|

With not only a new year but a new decade on the doorstep many folks will be turning their thoughts to outlining goals and aims for their research in the coming months. Some will be considering taking a course to learn a new skill. For the researcher who is serious about digging into the past the one vital weapon to have in the armoury is the ability to read, transcribe and interpret old documents. The ‘art’ of palaeography can open many doors to the past in all fields of historical enquiry not least that of family and local history research. Too often the interpretations and findings of reputable authors and scholars who have gone before are relied upon, but dig a little deeper and it often becomes apparent that evidence is based on the same old documents regurgitated time and again. Even worse are the opinions based on evidence extracted from a summary or abstract of a document’s contents rather than the document itself. This became glaringly apparent to me during the research phase of my Master’s dissertation – so much vital evidence had been overlooked as the document that formed the basis of my thesis had clearly not been read or analysed before. It may seem daunting when first presented with a page of seemingly illegible scrawl, but do not be put off by it. You do not need any specialist skills, equipment or an intellect the size of a planet to be able to decipher old handwriting, just practice, a pencil, a magnifying glass and more often than not, a good deal of patience. There are or course a few simple rules: Firstly, get to know your document – Familiarising yourself with the type of document you are transcribing will enable you to:

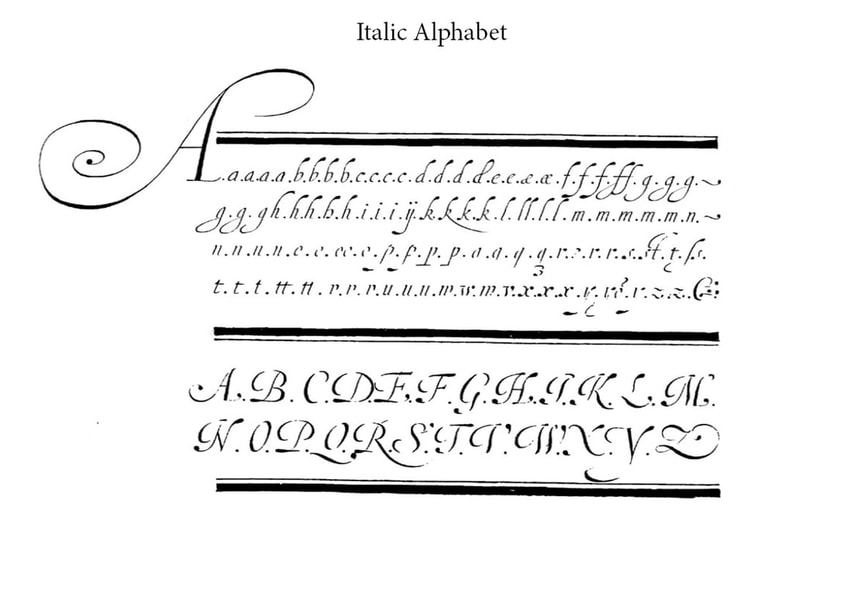

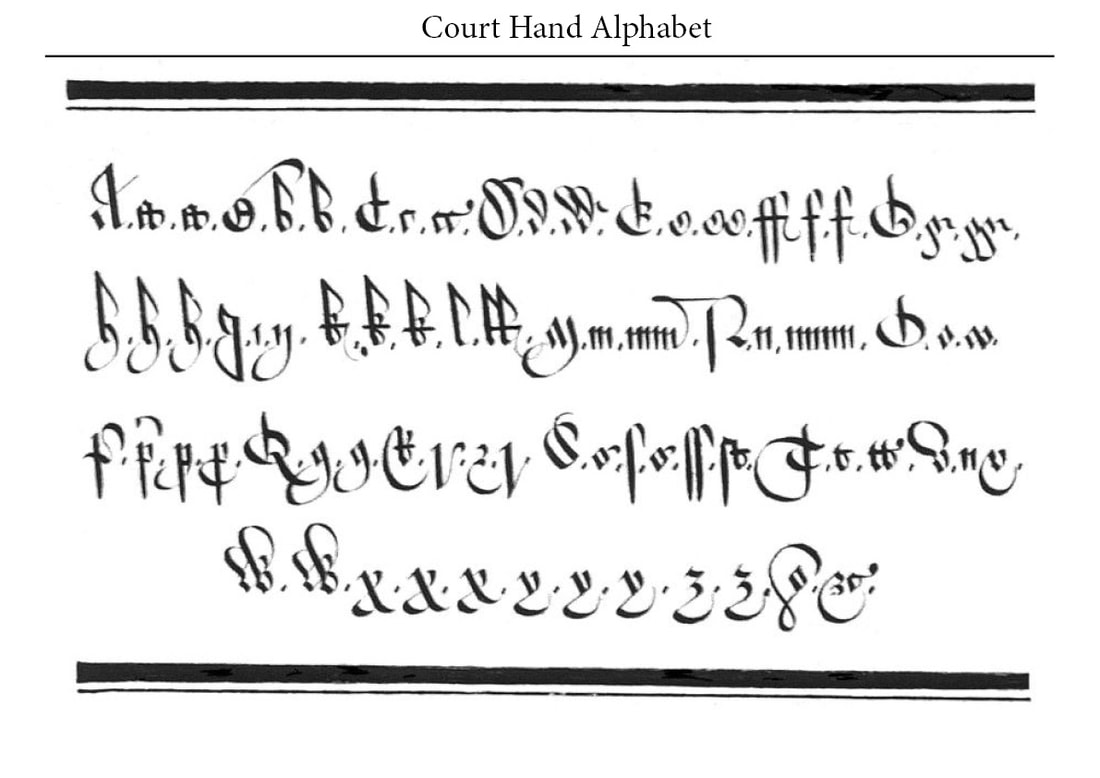

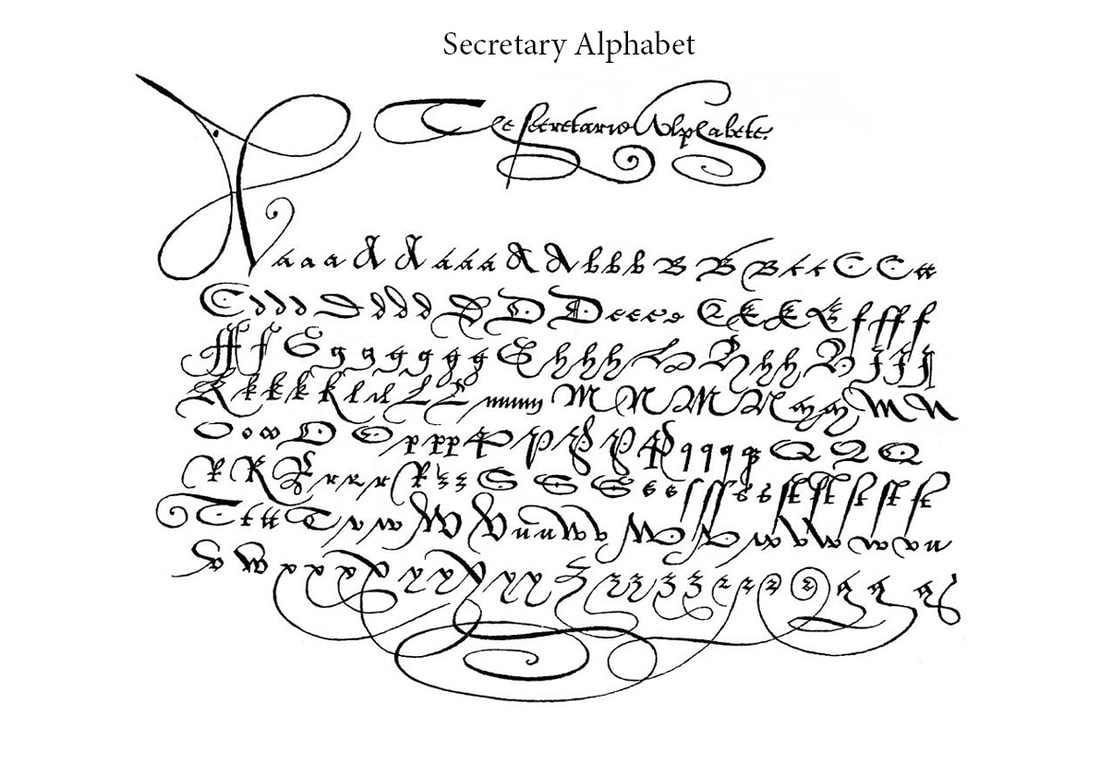

Different Hands and Letter FormsAlthough English and Scots were the spoken word, the language of written documents before the advent of the early modern period at the beginning of 16th century was Latin. From this point forward English and Scots gradually crept into common usage in written records. Different hands (styles of writing) were used for specific purposes and those most likely to be encountered and prove the most problematic, date from the 16th, 17th & 18th centuries. They are:

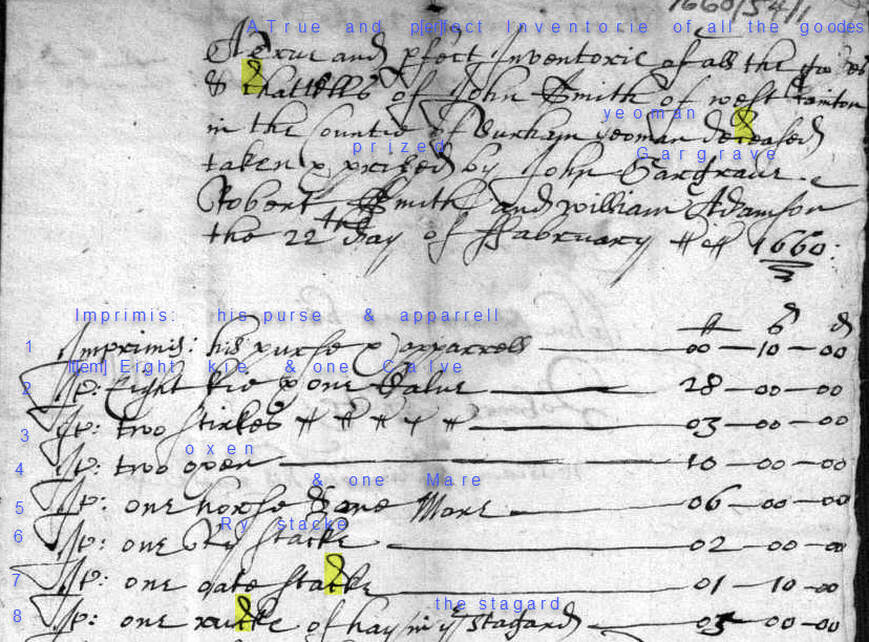

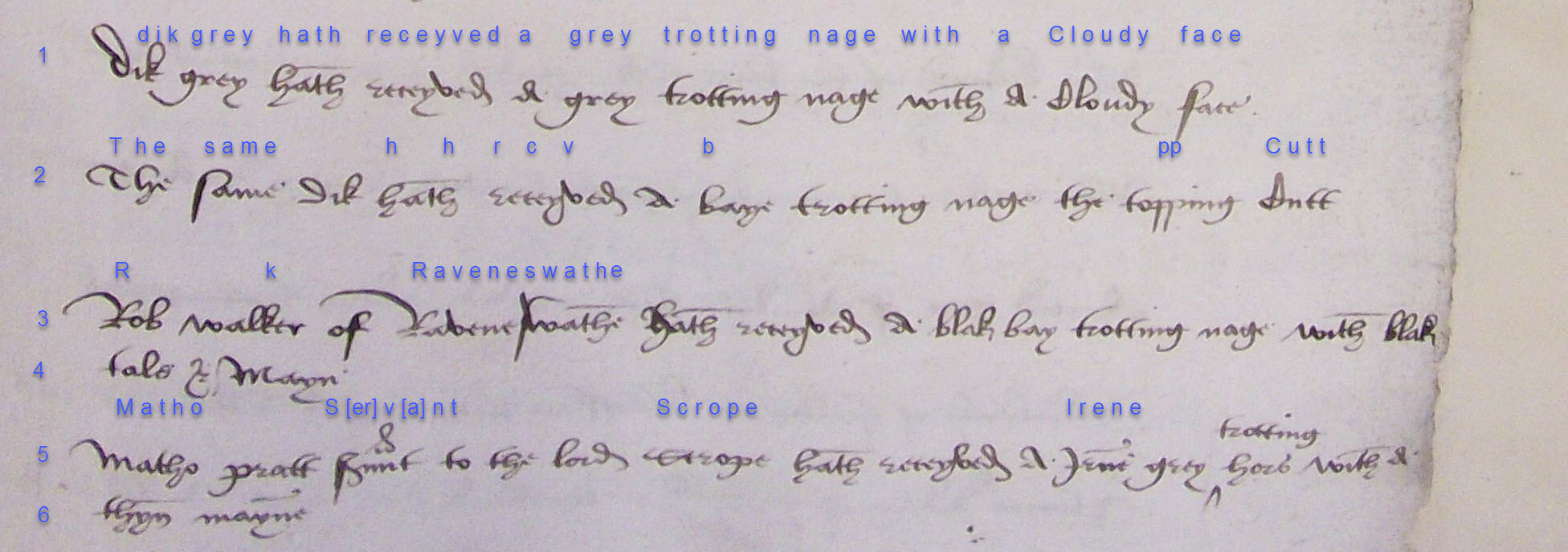

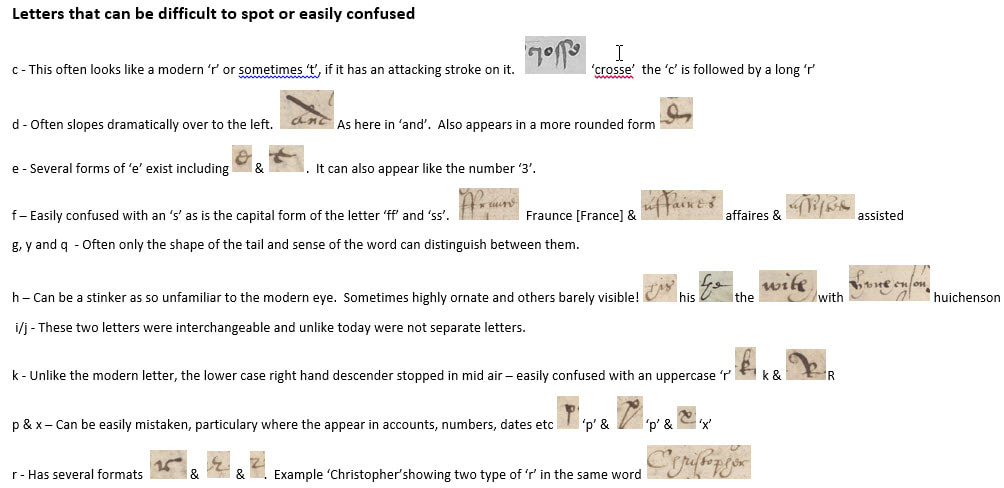

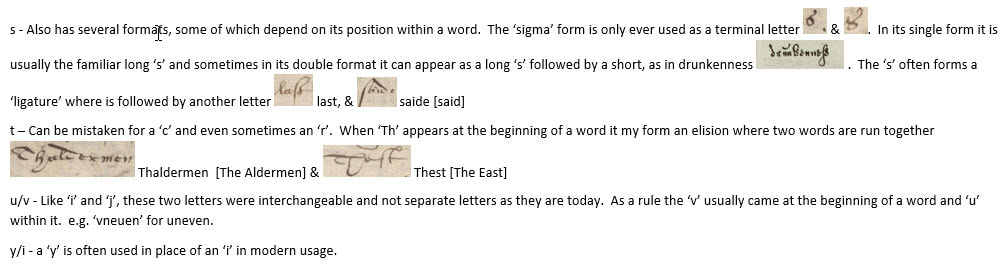

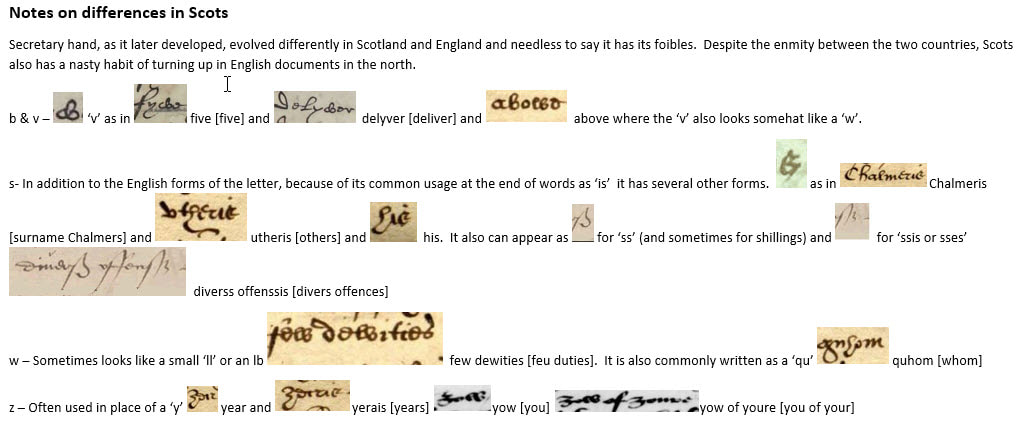

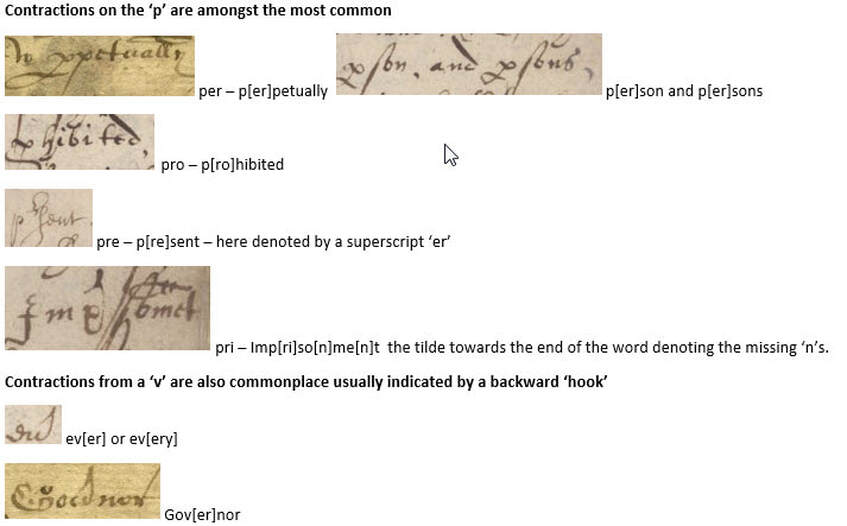

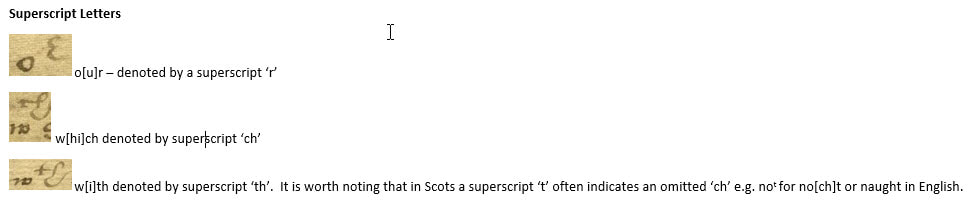

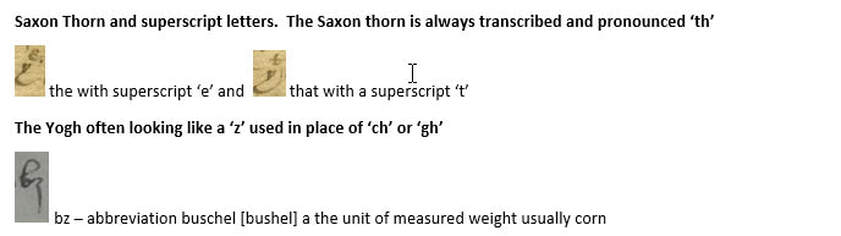

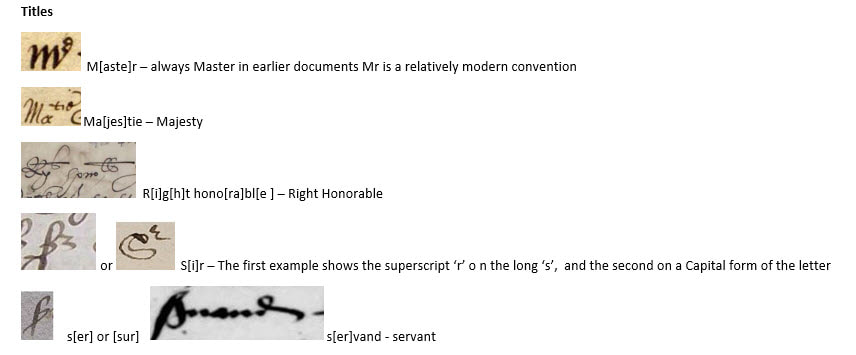

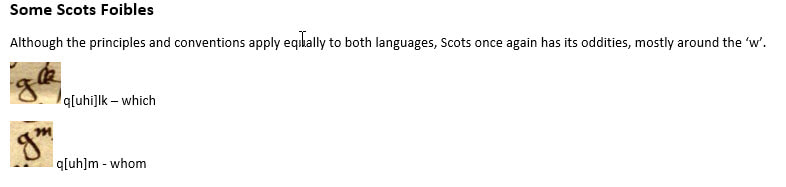

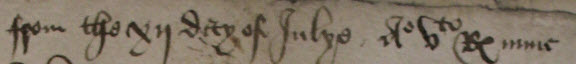

A few basic transcription Hints & Tips 1. The document, whatever and whenever it may be, is ALWAYS your key!!! It is important to remember that, then as now, people’s hands had their own personal style – but these were still based on standard letter forms and conventions which evolved over time. Start by writing out the words you DO recognise and build a ‘lexicon’ of different letter forms that appear in the document as you go. (You may also find it useful to number the lines on a COPY of the document so as not lose your place or inadvertently miss a line entirely – its easily done!) The scribe here has an unusual flourish above the letter 'c' (highlighted). His lowercase 'g's are also unusual and a particular characteristic of his hand. You will inevitably encounter words that are no longer in common usage, such as 'prized' for appraised, 'kie' for cows and 'stagard' meaning either stackyard or a temporary roof capable of elevation, and designed to protect a stack or rick of hay or grain (here I think meaning the former). Compiling a glossary of unfamiliar words and phrases as you go can prove invaluable. 2. Secretary Hand – Common letter forms, variants and conventions 3. Common Contractions, Abbreviations and Suspensions 4. Numbers, Dates and Spellings Although these do not usually cause too much difficulty there are a few points that are worth remembering. Numbers Numbers are almost always written in roman numerals in earlier documents and almost always in financial accounts. As these are easy to look up if not already familiar they are not covered in detail here. One point that does sometimes catch folks out are the numbers 1 - 4. Whilst it is perfectly normal to expect them to appear as ‘ii’ iii’ ‘iv’ etc - in written documents the terminal digit ‘j’ is used - so ‘j’ = 1, ‘ij’ =2, iij =3 and instead of ‘iv’ for 4, it appears as ‘iiij’. In the same way 14 is ‘xiiij’, 23 ‘xxiij’ & 29 ‘xxviiij’ etc. Another point of note is the use of superscript xx to mean ‘score’ or twenty, so that iij xx is common for sixty i.e 3 x 20 = 60 Dates Calendar years In England until 1752 the new year began on Lady Day or 25th March, thus the 24th March 1750 was followed by 25th March 1751. In 1752 England and America finally caught up with the rest of the world and the new year was set where it is now as 1st January. (Eleven days were also wiped from the calendar in the same year - Wednesday 2nd September 1752 was followed by Thursday 14th September 1752). In Scotland, however, the new calendar year was adopted by an act of Privy Council in 1599, so that in Scotland 31 December 1599 was followed by 1 January 1600 which conforms to modern convention. Regnal Years In the course of your forays into old documents it is likely that at some point you will encounter ‘Regnal Years’. These are measured in years from the date the Monarch ascended the throne. For Henry VIII his reign began on 22 April 1509, therefore the 5th year of his reign began on April 22 April 1513 and ended 21 April 1514. 'from the xij day Julye Ao Vto Re nunc' Henr viij (not shown) - Note the superscript ‘o’ from Latin ‘Anno’ and the ‘to’ above the V from the Latin ‘Quinto’ meaning fifth. This is also expressed as ‘th’. Reges nunc is Latin for ‘now King’. Extended it reads xij Julye A[nn]o Vto R[eg][es] nunc Henr[ey] Viii/ and translates as ‘12 July in the 5th year of the reign of Henry VIII now king’. This document was written in English but it is not uncommon to find many such documents ‘topped and tailed’ in Latin. C R Cheney (ed.), Handbook of Dates for Students of British History is extremely handy for the regnal years of Kings of England but no use for the Scottish Kings whatsoever. They can be found in Archibald H Dunbar, Scottish Kings: A Revised Chronology of Scottish History 1005-1625. The book is rare but a copy can be accessed online through archive.org at https://archive.org/stream/scottishkingsrev00dunbuoft/scottishkingsrev00dunbuoft_djvu.txt Dates in Latin It was also quite common for the dates in documents written in both English and Scots to appear in Latin e.g. 24 May 1567 would be ‘vicesimo quarto die Maij mvclxvij’ Also be aware of abbreviations for months ending ‘ber’ - so September to December. ‘9ber’ is taken from the Latin for nine or ‘novem’ and relates to November not September as the 9th month! Fortunately this little quirk is rare and more common in Scots than English Scottish ‘jaj’ Dates If transcribing Scottish documents this is one form of dating you will encounter a lot! It is much easier to think of it as what it actually is – a corrupt form of 1m or 1,000 with year numbers added with a ‘C’ at end so the year 1600 would be written jajvj C. (the jaj = 1,000 the vj C 600) or 1652 as ‘jajvj C & lij’ – note the ‘&’ after the C. Spellings It is helpful to remember there was no such thing as a dictionary of ‘all words’ much before the definitive work of Dr Johnson in 1755. Spelling was largely phonetic, and words were written as they were spoken which means a great deal of regional variation occurred. You may find it helpful to say the word out loud in your best attempt at a regional accent. Nonetheless, it is particularly important to check words in your transcription which make no sense at all - as this probably means that your solution will be wrong and you should think again! It may be that just one or two letters have been mis-transcribed even though the word is misspelled according to modern convention! As rule of thumb if it does not appear in dictionaries of old words it was not a word at all. Although the Oxford English Dictionary Online requires a subscription it is an invaluable aid to transcribers. Scots had its own peculiarities – most commonly ‘sch’ for sh and ‘quh’ for wh. In addition ‘and’ was the usual Scots termination for verb forms now ending in –ing – e.g. ‘teland’ for tilling (as in land). Words ending ‘ed’ were often replaced by –it, –yt or –at – e.g. ‘clothit’ for clothed. An ‘is’ at the end of a word indicates a plural e.g. ‘debtis’ for debts. Often if preceded by an adjective this too will be in the plural e.g. ‘the saidis debtis’ meaning ‘the said debts’ etc. Punctuation Punctuation was virtually non-existent in the form we know it today, which can make the interpretation of documents tricky too. Again reading out load may well help you make sense of what has been written and help you spot any inadvertent omissions! Conclusion  Clearly it is impossible to cover every aspect of palaeography in one short blog, but I hope the brief overview and hints and tips above have inspired you to have go at tackling some older documents. If you are still feeling unsure of how and where to get started, keep an eye open for opportunities to learn through practical projects run by local archives or history societies. Alternatively, I shall again be running two workshops at Family Tree Live the 17th and 18th April 2020 at Alexandra Palace. The workshops are included in the price of admission to the show but must be reserved in advance. Workshop places and admission tickets can be booked online at the same time you purchase a ticket at https://www.family-tree.co.uk/information/family-tree-live-workshops If you would prefer some ‘one to one’ personal tuition, perhaps using documents that relate to your own personal research project then please do get in touch. Then again, if you would like to me transcribe the documents for you I would be delighted to do so too! Useful Resources for Transcription

Online Dictionaries Dictionary of Scots Language http://www.dsl.ac.uk/ Oxford English Dictionary http://www.oed.com/ (requires a Subscription or is available for free through many public libraries) Latin Dictionary https://www.latinitium.com/latin-dictionaries This brilliant new site also has the benefit of English to Latin Books Hilary Marshall ‘Palaeography for Family and Local Historians’ Philmore, 2010. Bruce Durie ‘Understanding Documents for Genealogy & Local History’, Stroud, 2013 For Scots Grant G Simpson ‘Scottish Handwriting 1150 – 1650’ Edinburgh, 1998. Websites Pit your palaeography skills against the ducking stool with The National Archives http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/ Some further guidance and practice available at https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/medievaldocuments/introduction.aspx An online course in conjunction with Cambridge University https://www.english.cam.ac.uk/ceres/ehoc/

5 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy