|

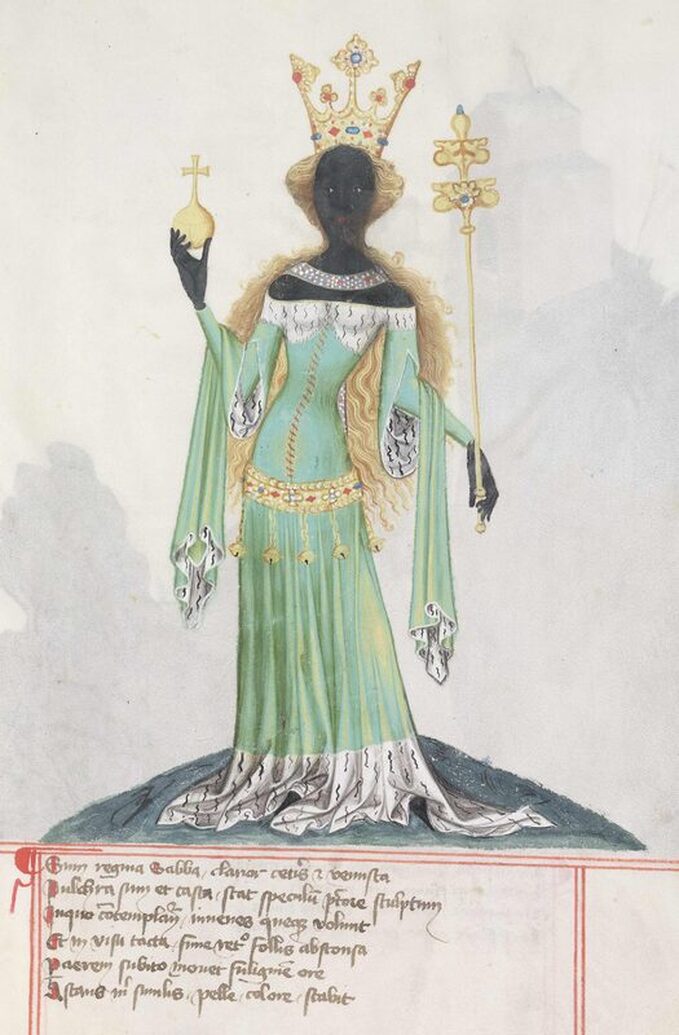

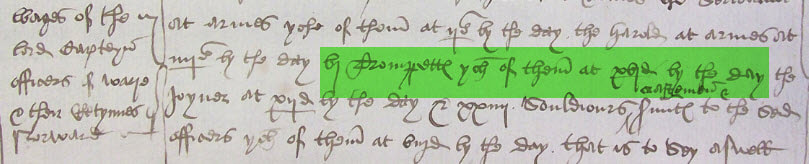

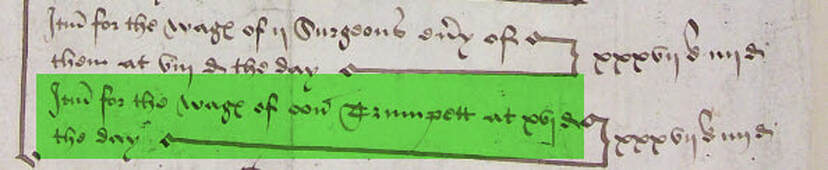

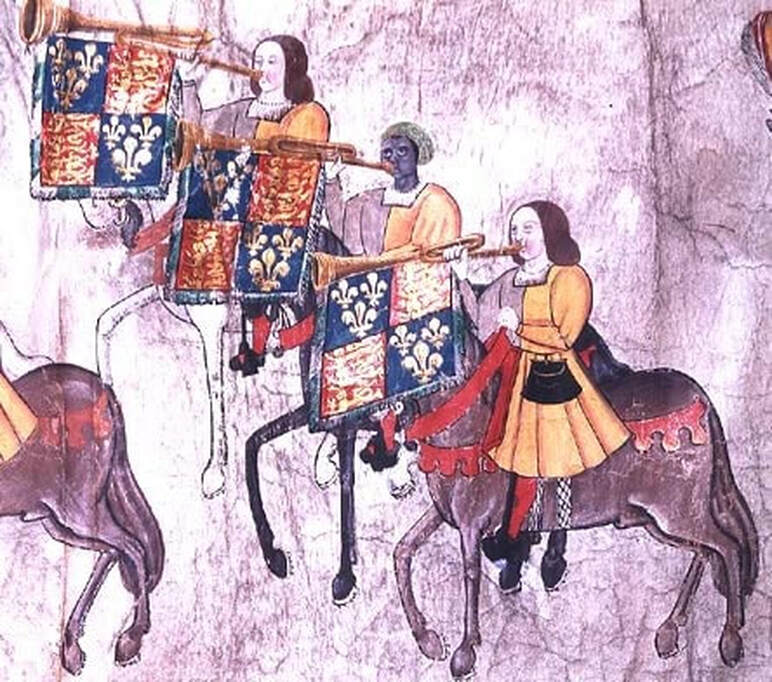

October’s blog is inspired by both ‘Black History Month’ and references I encountered earlier this year whilst looking for some inspiration for a piece of fiction. I had been digging about in Historic Environment Scotland’s, medieval document research for Edinburgh Castle when entries relating to two ‘Moorish Lassies’, and the ‘Black Lady Tournaments’ of 1507 and 1508 had rather piqued my interest. The ‘Lassies’ are believed to have arrived by ship into Edinburgh, rather disturbingly, with a load of exotic animals, an African Drummer and other black individuals in 1504. Whilst Columbus had discovered the ‘Americas;’ in 1492 and the Portuguese were engaged in the slave trade by this time, neither England nor Scotland were actively involved in the trafficking of human cargo at this early date. As Church registers were yet to be introduced (1538 in England, 1553 in Scotland) these documents afford a rare glimpse into the lives of black people in Britain during the early sixteenth century. It is thought the ‘Lassies’ and other individuals may have been aboard a Portuguese Ship, captured by the Scottish High Admiral and Privateer, Andrew Barton, revenge for whose death at the hand of the Howards in 1511, is often recounted amongst the reasons for the Battle of Flodden in 1513. War by sea between England and Scotland was soon followed by war by land, and in the letter of remonstrance and defiance to Henry VIII., with which James preceded the invasion of England, the unjust slaughter of Andrew Barton, and the capture of his ships, were stated among the principal grievances for which redress was thus sought. Even when battle was at hand, also, Lord Thomas Howard sent a message to the Scottish king, boasting of his share in the death of Barton, whom he persisted in calling a pirate, and adding that he was ready to justify the deed in the vanguard, where his command lay, and where he meant to show as little mercy as he expected to receive. And then succeeded the battle of Flodden, in which James and the best of the Scottish nobility fell; and after Flodden, a loss occurred which Barton would rather have died than witnessed.[1] The Moorish Lassies and the Black Lady Tournaments The ‘Moorish Lassies’, and their fellow African passengers far from being slaves, were readily accepted into the Court of James IV and thereafter formed part of the Royal entourage. The ‘lassies’ who were called Margaret and Ellen were appointed as Ladies in Waiting to Margaret Stewart, the illegitimate daughter of James IV and Margaret Drummond, thought to have been born circa 1495. These were undoubtedly privileged positions within the young Margaret’s ‘royal’ household. She and her African ladies made a tour of the Borders on horseback in the autumn of 1504, where one of them is rumoured to have been baptised. As to the Black Lady Tournaments, there has been much speculation as to the role played by the two African girls, with some sources maintaining Ellen played the lead as the ‘Black Lady’, to James IV’s ‘Black Knight’. Others consider the girls acted in supporting roles as hand maidens to James’ daughter Margaret who herself played the female lead. There is also speculations that role was played by a gypsy woman ‘whose portrait survives among the collection derived from Piers the Painter (Andrea Thomas, Princelie Majestie: The Court of James V of Scotland (Edinburgh, 2005), p 83).’ A doubt about the genuiness of the Black Lady’s ‘African’ identity is raised by the black chamois sleeves which she wore as part of her costume. These were conventionally used as part of the Renaissance ‘blackface’ disguise in court masques. It is credible that they could also be worn for the purpose of modesty and warmth by a genuine African in the Scottish weather… The role might have been played by two separate people in the two different years and could even have been played by a man. Nor do the record of the tournament expenses give up the secrets – the documents maintain the illusion, recording the outlay on the clothes of the Black Lady, just as they do when recording payments for the unicorn pulling her chariot.[2] On both occasions the description of the costume worn by the ‘Black Knight’ would appear to have been a far departure from the traditional plate tournament armour, prompting some to hypothesise it was the King dressed as an African warrior or Ottoman nobleman of whom he may have learned from the ‘Moors’ at his court. The colourful pageantry of the tournament also included: Dragons, a unicorn and other unlikely animals … They may also have included animals from the Royal Menagerie which at this time included a lion and a wolf. [3] (The report and research undertaken by Historic Environment Scotland is available online as a pdf document and can be downloaded here) In terms of establishing the presence and roles of black individuals in Britain in the period before slavery, in my opinion there are two books that provide some very enlightening evidence. The first is Peter Fryer’s ‘Staying Power’ whose dramatic opening statement to Chapter 1 ‘There were Africans in Britain before the English came here’ cannot fail to garner curiosity, and the second is Dr Miranda Kaufmann’s ‘Black Tudors’, which given my own geekish fascination in the Borderlands in the early sixteenth century, reintroduced me to a certain John Blanke, a chap I had met before but through a palaeography exercise rather than the fact of him having been black! African Soldiers at Hadrian’s Wall Peter Fryer brilliantly positions himself to tell the story of ‘Blacks in Britain’ by beginning with evidence of African soldiers that served with the Roman Army and a division of Moors stationed at Hadrian’s Wall in the 3rd century AD. He further recounts the evidence of a certain ‘Ethiopian’ who dared mock the Libya born Emperor Septimus Severus in 210 AD near Carlisle. Having returned from a successful foray against the inhabitants north of the wall, Fryer tells us the emperor was less than impressed to ‘encounter a black soldier flourishing a garland of cypress boughs.’ To a Roman, the Cypress was an omen of death …, but I shan’t spoil the outcome of that particular tale and shall leave it to be read alongside the rest of Fryer’s fascinating book.  (Cropped) The national archives describe this thus: "an extract from the 60ft-long Westminster Tournament Roll, shows six trumpeters, one of whom is Black and is almost certainly John Blanke. All the trumpeters are wearing yellow and grey, with blue purses at their waists. John Blanke is the only one wearing a brown turban latticed with yellow. He is mounted on a grey horse with a black harness." Date 1511. Wiki Commons John White the Black Tudor Trumpeter Dr Kaufmann’s publication is another gem, presenting as it does the story of 10 separate individuals the lives of whom, colour aside, would normally be passed over. As such it covers aspects of Tudor history that are a far departure from other offerings covering a similar period. Her opening chapter focuses on John Blanke (John White) a black trumpeter who first appears in 1507 being paid his wages of eight old pence (8d) per day by Henry VII. Kaufmann has done her research, digging in other records to find comparative rates for other court ‘tumpeters’, presumably to establish whether his rate was in anyway compromised on account of his colour. Crucially, she finds not. From my diggings into accounts surrounding the Battle of Flodden in 1513, it is interesting to note that John is paid at the rate of a mounted soldier, 2d more than soldier on foot, and the soldiers, mariners and gunners that arrived at Newcastle by ship with the Lord High Admiral. It is also interesting to note that at 8d, his rate is half that of the vj Tromppett[es] ych of them at xvj d by the day [6 Trumpeters each of them at 16d by the day] detailed in E 101/56/27, the Accounts of Sir Philip Tylney in 1513, and It[e]m for the wag[es] of oon Trumpett at xvj d the day [Item for the wages of one Trumpeter at 16d the day] detailed in the ‘E36/1 The Accounts of Edward Benstead’, a year earlier in 1512. At the death of Henry VII and accession of Henry VIII in 1509, John Blanke successfully petitioned the new King for a pay rise, where his wages were brought in line with those known to have accompanied the troops northwards. He married in January 1512, although to whom is not known, and the record of the gift made by the King at his wedding is the last record Kauffman has found of Blanke in the royal records in the records. He does not appear amongst the next list of named trumpeters recorded January 1514 … could it possibly be? In all probability if Blanke had indeed accompanied the army anywhere it would have been with the King to France, rather than with the Earl of Surrey to a soggy field in Northumberland! Sir Pedro Negro and Lady Marion Hume in 1548/9 Indulging in some highly scientific research of my own within the State Papers Online i.e. entering the search term ‘negro’, returned a further interesting reference to an individual with connections to the Border region. This time it refers to a Spanish mercenary in the employ of Henry VIII during cross border hostilities known as the Rough Wooing (1543 – 1551) by the name of Sir Pedro/Petro Negro. Dr Kauffman again picks up the trail and eloquently debates the question of the colour of his skin in an online article on her website. The evidence she finds in favour of his having been black is contained in ‘a letter written in 1549 by Marion, Lady Home’ widow of George, 4th Lord Home of Hume Castle. … she is complaining about the villainy of the English who ‘dystrow all this cuntre’. Strangely it seems the Spaniards, and ‘the Mour’ behave better, ‘lyk noble men’. They owe money to the ‘pur wyfis in this toun for ther expenssis’. It seems then, that the English and Spanish, who had been at Haddington, passed through Hume on 19 March, and were billeted there, leaving debts. Yet, Lady Hume seems to show special favour to the Spaniards, and especially the Moor, urging Guise to be ‘gud prenssis’ to them. Perhaps her favour was won the year before, when the Spaniards were involved in a failed attempt to take Hume castle from the English. 'Egyptians' in Northumberland and the Scottish BordersWhilst this does indeed makes fascinating reading, it is important not to lose sight of another group of people who became synonymous with Northumberland and the Scottish Borders – the ‘Eygptians’ more commonly known simply as ‘gypsies’ and often referred to locally as ‘muggers’ (potters, rather than pick-pockets!). Whilst they make only the briefest appearance here they too were known to have been in the area during the early 16th century. The first undoubted record referring to Gypsies in Great Britain is :—' 1505, April 22. Item to the Egyptianis be the Kingis command, vij lib.' "[5] This extract is a quote from the Account of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland during the reign of James IV. By the mid-19th century there seems to have been some debate over their ethnic origins, colour of their skin and other and other traits. The special opinion of him as an Egyptian, or one of a different breed from the other inhabitants of this and, must be established; and this proceeding on those noted and peculiar circumstances of manner and appearance by which, in all countries that they have visited, this loose and lazy race have so remarkably been distinguished. Among these are the black eye and swarthy complexion ; a peculiar language or gibberish, intelligible only to themselves …[6] There are many other such descriptions intermingled with evidence in equal measure that some ‘gypsy’ families were both fair haired and fair skinned. The Borders aside, records of gypsies in Scotland date back as far as 1462 with ‘Saracens’ noted in Galloway, with some sources attributing them as the origin of the traditional Morris or ‘Moorish’ Dancing. Although written over 100 years ago David MacRitchie’s book ‘Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts’ makes interesting reading and provides an alternative account to those of the English Tudor Court. Useful Links [1] Significant Scots, Andrew Barton, Electric Scotland

https://electricscotland.com/history/other/barton_andrew.htm [2] Historic Environment Scotland, Edinburgh Castle Research, The Medieval Documents, 2018 [3] Historic Environment Scotland, Edinburgh Castle Research, The Medieval Documents, 2018 [4] Miranda Kauffman http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/pedro-negro.html [5] David MacRitchie, Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts, Edinburgh, 1894. https://electricscotland.com/history/gipsies/scottishgypsies2.pdf [6] Hume's Commentaries on the Law of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1844, vol. i. pp. 474, 475. https://electricscotland.com/history/gipsies/scottishgypsies2.pdf page 2. For those of you who like digging about in old manuscripts but can't access the State Papers Online, a fabulous website The Tudor Chamber Books of Henry VII and Henry VIII containing transcriptions of manuscripts dating from 1485 - 1521 is available online at: www.tudorchamberbooks.org/

1 Comment

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy