|

‘Tithes’ – nearly everyone has heard of this historic form of taxation and associates them to with payments to the Church, but what exactly were tithes and why are their records so valuable to historical research? A ‘tithe’, literally meaning one tenth, at the inception of the tithing system in the 6th – 8th centuries, was essentially a tax on agriculture originally designed to benefit the established church and the clergy. Unlike other forms of taxation tithes were a burden born solely by those whose income arose from agriculture and the land, either directly, or indirectly. Before being commuted to a monetary equivalent by the Commutation Act of 1836, tithes were often paid in kind. They were based on ‘one tenth’ of the natural gain of a crop, herd or flock. They were, however, imposed on the gross product, with no allowance taken or made for seed sown, fertiliser or land improvement. By 1836, the method of collecting tithes in kind had become outdated and was no longer fit for purpose. The decision was made to abolish the ‘in kind’ system and replace it with equivalent monetary payments or ‘rentcharge’. (In Scotland, where Tithes were known as Tiends, a form of commutation had been introduced in 1663. Therefore, they were not included in the surveys or maps produced as a result of English reforms of 1836.) In truth, however, like anything that has been around for almost a thousand years, the ‘story’ of tithes before they were commuted to monetary payments in 1836, is rather more complex than it first appears As so often seems to be the case, those at the ‘top’ stood to gain far more from tithes than those at the ‘bottom’! But what exactly was subject to tithe payments and just who was entitled to what? Tithes could be subject to some degree of manipulation and regional variation according to land use, and, like some manorial customs, what was liable to be ‘tithed’ varied from parish to parish. Nonetheless tithes fell into three classifications; predial, mixed and personal. Classifications of TithesPredial Tithes These related to the ‘fruits of the earth’, so anything that grew in it, or from it, such as corn, hay and other crops. It also often included wood. These were the most valuable class of tithes. Mixed Tithes Mixed Tithes related largely to animals such as lambs, calves, colts, or to animal products such as wool, milk, eggs etc. Personal Tithes These tithes were payable on the gains of labour in related agricultural industries such as corn milling or fishing. Tithes were grouped further into Great Tithes and Small or Lesser Tithes: Great Tithes were paid to the Rector (administrative leader) of a parish, who may be a resident incumbent i.e. bishop, prior, prioress or an establishment such as a monastery, nunnery, college etc. These comprised the most valuable Predial Tithes or Corn Tithes. Lesser or Small Tithes were paid to the Vicar appointed to a parish and performing a parochial service. These tithes were drawn from the Mixed Tithes, so lamb, wool, eggs etc. Tithe Collection & SatireBefore the ‘Commutation Act of 1836’ when payments in kind were replaced by a monetary equivalent or rent charge, it was the means in which Tithes were collected and paid that many found so repugnant. Great tithes or corn tithes were often left in the field from where ‘tithe collectors’ appointed by the owner would arrange collection and/or sale. The recipient of the Lesser Tithes was also perfectly entitled and within their rights to enter a farm or property at any time to collect their dues. This custom naturally lent itself to satire, with the local ‘incumbent’ often the butt of the joke.

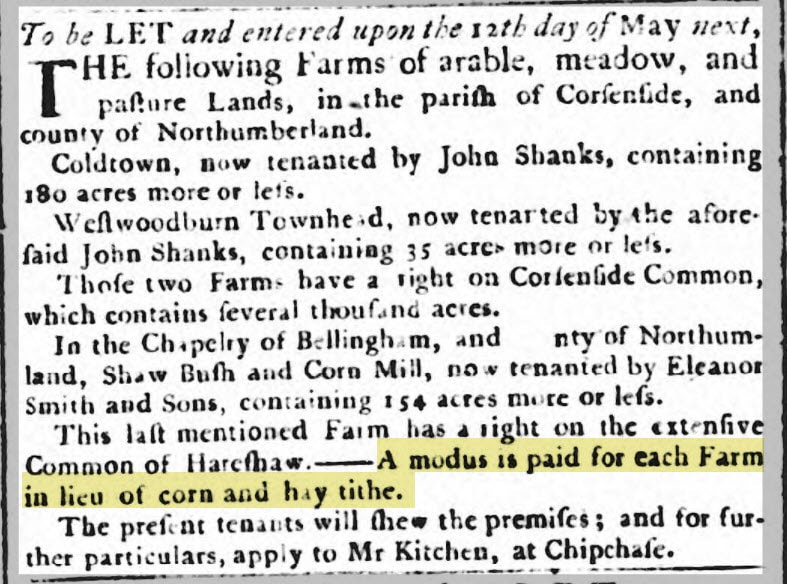

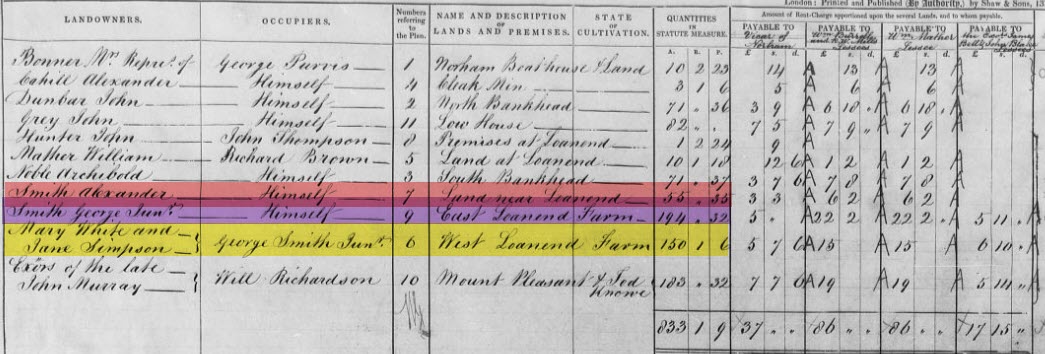

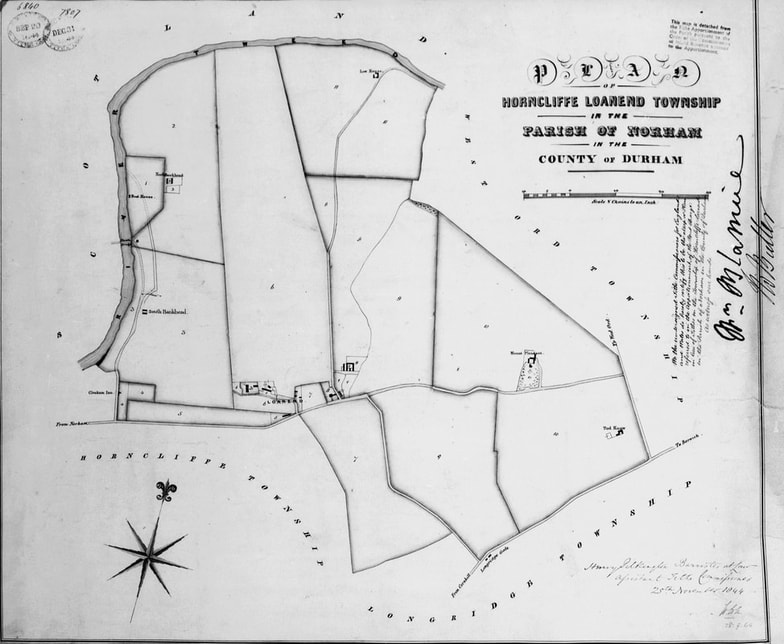

As a clergyman’s daughter, author Jane Austen was extremely familiar with the English tithe system and the topic of a clergyman’s ‘living’ often appears in her novels. Her obsequious character ‘Mr Collins’ in Pride and Prejudice ranked "making such an agreement for tythes as may be beneficial to himself and not offensive to his patron" his first and foremost duty as a clergyman. As a rector, like Jane’s father, her character was entitled to both the Great and Lesser Tithes of the parish, and to their collection. Humour aside, the payment and collection of tithes, particularly those made in kind has been described as a ‘vexatious impost’ and formed the root cause of many a dispute. However, tithes were not designed to be contentious, but more as a means of bringing communities together. In writing about the significance of Tithes during the eighteenth century, Daniel Cummins argues Although tithes could cause contention and friction, their real significance lies in the numerous relationships they created within eighteenth-century English society. These relationships constituted some of the most important everyday economic, contractual and social connections between individuals and were a central feature of parochial life during this period.[1] Impropriation & Impropriators In reality, however, the reformation and dissolution of the monasteries saw much Tithe entitlement pass from the church, to the Crown and from there into the hands of laymen (impropriators), in a process known as impropriation.[2] It has been estimated that in the period post-1530 up to one third of all great tithes were in the ownership of laymen. Furthermore, great tithes could be traded, i.e. bought, sold or leased by both the church and layman owners. … tithe purchase involved an agreement made before harvest. The tithe purchaser entered into a contract with the tithe owner by which he or she agreed to pay a certain sum for the bought tithes on appointed days. Tithes sold in this way made up a significant portion of all the grain which reached the market.[3] It is thought that by the time the Commutation Act was passed in 1836, 25% of the value of all tithes was in ownership outside the church. Tithe Records for Historical Study Tithes records are essential for the comparative study of acreages farmed, land use, cropping patterns, yields and crop values throughout history which is also helped by the uniformity of the ways in which the data was collected and compiled. I myself drew on the analysis of tithe data from Durham Cathedral Priory Muniments for evidence relating to corn production in the North East at the time of the Battle of Flodden in 1513.[4] For the Family Historian, however, the records and maps generated as a direct result of the 1836 reforms are of particular interest. Composition and ModusPayments in kind had been abolished in many areas before the reforms of 1836. Those made in monetary equivalents before 1836 came in two forms; a ‘composition’ which was subject to periodic revision, or termination by either party or a ‘modus’ which was a permanent charge attached to a particular product or piece of land. Where payments in kind persisted at apportionment, or had already been commuted to compositions or other monetary equivalents, specific details can often be found in the accompanying Articles of Agreement to the 1836 revisions. The records generated by the reforms produced, a map, an apportionment schedule and a file between the years 1841 and 1860. These records were also produced in triplicate: an original and two copies of every confirmed instrument of apportionment. The originals are now in The National Archives. The two copies were deposited with the registrar of the diocese and with the incumbents of and churchwardens of the parish. In many cases the copies and subsequent altered apportionments are now deposited in the relevant local record office.[5] The Genealogist & Tithe Records OnlineThe good news is that for those with access to the internet the records are also available online (along with other record sources unique to the site) with a diamond subscription to ‘The Genealogist’. Furthermore, the records can be searched by place, not just by person, so if your interest happens to be in a particular farm, village or town the tithe data provides a fascinating snapshot in time. Examples and snippets relating to Horncliffe & Norham Mains. As examples of the type of information that can be sourced from tithe records, here are a few snippets that I found useful in the course of research into my own family. It was already known from the records that over the years the Smith family had interests, both owned and tenanted in several farms around Horncliffe and Norham, most notably Loanend, however the information lacked specifics. The tithe schedule dated 1844 for Horncliffe provided the following information:

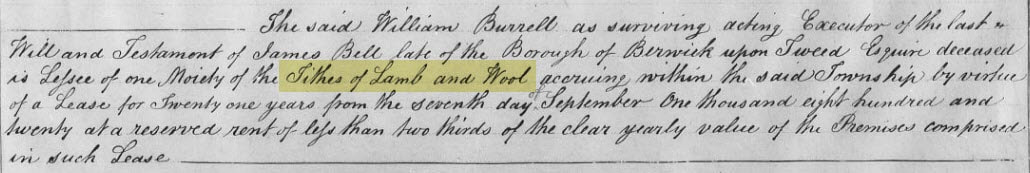

Accompanying Tithe Map from the 1844 Survey of Horncliffe Loanend. Reproduced courtesy of The Genealogist and The National Archives, Kew. Tithe Maps such as these are accessible online, along with many other unique record sources with a subscription to 'The Genealogist' https://www.thegenealogist.co.uk/ The land ‘owned’ and occupied by George Smith jnr at Horncliffe is represented on the accompanying map by the number ‘9’, and the land he occupied which was rented from his wife’s relatives by the number 6. (NB. It is more usual to see land owned and occupied represented by a series of numbers, not just one, with the land use of each parcel also given.) The Articles of Agreement relating to the apportion of tithes make fascinating reading too and are packed with additional information and local idiosyncrasies. Those arising from a meeting which took place on the 17th August 1839, relating to Horncliffe confirm that prior to the 1836 reform, Small Tithes with the exception of Lamb and Wool, which were leased from the Dean & Chapter of Durham by the Executors of James Bell of Berwick upon Tweed decd, had still been payable in kind. A modus of ‘one shilling’ had been in place as payable in lieu of hay tithes. Similarly, the ‘Articles of Agreement’ relating to the Tithes in the Township of Norham Mains confirm that payments had still be made in kind there too – both Great and Small, except the following for which ‘customary’ payments had been made as follows:

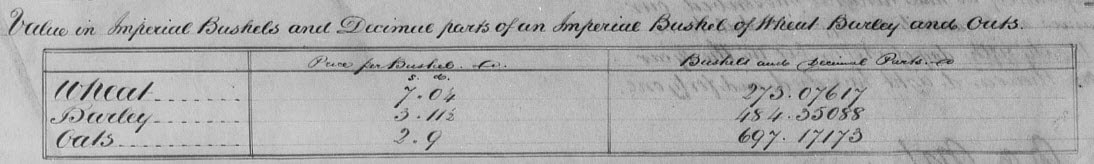

There is even more historical information which can be extracted from the records relating to the commutation of Tithes, not least the values attributed to corn, given in bushels.[6] There are many taxes from which historical information can be gleaned, but none have the longevity or depth of information as Tithes. The above is a just a brief overview designed to provide background, context and an explanation of a few of the terms that are likely to be encountered during your own foray into the world of Tithes and associated information. There are many excellent books and essays on the subject of the Tithe system, a few of which are listed below. In addition 'Tithe Surveys for Historians' by Roger J.P. Kain & Hugh C. Prince, Philimore, 2000 provides an in-depth explanation and background to the information the surveys will provide. Another very helpful overview is available from Family Search at https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/England_Tithe_Records_(National_Institute) [1] Daniel Cummins, ‘The Social Significance of Tithes in Eighteenth Century England’ The English Historical Review, Vol. CXXVIII No. 534, Oxford, 2013 pp

[2] When entitlement passed to the church or religious houses it was ‘appropriated’. [3] B Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants and Production in the Medieval North-East’, Regions and Regionalism in History, Woodbridge, 2007, p.162. [4] Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants and Production in the Medieval North-East’, Regions and Regionalism in History, Woodbridge, 2007; Ben Dodds, ‘Peasants, Landlords and Production between the Tyne and the Tees, 1349-1450’, Regions and Regionalisms in History, Woodbridge, 2005. [5] The National Archives http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/legislation/other-archival-legislation/tithe-records/ [6] There were approximately 8 bushels to the quarter and 4 quarters to the avoirdupois ton which equated to 20 cwt, or 2,000lbs, = 62.5lbs per bushel.

2 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy