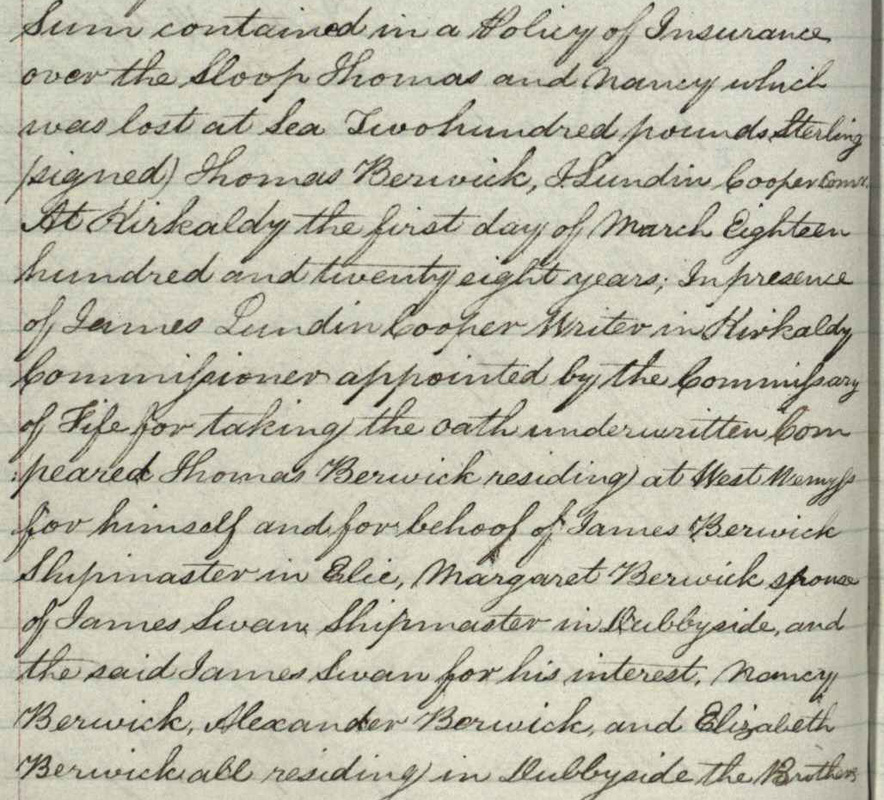

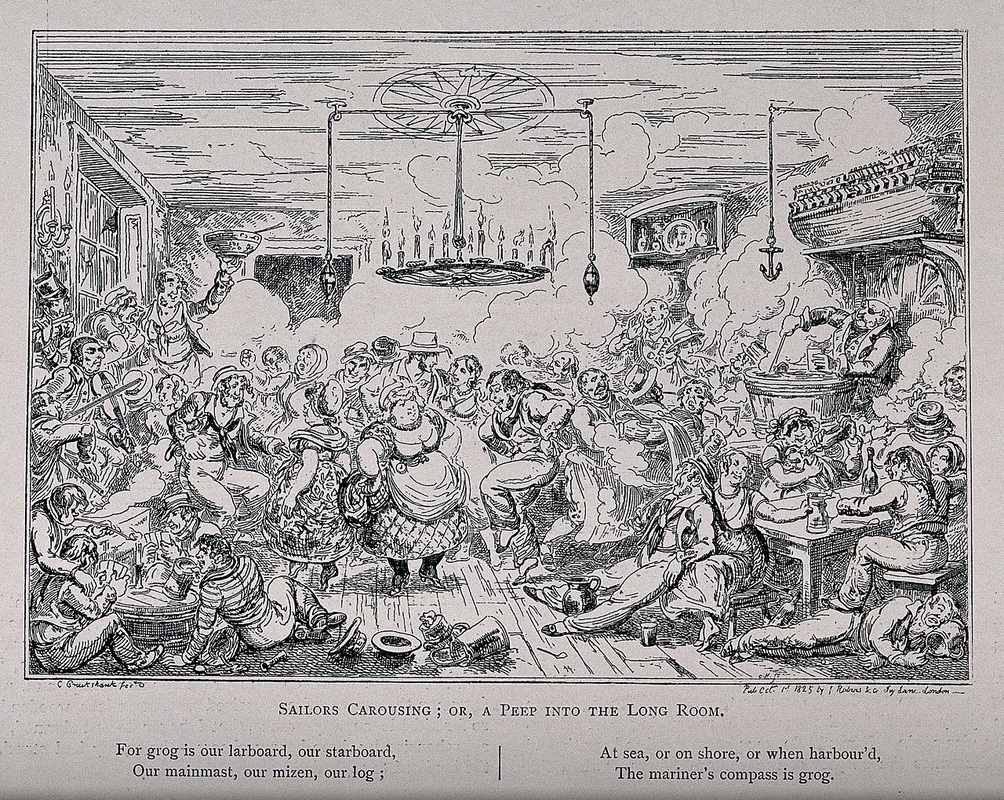

IntroductionShould you be familiar with my monthly blogs you will remember ‘A Certain Class of Vermin’ back in January 2015 which amongst other matters, touched on the nefarious activities of a certain Thomas Berwick, a native of Kirkcaldy in Scotland. To recap: Thomas, was convicted of defrauding insurance companies by deliberately scuttling his own ship ‘The Severn’ and was sentenced to 20 years transportation in 1867. He arrived in Albany on 10th January aboard ‘The Hougoumont’, the last convict ship to leave British shores for Australia. He earned his freedom and respectability teaching in a government school in Jarrahdale before his death in October 1891. During his trial it became apparent that this was no ‘one off’ opportunistic crime, and that he had not acted alone. Indeed, several other incidents were brought before the judge that involved ships jointly owned by Thomas, his father (Thomas snr) and his mother Joan McDonald. Well I couldn’t leave it there now could I? Further motivation to dig deeper came from Philip Barnes, a descendent of the aforementioned Thomas Berwick, who contacted me concerning research for a book on his family’s history. Together, we are discovering a seafaring family of some longevity that operated out of the ‘Lang Toun’ of Kirkcaldy. Indeed one of the earliest records to come to light thus far (40 years earlier in fact) is the account of: ‘Two sailing vessels belonging to Messrs. Berwick of Methil [that] were lost on the 8th March 1827. The THOMAS & NANCY was lost with all hands off Kirkcaldy and the EUPHEMIA was wrecked off Buckhaven.’ The probate record for Robert Berwick, an Uncle of convict Thomas, who went down with the ‘Thomas and Nancy’ has provided some interesting information. Not only was the entire value of his estate at the time of his death the £200 ship’s insurance (sound familiar?), it has given us the names of his numerous living siblings on which to base further research. However, our favourite piece of information thus far unearthed has to be this account from circa 1824 which appeared in the New Zealand press some seventy years later. It concerns an even earlier Thomas Berwick, aka ‘Black Tam’, the grandfather of convict Thomas and his final voyage. The article is packed to the ‘gunwales’ with information making it a little gem for historians. It has to be said this particular account is more reminiscent of ‘Captain Pugwash’ than the ‘Onedin Line’, and although undoubtedly embellished, is nonetheless, extremely amusing! The original has been kindly transcribed, annotated and shared by Philip. We both hope you enjoy reading it! Black Tam's Nose(I know this is Irish rather than Scottish, and takes a wee while to load, it's just something to put you in the mood while you read!) National Library of New Zealand, Oamaru Mail, Volume XX. Issue 6140, 4th January 1895 Transcribed and annotated by Philip Barnes. "This is a short sketch of a seafaring incident of 70 years ago. The schooner Jean, commanded by Captain Thomas Berwick, sailed between Kirkcaldy and the Baltic, bring flax, hides, reindeer tongues, wheat, timber, tar, and other such Russian, Prussian, or Scandinavian produce as ready sale was found for among the Lang Toon [a nickname for Kirkcaldy, with its long main street] merchants, or in Leith, whence the schooner took various “notions,” as the Yankees say, saleable at Christiansand, Christiania, Copenhagen, Carlscrona. Dantzic [now called Gdansk], Riga, Helsingfors [now called Helsinki], or even St. Petersburg, where the crew would hobnob with “Jacky Dobra.” [19th century sailor slang for a Russian.] Now and again she would take a trip round North Cape to Archangel, on the White Sea, and would have narrow escapes from being caught and nipped in the ice. But Captain Berwick, better known as Black Tam, was a most capable navigator, when he was not “incapable,” which happened seldom while on duty. When the incident to be related occurred, Black Tam was no longer distinguishable by his soubriquet, nor at the critical juncture was he at all capable. In his earlier manhood he had been a ‘gay black-aviced chield [i.e., a merry, swarthy child],’ and was well-known in his native port, and all others that he frequented, not only for his thorough seamanship, but for his thoroughly vigorous dealings with all on board his tidy craft. A sailor trained by him never need to seek twice for a berth. If there was no real vacancy on the ship he fancied, some lubber had to shift his chest to make way for him. Among the se-faring folk of Fife, the fisher folk especially, a nickname was, and to a great extent is yet, the rule rather than the exception. ‘Black Tam,’ therefore, received the addition to his baptismal name with the same feelings as Highlandmen and Lowlanders accept those which, with their posterity, became the family name, as Roy, Dow (Dhu), Bain, Gorm, Reid, Black, Fair, Blue, etc. At the time of this story Black Tam was rather over sixty: indeed, his ‘three score years and ten’ had nearly run their course. He was rather down in the mouth, because he was taking his last voyage; but he was ‘making the pace’ just to spite the sadness of it. He had resolved to remain on shore after this, and spend the remainder of his life in comforting his old wife, and getting a little fun out of his grandchildren, while more seriously preparing himself to anchor safely in Heaven’s harbor. Black Tam’s whiskers were now as white as “the border of an auld wife’s mutch [i.e., a close-fitting cap],” and his head was as bald as the truck of the mainmast. But he wore a wig, a good black wig with a fair sprinkling of grey in it. His face had not now the swarth hue that helped to earn him his kenspeckle [i.e., easily recognizable] name. The rough weather he had encountered for half a century had tanned it certainly, but the strong drink that he had swallowed in copious draughts, in season and out of season, with reason and without reason, had imparted so glowing a brightness to it that, when seen through a room full of tobacco smoke, it looked like the sun rising through the morning mist, round and ruddy. In the centre shone the nose, much enlarged, and with the fierce glow of a red hot coal. The Jean had been to Helsingfors this trip, but Tam had called with her at all the chief ports on the Baltic, and had had merry drinking bouts with all his old friends in each. He had taken more than three weeks to make his way from Helsinsfors to Christiansand, his last port of call, in the south of Norway, and all the while he had scarcely ever been sober, yet never thoroughly “fou” [blootered or paralytic] - for he was a well-seasoned cask. The mate, Jack Swan, was his own son-in-law, and was to command the Jean after this voyage. Indeed, he was actually in command then; for Black Tam introduced him as his successor at the various ports, and left the conducting of the business and managing of the ship wholly in his hands. With the exception of these introductions, the captain's sole business during this round seemed to be to have a rollicking holiday, of which the chief enjoyment was drinking—drinking with those with whom he had often tippled before, but with whom he would, in all probability, never clink glasses again. During these weeks, as during all his years as master mariner, no kind of strong drink came wrong to him. Lager beer, gin, Rhine wine, rum, schnapps, French brandy, Russian vodka, Scotch whisky, were all acceptable and accepted. At all ports, during this his last call, Charlie Carmichael, the cabin boy, a smart little nipper, kept his eye on him, and reported to Swan where he had cast anchor, and the mate, giving him ample time, would call in and get him away and on board in good condition for a watch below. If business there was over, the schooner would be cleared out of that port and sail made for the next. At Christiansand he had the merriest and severest bout of all with Skipsreder* [= ship owner] Kirsebom, Kornhandler [= corn dealer] Kallevig*, and Bager [= baker] Preus. With these three Black Tam made a furious, fuddling foursome. [* misspelled “Skibsreder” and “Kallenig” in original] When Swan arrived at the quiet Vertshus [= inn] to which they had betaken themselves, he found the four in a most mellow condition. They must drink a bumper to the new skipper, and another one in honor of the old one, who then drank farewell to his old cronies - the shipowner, the corn dealer, and the baker, in succession. Then “en stort Glas” (Danish for “one large glass”) or jorum (= a jug of punch) was swallowed by all, as a final bon voyage was wished.  Swan knew that he had as much as he could carry. Black Tam was not blessed with that knowledge. Charlie, the little nipper, with a lantern, showed the way to the vessel's side. The second mate came to the aid of the first and the insensible captain was speedily across the gangway, and soon safe in his bunk with coat and boots off and cravat loose. The wind was favorable, though rather fresh to start from a safe haven with. If Swan, and for the matter of that the crew generally, had not been, "rather fresh," too, this would have been noticed. When fairly out of harbor, it was observed, and, to avoid the full force of the gale, the mate hugged the coast rather closely, with the result that the schooner struck, but not with great force, on the outer end of a reef of rocks, just before passing the Naze [a Norwegian peninsula protruding into the North Sea, west of Kristiansand, not be confused with the Naze in Essex, England]. It was considered that no damage was done and the ship held on her way. When daylight came, however, it was soon discovered that the ship had sprung a leak and water was fast pouring in. The pumps were manned, and though the gale had somewhat abated, the Jean ran before the wind, with foresail -only, at fully 12 knots an hour in spite of her increasing depth in the water. Swan's great anxiety was lest Black Tam should realize her condition before he could reach land or port, or get the water so reduced that, with a fair wind, there would be little danger. His difficulties were not lessened by a heavy fog — the eastern haar (= cold sea fog) — that had begun to drift over the sea. When Black Tam's voice was heard in mid-forenoon, Swan ran down to the cabin at once, and gave him a double strong cup for his “morning” and had the satisfaction of seeing him drop off to sleep again. He put the nipper on the watch, with orders to give the captain whatever he should ask for. Black Tam thus, on his last voyage across the North Sea, was drunk the whole time. Only on the morning of the second day, he jumped out of bed, and by that time the water was over his ankles in the cabin. He was then dimly aware that something was wrong, and steadied himself to get up the companion hatchway. His wig tumbled off, but he went on deck without it. The cool morning air playing round his lockless scalp refreshed him and helped to restore him a little to his sober senses.

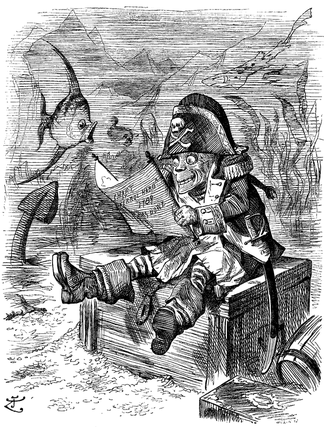

Swan hurried to him and tried to explain the whole catastrophe. But Tam's sobriety was but momentary. Feeling something wrong with his head, he muttered either “Dash my wig!” or “Fetch my wig.” Swan took it for the latter, and sent Charlie into the cabin for it. Charlie returned quickly enough but without the wig. “I say, Mr Swan,” he exclaimed, “we must be near land! There's a mavis [small bird, a Song Thrush] in its nest soomin' [= swimming] on the water in the cabin. An' the captain's wig's no in his bunk. Come doon [= down] an' see for yoursel', sir." The mate had been watching the captain lapsing into insensibility again as he sank on deck by the companion hatch, and he felt certain qualms of conscience for his share in the cause of his condition. However, he followed Charlie down into the cabin, and there indeed he saw what might easily, in the dull light there, be taken for a thrush swimming in its nest. When, however, he approached and bent to seize it, the mavis turned out to be a rat which took to the water, and the nest was the captain's wig. Switching the water out of it as he returned to the captain, he placed it damp as it was upon his head. The coolness refreshed him again and he asked for some brandy. Swan went for it, and when he returned there was a disturbance on deck, the second mate talking sharply to Charlie, some of the men growling and Charlie trying to suppress a laugh. ‘The nipper’ had been telling them all about the mavis in its nest, and when he saw the ghost of a smile on some of their faces he gave utterance to an idea that he seemed to be choking with. What he said brought back all their fears, but had a grotesqueness about it that fairly overcame the second mate's temper. He gave the lad a smart box on the ear that sent him sprawling on the deck. There the mate found him sitting when he had administered the refresher to Black Tam and had laid him comfortably on the deck. Charlie was holding his face in his hands to hide his mouth not his grief, and Swan said to him, sharply, “What is it, my boy?” Charlie thinking that he, too, wanted to know what was laughable to him, said, amidst his paroxysms: “I was wonderin' if, when we a' get droned [= drowned], the captain's nose would bizz [onomatopoeic verb, imitating the sound] the water,” and he burst into a roar of laughter, and got a kick from Swan for his impudence. The mate could not help a quiet smile passing over his own countenance. He could not settle down to the despair that had weighed upon them all just before the Captain came on deck. He went to take note of how the water was gaining, and saw that it had not risen since they had stopped pumping, and he cried out: “The water's not rising any more, lads. Let's have another turn at the pump. Who knows but we may get safe ashore yet? — Get us something to eat and drink, Charlie.” Charlie brought them some bread and cheese and a pannikin of grog [small cup of rum] a-piece and they all set too with a will, and were glad to see that they were 'lightening' the schooner. While they were all busy working for their lives they had not noticed that the fog was lifting, until Charlie cried: “There's Dysart Woods, an' yonder's Ravenscraig. We'll be in Kirkcaldy dry dock in half an hour.” The crew looked round as if in a dream, and saw that he was right. With glad cries and tears in their eyes, they stopped their labor at the pump, trimmed the sails, and generally pub things shipshape for entering harbor. Black Tam was assisted to the cabin, where he remained till a cab came along from the George and took him quietly home. When overhauling the schooner's bottom in search of the leak, it was found that a large cod had been drawn into the hole, and had lasted just long enough to serve their purpose. The crew often afterwards laughed over Charlie's wonder about Black Tam's nose." ConclusionPutting the humour to one side, what does this account tell us? From a family history point of view it is clear that 'Black Tam' is an old man and that his wife, (subsequently proved to be Agnes Hay) was still alive at the time. The probate record of his son Robert, would indicate that Tam had passed away before 1827 as no mention of him is made within the document. Tam's daughter Margaret was married to James 'Jack' Swan at the time both documents were written, and confirmation of their marriage would narrow the potential date of their salvation by 'cod' still further. Initial research would suggest Tam's date of birth to be around the early 1750's, which will perhaps enable further research into even earlier generations. The article is also packed with social and economic history. Trade routes to the Baltic are described, as are the type of goods being shipped back to the east coast of Scotland. The type of ships being used, a glimpse of life on board, and the weather - brisk winds and the sea 'haar' that we on the east coast of Britain are so familiar with, add colour and atmosphere. To return to the present, Philip and I are of the opinion that although Black Tam's descendants are now spread around the globe, (Philip lives in St Louis, Missouri), there may still be #Berwick descendants alive and kicking in Fife. If you think you may be one of them we would love to hear from you!

4 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy