|

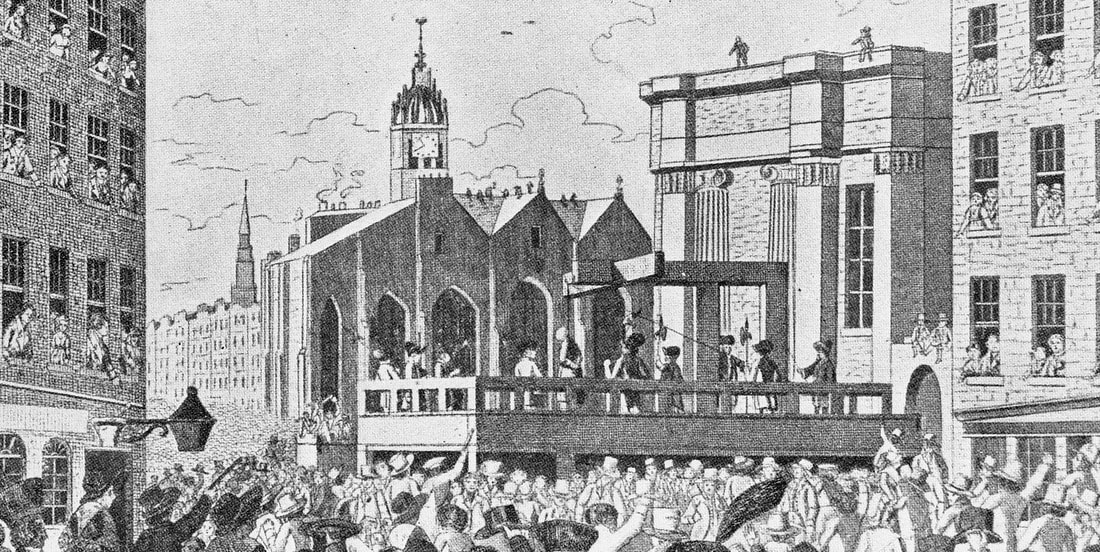

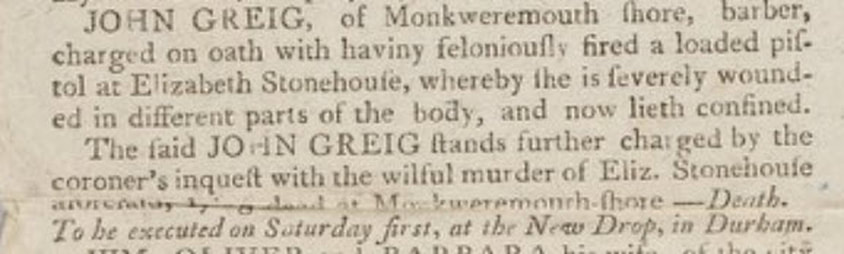

At 9.00 am on Saturday 17th August 1816, John Greig, a Barber and Publican from Monkwearmouth Shore was hanged outside Durham Courthouse. He was the first person executed at Durham using the ‘new drop’ method, where the condemned entered the afterlife via a trapdoor. He had been found guilty of the ‘wilful murder of Elizabeth Stonehouse’ at the Summer Assizes. His hearing lasted just five hours. To modern standards, five hours seems a ridiculously short duration for a trail of such gravity, but to an early nineteenth-century audience, a five-hour hearing was a long one. ‘The actual trials were often very quick; in 1833, at the Old Bailey (an Assizes court), it was estimated they averaged 8-9 minutes.’[1] Indeed, the press bemoaned the length of John’s trial as there was insufficient time to print details in the following day’s newspaper. Hence, details of the court proceedings do not appear until the following Saturday, 24th August, together with the details of his execution.

The doctor attended her at the home of Matthew Briggs shortly after the incident. As well as treating her wound, he observed a ‘large mass of disease’. Bet died on the 22nd of April 1816, some 18 days after the shooting occurred. Nevertheless, the cause of death recorded is as a result of the gunshot. This accounts for the two separate charges recorded against John in the Calendar of Prisoners for August 1816. The first for shooting and maiming, the second for her murder. A copy of the Calendar in full can be viewed online at Harvard Library Curiosity Collection It is not clear whether there was any truth in Bet’s accusations, but to date, I have found no evidence to substantiate her claims. Bet, who was born Elizabeth Parkin in 1768 does not appear to have had an easy life. Records suggest that her father Charles Parkin may have died when she was young. Aged 21, she married Samuel Stonehouse at Bishopwearmouth in January 1789. Samuel was a mariner who would spend much time at sea - he was reported to have been at sea at the time of the shooting. The couple had eight children born between the years 1789 – 1805, but only 4 survived beyond childhood. Suffering this type of loss, at times without the support of her husband must have been difficult for her. Even so, it still does not explain her accusations and why she appears to have targeted John Greig. As for John, he appears to have remained unrepentant of his actions but accepted the justice of his punishment. I suspect there is still more to this case than meets the eye. Where to start looking for records of criminal ancestors depends on the period and gravity of the crime they committed. The more serious the crime the ‘higher’ the court. Hierarchy of The Historic English CourtsThere was a hierarchy of courts dealing with crime and criminals outside of London at county, regional and national level. The judicial system and type of cases they each heard has evolved through the centuries. Until circa 1500, an annually elected Sheriff was responsible for dealing with crime and criminals at county level. Coroners who investigated sudden and violent deaths assisted him. They reported suspected murders to the Sheriff, who dealt with them through his Court. After this period the Sheriff's court dealt with civil cases only. Even so, the Sheriffs and Coroners could still ‘outlaw’ accused individuals who failed to appear at trial in a higher court. In the early modern period, Church Courts and Manor Courts also played a leading role in the trials of petty misdemeanours. These courts heard the majority of petty cases until the Restoration. The most important officers of the County judicial system were the Justices of the Peace. Drawn from the County’s landed gentry there would be several in office at any one time. Acting on their own or in pairs their ‘powers’ were far-reaching. Nowhere more so than acting as ‘judges’ over the Quarter Session Courts. Assisted by grand and petty juries, they could try more serious criminal cases. They could also determine the punishments for those convicted. Above the Quarter Session Courts were the regional Assize Courts who were answerable to the Privy Council. Local criminal cases could also be transferred to the Court of the King's Bench in London if required. The various regional courts outline above heard civil as criminal cases. They also dealt with many aspects of local administration. Below is a brief description of the courts in operation in the early nineteenth century and the types of criminal cases they heard. Petty Sessions Court These are what we know today as the Magistrates Court. Formed in the 18th century from Quarter Sessions they heard more minor cases, such as poaching, drunkenness and vagrancy. It was a court of ‘summary jurisdiction’ whereby the Justices of the Peace could decide on a sentence without the intervention of a jury. Their records are usually held by the local Records Offices. (NB. From the 19th century onwards the Petty Sessions also heard cases of illegitimacy. These cases are sometimes recorded in separate ‘Bastardy Order Books’.) Quarter Sessions Court As the name suggests, the Quarter Session courts met four times a year, in January, April, July and October in Counties and Boroughs with the right to try criminal cases. They are normally associated with a county but some boroughs and cities could also hold their own courts by a grant of royal decree or charter. Presided over by the justices of the peace and two juries, they heard more serious criminal cases. The cases heard were not usually for capital offences, but there were exceptions. ‘Before 1842 the line between Assize and Quarter Sessions cases was rather blurred; an Act of that year consigned all capital offences (those that carried the death penalty) and also cases with sentences of life imprisonment, for the first offence, to the Assizes.’[2] Some boroughs such as Berwick upon Tweed could and did, try crimes attracting the death penalty as their records will testify. As with those of the Petty Sessions, the Quarter Session records are held in local archive offices. The Assize Court Before 1972, the Assize courts were the highest regional courts in England. Their origins date from the Medieval ‘Eyre’ courts where judges sent in the King’s name from Westminster administered justice in the counties. They were traditionally held twice a year; February/March in the Spring, and July/August in the summer and operated in six ‘circuits’ of contiguous. The exception was London, the permanent home to the Assize court known as the Old Bailey. The Assize Courts typically heard capital cases that carried the death penalty and other cases too serious for trial at the Quarter Sessions. In 1815 there were no less than 215 crimes which (in theory) could attract a penalty of death. Amongst them were:

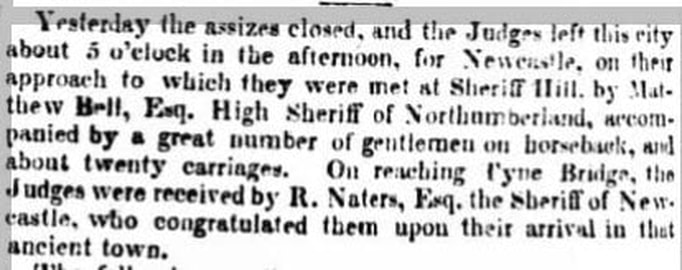

This number, sparked by social, economic and political changes had risen sharply from 50 in 1688. It was the time of what became known as the ‘Bloody Code’. Stealing 5 shillings (about £30) or being out after dark with a blackened face could result in hanging. In 1816 the two assize judges, Sir George Wood, Sir John Bayley their clerks and their retinue arrived in Durham on Saturday 10th August. Sir George Wood presided over the cases ‘for the Crown’, (the criminal cases) and Sir John Bayley dealt with matters of the Civil Court (land disputes etc.). Court proceedings commenced on Monday morning following. As at the Quarter Sessions, the Grand Jury decided which cases to present for trial. They had the power to decide which cases to dismiss, either as there was insufficient evidence or no case to answer. The Grand Jury also heard witness statements and prepared the indictments for cases being be brought before the court. If a case was to be tried, then the Petty Jury or Trial Jury was sworn in to hear it. It was they who would decide the verdict. ‘Each trial started with the clerk reading the charge again, and then the prosecutor presented the case against the defendant, followed by the witnesses, who testified under oath. Witness testimony was the most common source of evidence and Judges frequently intervened to ask questions or comment. The defendant was then asked to state his or her case. They could call witnesses, if they had any, and use a defence lawyer.’[3] The newspapers record that John Greig made no case himself in his defence but ‘called several witnesses to speak to his character, all of whom spoke highly in his favour.’ That week there were five other individuals sentenced to death. Two for stealing horses, one for stealing 3 heifers, one for killing a sheep and stealing the carcass, and one for stealing £5 in silver coin. All bar John received reprieves, most likely having their sentences transmuted to transportation. (An interesting aside is that Anne Stonehouse also appeared on the Calendar of Prisoners for the same session. Charged with ‘concealing’ the birth of a child, the Grand Jury dismissed her case before it came to trial. Whilst it is not known if any connection existed between the two Stonehouse families, it is a rather ironic twist of fate.) The assizes often lasted a week to a fortnight depending on the number of cases to be heard. Like the Quarter Sessions, the Assizes involved a lot of people and were important economic occasions for the host town. Bringing in many people, much business and money they were social highlights of the year. This extract from the Durham Country Advertiser describes the arrival of the judges and their retinue in Newcastle the following week. John Greig’s execution would have marked the culmination of the summer Assizes and associated jollities. Thousands would have gathered in what is now Durham Crown Court Gardens to watch the public spectacle. Unlike Petty Session and Quarter Session records, the National Archives holds the Assize records. A table and key to those that have survived are listed here (It should be noted that whilst Chester, Durham and Lancaster had their own assize jurisdictions, their surviving records are also held at Kew.) Documents Associated with Courts and Criminal Trials The judicial system generated various types of records, the most common are briefly outlined below:

Newspapers or other publications are another great source of information relating to a trial. (They are sometimes the only source too). Newspapers often contain an account of the proceedings of the trials themselves. A prime example of publications at work are the 'Proceedings of the Old Bailey 1674 - 1913' which are freely available online. In the case of John Greig, later articles tell of his last night in prison and collections for his widow and family. These say far more than a formal court document or testament ever could. [1] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes, http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html [2] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes, http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html [3] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html Useful Links & PublicationsOnline

Publications

0 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy