|

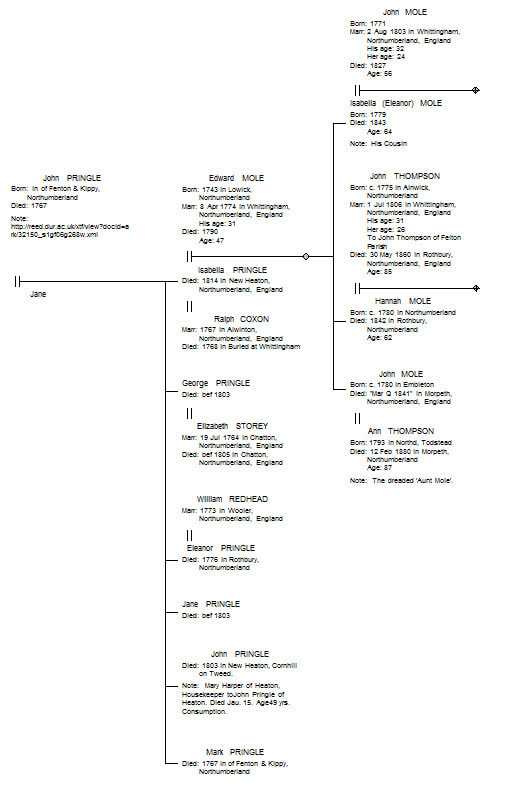

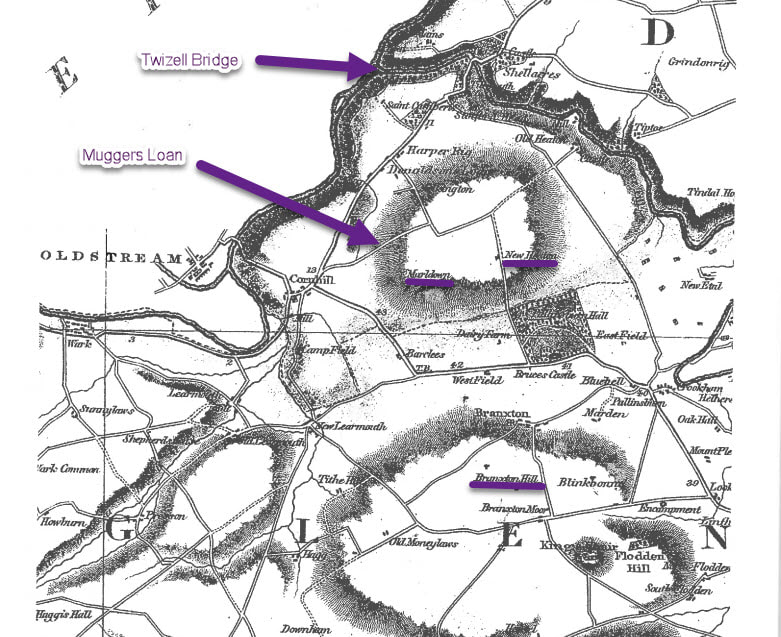

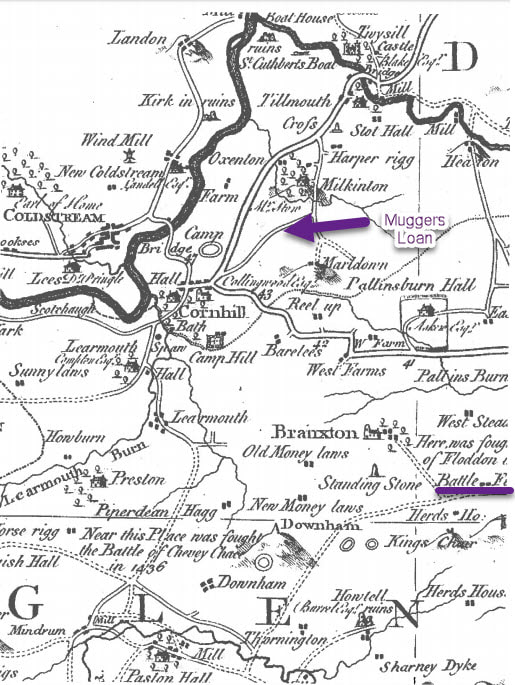

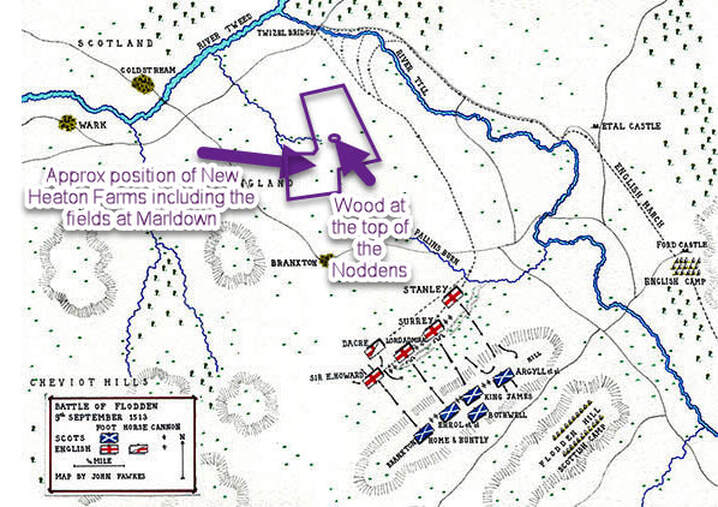

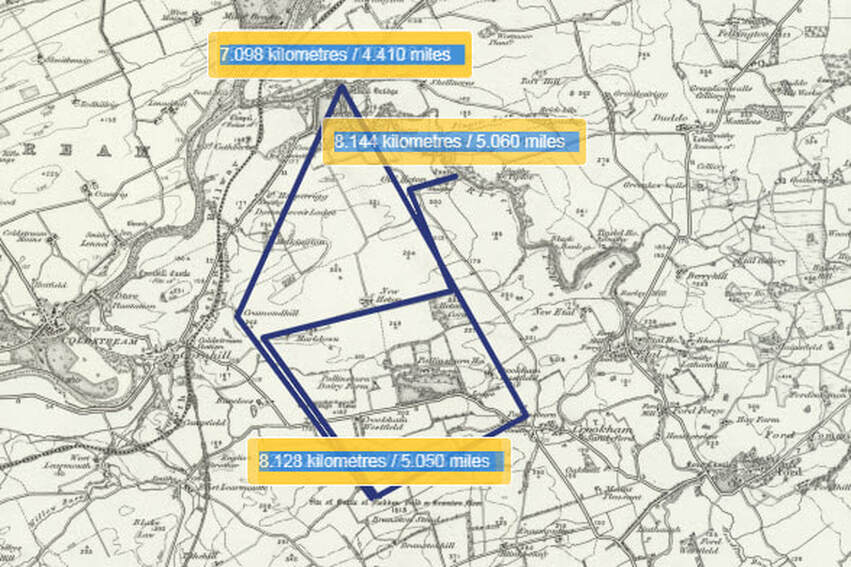

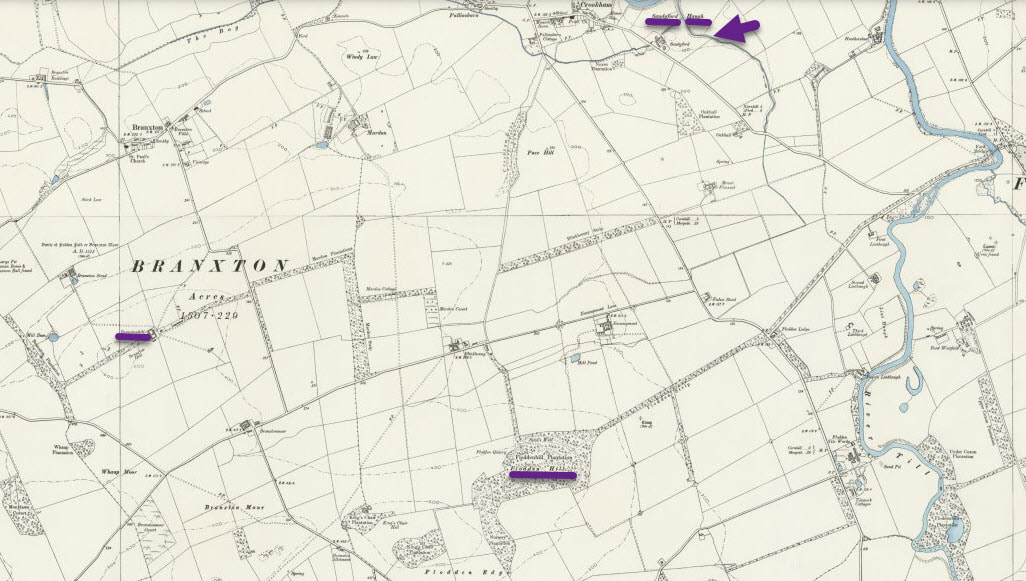

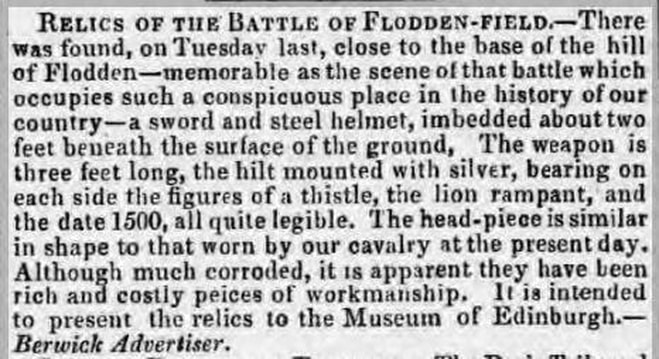

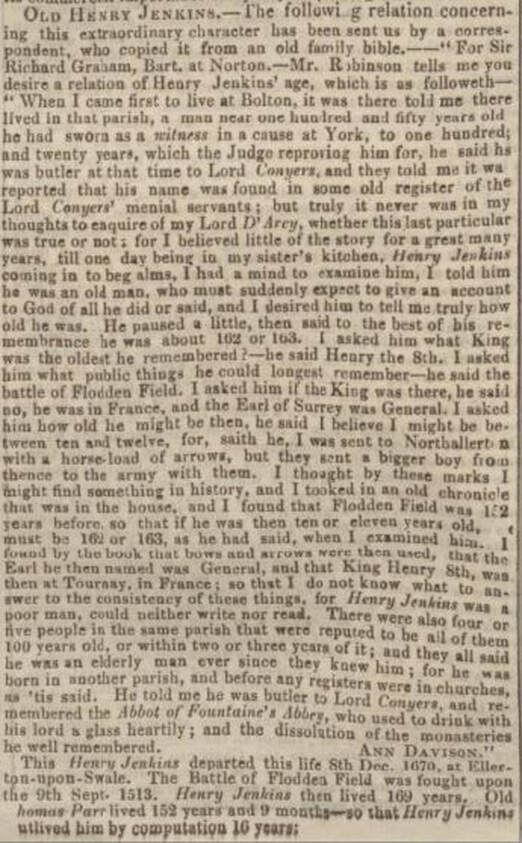

Last month Rosemary Dixon-Smith looked at the story of the ‘Redeswire Affray’ and how stories recounting this Border skirmish may have circulated amongst her ancestors in 19th century Northumberland. Here she was alluding to the ‘oral tradition’ which is the means by which events of the past have been verbally perpetuated into the present, particularly amongst local communities. Many of us will have encountered it in our family history too! However, over time embellishments and omissions often mean that the truth, although still there, has become distorted and is somewhat harder to piece together. So what IS history? Simply put it is the study of past events, particularly in human affairs or a series of past events connected to a person or thing. It is perhaps the origin of the word that provides a more practical definition. ‘History’ as derived from the Greek ‘Historia’ – meaning 'inquiry; knowledge acquired by investigation' – is the past, as it is described in written documents. The period before the existence of written accounts is therefore called ‘pre-history’. Rosemary’s blog coincided with the annual Jedburgh’s Callants Festival and the Redeswire Rideout in early July. These Festivals and Civic Weeks hosted by many Scottish Border towns run throughout the summer and celebrate their unique identities, individuality and the roles their town played in the history of the Border. They culminate in Coldstream with the Flodden Rideout to Branxton Hill and the service of remembrance for the men of both nations that fell at the Battle of Flodden which took place in 1513. For those who have not heard of the Battle, it was a crushing defeat for the Scots, whose King, James IV was slain along with many of the Scottish nobility at the hands of the English. It might seem strange then that such an event should be remembered with such passion 5 centuries on, particularly by the side that essentially lost. But then the Borders and indeed the Battle itself remain a bit of an enigma! I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t aware of Flodden. As a youngster the annual pilgrimage made around Christmas time to Tithe Hill, the then home of my grandfather’s sister Mary and her husband Willie Davidson, which lies almost adjacent to Branxton Hill. As my interest in family history grew I became aware of historic farming connections in land to the east that faced the battle site and over which the English army undoubtedly trod as it marched to meet the Scots on that fateful day. Aside from the connection to the Greys of He[a]ton who held the estate from circa the 13th century, a paternal 5th great grandmother penned her last will and Testament at the farm of New Heaton on 5th May 1814.