|

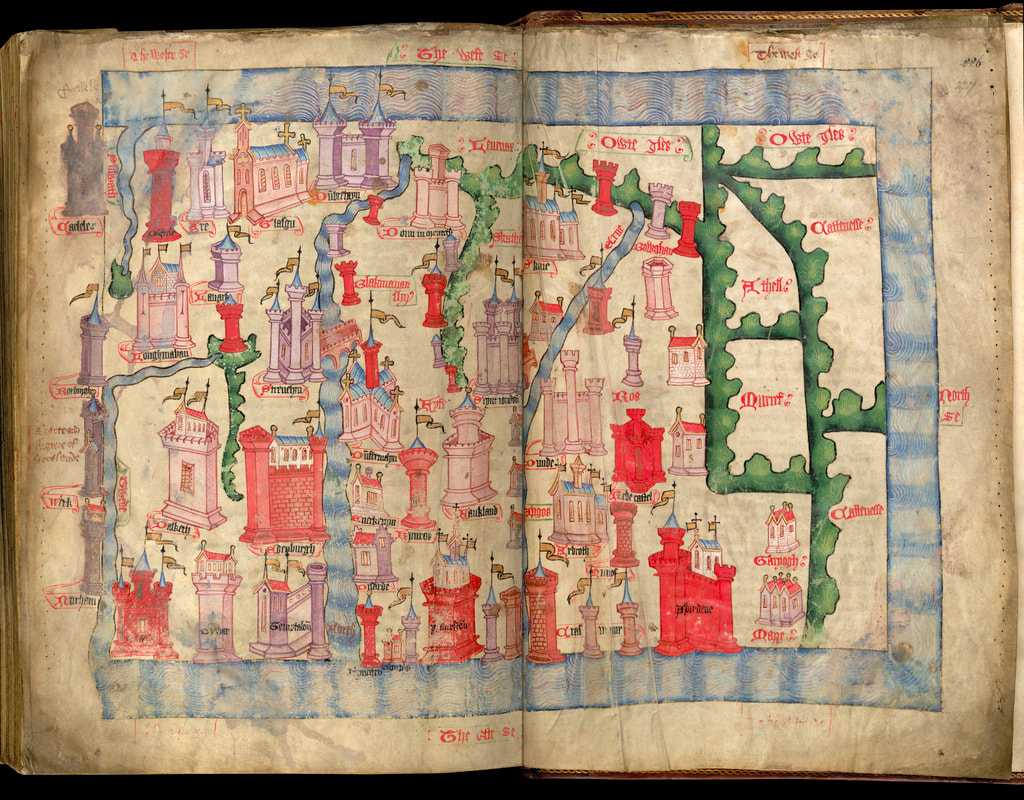

Having acquired the basic skills required to decipher the handwriting in old documents from last month’s post, now is perhaps an opportune moment to introduce the subject of Diplomatics. After all there is an awful lot more to a document than just its contents! To be deemed trustworthy an historic document must be deemed both authentic and reliable. ‘Reliability means that the record is capable of standing for the facts to which it Diplomatics is defined by the OED as: The science of diplomas, or of ancient writings, literary and public documents, letters, decrees, charters, codicils, etc., which has for its object to decipher old writings, to ascertain their authenticity, their date, signatures, etc. As such, it sits side by side with palaeography, a sister science so to speak. How authentic is your document?Documents have been forged since history began and is by no means a recent phenomenon. One of most famous forgeries of the 20th century were the Hitler Diaries; On May 6, 1983, West Germany’s Federal Archives released the results of a forensic investigation into what turned out to be one of the greatest hoaxes of the 20th century–the Hitler diaries. Just weeks earlier, the newspaper Stern had announced the discovery of 60 small notebooks, purported to be the personal diary of Adolf Hitler, covering his rise to power in the 1930s and later years as Nazi leader and architect of the Holocaust. The newspaper and its parent company paid journalist Gerd Heidemann a small fortune for the items, which Heidemann said had been recovered from an airplane crash shortly after the end of World War II and then smuggled to the west from Communist East Germany. The announcement made headlines around the world—and unleashed a firestorm of criticism. The newspaper restricted access to the diaries, allowing several World War II experts only a quick look at the documents. Once excerpts from the diaries were released, however, the story began to fall apart. In early May, the Archives, who looked into the matter at the request of the West German government, announced its findings: The Hitler “Diaries” were fakes, and bad fakes at that—the handwriting didn’t match, they had been created using modern materials and much of the content had been plagiarized. Nobody knows what happened to the millions of Deutsche Marks paid for the documents, but both Heidemann and his accomplice, forger Konrad Kujau went to jail.[2] Of course, most of us are not concerned with the intricacies of such ancient documents and are unlikely to conducting forensic experiments into the contents of ink and glue to prove a documents authenticity. I think whilst we all have the basic common sense to realise that a Last Will and Testament written in biro on ‘Basildon Bond’ paper purporting to date from the 1750s is a fake, the history of paper is, nonetheless, a fascinating subject. When the Accounts of the Newcastle Chamberlains 1508-1511 came to light in 1978, it was the composition of the paper and indeed the watermark (which proved to be French) that provided part of the proof of their authenticity.[3] If the history of paper and watermarks is of interest to you, The University of Warwick as some very useful links. It is, however, as well to be aware that forgeries, particularly concerning the ownership of property are far more common than may be imagined. Only this week whilst looking something up in NRS catalogue concerning the family of Borthwick of Borthwick, the catalogue entry contained the stark warning: Section 2 of the catalogue covers peerage case papers. It includes some forged title deeds, while some genuine titles in section 1 are endorsed with forged writings as part of the peerage cases. An introduction to section 2 explains in more detail the reasoning behind the forgeries[4] That is a very brief overview of authenticity, but what about the aspect of reliability? How reliable is your document?Stepping back a few hundred years to John Hardying chronicler to both Henry V and Edward IV in the fifteenth century. Hardying is described by Scottish Historian Dr Alastair Macdonald as ‘… a slippery individual. By his own account he was a spy; he was also a forger; and he appears to have been a thief as well.’ Much of Hardyngs fraudulent activity surrounded the justification for English suzerainty over Scotland and the two versions of his Chronicle ‘offer radically varying accounts of English political history in Hardyings own lifetime’. Each version had been manipulated to reflect the interests of his ‘employer’, the King. In such a way he supported the Lancastrian claim of Henry V in the first version and that of the Yorkist Edward IV in the second. It is therefore easy to see how historical fact can be easily distorted by taking the point of view of an author at face value. (More about John Hardying can be found on the British Library Medieaval Manuscripts Blog https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/09/mapping-medieval-scotland-between-politics-and-imagination.html ) When considering a source, any source, ask yourself how reliable is it likely to be, and just how credible is the author – would they really have been privy to the intimate details of the subject? For example: Is the diary of Mrs Miggens the baker’s wife likely to contain accurate information concerning the family affairs of Mr Johnson, the Landlord of White Horse Inn? If Mrs Miggens turns out to have been Mr Johnson's married sister, then it is far more likely she will be a credible source of information about the Johnson family than if she was merely the town’s gossiping busybody. However, this still requires an element of caution. We saw in an earlier post how Mr William Brewis of Throphill felt most aggrieved at not being a beneficiary of a Will. Perhaps he had either forgotten, or did not know that the deceased had much closer family than himself when he wrote: Died at Whittingham on Wednesday 7th February John Carnaby Esq our cousin …it is said he has left his property which is said 15 or 20,000 to Dr Trotter of Morpeth, should it be so, it is said he was not capable of making his will but the Dr had haunted him to settle his affairs upon the Hargreave family of Shawdon, how that may be time will determine, he has no relative but our family and more strange, never sent word that he was dead, or invited to his funeral!!! For both amateur and professional historians there is a simple methodology which can be applied to research using documentary sources. Its a series of memorable questions to ask ourselves, and these are; Who?, What?, How?, Who else?, Why?, Where? and When?

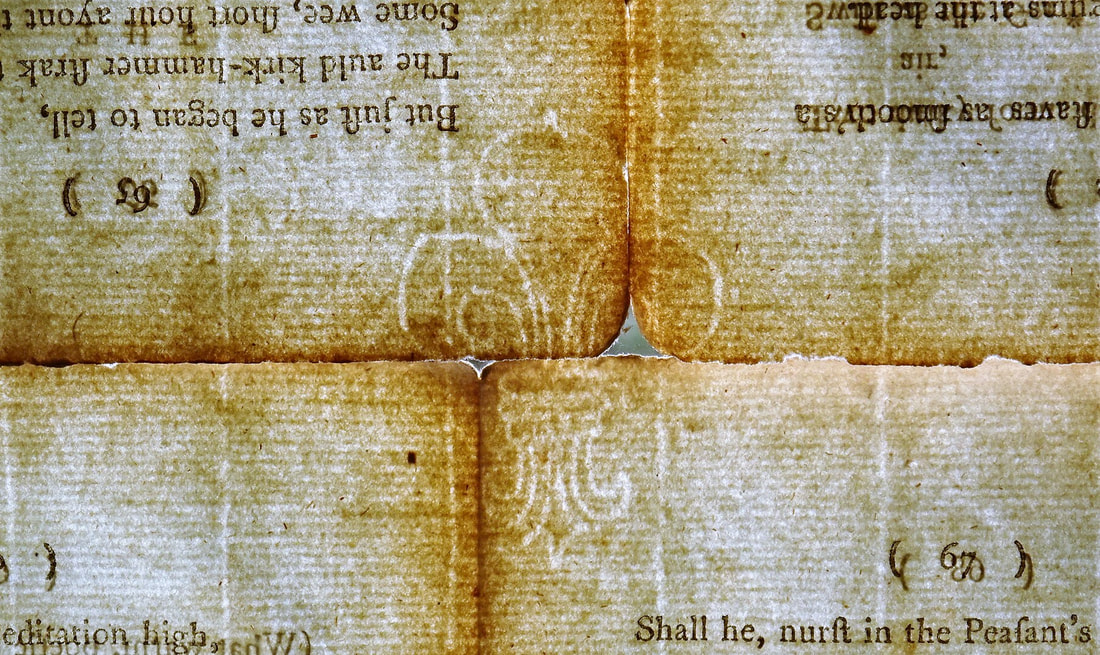

Following these simple steps can also help identify what type of document it is. The language of many official documents is highly formulaic and often specific to a documents purpose. It crops up in more places than you perhaps realise. Although there are many more, here are just a few of the types of documents that follow a set format:

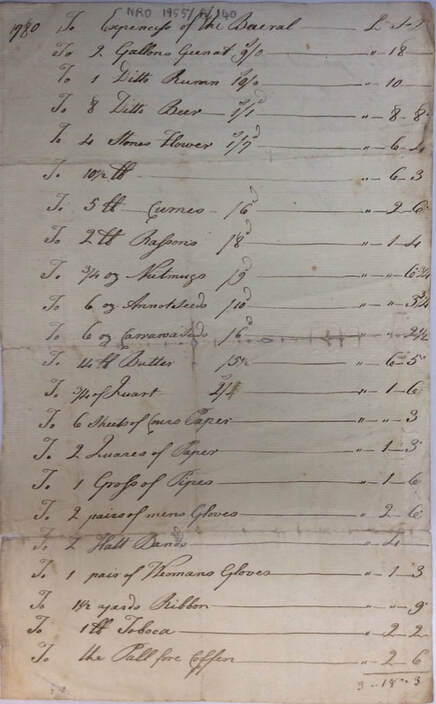

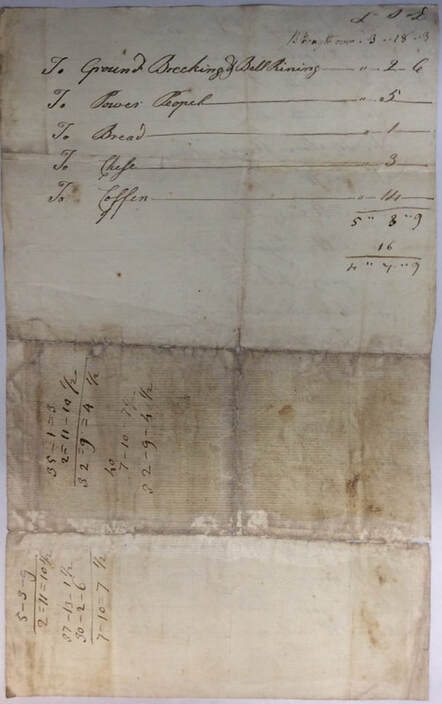

If you are just itching to practice both the skills of palaeography and diplomatic by following the methodology outlined above, below is a document dating from 1780. It is an account for the burial expenses of an unknown individual. At first glance it might appear to be just a list of the costs incurred, but on closer inspection it is packed with historical information and contains subtle clues as to who the ‘writer’ may have been. (If you would like a large image to work with please email me & I shall send you a copy) For those of you of a mind to have a go and would like some feedback on the conclusions you have drawn you can post them in the comment sections below. Alternatively, if you would rather do this privately you can email them to me by following this link. If you are at all interested in how to go about describing the hand and other features of an old document, I am happy to supply a copy of my analysis of Jane Austen’s Will as an example. Please just ask. It scored reasonably highly in my university studies at A3, the main criticism being I hadn’t compared to other documents written in her hand at earlier dates. The original will (along with a transcription) is available online at The National Archives. Although it is only 12 lines long, it contains a mixture of formulaic and personal language and some interesting points worthy of note to any family history researcher. [1] Heather MacNeil, ‘Trusting Records: Legal, Historical and Diplomatic Perspectives’, London: Kluwer, Academic, 2000. [2] Inside History, https://www.history.com/news/historys-most-famous-literary-hoaxes [3] Joan Philipson, ‘A Note on the Paper’, C M Fraser ‘The Accounts of the Chamberlains of Newcastle upon Tyne Chamberlains 1508 -1511’ Newcastle, 1987. [4] National Records of Scotland, GD350, Borthwick of Borthwick. Further Reading and Useful Links The Will of Jane Austen, 27 April 1817.

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/museum/item.asp?item_id=33 Caroline Williams, ‘Diplomatic Attitudes, From Mabon to Metadata’ Journal of the Society of Archivists, Vol 26, 2005, Issue 1. Available through Taylor & Francis Online. ££ Society of American Archivists https://www2.archivists.org/glossary/terms/d/diplomatics Heather MacNeil ‘Trusting Records in a Post Modern World’. Association of Canadian Archivists https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12793/13991 MacNeil, Heather. ‘Trusting Records: Legal, Historical and Diplomatic Perspectives’, London: KluwerAcademic, 2000. The University of Warwick, Paper and Watermarks, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/ren/archive-research-old/lima/paper/ Peter Goldsborough, Gordon Donaldson ‘Formulary of old Scots Legal Documents’, Edinburgh, 1985 published by The Stair Society. Its like ‘hens teeth’ to find a copy to purchase but ‘WorldCat’ lists the libraries where it as available to view.

2 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy