|

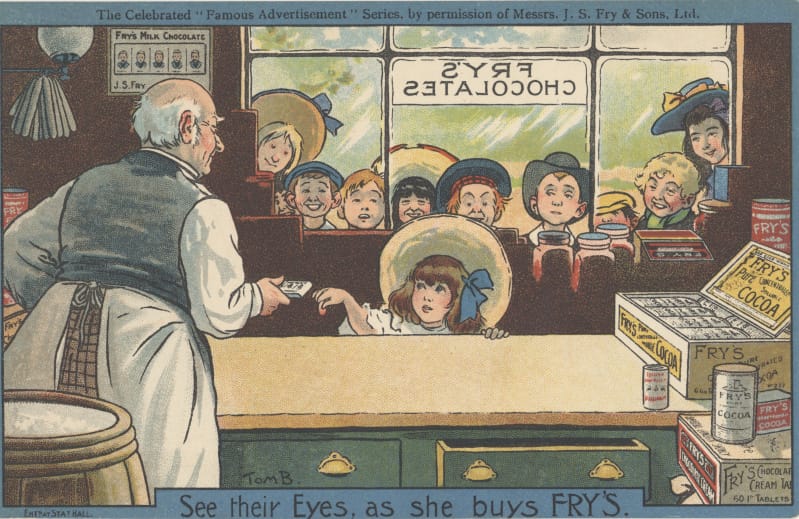

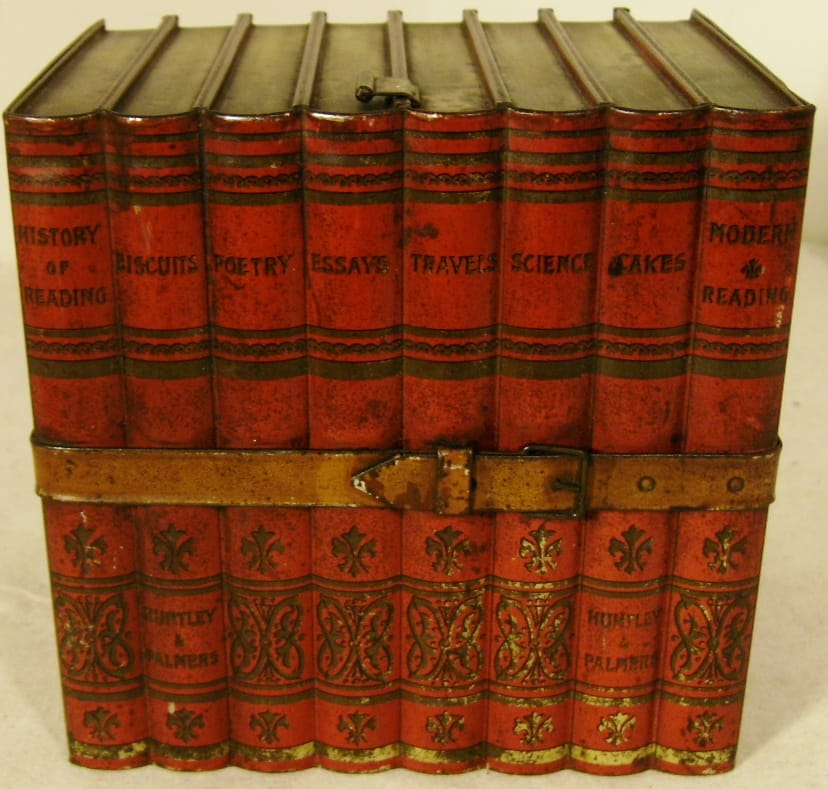

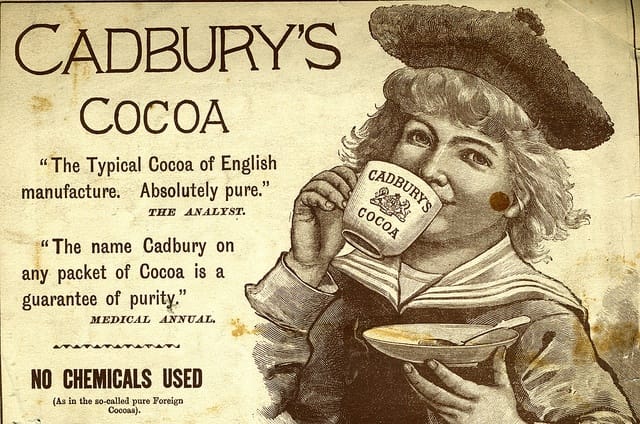

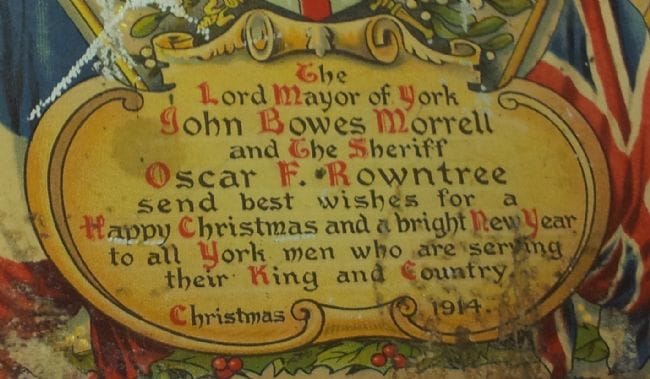

The Festive Period is a time of year that has become synonymous with ‘merry making’ and over indulgence, particularly in tasty treats. We all have our favourites and my particular weakness, along with countless others, is chocolate! For me, the darker and more bitter that chocolate is the better, and it was whilst ‘humouring’ this particular weakness I began wondering just when and how chocolate came to prominence in ‘western society’. This, and an interesting chat during #AncestryHour with renowned genealogist, historian and author Chris Paton, concerning encouraging researchers to write their family histories in factual narrative form, got me to wondering why more people didn’t do so. I daresay there are many reasons behind this relative absence, but one that sprang to mind was a lack of historical knowledge, hindering the ability to place ancestors in a social, economic and political context. A subject in which chocolate, both directly and indirectly, played an interesting role. Whilst ‘cacao’ had long been revered in pre-Christian South America as gift from their God of Wisdom, it was not until 1502 that Christopher Columbus first brought it to Europe. However, the commercial value of chocolate, then consumed as a drink did not catch on until circa 1585 when it was adopted by the Spanish Court. Its’ popularity then spread throughout Europe reaching England in around 1652. One of the first written accounts in English appears in the diary of Samuel Pepys, who in 1661, wrote of its virtues as a cure for a hangover. The popularity of chocolate spread rapidly and in Georgian London, chocolate houses sat side by side with those of coffee and tea. Coffee, it is reported had only hit the London ‘scene’ some five years previous. At the height of the Jacobite rebellion of 1715 a group of plotters were arrested whilst drinking chocolate at ‘Ozinda’s’ Chocolate House in St James’s Street, whilst a tunnel was later (1923) discovered at the ‘Cocoa Tree’ in Pall Mall by which means Jacobite conspirators could allegedly fashion their escape. Of course, as the above rather illustrates, chocolate was the preserve of those who could afford to purchase it, and although available mixed with other substances in the cheaper coffee houses of the city, it remained out of reach for the majority of the middle and lower orders of society. As such, some of chocolates’ ‘beneficial’ properties, not least it’s purported attributes as a powerful aphrodisiac, led to outcries from middle-class moralists. Thus, chocolate became associated with both luxury and decadence. With an ever increasing demand for the drink by fashionable society, the production of cocoa came under pressure. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, plantations sprang up alongside those for sugar, creating a thriving market for the ‘slave traders’. Ironically, around the same time that cocoa made it to English shores, the non-conformist religious movement gave birth, in 1649 to a group led by George Fox whose balance of ‘belief and business’ would not only become synonymous with chocolate, but also with social reform. Now known as the ‘Society of Friends’ this group are more commonly referred to as Quakers. The families of Cadbury of Birmingham, Fry's of Bristol and Rowntree's and Terrys of York monopolised the industry for more than a century and remain household names in the field of confectionary to this day. “This achievement is all the more remarkable given the tiny numbers of Quakers. In 1851 they only accounted for about one in 1,400 of the population of 21 million in England, Scotland and Wales - less than 0.1%”. But why chocolate? Quaker Historian Helen Rowlandson explains in an article for BBC Magazine: “The move into chocolate began with cocoa drinks in the 19th Century as a reaction against the perceived misery and deprivation caused by alcohol… Quakers and other non-conformists at the time were concerned about levels of alcohol misuse in the population at large, they were part of the temperance movement…Cocoa was a way of providing cheap and available drink. It was healthy because you had to boil the water to make it when they didn't have good water supplies."... (A Rowntrees Chocolate Tin from the 1920's showing Northumbrian Heroine Grace Darling. Keep your eyes peeled for her new biography coming soon from the pen of Gary Dolman.) Notable Chocolatiers: Joseph Fry (1728 – 1787) John Cadbury (1801 - 1880) Joseph Rowntree (1836 – 1925) In addition, the ‘restoration’ of 1660 may well have reinstated a monarch as the Head of State, but it was quickly followed by laws that precluded members of the non-established Church, particularly those who would not swear an oath, such as Catholics and Quakers, from positions of authority. As the Universities also had close links to the Church, and it would be 1871 before they would open their doors to other religions, this also excluded them from professions requiring a university education. Their strong pacifist beliefs also ruled Quakers out of a career in the military, so instead they turned their hands to business, in which they excelled, chocolate being but one of many. Employees of these firms which manufactured chocolate on an industrial scale were the beneficiaries of the Quaker principles of equality (including women) and social justice. “Cadbury Brothers was the first firm to introduce the Saturday half-day holiday, and also pioneered in closing the factory on bank holidays. In 1918, Cadbury Brothers established democratically elected Works Councils, one for men and one for women. Departments elected representatives to these Councils by secret ballot. The Councils dealt with working conditions, health, safety, education, training, and the social life of the workers.” Although this short piece is concerned with chocolate, other Quaker owned businesses followed the pioneering examples set by the Cadbury family with working conditions regarded as superior to many others during the Victorian period. Huntley & Palmer and Carrs biscuits, Lloyds and Barclays Banks, Bryant & May matches and Clarks Shoes are a few other easily recognised household names. Quakers, although not alone, were also amongst the pioneers for much wider social reform such as the abolition of slavery, (even though their own plantations were reliant on slave labour) as early as the 17th century. Elizabeth Fry (nee Gurney) who appears on the reverse of the English paper £5 note is famous for prison reform and helping the homeless, William Penn founder of Pennsylvania, Richard Nixon, President of the USA, and you won’t have to look far to find many others both past and present. From a family history perspective Quakers kept meticulous records, and although broadly speaking a 'Christian' religion, they do not practice baptism. However, births, marriages and deaths were recorded in the Monthly or Quarterly Meeting Books. The marriage records can be a family historian's dream, often including extensive lists of relatives and other witnesses who were present at the Wedding. Along with Jews, Quakers were exempted from Hardwicke's Marriage Act of 1753, requiring couples to marry in the parish church, which makes them unlikely candidates for 'irregular' marriage. Quakers do not celebrate Christmas and Easter as religious festivals, prefering to carry the principles and messages throughout the year and to distance themselves from the associated Pagan elements. For the same reasons their dating system is a little different too. Days of the week are number 1-7, with Sunday being the first day of the week. The months follow similar suit being numbered rather than named. This is all pretty straight forward, but extra care should be taken in years before 1752. In 1752, Britain formally adopted the use of the ‘Gregorian’ calendar, and the New Year now started on January 1st, with January becoming the first month. Prior to this according to the Julian calendar the New Year fell on 25th March or Lady Day. Thus a birth, marriage or death recorded in Januar,y entered Quaker records prior to this date may well appear as month no 11, with what we would now recognise as the previous years date. For example 1.11.1720, may actually be 1.1.1721. Of course the calendar change affected all, not just Quakers! Errors in current family history projects including events that took place prior to the calendar change are a common occurrence, often resulting in fruitless searching for a child that died in infancy. As the death 'appears' to have occurred before the birth or baptism, it is often presumed to be a different child entirely, the second of the same name. For example: John Smith, born 1st December 1740 and died 1st February 1740 may well be the same child who passed away at 2 months of age. Please take extra care, especially between the dates 1st January and 25th March in any year before 1752. Returning to the theme of chocolate, Fry’s were the first company to produce and market the chocolate bar in 1837. The non-perishability of chocolate made it popular with seamen, and in 1824 the ‘Cocoa Issue’ became a standard part of Navy rations, paving the way for other services to follow suit. During WW1 food parcels were sent from home, and often contained chocolate - a great morale boost for the troops. In 1914 the Mayor and Sheriff of York (Oscar F Rowntree) sent a tin of chocolates to every citizen of York serving on the front line. Elsewhere, others did their bit too, as reported in the Berwick Advertiser on 25th December 1914: “Chocolate Service – On Sunday afternoon the children’s service at the Parish Church took the nature of a chocolate service. The children were invited to bring packets of chocolate, which would be sent to the soldiers who had left the parish [Glendale]. As a result, over £3 worth of chocolate was received, which will allow of a parcel being sent as a Christmas gift to each soldier.” A timely reminder of the beneficial attributes of chocolate, which is still regarded as an indulgence and luxury today. Questionable practice surrounding methods of production also remains an issue, with fluctuating prices of cocoa forcing some once again towards slave labour. In some cases it has been estimated that only 70% of cocoa futures traded is actually grown. The ‘Fairtrade Foundation’ ensures against human exploitation in all products sold by partners companies. Cadbury, and their Dairy Milk products have been Fairtrade partners since 2009, although no longer a Quaker run organisation, the ethos of human rights remains. Who would have thought that such simple thing as chocolate could be at the centre of so much social history! LinksQuakerinfo.com

http://www.quakerinfo.com/quak_cad.shtml University of Leeds, Special Collections recomeded by 'Family Tree' Magasine https://library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections/collection/718 BBC Magazine http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/8467833.stm

1 Comment

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy