armour, prompting some to hypothesise it was the King dressed as an African warrior or Ottoman nobleman of whom he may have learned from the ‘Moors’ at his court. The colourful pageantry of the tournament also included: Dragons, a unicorn and other unlikely animals … They may also have included animals from the Royal Menagerie which at this time included a lion and a wolf. [3] (The report and research undertaken by Historic Environment Scotland is available online as a pdf document and can be downloaded here) In terms of establishing the presence and roles of black individuals in Britain in the period before slavery, in my opinion there are two books that provide some very enlightening evidence. The first is Peter Fryer’s ‘Staying Power’ whose dramatic opening statement to Chapter 1 ‘There were Africans in Britain before the English came here’ cannot fail to garner curiosity, and the second is Dr Miranda Kaufmann’s ‘Black Tudors’, which given my own geekish fascination in the Borderlands in the early sixteenth century, reintroduced me to a certain John Blanke, a chap I had met before but through a palaeography exercise rather than the fact of him having been black! African Soldiers at Hadrian’s Wall Peter Fryer brilliantly positions himself to tell the story of ‘Blacks in Britain’ by beginning with evidence of African soldiers that served with the Roman Army and a division of Moors stationed at Hadrian’s Wall in the 3rd century AD. He further recounts the evidence of a certain ‘Ethiopian’ who dared mock the Libya born Emperor Septimus Severus in 210 AD near Carlisle. Having returned from a successful foray against the inhabitants north of the wall, Fryer tells us the emperor was less than impressed to ‘encounter a black soldier flourishing a garland of cypress boughs.’ To a Roman, the Cypress was an omen of death …, but I shan’t spoil the outcome of that particular tale and shall leave it to be read alongside the rest of Fryer’s fascinating book.  (Cropped) The national archives describe this thus: "an extract from the 60ft-long Westminster Tournament Roll, shows six trumpeters, one of whom is Black and is almost certainly John Blanke. All the trumpeters are wearing yellow and grey, with blue purses at their waists. John Blanke is the only one wearing a brown turban latticed with yellow. He is mounted on a grey horse with a black harness." Date 1511. Wiki Commons John White the Black Tudor Trumpeter Dr Kaufmann’s publication is another gem, presenting as it does the story of 10 separate individuals the lives of whom, colour aside, would normally be passed over. As such it covers aspects of Tudor history that are a far departure from other offerings covering a similar period. Her opening chapter focuses on John Blanke (John White) a black trumpeter who first appears in 1507 being paid his wages of eight old pence (8d) per day by Henry VII. Kaufmann has done her research, digging in other records to find comparative rates for other court ‘tumpeters’, presumably to establish whether his rate was in anyway compromised on account of his colour. Crucially, she finds not. From my diggings into accounts surrounding the Battle of Flodden in 1513, it is interesting to note that John is paid at the rate of a mounted soldier, 2d more than soldier on foot, and the soldiers, mariners and gunners that arrived at Newcastle by ship with the Lord High Admiral. It is also interesting to note that at 8d, his rate is half that of the vj Tromppett[es] ych of them at xvj d by the day [6 Trumpeters each of them at 16d by the day] detailed in E 101/56/27, the Accounts of Sir Philip Tylney in 1513, and It[e]m for the wag[es] of oon Trumpett at xvj d the day [Item for the wages of one Trumpeter at 16d the day] detailed in the ‘E36/1 The Accounts of Edward Benstead’, a year earlier in 1512. At the death of Henry VII and accession of Henry VIII in 1509, John Blanke successfully petitioned the new King for a pay rise, where his wages were brought in line with those known to have accompanied the troops northwards. He married in January 1512, although to whom is not known, and the record of the gift made by the King at his wedding is the last record Kauffman has found of Blanke in the royal records in the records. He does not appear amongst the next list of named trumpeters recorded January 1514 … could it possibly be? In all probability if Blanke had indeed accompanied the army anywhere it would have been with the King to France, rather than with the Earl of Surrey to a soggy field in Northumberland! Sir Pedro Negro and Lady Marion Hume in 1548/9 Indulging in some highly scientific research of my own within the State Papers Online i.e. entering the search term ‘negro’, returned a further interesting reference to an individual with connections to the Border region. This time it refers to a Spanish mercenary in the employ of Henry VIII during cross border hostilities known as the Rough Wooing (1543 – 1551) by the name of Sir Pedro/Petro Negro. Dr Kauffman again picks up the trail and eloquently debates the question of the colour of his skin in an online article on her website. The evidence she finds in favour of his having been black is contained in ‘a letter written in 1549 by Marion, Lady Home’ widow of George, 4th Lord Home of Hume Castle. … she is complaining about the villainy of the English who ‘dystrow all this cuntre’. Strangely it seems the Spaniards, and ‘the Mour’ behave better, ‘lyk noble men’. They owe money to the ‘pur wyfis in this toun for ther expenssis’. It seems then, that the English and Spanish, who had been at Haddington, passed through Hume on 19 March, and were billeted there, leaving debts. Yet, Lady Hume seems to show special favour to the Spaniards, and especially the Moor, urging Guise to be ‘gud prenssis’ to them. Perhaps her favour was won the year before, when the Spaniards were involved in a failed attempt to take Hume castle from the English. 'Egyptians' in Northumberland and the Scottish BordersWhilst this does indeed makes fascinating reading, it is important not to lose sight of another group of people who became synonymous with Northumberland and the Scottish Borders – the ‘Eygptians’ more commonly known simply as ‘gypsies’ and often referred to locally as ‘muggers’ (potters, rather than pick-pockets!). Whilst they make only the briefest appearance here they too were known to have been in the area during the early 16th century. The first undoubted record referring to Gypsies in Great Britain is :—' 1505, April 22. Item to the Egyptianis be the Kingis command, vij lib.' "[5] This extract is a quote from the Account of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland during the reign of James IV. By the mid-19th century there seems to have been some debate over their ethnic origins, colour of their skin and other and other traits. The special opinion of him as an Egyptian, or one of a different breed from the other inhabitants of this and, must be established; and this proceeding on those noted and peculiar circumstances of manner and appearance by which, in all countries that they have visited, this loose and lazy race have so remarkably been distinguished. Among these are the black eye and swarthy complexion ; a peculiar language or gibberish, intelligible only to themselves …[6] There are many other such descriptions intermingled with evidence in equal measure that some ‘gypsy’ families were both fair haired and fair skinned. The Borders aside, records of gypsies in Scotland date back as far as 1462 with ‘Saracens’ noted in Galloway, with some sources attributing them as the origin of the traditional Morris or ‘Moorish’ Dancing. Although written over 100 years ago David MacRitchie’s book ‘Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts’ makes interesting reading and provides an alternative account to those of the English Tudor Court. Useful Links [1] Significant Scots, Andrew Barton, Electric Scotland

https://electricscotland.com/history/other/barton_andrew.htm [2] Historic Environment Scotland, Edinburgh Castle Research, The Medieval Documents, 2018 [3] Historic Environment Scotland, Edinburgh Castle Research, The Medieval Documents, 2018 [4] Miranda Kauffman http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/pedro-negro.html [5] David MacRitchie, Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts, Edinburgh, 1894. https://electricscotland.com/history/gipsies/scottishgypsies2.pdf [6] Hume's Commentaries on the Law of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1844, vol. i. pp. 474, 475. https://electricscotland.com/history/gipsies/scottishgypsies2.pdf page 2. For those of you who like digging about in old manuscripts but can't access the State Papers Online, a fabulous website The Tudor Chamber Books of Henry VII and Henry VIII containing transcriptions of manuscripts dating from 1485 - 1521 is available online at: www.tudorchamberbooks.org/ Throughout history different tiers of administrative bodies have evolved into the present administrative system – right from our local parish councils to central government. As these systems evolved, the powers they held changed too, some were lost, some were gained, and many became merged with others. At various points through history these administrative systems even governed our ancestors’ ability and freedom to move from one place to another. Where they have survived, the records created surrounding the movement of ‘people’ not only tell a fascinating story but can help us track the physical journeys made by our own ancestors in order to live and work.

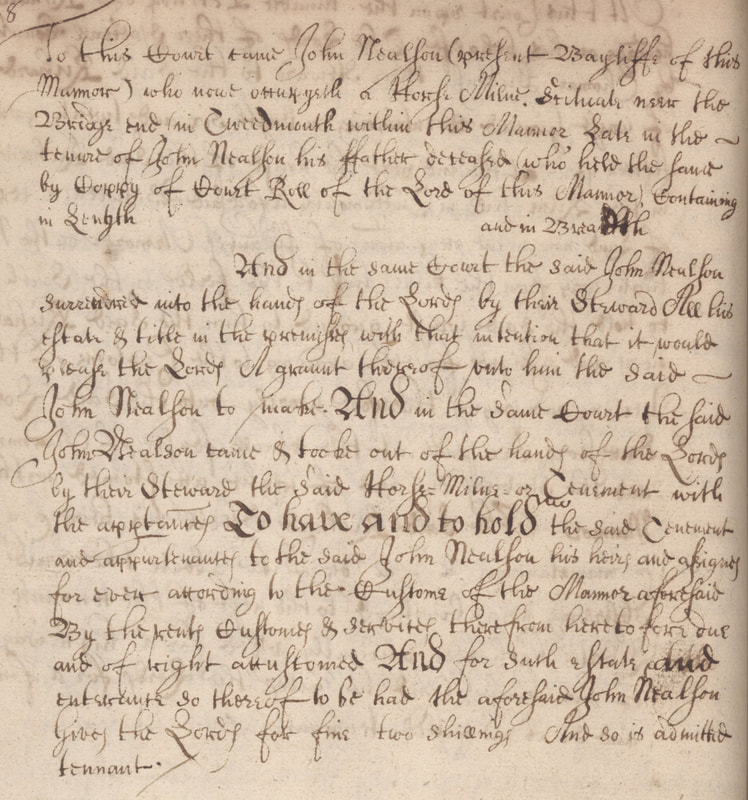

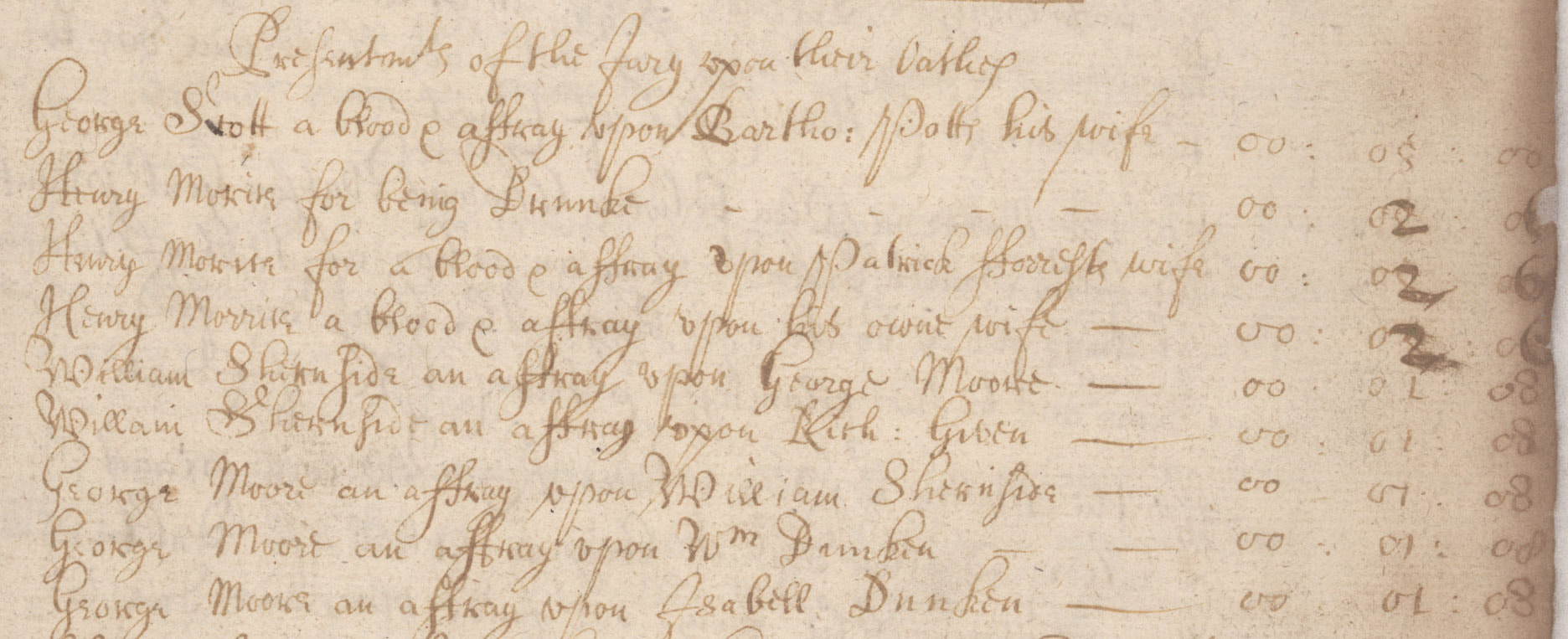

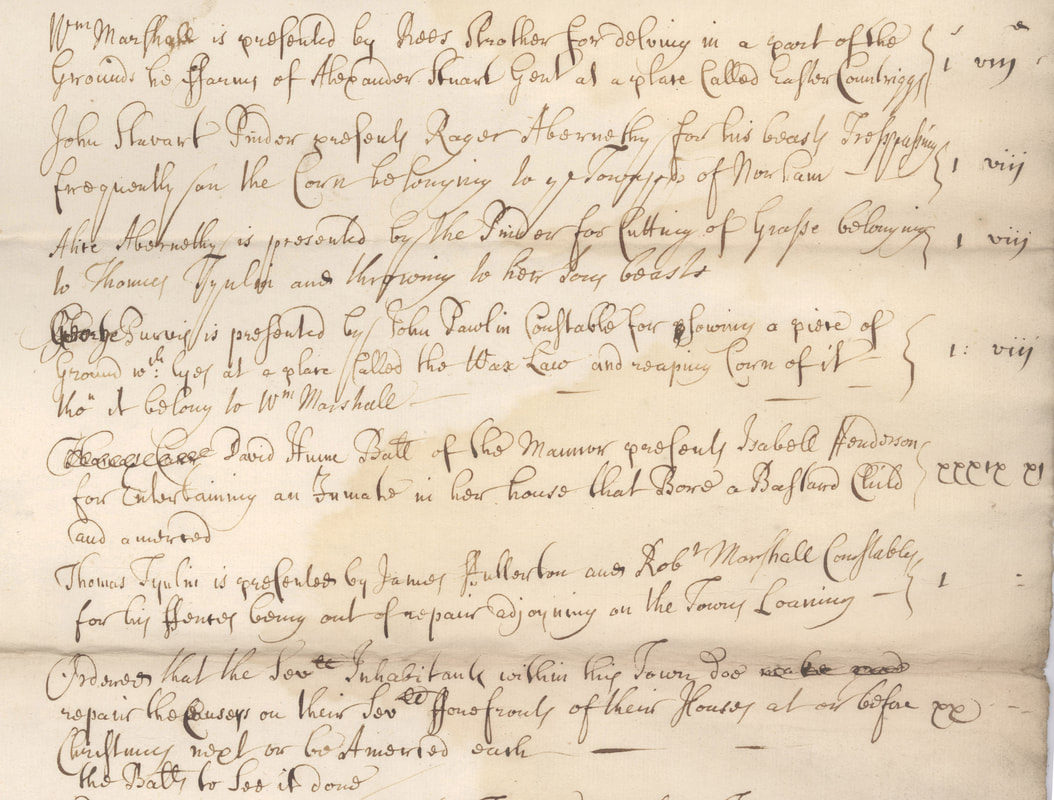

How often do I hear the phrase ‘they came from’ only to find with a bit of digging ‘they come from’ somewhere else beforehand! In truth the phrase is most usually associated with the furthest point in history reached by a specific line in a family tree, but how accurate actually is it? As with so many other things in life, the ability to move ‘freely’ and at will was the reserve of the wealthier in society. It is the poorer sections of the populace, however, whose stories are often the most interesting and plentiful amongst the records found in public archives. Movement as a Manorial Tenant - SerfdomOne of the earliest administrative units for which written records survive was the Manor. Back in March I looked at Manorial Records, what they are, and how they can help with local and ancestral research. There was, however, another aspect to the structure and customs of the Medieval Manor that was not discussed and which affected the freedom of movement for some sections of Manorial society. Within the Medieval Manorial system there existed a social hierarchy of Free and Unfree Tenants. In return for his protection, the Manor Lord would expect payment, either in cash or in kind in the form of service. For some Unfree tenants this service saw them tied to the land as Serfs. Free tenants held their lands in exchange for a monetary payment with an obligation to attend the Manor Court. Other obligations were also sometimes attached, but these were dropped and phased out over time. Essentially, although their holdings were held in perpetuity, they enjoyed a large degree of independence and were free to sell and move elsewhere if they chose to do so. Unfree tenants on the other hand, also known as villeins, bondsmen or by other local names, were subject to much more stringent conditions. They too paid a monetary rent, but in addition provided labour to cultivate the Lord’s own land known as the Demesne, carry out repairs, or perform other services necessary to the running of the Manor on which they lived. Crucially, in order to move or live away from the Manor, unfree tenants required their Manor Lord’s permission. Within this band of unfree tenants also existed the ‘Serf’ who enjoyed even less rights over their land, were essentially ‘owned’ by the Manor and were personally ‘unfree’. Whilst this might sound like a form of slavery, serfs could not be bought and sold as chattels but rather were attached to the land and Manor on which they lived. If the land was sold the serfs remained in situ and appear to have been included in the sale. Northumberland Archives features a fascinating article on its website relating to Serfdom based records relating to local Northumbrian Manors. The records contain evidence of individuals required to prove their status as ‘free men’, men earning their ‘freedom’ and of a serf’s possessions passing to the Lord of the Manor at their death. Serfdom was not purely about the work that was done, and different levies and requirements the serfs paid can be found in different manors. In many cases the lord of the manor held the right to receive a serf’s possessions after their death. This could be waived in some cases, as Theobald allowed Adam Donnesheued’s widow and daughter to remove his goods and chattels out of the manor, to his loss of 68 shillings. Some serfs tried to escape. In 1445-6 The prior of Lindisfarne received the goods of Robert Atkynson of Fenham manor after his death, but their accounts also refer to expenses in arresting bringing back John Atkynson of Fenham, Robert’s son, a native ‘meditating flight’. He didn’t run away after this, as in 1453-4 John Atkynson of Fenham, a native of the prior of Lindisfarne paid five shillings in for the merchet of his daughter Mariot.[2] As time passed Unfree tenants became known by the ‘Customary Tenants’ as lands were held according to the Customs of the Manor. The leases known as ‘Copyholds’ were more flexible in terms of conditions as to inheritance and did not attract the former levels of feudal servitude and terms of residency. (The Law of Property Act 1925, extinguished the last of the Manorial Copyhold tenancies which had not already been converted to Freeholds during the 19th century.) Whilst many of us will find evidence of our ancestors within Manorial records, in reality, it is unlikely they will fall within a timeframe to include serfs and serfdom. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating glimpse at how basic rights to move from one place to another was determined and curtailed by a social hierarchy within an ancient administrative system. Settlement & Removal Another form of local governance, which oversaw the free movement of people was the ‘Poor Law’. During certain periods, movement to other areas was necessary for obtaining work etc. Acts of Parliament introduced legislation which defined an individual’s ‘place of settlement’ or where someone belonged and the ability to be ‘removed’ back there should unemployment or destitution strike. Although containing notable differences, the basic principles of ‘Settlement and Removal’ was similar in both England and Scotland. For the purposes of this blog, the legislation and policies referred to, have been drawn from the English system. The intention being to discuss the implications of movement restrictions and the records it generated rather than the finer points of the Poor Law in either Country. Prior to the Reform Act of 1834 the administration of ‘Poor Relief’ was overseen by the Parish. (In Scotland, the Poor Law was reformed in 1845). In England, the first Act governing the relief of the poor was passed in 1552. In Scotland it was 1572 and entitled “For punishment of strang and idle beggars, and reliefe of the pure and impotent". In England several amendments swiftly followed to include a classification of the different kinds of ‘poor’ (deserving and undeserving) (1563), compulsory collection of tax to pay for poor relief (1572) more powers to raise tax for poor relief and overseers appointed to collect it (1597) a national standard and compulsory poor rate set (1601) and finally in 1662 the first ‘Act of Settlement’ was introduced. The ‘Act of Settlement’ determined which parish would be liable to pay poor relief to an individual should they find themselves in need, based on a set of residency criteria. The Place of Settlement, or where someone ‘belonged’ was determined as a place someone had been born or had worked for a certain period of time. Crucially, the Act allowed for the removal of people back to their place of settlement should they become unemployed, failed to find work within 40 days, or, were unable to pay a rent on a property worth £10 per annum. A revised Act of Settlement passed in 1697 set out more precisely defined rules for settlement qualification:

The new Act allowed strangers to settle in a parish, so long as they could support themselves and brought a certificate proving their place of original settlement with them. These ‘Settlement Certificates’ were extremely important documents as they proved entitlement to poor relief by guaranteeing folks could return to their parish of settlement should they become destitute. Certificates were issued by a church official in the original Parish and were to be passed to the corresponding church official in the destination Parish. The officials being Church Wardens or Overseers of the Poor depending on the date of issue. Certificates that have survived, usually date from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and contain the following information:

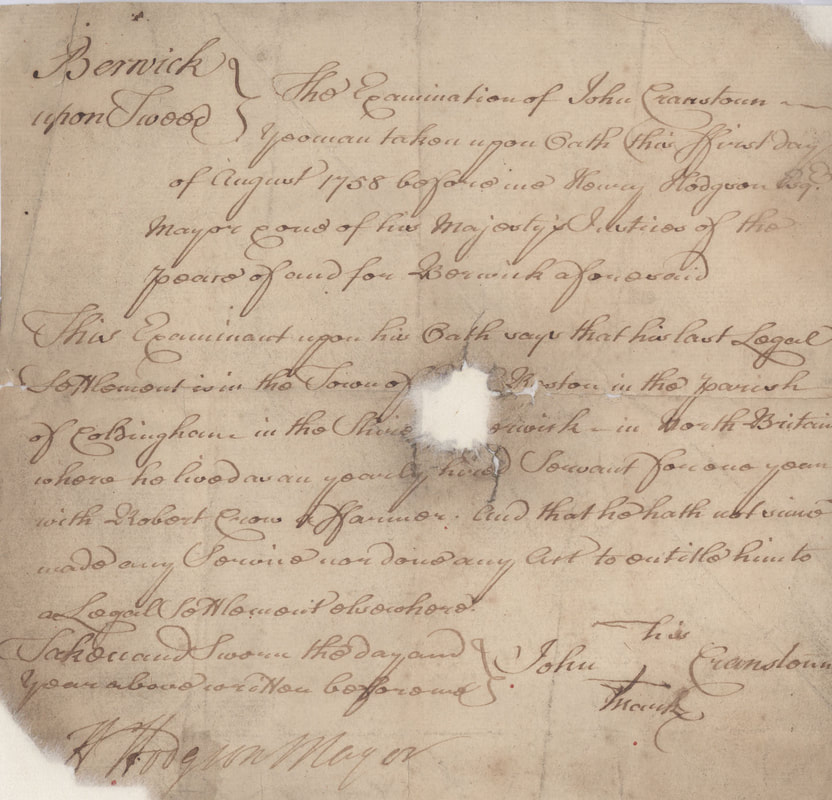

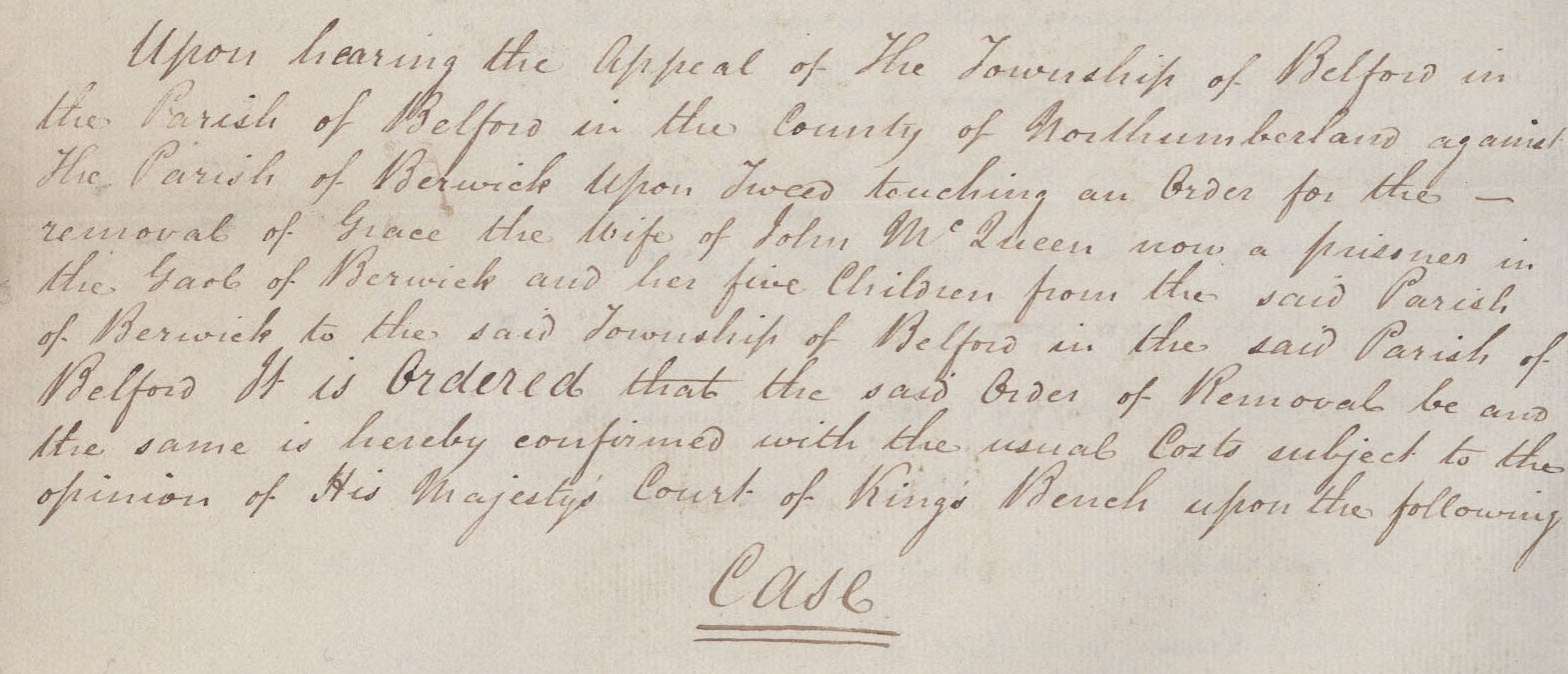

If no certificate existed and the individual became chargeable to the parish, they would be examined by the local Justice of the Peace. They would be questioned as to where they had been born, how long they had lived and worked in the parish, marital state, number of children etc. Once the place of settlement had been established a ‘Removal Order’ to the chargeable parish could be issued, along with a bill for expenses incurred by the parish where the individual or family did not ‘belong’. Removal orders would include:

It was quite common for the original parish of settlement to exercise their right to dispute a removal order. When this happened the case would go to the Quarter Sessions Court. Where they have survived amongst the court records these early examinations and removal orders can be goldmines of information. The above illustrates how the place someone belonged and their ability to move freely to live and work was historically defined by a tier of legislative administration designed to encompass the ‘care’ and governance of ‘the poor’. The freedom and ability to move was not a totally straightforward process, but did come with a theoretical safety net. Ironically it is those ancestors who required this intervention that have potentially left more evidence of their passage. The Poor Law is an extensive subject and decidedly more far reaching than the snippets concerning ‘Settlement & Removal’ briefly covered here. There are many other aspects to its administrative which can provide further rich pickings for both the family and local historian and are well worth exploring. [1] ‘Reminiscences of Thomas Marshall of Berwick by Himself’ Berwick, 1835, is available through the National Library of Scotland

https://search.nls.uk/permalink/f/sbbkgr/44NLS_ALMA21536844970004341 [2] Northumberland Archives, ‘Tied to the land – serfs from manorial history’. https://www.northumberlandarchives.com/2017/04/07/tied-to-the-land-serfs-from-manorial-history/#more-3402 The Pearcy family of ‘Glendale’ Northumberland & the value of Probate Inventories to the Family HistorianThis month I would like to introduce you to David Pearcy one of my highly valued, longstanding customers. Rather than jumping all in and selecting a one-off research and report commission, David has joined the increasing number of folks who elect to pay a manageable sum each month to uncover a new aspect of their family history in bitesize chunks. Not only does this make researching his family history more affordable, it means it is a constantly evolving story. As we all know family history is NEVER done and during this extraordinary period of restricted movement it means, in some small way, David has had a new discovery or snippet of information to look forward to each month. Rather than focusing on one particular line or individual, David is all encompassing in his approach to family history and whilst like most of us he has more questions concerning a specific individual or branch, he is looking for the whole story. Whilst always having had an active interest in his family’s history, it began in earnest following the passing of his mother and the re-discovery of her own meticulous research that contained several ancestor mysteries.

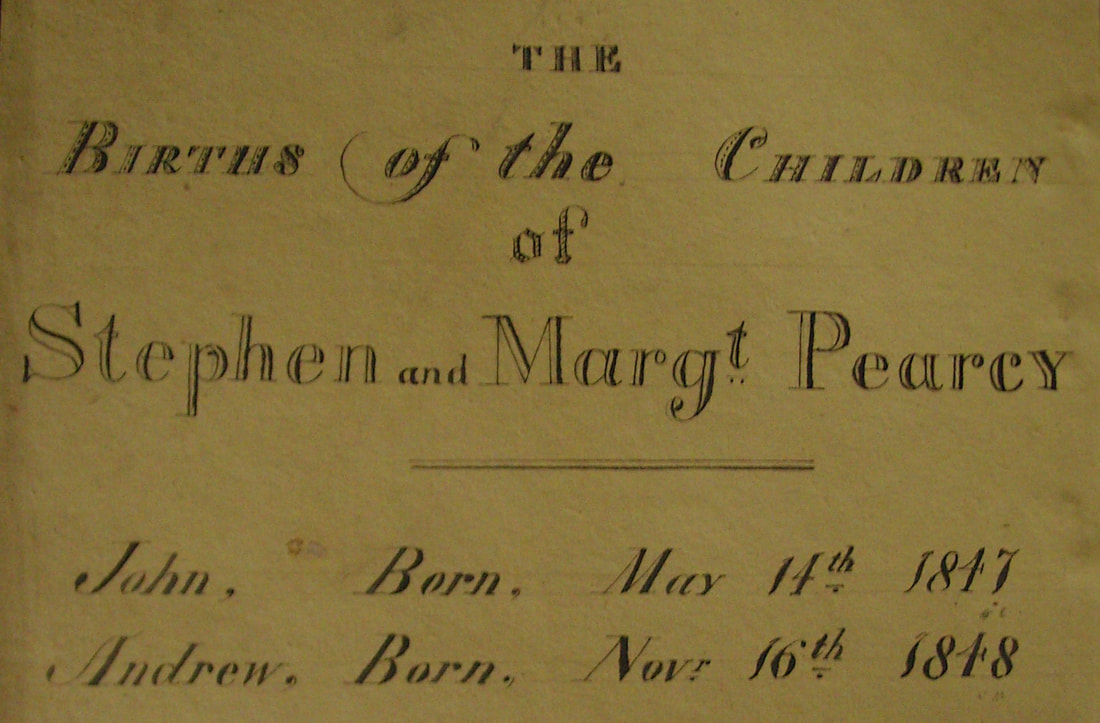

Legends abound concerning the origins of the Pearcy/Piercy family of Northumberland not to mention its wider potential connections! (A quick reminder here that the line of decent of the current incumbents of the title Duke of Northumberland although ancient has twice passed through the female line. If planning to use Y-DNA to explore links to these ‘Percys’ do please bear this in mind!) Refreshingly, David is not interested in investigating potential connections to illustrious personages but keen to delve deeper into his own historical origins – whatever they may be! Confirmed Pearcy AncestorsBy the turn of the nineteenth century David’s Pearcy ancestors were firmly established in the ‘Glendale’ area of Northumberland, and indications are that they had been for some time previous. David’s 4th great grandfather was almost certainly a John Pearcy, in this instance spelled Piercy, who died at Nesbit Buildings aged 87 in 1829 and buried at Doddington on 1st September. In 1778 John Pearcy [Percy] had married a Mary Smith on 17th May at Doddington. In August the following year David’s 3rd great grandfather ‘Roger son to John Pearcy by his wife Mary, Doddington, was born 28 August 1779’ and baptised at Wooler West Street Presbyterian Chapel on 4th September. Mary ‘wife to John Percy [sic] died at Nesbit Buildings’ aged 69 in 1819 and was buried at Doddington on 11th July. In addition to Roger, David’s 3rd great grandfather it appears the couple had a further six children, the youngest of which, ‘Gilbert son of John Pearcy and Mary his wife Doddington Greens, born 7th September’ was baptised at West Chapel, Presbyterian Chapel Wooler on 9th September 1792. This name of this youngest son may prove to be a significant key in unravelling earlier generations of the family. David’s 2nd great grandfather Stephen Pearcy who was born at Fenwick in August in 1815 became the Landlord at the Angel Inn on Wooler High Street, where he died in May 1855. After Stephen’s death his widow Mary Cock, whose family also had longstanding connections with Doddington and the ‘Cock Inn’, returned to the village and lived as housekeeper to her brother until her death at the Mill House in 1884. David has a fascinating collection of photographs and pub memorabilia dating from his family’s time at the Angel. Subsequent generations of the Pearcy family followed the path taken by so many living in the rural communities of North Northumberland who headed south to the towns where the advent of the railway and the County’s deep mines afforded employment for skilled joiners and other craft trades. His grandfather ‘Jack’ Pearcy was the last of the line to have been born at Doddington on 7th May 1885. Earlier Pearcy Family Groups The earlier generations of the Pearcy family are more challenging to unravel, not least as there are a few of them, but also by a lack of evidence to ‘glue’ them together. By the late eighteenth century, distinct family groups are evident in the areas around Norham (Horncliffe), and Ford as well as Doddington, Wooler and Kirknewton. Do these groups all descend from a common Pearcy ancestor? Naming patterns and geographic locality would suggest a degree of familial connection exists but at what genetic distance? This is just one of the questions being posed and to which David’s Y-DNA may just hold some answers.

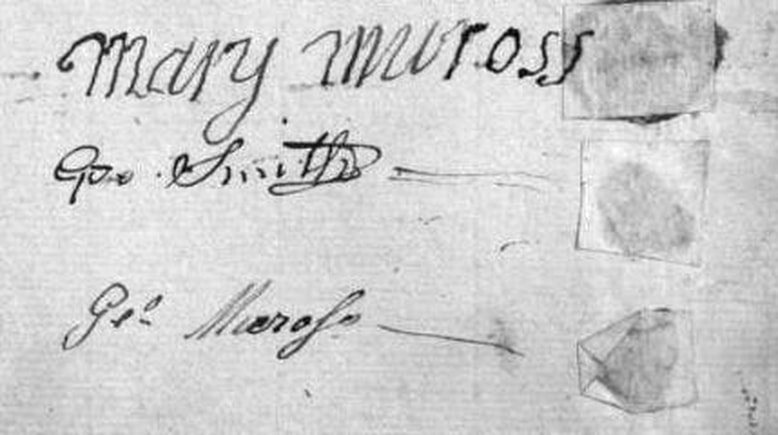

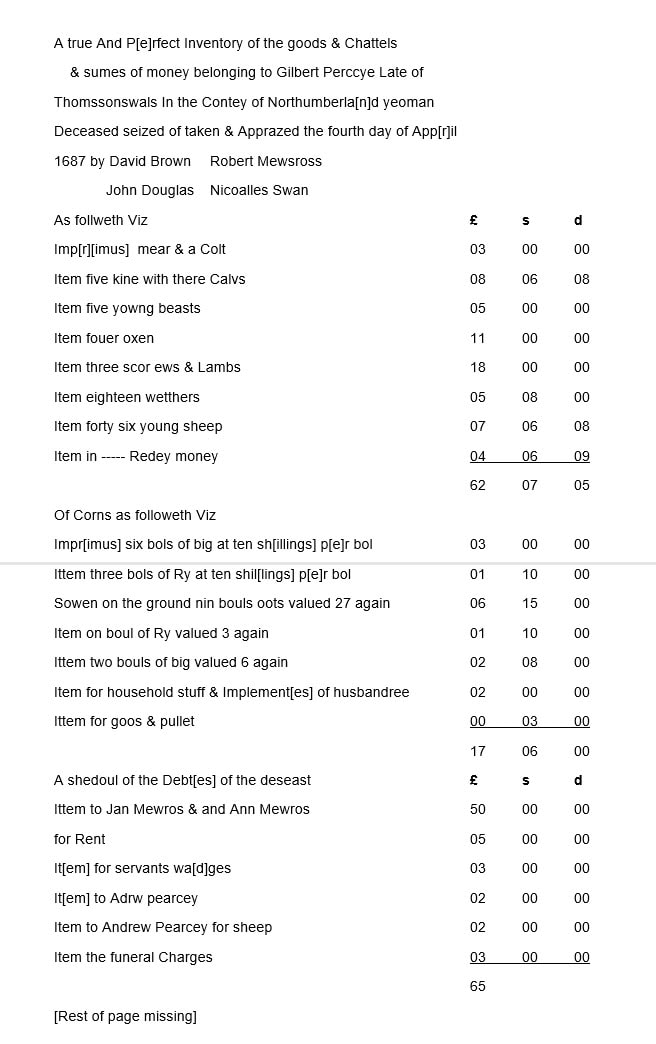

There are other potential candidates in a William Pearcy of Hazlerigg baptising children at Doddington in 1709, and a John Pearcy of Downam (Cornhill) the father of a Gilbert baptised at Carham in 1704, although from the dates these too may be from an earlier generation. Given the prevalence of the name Gilbert throughout, however, this particular family branch cannot be overlooked. It is thought highly likely that Roger, William and John were related, if not brothers, then perhaps cousins. A Gilbert Pearcy born circa 1727, calculated from the age recorded at his burial in Doddington in 1815, was likely to have been another close relative. Gilbert certainly had close ties to Doddington and appears to have been married at least twice if not three times. Inventory of Gilbert Pearcie of Thom[p]sons Walls, 1687 The discovery of an administration bond and inventory for a Gilbert Pearcie of Thomsons Walls near Kirknewton dating from 1687 is therefore potentially relevant to the investigation. Where they have survived, Inventories are veritable gems of information and tell us so much about farm livestock levels and land use, in this case of an upland and semi-upland farm during the relevant period.[1] As some folks will know this is another interest of mine, especially its capabilities and limitations of feeding an army, as in 1513. This single page of text does not disappoint. Sadly, the admin bond itself is unavailable online or to order which is unfortunate but as admin bonds are generally of limited genealogical value, not a disaster. Due to the nature of many of the pre 1695 Will Bonds it cannot be photocopied and is only available to view on site. However, as the inventory contains an amount owed for sheep, it would perhaps suggest that a relative, brother, cousin, son or nephew named Andrew Pearcy was also farming in the vicinity. Although not as distinctive a name as Gilbert, Andrew also features in David’s line of decent, indeed it was the Christian name of his Great Grandfather who was born at the Angel Inn at Wooler the 16th November 1848. Inventory of Thomas Mewres of Thom[p]sons Walls, 1683 Interestingly, the 1683 Inventory of Thomas Mewres also of Thomsons Walls is also available online. It would appear he was possibly farming a larger area and carrying more stock. It also shows a figure for £50, an equivalent of £5722.49 as at 2017 was owing to the deceased although it does not state by whom. [2] Is it perhaps the opposite entry to the debt which appears, and was still owing by Gilbert Pearcy in 1687? It is interesting to note that whilst the probate valuation undertaken in April 1687 for Gilbert Pearcy includes a figure for crops in the ground, the valuation of October 1683 does not. Does this suggest that if autumn sowing formed part of the arable rotation it was yet to take place? The autumn valuation for Thomas Mewres in 1683 with its larger quantities of Oats, Rye and Barley in store would suggest it was perhaps immediately post-harvest? There is a total absence of Wheat, which due to the nature of the land is to be expected. It was also noted that this autumn valuation contained large quantities of cheese and butter. Before the seventeenth century, cheese was largely made from ewe’s milk but by the time the probate was drafted it is thought the cheese would have been made from the milk from the five cows with calves at foot. It is glimpses into the past like these that shed light on the staple foods that formed part of our ancestors’ diets. Although not included here there are two further inventories and associated documents relating to the Mewres [Mures] family of Thom[p]sons Walls. A George Mures dating from 1694, a Robert Mures from 1710 which also includes a Will. He appears to have died unmarried and without issue as several nephews as nieces are named as beneficiaries. A jump to Lowick and a George Muross [sic] sees my own 4th great grandfather George Smith of Horncliffe standing as administration guarantor. If interested these can be found in the North East Inheritance Database Clearly it has only been possible to cover a small fraction of Pearcy research and associated evidence in just one blog. The little snippets included here are designed to ‘pique’ the interest, illustrate the longevity of the Glendale connection and provide some general historical interest for non-Pearcy readers. Should your interest lie with the extended Pearcy pedigree, however, several lines of decent have to date been traced and followed to Howick, Alnwick and beyond. The more folks that come forward with their own personal snippets of family knowledge and the more Pearcy/Piercy men that test their DNA, the more evidence will become available and meaningful conclusions can be drawn over time. If this is you, or is of interest to you, then please do get in touch with us! Notes to the Inventory transcriptions. Whilst the spellings are typically erratic, most of the language in the Inventories will be familiar, however, definitions have been provided for the more obscure words below: Bigg OED online. A hardy variety of barley grown mainly in northern England and Scotland. Cf. bere n.1. Now considered to be one of the cultivated varieties of Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare, this type of barley was previously known as H. tetrastichum because it appears to have four rows of grains in the ear. barley-bigg, Scotch bigg: see the first elements. Hoges/Hoggs 'Hoges' here have been taken to mean sheep in their 2nd year of life. Weather A Wether/Weather/Wedder is a castrated male sheep. Boll OED Online. A measure of capacity for grain, etc., used in Scotland and the north of England, containing in Scotland generally 6 imperial bushels, but in the north of England varying locally from the ‘old boll’ of 6 bushels to the ‘new boll’ of 2 bushels. Also a measure of weight, containing for flour 10 stone (= 140 pounds). (A very full table of its local values is given in Old Country & Farming Words (E.D.S. 1880) p. 168). (NB. At the time of Flodden in 1513 there were 8 bushels of corn to the Quarter and 4 Quarters to the ton.) Useful Links[1] The publications of the Surtees Society are always worth consulting when looking for collections of early Wills & Inventories. Some, such as, Wills and inventories illustrative of the history, manners, language, statistics, &c., of the northern counties of England, from the eleventh century downwards, are available online

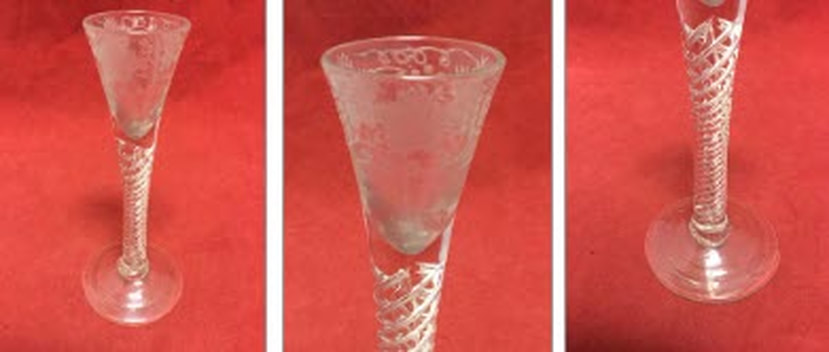

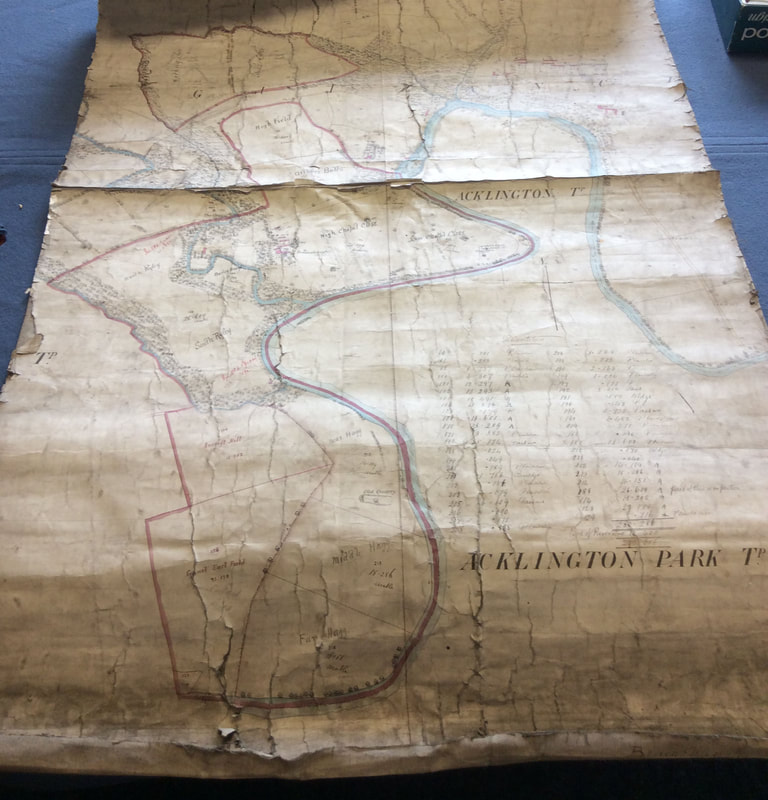

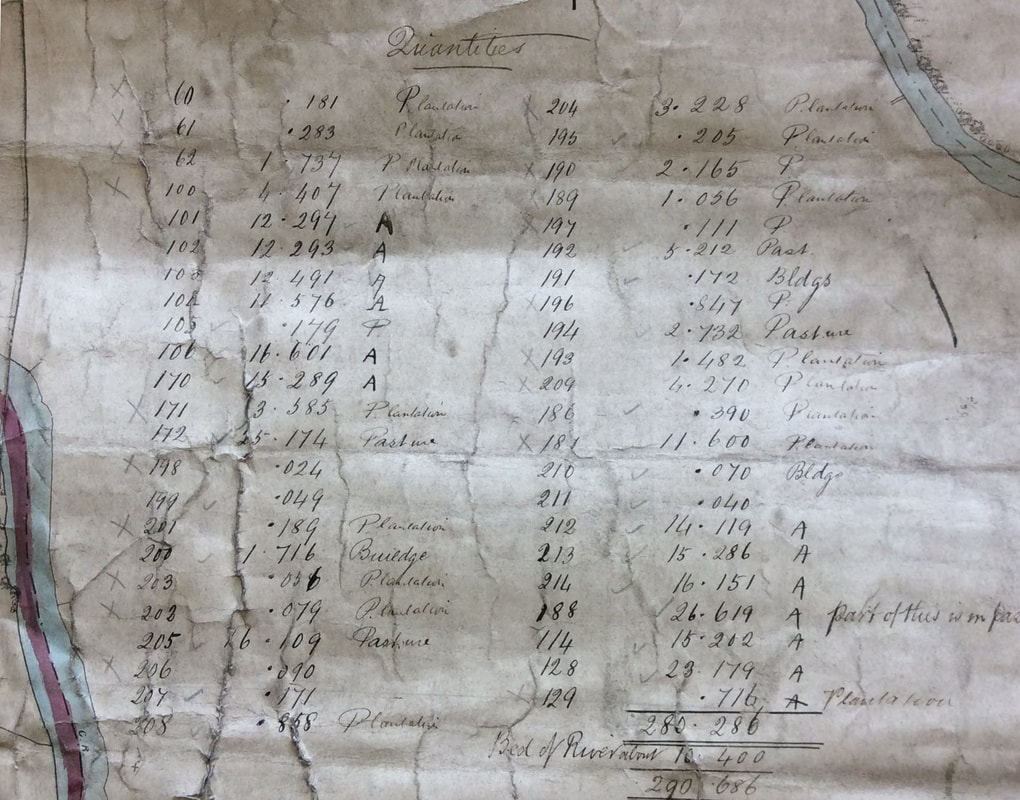

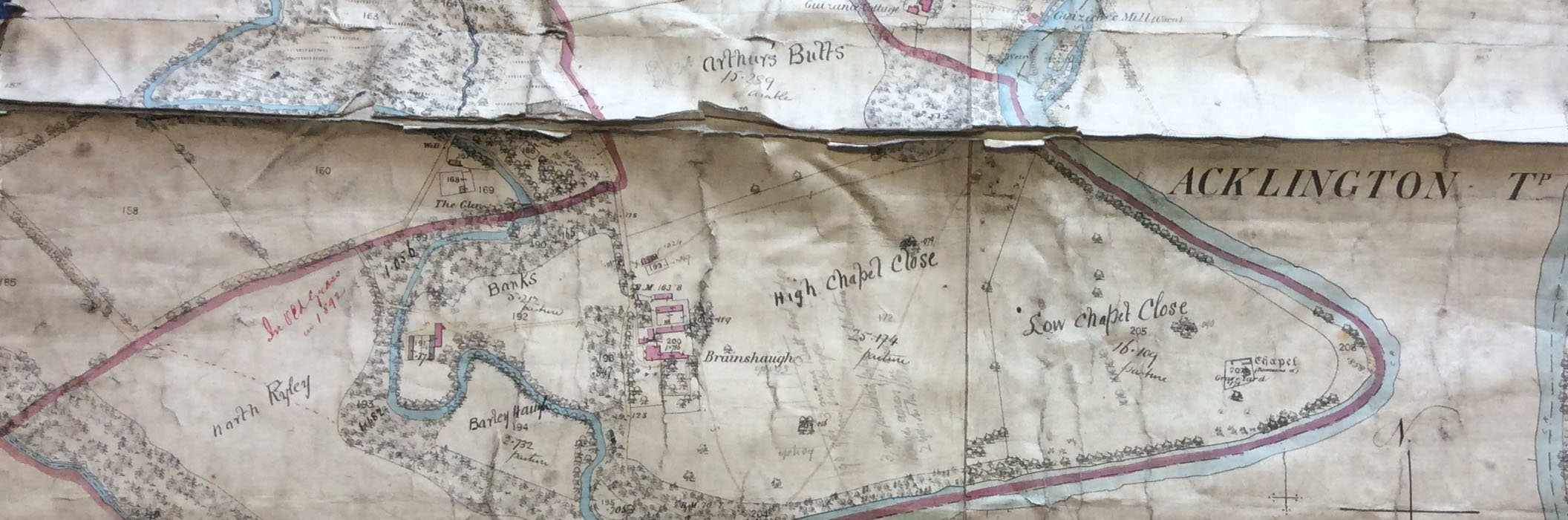

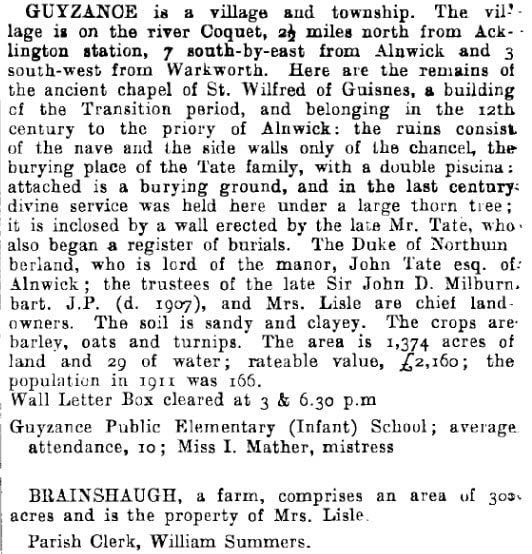

http://www.surteessociety.org.uk/ [2] National Archives, Currency Convertor https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter For the remainder of 2020 the monthly auctions at Railton’s saleroom in Wooler are set to be ‘double headers’ held over 2 days. The forthcoming sale on 18th & 19th of July is once again packed full of historical treasures, each with a unique story to tell. From beautifully delicate 18th century glasses with air twisted stems, to pewter tea sets that serve as reminders of a bygone occupation at its zenith in the late 17th century. Early Inventories for inheritance and tax purposes invariably mention pewter plates and utensils too, so keep an eye open the next time you are delving into the records. For two centuries from 1474 pewter was unrivalled as a material for plates, dishes, drinking vessels and similar ware. From the 16th century the indispensable preliminary for a Freeman setting up as a Master Pewterer and opening his own shop was to record his 'touch' or trade mark on large pewter sheets retained by the Company in the Hall. The early touch plates were lost in the Great Fire; the five that survive today record the marks of Master Pewterers from then until the beginning of the 19th century when the Company no longer exercised the power to enforce this regulation. These plates provide a unique record of pewterers of the period containing over 1,000 individual marks and are of great historical value.[1] If you had a Pewterer Ancestor in the family is their individual mark amongst them? The Worshipful Company of Pewterers dates from the medieval period, with the earliest documented reference dating from 1348. The Guild ranks No 16 in the pecking order of over 100 City of London Livery Companies. The Company’s website provides some fascinating historical background as well as the role of the Company today. The Fifteen Minute ChallengeAs the current issue (August) of Family Tree Magazine features an interesting article on maps and where to find them it seems particularly fitting to focus on an item in the sale that is also cartographical in nature. Lot No 160, a nineteenth century hand-coloured map of Brainshaugh fits the bill perfectly! It is also possible to pinpoint the date of the map even further from one or two of its distinguishing features.

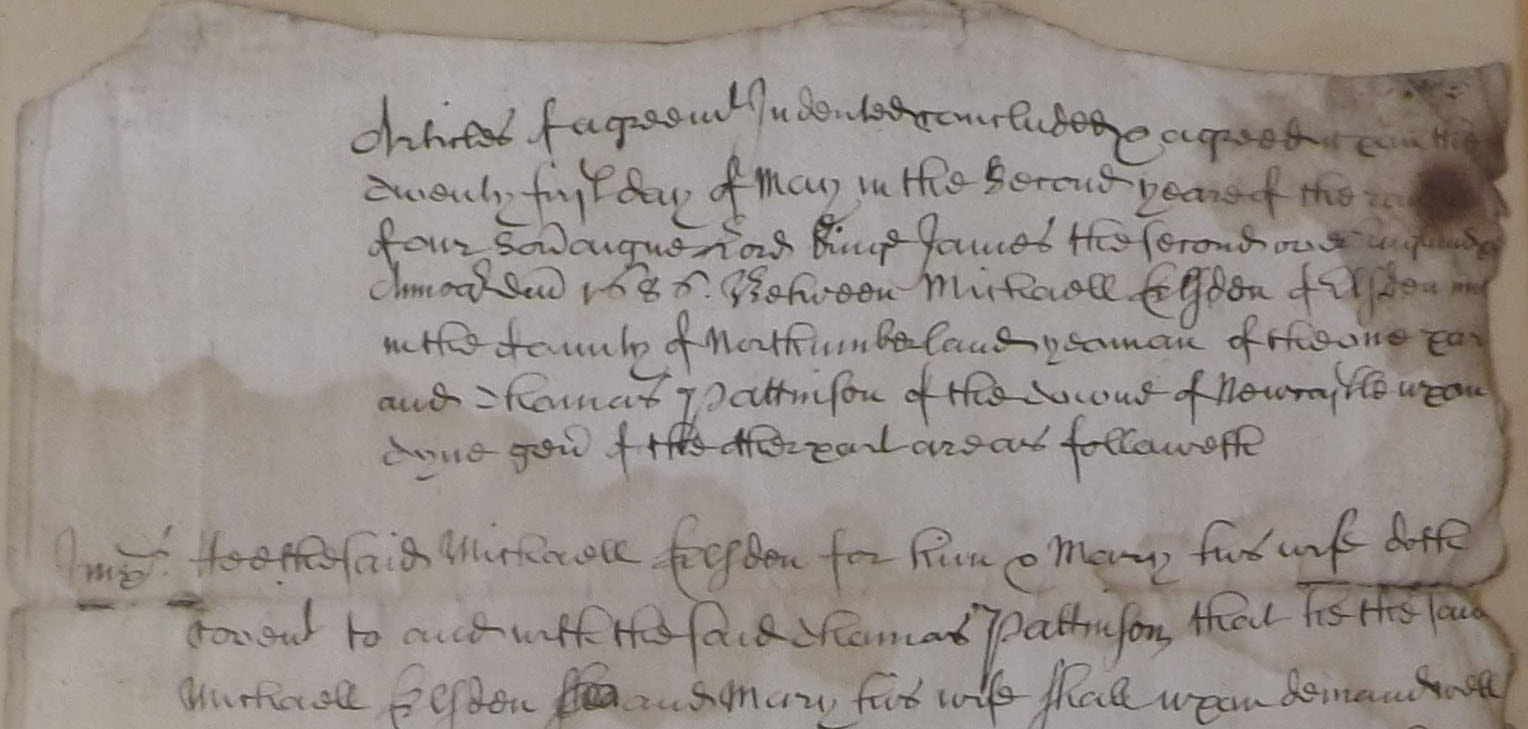

Taking the above information into account the map can now be more accurately dated to between 1854 and the mid-1880s with a good degree of certainty, possibly favouring the earlier rather than later period due to presence of handcolouring. With this in hand I set myself a challenge – how much history could I actually unearth about Brainshaugh and its people in just 15 minutes? 1. Field names of High and Low Chapel Close and the remains of an ancient Chapel and burial ground betray a former religious connection. A quick look on the Historic England Website confirms it is indeed a scheduled monument, entry number 1006579, first listed in 1932. It also contains the following information. Guyzance chapel was originally part of Guyzance, or Brainshaugh, Priory of St Wilfrid, which was founded between 1147-1152 by Richard Tison for Premonstratensian Canonesses. It is thought to have been abandoned at the time of the Black Death and later became a cell for the Premonstratensian Abbey at Alnwick. It was dissolved in 1539. So, although it had previously fallen into disuse, the ‘Dissolution of the Monasteries’ likely provided the final nail in the coffin. Not a bad starting date for the challenge of 1147! Historic England also contains a record for Brainshaugh House, list no 1153504 first registered in 1969. House. Late C16 or early C17; south front remodelled in second quarter of C18; enlarged and given new west front 1805 for Thomas Cook. Squared stone, of near-ashlar quality in 1805 parts, except for rubble of east elevation and roughly-squared stone of east part of north elevation; cut dressings. Lakeland slate roof to main block; kitchen wing with pantiles except for asbestos sheets on east end; stacks rebuilt in brick on old bases. Main block formerly L-plan, enlarged to a square in 1805; kitchen wing to south- east. 2. The North East Inheritance Database was the next port of call and provided a mighty haul of inhabitants for Brainshaugh covering several centuries. 1597 Gray, Henrye Brainshaugh yeoman will, inventory 1597 Gray, Annes Brainshaugh 1672 Thompson, Arthure Brainshaugh inventory 1678 Osmonderley, Mary Brainshaugh will, inventory, bond 1706 Barker, Edward Brainshaugh will, wrapper, will bond 1736 Davison, Thomas Brainshaugh yeoman will, will bond 1748 Cook, William Brainshaugh gentleman will 1769 Beall, Ralph Brainshaugh yeoman will 1775 Cook, Edward Brainshaugh esquire will 1786 Tomling, Henry Brainshaugh yeoman administration bond 1792 Cook, Thomas Brainshaugh gentleman administration bond 1792 Tate, Margaret Brainshaugh administration bond 1814, 1815 Graham, Richard Brainshaugh farmer will, will bond 1786, 1824 Tomlin, Henry Brainshaugh yeoman court docs/admin bond 1826 Robson, George Brainshaugh farmer will 1832 Tate, John Brainshaugh esquire will 1834 Garrett, Benjamin Brainshaugh husbandman will 1835 Grey, John Brainshaugh husbandman will, codicil 1837 Tate, Maria Brainshaugh will 1841 Bell, William Brainshaugh farmer will, affidavit 1843 Tate, John Brainshaugh esquire administration bond 1856 Bolam, Robert Brainshaugh farmer will, wrapper The earliest entry of 1597 looks most interesting: Henrye GRAY, husband of Annes Gray, yeoman, of Gisons (Guysone, Gyasings) within the parishe of Brainshaughe within the countye of Northumberlande [Brainshaugh, Northumberland]; also spelt Graye Date of probate: 1597 The inventory includes the debts of Gray's wife, and was apprised upon her death: among the debts is a fee Gray's widow charged for cleansing the house after the plague, and with which disease it is likely Henrye Gray was infected when he died.

So it is now known the plague visited Brainshaugh on at least two occasions. In terms of will makers, Brainshaugh and its immediate environs appears to have been dominated by three families, that of Grey, Cook and Tate. No doubt the Wills of these and other individuals will shed more light on fortunes of Brainshaugh through the ages. 3. Moving into the later 19th century and heading towards the present day, a search of the census using search terms ‘Brainshaugh, Northumberland’ produced a staggering number of results. Due to the 15 minute time constraint the search was refined using exact location and only the 1861 census was viewed. It returned 23 individuals. The Farm extended to 300 acres and was occupied by a Thomas Crossly from Berwick upon Tweed, Ann his Scottish born wife and 10 other members of their family, largely born in Berwick or Scotland with only youngest daughter aged 2 born at Brainshaugh suggesting the move there to have been relatively recent. There were two further households at Brainshaugh, one, very possibly Brainshaugh House, consisting of three individuals, two named Mitcheson, a retired Merchant and his wife, and the third occupant their nephew by the name of Carss. The second household contained Thomas Dickson an Agricultural Labourer and eight members of his family, the youngest of which was likewise the only child to have been born at Guyzance. Like the Farm House, the occupants of the two other properties were born in Scotland, Berwick upon Tweed or other parishes in north Northumberland, which may indicate they all came to Brainshaugh as a ‘job lot’. Further research may even reveal a degree of relatedness perhaps? 4. For Trade Directories a quick search of Kelly’s Directory for Northumberland for the year 1914 returned the following: This entry suggests the farm had not changed in size from the time of the 1861 census, but is slightly more that the hand written schedule on the map up for sale which totals 290.686 acres. (Note to self – a church service under a thorn tree sounds decidedly parky in winter. It is hoped the vicar kept the sermon brief for the comfort of his congregation!) 5. Moving forward to 1939 and the outbreak of WW2. Sadly an exact search of the 1939 Register returned a nil result and returns for within a 5 mile radius were too numerous to search in the allotted time. 6. An exact search of parish records using the term ‘Brainshaugh, Northumberland’ returned 47 results; 44 marriages, 2 death duty entries, including Maria Tate nee Bell whose Will is listed above, and one notice of a Death at Sea from Typhoid in WW2 for 17 year old Morris Gordon Robertson. A quick Google returned the following for 1945, when 10 18 year old soldiers were tragically swept to their deaths in the River Coquet whilst on exercise. https://www.northumberlandarchives.com/2016/09/13/a-tragedy/

[1] The Worshipful Company of Pewterers