[1] She was Isabella Pringle, twice widowed and the last surviving child of John Pringle of Fenton & Kippy. Isabella had married Ralph Coxon in 1767 and following his death in 1768, married secondly, Edward Mole, with whom she had 4 known children. Edward Mole died in 1790 and Isabella was appointed administratrix of his estate with Edward Anderson of Glanton and Thomas Vardy of Rothill standing surety for the penal bond of £560. In 1804 Isabella’s last remaining brother John Pringle died intestate at New Heaton on 10th January 1802. Isabella was again appointed administratrix by the court, but on this occasion in addition to Edward Anderson (junior) of Glanton, (Senior had died in 1799), Edward Pringle of Snitter stood surety to the rather heftier penal sum of £18,000, or some £1.2 million in today’s terms. Undoubtedly there was a familial connection between the various parties, some of which are known and for others the exact details still need to be conclusively established and are therefore, the subject of ongoing investigations.[2] As chance would have it, I myself came to farm at New Heaton through marriage, at which point elements of my past and present collided. It was then with my feet firmly planted on the ground that the English army may well have passed, and with the battlefield in places in full view, that my interest in Flodden was reignited. This interest was then cemented through a project of voluntary re-examination of some of the original documents pertaining to the Battle preceding the quincentennary commemorations in 2013. However, the project was naturally limited as to the number of documents it could cover, and therefore in many ways left more questions unanswered than it solved. When combined with the history of area of the region in the early 16th century it was only natural that other aspects of the Flodden campaign should form the topic of my prize winning MLitt dissertation ‘Food for Thought’. A 24 page document containing quantities of corn purchased and shipped from Hull to Newcastle for the English army formed part of the primary evidence in support of that specific ‘argument’.[3] However, the document alone was insufficient to test the theory and required evidence drawn from other sources, such as corn imports, rent rolls and archaeological findings. Now that the dissertation is behind me, my interest in the history of the area and events surrounding the campaign has not diminished but rather, the evidence uncovered through the research has prompted me to challenge long established theories still further. Mainstream accounts of the English army’s route of approach skirting around New Heaton to the east rather than either passing through it, or skirting it to the west, makes very little sense at all, armed as I am with a first hand working knowledge of the terrain. Most accounts state that Surrey outflanked the Scottish army, and suggest his intention was to take Branxton Hill himself, and from there to engage on more equal terms with the Scots who had been dug in on the facing Flodden Hill. Yet the approach route that is shown, which roughly follows the line of the road from Tillmouth to the A697 today, crosses land that would have a) been in view b) crosses other areas of potential bog and c) necessitates the English army navigating a second area of bog below Pallinsburn and then marching directly in front of the entire Scottish army to take its position. There are many books on the market that look at the campaign from different angles. However, a glance at the footnotes, endnotes or bibliography clearly show that the same old sources are rolled out time and time again. More annoying still is that the majority of the sources cited refer to the ‘Calendars of State Papers’ rather than the original documents themselves. The ‘Calendars’ are summarised extracts of document contents. In some cases they are extensively condensed and barring a couple of salient points bear little resemblance to the full contents of the original. Whilst useful for pinpointing primary documentary sources that may contain information of interest, they cannot be considered primary sources in their own right. Yet, time and time again the same condensed extracts are interpreted, quoted and cited – of course it is far quicker and easier than ploughing through pages and pages of 16th century script – but by doing so, they are at the mercy of the compiler of Calendar’s own opinion as to what is important and what is not. Furthermore, not all documents have even been ‘calendared’. There will doubtless be more clues and evidence as yet lying undiscovered in the collections held by The National Archives.  View of supposed English approach from Pallinsburn. Etal Castle is clearly visible. From this angle and position which is also taken from the mid-Scottish Line, it is clear to see that the land falls away and without the trees a body of men would have been in clear sight. The ridge of hills in the background have Berwick at their eastern foot. Clearly some authors have actually visited the battle site (which is a bonus) and chapters of their books are adorned with bonny photographic plates. However, I have yet to see one that has looked at the Battlefield from the English perspective much beyond the view from Pipers Hill. There are few with pictures taken from the hill itself looking towards the terrain of the English approach, but alternative approach routes themselves have not been considered. The only account I have read to date to challenge this established route is ‘The Battle of Flodden and the Raids of 1513’ written by a Col. Fitzwilliam Elliott in 1911.[4] Had the authors done so, one landmark in particular would have stood above all others and possibly prompted further investigation. It is the hill that stands roughly in the centre of New Heaton, at the top of the ‘Noddens’ – standing at some 306 meters. Today it is a Trig Point and more obvious because of the wood that stand on its summit. To either side the land drops away; to the south the steading of New Heaton sits in a dip before rising up again to a ridge of 260 meters in height which runs in a similar trajectory to the hills above Branxton before sloping away just beyond Marldown and Cramond Hill. This ridge forms a false skyline when viewed from the approximated lines of the Scottish troops; to the north of the Noddens, the land again dips away into a valley at the bottom of which runs an old By-way known as Muggers Loan, which runs along the course of the Oxendean Burn.[5] To my mind for the outflanking manoeuvre, as it so often described, to have been successfully achieved, the route of at least a substantial body of the army, would more likely have passed through either Donaldson’s Lodge or New Heaton. Two possible routes through New Heaton are the line of Muggers Loan where the army could have passed unseen until it emerged around the bottom of Cramond Hill or Marldown, or, along what is now known as the ‘Thrieprig’ track, where again a body of men would have been hidden behind the false skyline, only emerging on the top of the ridge near Marldown. A view that was clearly shared in part by Col. Elliott in 1911. By approaching the field from this direction would also have eliminated the necessity to negotiate the boggy ground below Pallinsburn. An approach taking any other route from the crossing point of the River Till would have been, at least in part, clearly visible to the Scots. If Branxton Hill was indeed the objective then the alternative routes are also the shortest. That they travelled unseen is suggested in Hall’s Chronicle by the Lord Admiral sending his ‘Agnus Dei’ to his father alerting him to the fact the Scots had changed position.[6] This would certainly infer that both the Admiral and his father travelled with the Scottish army out of their field of vision, as it moved from its encampment on Flodden Hill to that of Branxton. However, the same paragraph mentions the Admiral first had sight of the Scots army after crossing the burn at ‘Sandyfford’. The only Sandyford to my knowledge lies to the east of Crookham, and if Hall is to be believed, this would contradict my earlier the theory in every way. The Admiral’s father the Earl was reported to have been at his east again, which makes even less sense if the objective was Branxton Hill and the battle was fought on the site alleged. The Sandyford burn runs north into the Till, to cross it from the east heading west the Admiral is most unlikely to have crossed the Till at Twizell Bridge. Furthermore why would he? Travelling via Sandyford would also have added approximately another mile to the Pallinsburn route. It would however, have made (a little) more sense if Surrey’s objective was not Branxton Hill at all, but to have engaged with the Scots in their original position.[7] The inability of the English to see the Scottish position is attributed by Hall to a veil of smoke from fires deliberately lit in the Scot’s camp. With a prevailing westerly the smoke could not have covered the Scots as they moved position. If not, the the veil of smoke would surely have been between the English at Sandyford and Branxton and thus obliterated the view? There are three main contemporary accounts which are referred to time and again; the ‘Articles of Battle’ although unsigned, looks to have been written by the Admiral himself, The Trewe Encounter and Hall’s Chronicle. The battle is also mentioned in various pieces of correspondence including a letter written from Bishop Ruthal to Wolsey on 20th September 1513. Herein lies a problem in itself as all of the accounts (with the exception of Ruthal) are attributed to the Howards, their followers, or on behalf of the King and none agree in the detail. They were mounted (Hall), they were on foot (Ruthal), they travelled from 5am to 4pm (Hall) and 8 miles to the Battle (Ruthal) etc. The latter is an impossibility if they travelled via Twizell as it is 7.4 miles in a straight line from Barmoor to Twizell alone, with approximately another 5 miles to the Field had they travelled via Pallinsburn as suggested. However as the crow flies, and had the army (or part of it) crossed the Till around Etal the distance from Barmoor to Branxton is approximately 7 miles. Regardless of the historical project, the ability to transcribe, read and understand historic manuscripts is only half of the challenge, the remainder being the ability to interpret and contextualise their contents. It is necessary to raise the further questions of; by whom, why, where, when and for whom each ‘document’ was written. The ‘by whom’ and ‘for whom’ are clearly important factors when considering the various accounts of the battle. When referring to any primary written source, an assessment of the reliability and motives of the author are of paramount importance. In the case of Flodden what has been left unsaid is as important as what has been ‘documented’. There is no record of Surrey’s original intent, whether that be to station his army on Branxton Hill, or to engage with the Scots in their original position. Then again, by not recording the aims of the manoeuvre, the leaders of the English army could not be admonished had those aims not been achieved. A great many of the details of the final day remain unknown, open to interpretation and opinion, which is not helped by the lack of archaeological evidence. With the exception of reports of a couple of cannon balls, one of which was allegedly found on the slopes of Marldown (what could it have been doing there?) and other unsubstantiated finds, no archaeological evidence has been found to date that places the battle in its current location. Of course there are many reasons why this could be the case – one being the documentary evidence in the form of accounts of armour being stripped from the bodies of the fallen and sold from the field – where money is concerned there is usually more than an element of truth – the other is that prolonged agricultural activity and quarrying in the immediate area have obliterated what few artefacts that may have remained. I am not suggesting that my own theories are necessarily correct, but knowing the terrain first hand as I do, they must at least proffer a viable alternative. As it stands it would appear the English Army of circa 20,000 fighting men, with their ordnance in tow, marched upwards of 14 miles, navigated difficult terrain en route, in the form of a gorge at Heaton Mill and a bog at Pallinsburn, and then began a battle at 4 o’clock in the afternoon from which, although significantly outnumbered and having had nothing to eat for a couple of days, they emerged victorious. History is in the main just that – ‘his story’, after all what could a mere woman possibly know of tactics, terrain and common sense. The history of war-fare still remains a male preserve. However, there is a reason the saying tells us to go to the horse’s mouth and not its backend! Speaking of which, a trick was clearing missed in failing to interview the last known survivor of the Battle – one Henry Jenkins, who died in 1670 aged 169 years! Now that really IS a canny story! (Postscript - we sold New Heaton in 2011, nonetheless I still look directly onto Branxton Hill today. Ironically, today it is from where I receive my internet signal!) [1] Sir Thomas Grey of Heaton wrote the medieval history ‘Scalachronica’ whilst a prisoner of War in Scotland. Andy King examines the work in some depth in his MA Thesis of 1998. King, Andy (1998) Sir Thomas Gray's Scalacronica: a medieval chronicle and its historical and literary context, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4842/

[2] Patience Anderson sister of Edward Anderson senior married John Grey in 1767, before purchasing Middle Ord they lived at Old Heaton. Edward Pringle of Snitter’s wife was Margaret Vardy. Two of Edward Pringles children married Re[a]dhead siblings. Numerous connections between Pringle, Thompson, Hogg , Coxon and Readhead. Only familial connection not proven Isabella Pringle to Edward of Snitter. [3] Accounts of Richard Gough E101 56 28. [4] Col. Fitzwilliam Elliott, 'The Battle of Flodden and the Raids of 1513' archive.org/details/battleoffloddenr00elliuoft/page/n135 [5] ‘Mugger’ is the old word for Gypsy or Tinker. [6] Hall Chronicle https://archive.org/details/hallschronicleco00halluoft/page/560 [7] This same reference seems to have caused some confusion for the Battlefield Trust too. See page 8. https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/listing/battlefields/flodden/ If, like me you are trying to track down your Pringle Forebears, a first step may be to contact the Clan Pringle Association where you will find more details on how to join both the Association and also the Pringle DNA project.

2 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy