IntroductionContrary to popular belief I have many interests besides ancestral research! One of which was instrumental in leading me to the subject of this month’s blog, and that is the promotion of unsigned music! Borders Ancestry currently sponsors the live shows on digital radio station EGH Radio, broadcast from 9.00pm - 10.30pm every Monday & Wednesday night. It was David Mossman, the father of Monday’s Rock Show host Anne Jobling that posed this question last summer. “Ask your woman what she knows about Biteabout Colliery and my grandfather David Brown who fell down the pit”. Well I have to confess at the time of asking I hadn’t actually heard of “Biteabout” Colliery but figured that it must have been one of the numerous drift mines that littered the area of North Northumberland West from Berwick to Cornhill and South to Eglingham, in their heyday during the 19th century. As I was to find out there is quite a bit about “Biteabout”!, so this blog is dedicated to you David. I hope you enjoy the discoveries I made when I went digging for your family, and the connections with coal mining in the area around Lowick.

The Mossman Miners My research began by drawing up a basic family tree linking David Mossman back to David Brown. Mr Mossman’s father (also David) had himself been born in the Lowick area, at Doddington in 1904. The David mentioned in the paragraph below is Mr Mossman’s father. By the beginning of the 20th century many of the smaller mines in North Northumberland became unviable and began to close. Mining families moved south to the larger collieries of Mid and South Northumberland, or further to the coalfields of Tyne & Wear and Durham. By the time of the 1911 census, John Mossman and his family were living at 43 Hedgehope Tce, Drift, Acklington in Northumberland. David’s older brother Robert John now aged 15 was already working below ground. David was the fourth child and the second son of John Mossman and his wife Barbara Ellen Brown. The Brown connection now potentially established I was interested to follow the Mossman line back a bit further to see where it would lead. John Mossman’s occupation was a Coal Miner. He was born in Lowick in 1873, the son of - Robert Mossman b. 5th January 1837 in Ford, Northumberland, occupation Coal Miner son of - John Mossman b. Grindon Ridge (Rigg) Norham, baptised Etal Presbytery 1808, occupation Coal Miner son of – John & Sarah Mossman of Grindon Ridge (Rigg) Tracing the Brown Family

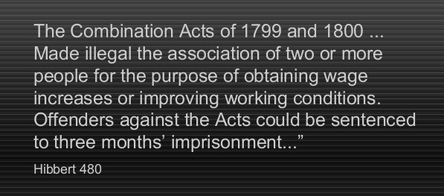

Mining in North Northumberland in the early 19th Century – Strike of 1820Strikes by Mineres were recorded as early as 1765, and didn’t go unnoticed. The British Government fearing revolution and social dissatisfaction amongst the disadvantaged masses passed the “Combination Acts” in 1799 outlawing public meetings and the formation of unions, effectively rendering potential strike action a criminal offence. Much unrest was brewing both above ground within Agriculture labour force, and below amongst the coal miners. Essentially it had the same root cause - the contract and means by which they were employed on an annual basis (known as the “bond” or “binding”) and the rates and methods of payment. The Industrial Revolution that had begun in the 18th century was powered by steam and people. The requirement for food and fuel was soaring, and the demand was being met by a workforce rendered little more than slaves under the terms of their “bond”.

Stocks of coal had run out and high winds had prevented the landing of coal brought in from Newcastle at Berwick. When the strike finally came to end on the 18th it is estimated that no less than 70,000 inhabitants in the region had been affected. The “Combination Acts” were repealed in 1824 and the formation of Trade Unions was now legalised. The Rise & Fall of the Early UnionsThere can be no doubt that David Brown would have been involved in this dispute. At 16 years of age he would already have been working in the mine for a minimum of 2 years. John Mossman being that bit younger at only 12, may not have been directly involved, but would have been all too aware of the significance of the action being taken.

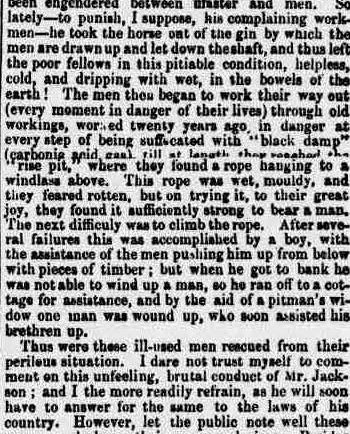

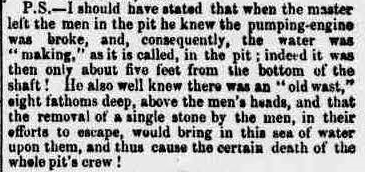

The tragedy encountered during the resulting “great” strike in 1844 was not felt as severely in the coal mines around Berwick as it was in other areas. There was only one reported case in the press of miners being evicted from their tied cottages and replaced by “black-jacks”, men from outside the region willing to work. However, the high handed approach of some coal owners was still felt by some. Unscrupulous coal owners keen to exert their authority over their workers took matters into their own hands. None more so than Henry Jackson, coal owner at the “Biteabout” Colliery. The Case of the "Biteabout" MinersWhen the miners “bound” in April 1845 heard they were not receiving the wages Henry Jackson had himself set out in writing in their contracts, they were naturally aggrieved. Mr Jackson sought to quell the unrest by removing the pony from the gin, leaving his men stranded underground. The full horror of this was reported in the newspapers:- Indications that Mr Jackson’s intentions had potentially been far worse were added in this postscript:-. When the miners reported this incident to the authorities, (amongst whose number were three respected local magistrates), it was immediately dismissed as no-one had in fact, been hurt! In due course the incident came to the attention of the Union, who mustered financial support from amongst its members. Newspaper reports throughout the ensuing months of March, April and May give regular updates on the cause, and detail the numerous pledges received to help the miners pay for the legal representation necessary to fight their case. The last report to appear in the press on the 13th June states the date set for the hearing as the 3rd of July 1846 in Ford and then ……. nothing! Nowhere can I uncover a report or account of the trial, or whether Mr Jackson received his comeuppance! More annoying still is that although the names of the protagonists are meticulously recorded, nowhere can I find the names of the affected miners. As such, alas, I have no way of knowing if David Brown was amongst them. David Brown, coal miner 1804 – 1873 & His Family

I find this a little unusual given this was the time of the “bond” or annual contract of employment. By 1851 the household now includes a nephew, James Fairbairn aged 12, who is working as a “Gin Driver”. David continued to work as a miner and in due course was joined by his all his sons barring his youngest David jnr, who was an apprenticed joiner in 1871. His eldest son William, also a coal miner had married by this time, and had moved with his family to the colliery at West Dryburn. Son Robert was also married but was living with his young family next door to his parents. Sons John, James and George as yet unmarried were living and working alongside their father, who by 1871, was now the “Overman” or manager of the Biteabout colliery. Nephew James Fairbairn who had become a permanent family addition, and also a coal miner, is now married and living next door. In 1872/73 unrest had once again begun to surface over the question of the annual “bond” . David is briefly mentioned in the press as having attended a rally in Ancroft in August 1872, and although not one of the public speakers, he heads the miners, estimated at between 200 to 300, in the discussions that followed the public address. In the 1870’s the lives of the Brown family begin a period of radical change. Son James whose occupation at the time of the 1871 census had been a coal miner was Tailor and Clothier in Alnwick at the time of his marriage to Ellen Augusta Hagar, a clergyman’s daughter, in Jedburgh on the 28th October 1873. Just eleven days later on the 8th November, father David died as the result of an accident. He had tragically fallen down a pit shaft at the Biteabout mine.

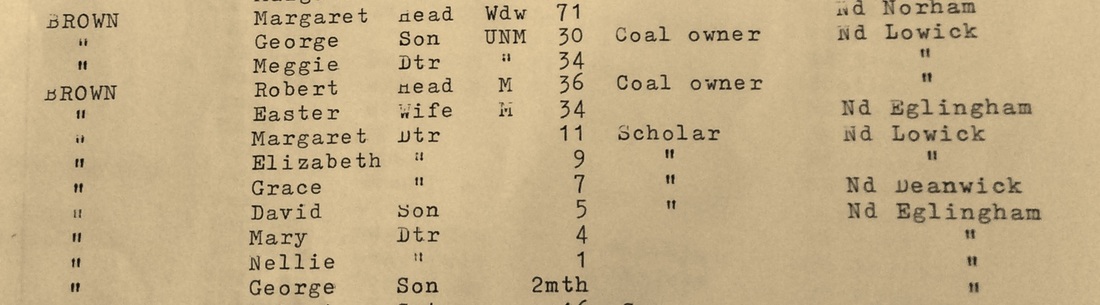

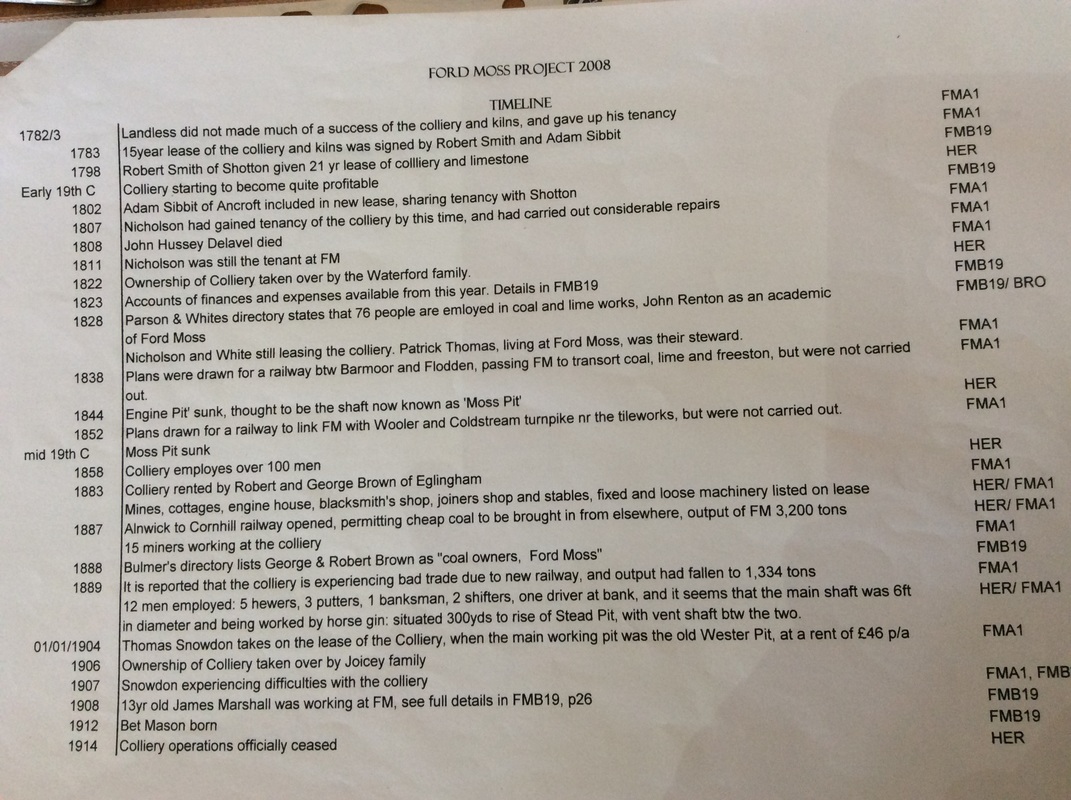

By 1901 Robert Mossman had passed away, but the family still resided at Kemping Moss, son Thomas was now the Colliery “Overman”. Son John and wife Barbara were living nearby at Doddington North Moor and he too as we know, was a coal miner. In the meantime, brothers Robert and George along with their unmarried sister Meggie and widowed mother Margaret had moved a few miles West to Ford Moss Colliery. It would appear from the baptisms of four of Robert’s children they had a brief spell living in Eglingham in the interim period from circa 1874 – 1881. The return to Ford Moss colliery in 1881 was however, not as coal miners, but as coal owners! Further delving into the records of Ford Moss Colliery reveal that brothers Robert and George remained in partnership here until 1904 when the lease passed to a Thomas Snowdon. However, by the time of the 1901 census neither brother is in residence. Robert has taken the tenancy of Colliery Farm near Chatton, and George had married and moved to Bootle, Merseyside where he was the proprietor of a grocery shop (unconfirmed). William, the eldest of the Brown brothers was last recorded in 1891 living in Ancroft and manager of the Scremerston Colliery. His sons David and George continued in the family mining tradition as did youngest brother David and his three sons John David, George and James as outlined earlier. The Fairbairns – A tragic tale with a happy ending.Intrigued to know the circumstances as to why James Fairbairn had been living with the Brown family from at least 1851, and to determine his exact relationship to them I did yet more digging. What I unearthed was a truly tragic story, but one that could so easily have been far worse. James had been born the fourth child and second son to James Fairbairn, originally a shoemaker by trade and Isabella Fish his wife. Isabella was sister to Margaret Fish the wife of David Brown. By the time of his birth, the Fairbairn family had moved to the Lamb Inn near Lowick and his two older sisters had died in infancy. A brother George was born in 1841 and in December 1844 they were joined by another brother Robert. By the time of Robert’s baptism in February 1845 their mother Isabella had died. Baby Robert was soon to follow. Infant mortality was high in those times, and mothers often perished after a difficult childbirth but what thoroughly tugged at my heartstrings was a note in the baptism register. It had probably been taken from the parish minute book and notes that “Father, mother and sons are tenants in the Lamb Inn, sleeping in the dust”. What became of the father James Fairbairn I do not know, but at least the fate of the three surviving sons was in safe hands. The eldest John born in 1834 was taken in by his grandparents John and Margaret Fish in Ford. John followed his grandfather’s profession of Boot and Shoe Maker, he married and had a family. James as we have seen grew up with the Brown family, married and had a family. The youngest of the boys George born 1841, brought up by his uncle Robert Fish and wife Ann in Ford, grew up to be a Colliery Salesman who also married and had a large family of his own. What could easily have ended like a ghastly chapter from a novel by Charles Dickens in the Parish Workhouse was averted by the kindness and support of members of the Fish family who rallied round and raised the three boys as their own. Although the boys grew up separately, they obviously remained close as can be seen in later census records. They had a tragic start in life, but with the love and support of their mother’s family they went on to lead happy and fulfilled lives. John the eldest named one of his daughters Margaret Brown Fairbairn I feel sure this was out of respect and affection for his aunt. ConclusionThis research has been a revelation to me as I have never before encountered two families of such resilience and so deeply entrenched almost without exception, in one single occupation. I quake to think how many thousands of tons of coal these families have extracted over the course of at least five generations. Especially when you take into consideration, the numerous siblings, cousins, uncles and sons who also spent the majority of their lives underground! research notesDavid Brown 1804-1873 There a host of online family trees which have attributed his parentage to a David Brown & Isobel Mossman of Tweedmouth Square and linked him to a baptism in Spittal in August 1800. I find no evidence to support this parentage for a number of reasons; The eldest son of David Brown (born 1804) is named William born 1831in Lowick. Although there was a child named David who died in infancy with no known birth or death date, if he had been the first born, he had passed away before the census in 1841 and it is unlikely the couple would have waited until the birth of their seventh son to re-use the name. Therefore if the family follows the traditional naming pattern, evident in later generations, I would expect his father’s name to be William. Secondly mother’s name Isobel. None of the children of David & Margaret carry the name Isobel and neither do ANY of the subsequent grandchildren. Thirdly in every census David is clear on his birthplace and age. The family followed the Presbyterian religion and as such were viewed by the established church as “Dissenters”. This makes research potentially more problematic as there are far fewer records. I believe what has happened in this case is that a record has been found on the internet, for a Presbyterian baptism of a David Brown in 1800 at Spittal and it has been made to fit, rather than consulting the records of the Scotch Presbyterian Church at Lowick, not available on the internet but which contain the baptismal records of several children born to a William & Margaret Brown of Lowick from 1808 to 1817. The Church register begins in 1804. There is also an irregular marriage at Coldstream Bridge in 1796 between a William Brown of Ancroft and Margaret Hume of Lowick. These records too are unproven as to a relationship, if any to David Brown born at Lickar Colliery circa 1804, but to mind at least, they seem far more likely candidates. LinksSome great info about Ford Moss, some oral history transcripts and pics of Ford Moss before Wind Turbines

http://www.berwickfriends.org.uk/history/ford-moss-colliery/ Intro to The Coal Industry in the North East http://www.englandsnortheast.co.uk/CoalMiningandRailways.html A detailed look into the 1844 Miners Strike in Northumberland & Durham http://www.durhamintime.org.uk/durham_miner/great_strike.pdf A Glossary of Terms commonly in use in the North Eastern Coalfields http://www.cmhrc.co.uk/site/literature/glossary/ This site is not the easiest to navigate, but persist & you'll be amazed at what you'll discover http://www.dmm.org.uk/lom/ My Favourite online research tool "The British Newspaper Archive" http://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/ A very special mention and my thanks also go to "Lady Waterford Hall" in Ford Village, http://www.ford-and-etal.co.uk/lady-waterford-hall Not only is it very beautiful, it is packed with information useful to researchers with ancestors from the area. A true hidden gem!

16 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy