|

Throughout history different tiers of administrative bodies have evolved into the present administrative system – right from our local parish councils to central government. As these systems evolved, the powers they held changed too, some were lost, some were gained, and many became merged with others. At various points through history these administrative systems even governed our ancestors’ ability and freedom to move from one place to another. Where they have survived, the records created surrounding the movement of ‘people’ not only tell a fascinating story but can help us track the physical journeys made by our own ancestors in order to live and work.

How often do I hear the phrase ‘they came from’ only to find with a bit of digging ‘they come from’ somewhere else beforehand! In truth the phrase is most usually associated with the furthest point in history reached by a specific line in a family tree, but how accurate actually is it? As with so many other things in life, the ability to move ‘freely’ and at will was the reserve of the wealthier in society. It is the poorer sections of the populace, however, whose stories are often the most interesting and plentiful amongst the records found in public archives. Movement as a Manorial Tenant - SerfdomOne of the earliest administrative units for which written records survive was the Manor. Back in March I looked at Manorial Records, what they are, and how they can help with local and ancestral research. There was, however, another aspect to the structure and customs of the Medieval Manor that was not discussed and which affected the freedom of movement for some sections of Manorial society. Within the Medieval Manorial system there existed a social hierarchy of Free and Unfree Tenants. In return for his protection, the Manor Lord would expect payment, either in cash or in kind in the form of service. For some Unfree tenants this service saw them tied to the land as Serfs. Free tenants held their lands in exchange for a monetary payment with an obligation to attend the Manor Court. Other obligations were also sometimes attached, but these were dropped and phased out over time. Essentially, although their holdings were held in perpetuity, they enjoyed a large degree of independence and were free to sell and move elsewhere if they chose to do so. Unfree tenants on the other hand, also known as villeins, bondsmen or by other local names, were subject to much more stringent conditions. They too paid a monetary rent, but in addition provided labour to cultivate the Lord’s own land known as the Demesne, carry out repairs, or perform other services necessary to the running of the Manor on which they lived. Crucially, in order to move or live away from the Manor, unfree tenants required their Manor Lord’s permission. Within this band of unfree tenants also existed the ‘Serf’ who enjoyed even less rights over their land, were essentially ‘owned’ by the Manor and were personally ‘unfree’. Whilst this might sound like a form of slavery, serfs could not be bought and sold as chattels but rather were attached to the land and Manor on which they lived. If the land was sold the serfs remained in situ and appear to have been included in the sale. Northumberland Archives features a fascinating article on its website relating to Serfdom based records relating to local Northumbrian Manors. The records contain evidence of individuals required to prove their status as ‘free men’, men earning their ‘freedom’ and of a serf’s possessions passing to the Lord of the Manor at their death. Serfdom was not purely about the work that was done, and different levies and requirements the serfs paid can be found in different manors. In many cases the lord of the manor held the right to receive a serf’s possessions after their death. This could be waived in some cases, as Theobald allowed Adam Donnesheued’s widow and daughter to remove his goods and chattels out of the manor, to his loss of 68 shillings. Some serfs tried to escape. In 1445-6 The prior of Lindisfarne received the goods of Robert Atkynson of Fenham manor after his death, but their accounts also refer to expenses in arresting bringing back John Atkynson of Fenham, Robert’s son, a native ‘meditating flight’. He didn’t run away after this, as in 1453-4 John Atkynson of Fenham, a native of the prior of Lindisfarne paid five shillings in for the merchet of his daughter Mariot.[2] As time passed Unfree tenants became known by the ‘Customary Tenants’ as lands were held according to the Customs of the Manor. The leases known as ‘Copyholds’ were more flexible in terms of conditions as to inheritance and did not attract the former levels of feudal servitude and terms of residency. (The Law of Property Act 1925, extinguished the last of the Manorial Copyhold tenancies which had not already been converted to Freeholds during the 19th century.) Whilst many of us will find evidence of our ancestors within Manorial records, in reality, it is unlikely they will fall within a timeframe to include serfs and serfdom. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating glimpse at how basic rights to move from one place to another was determined and curtailed by a social hierarchy within an ancient administrative system. Settlement & Removal Another form of local governance, which oversaw the free movement of people was the ‘Poor Law’. During certain periods, movement to other areas was necessary for obtaining work etc. Acts of Parliament introduced legislation which defined an individual’s ‘place of settlement’ or where someone belonged and the ability to be ‘removed’ back there should unemployment or destitution strike. Although containing notable differences, the basic principles of ‘Settlement and Removal’ was similar in both England and Scotland. For the purposes of this blog, the legislation and policies referred to, have been drawn from the English system. The intention being to discuss the implications of movement restrictions and the records it generated rather than the finer points of the Poor Law in either Country. Prior to the Reform Act of 1834 the administration of ‘Poor Relief’ was overseen by the Parish. (In Scotland, the Poor Law was reformed in 1845). In England, the first Act governing the relief of the poor was passed in 1552. In Scotland it was 1572 and entitled “For punishment of strang and idle beggars, and reliefe of the pure and impotent". In England several amendments swiftly followed to include a classification of the different kinds of ‘poor’ (deserving and undeserving) (1563), compulsory collection of tax to pay for poor relief (1572) more powers to raise tax for poor relief and overseers appointed to collect it (1597) a national standard and compulsory poor rate set (1601) and finally in 1662 the first ‘Act of Settlement’ was introduced. The ‘Act of Settlement’ determined which parish would be liable to pay poor relief to an individual should they find themselves in need, based on a set of residency criteria. The Place of Settlement, or where someone ‘belonged’ was determined as a place someone had been born or had worked for a certain period of time. Crucially, the Act allowed for the removal of people back to their place of settlement should they become unemployed, failed to find work within 40 days, or, were unable to pay a rent on a property worth £10 per annum. A revised Act of Settlement passed in 1697 set out more precisely defined rules for settlement qualification:

The new Act allowed strangers to settle in a parish, so long as they could support themselves and brought a certificate proving their place of original settlement with them. These ‘Settlement Certificates’ were extremely important documents as they proved entitlement to poor relief by guaranteeing folks could return to their parish of settlement should they become destitute. Certificates were issued by a church official in the original Parish and were to be passed to the corresponding church official in the destination Parish. The officials being Church Wardens or Overseers of the Poor depending on the date of issue. Certificates that have survived, usually date from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and contain the following information:

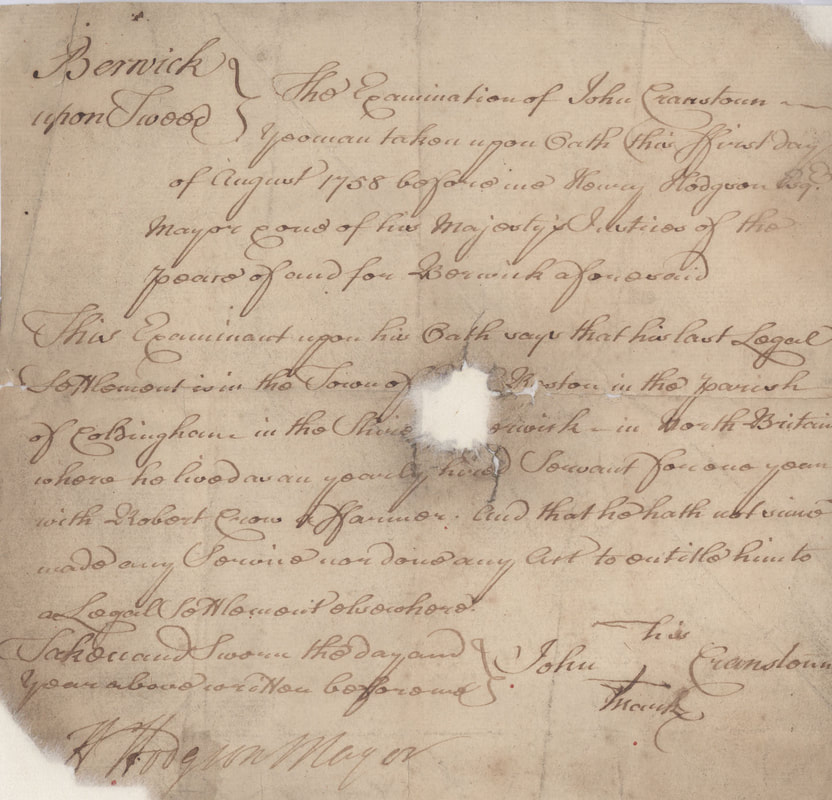

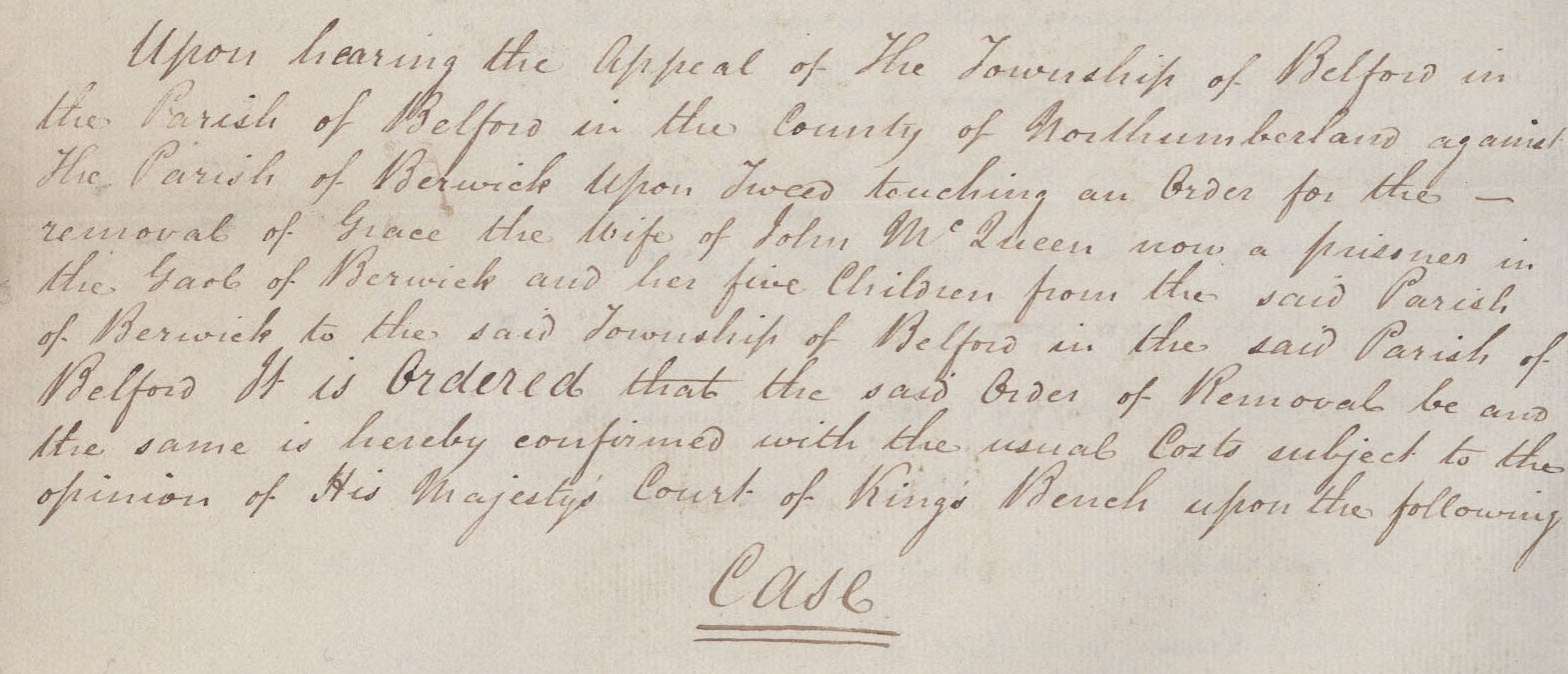

If no certificate existed and the individual became chargeable to the parish, they would be examined by the local Justice of the Peace. They would be questioned as to where they had been born, how long they had lived and worked in the parish, marital state, number of children etc. Once the place of settlement had been established a ‘Removal Order’ to the chargeable parish could be issued, along with a bill for expenses incurred by the parish where the individual or family did not ‘belong’. Removal orders would include:

It was quite common for the original parish of settlement to exercise their right to dispute a removal order. When this happened the case would go to the Quarter Sessions Court. Where they have survived amongst the court records these early examinations and removal orders can be goldmines of information. The above illustrates how the place someone belonged and their ability to move freely to live and work was historically defined by a tier of legislative administration designed to encompass the ‘care’ and governance of ‘the poor’. The freedom and ability to move was not a totally straightforward process, but did come with a theoretical safety net. Ironically it is those ancestors who required this intervention that have potentially left more evidence of their passage. The Poor Law is an extensive subject and decidedly more far reaching than the snippets concerning ‘Settlement & Removal’ briefly covered here. There are many other aspects to its administrative which can provide further rich pickings for both the family and local historian and are well worth exploring. [1] ‘Reminiscences of Thomas Marshall of Berwick by Himself’ Berwick, 1835, is available through the National Library of Scotland

https://search.nls.uk/permalink/f/sbbkgr/44NLS_ALMA21536844970004341 [2] Northumberland Archives, ‘Tied to the land – serfs from manorial history’. https://www.northumberlandarchives.com/2017/04/07/tied-to-the-land-serfs-from-manorial-history/#more-3402

2 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy