IntroductionAs a researcher by far the most frequently asked question I receive concerns marriage records, or indeed the lack of them. Whilst the terms “clandestine “ or “elopement” conjure up images of a hopelessly romantic nature, the term “irregular” infers something seedy and underhand. This is simply not the case, regardless of the derogatory comments entered in the baptismal registers for the children resulting from such unions by mealy mouthed ministers.

Marriage in England – Clandestine & Otherwise. In the years before the Hardwick Marriage Act of 1753, for a marriage to be legal it merely required to be overseen by a minister of the Established Anglican Church. In many cases this was preceded by the calling of banns in Church or the acquisition of a marriage licence. However these methods were discretionary rather than mandatory until the passing of the “Marriage Duty Act of 1695”. This effectively prevented marriages taking place in Church without banns or licence which came at a cost (tax) and heavily penalizing any clergyman who did otherwise.

Marriage in Scotland – Regular & Irregular.

Here for a marriage to be deemed ‘regular’ it merely required the ceremony to be carried out by an ordained minister, and to be preceded by proclamation or Banns. Parental permission was not required, girls as young as 12 and boys of 14 could legally marry without it. This rule remained in force until 1939, when the age of consent was raised to 16 for both sexes. Neither was it a requirement for the couple to marry in a Church. It was not uncommon for the ceremony to be carried out in the Bride’s home, or the parish Manse. Irregular‘Irregular’ marriage in Scotland did not require any of the above to be recognised as a legal entity. Nor did it require residency until the reform bill known as the “Cooling Off Act” was passed in 1856, introduced by Lord Brougham, the Scottish born former Lord Chancellor. Prior to this date to be recognised by law, an ‘irregular’ marriage came in three basic forms:

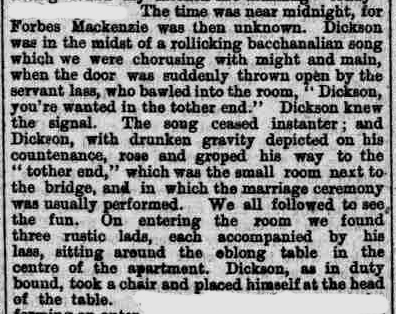

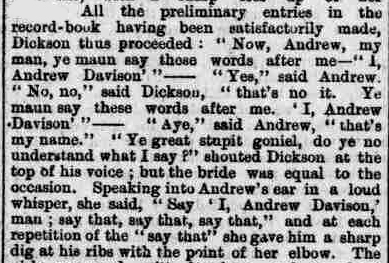

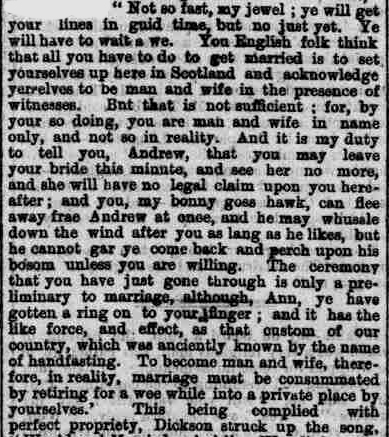

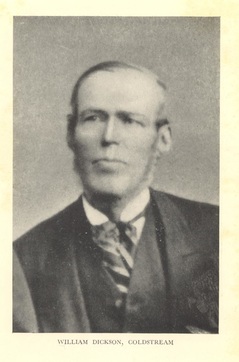

Whilst frowned upon by the Scottish church, it was tolerated for fear that if not recognised by law, the couple involved would be deemed ‘living in sin’. References to ‘irregular’ marriages regularly appear in Scottish Kirk Session Minutes, when the couple would be reprimanded and either be married again or required to pay a fine, or sometimes both. As such I fear the bemoaning by the Church was often attributable to its loss of revenue rather than the absence of the Almighty! Thus from 1754, Scotland provided English sweethearts with the opportunity for elopement. The fame of Gretna Green spread and became synonymous with clandestine marriages. However, Gretna was not alone, and neither was it unique to English couples unable to gain parental consent. Border crossing points along the Eastern side of the country sparked up a brisk trade in such marriages too, Lamberton Toll, Coldstream, Paxton Toll, Mordington to name but a few. This system of marriage also appealed to other social groups and members of dissenting religions, particularly Presbyterians. It was particularly popular with agricultural workers who needed to marry in a hurry, because of the lack of opportunity presented by the remote rural nature of the Border region. The twice yearly ‘Hiring’ fairs, market days and holidays would see a surge in business in towns throughout the Borders. A former jeweller in the town of Berwick states that it was not unusual to sell 12 – 18 rings on such mornings, for use later that day at Lamberton Toll. A fabulous, and highly amusing, if somewhat lengthy article appeared in the ‘Berwickshire News and General Advertiser’ on 12 March 1889. It is the recollection of a former incumbent of Coldstream Toll, then called the Bridge Inn, whose backroom was used for the purpose of irregular marriage (and a further room for consummation thereof) on many occasions, in this case the marriage of Andrew Davison & Ann Scott of Shidlaw Farm, with William Dickson presiding. It has gone midnight and the narrator and Coldstream “priest” Dickson have already enjoyed a profitable evening and are now both evidently somewhat in their cups: Then we come to exchange of vows and Andrew’s declaration: Vows exchanged, the bride, who had been rather vociferous throughout then demands her certificate from Dickson, who gently reminds her that as yet the job is only half done: From it we can glean a host of information about the, ‘who, where, when and why’ and the celebrants calling themselves “priests” who conducted such proceedings. We learn for example that the spring hirings in England were a particularly busy period with up to 10 “cases”, presenting themselves for marriage during the night and hours of darkness on Fair Day at Wooler, alone. Our narrator also confirms that this practice was equally popular amongst the local rural Scottish population residing on the north side of the Tweed.

The last entry in Dickson’s register appears on 25th July 1857. He is known to have officiated at 1,446 weddings. It is believed there may have been many more. “A Riotous Affray at Lamberton Toll” Another marriage documented in the newspapers albeit for the wrong reasons, was the marriage of George Gibson and Ann Metcalf at Lamberton Toll on the night of 5th March 1842. Witness statements to the ‘riot’ that ensued, hold a wealth of useful information for the family researcher:

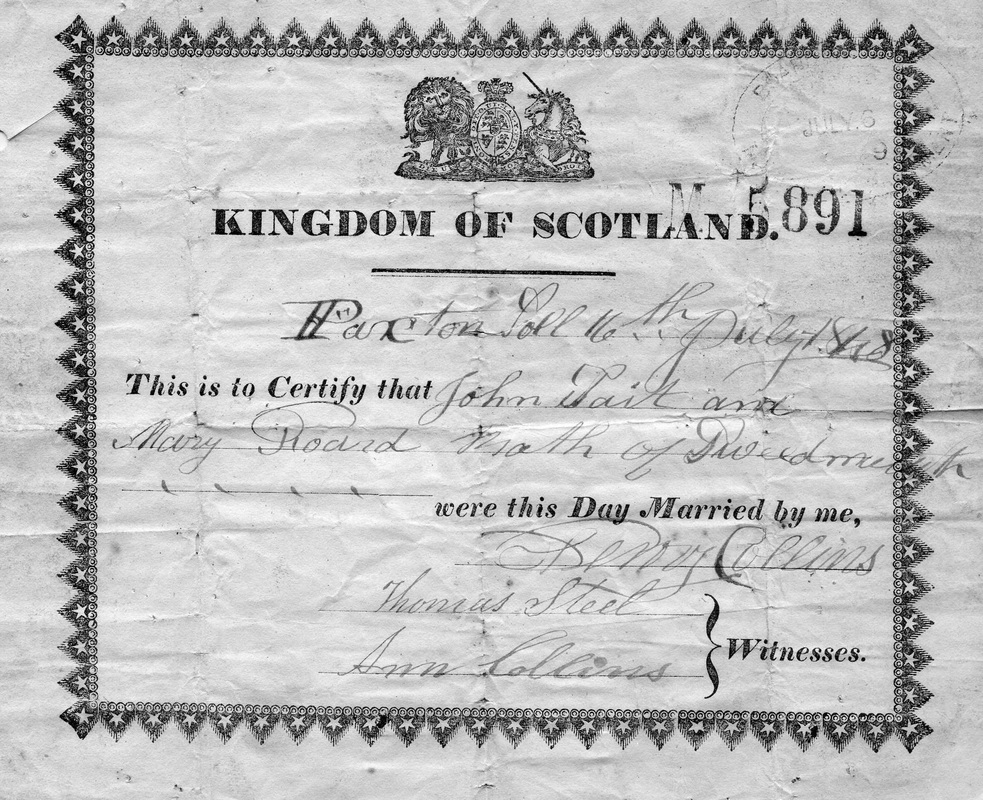

From this evidence it is possible to trace George Gibson and his wife Ann through the census records. In 1851 George is a miner at Greenwich Colliery, Scremerston, he was born in Ancroft, Northumberland in 1817, Ann was born circa 1821 at Tweedmouth, and they have three children. In 1861 they have moved to Broomhill Colliery, Morpeth and have five children. In 1871 they are residing at West Chevington and the census states “formerly a miner, out of health”. A death record for a George Gibson appears in the October Quarter of the same year in Morpeth. He was survived by his wife Ann, at least two of his children, sons Thomas 28, and John 19, both coal miners. There is a potential baptism for Ann in Tweedmouth in 1820 to parents John & Catherine Metcalf. Two of Ann Gibson’s daughters were named Catherine. However, the final twist comes from the 1841 census. George Gibson appears next door to George & Catherine Metcalf and family in Unthank Square, Tweedmouth. Occupations coal miners. Whilst Ann is not present the evidence that this is indeed her family is compelling, especially when backed up by witness statements to their riotous nuptials from other residents of Unthank Square! A Change in the Law and it's Economic Impact The narrator in the newspaper article of 1889 remonstrates on the change of the law regarding the 21 day residency rule introduced in 1856, with the passing of Lord Brougham’s ‘Cooling Off Act’. Cool off it did but the practice of irregular marriage continued, albeit on a much lesser scale until its abolition in 1939. The change in the law obviously hit his pocket hard. He says: “My malison be upon all those who took “airt and pairt” in the making of a law which deprived me and many more of a considerable amount of income and poor folks the pleasure of getting cheaply married without the compulsory interference of a busybody in the shape of a minister or a registrar who cannot tie the marriage knot one whit tighter that I have seen it done in my ain house in the auld fashioned way.” Ironically, tradition has it that Lord Brougham himself was married in Coldstream under the old system circa 1819 at the ‘Newcastle Arms Inn’, but as ever there is no surviving written record! Further Reading & Henry Collins Henry Collins was another renowned border “priest”. His registers from “Marriages at Lamberton Toll 1833 to 1849” have been transcribed by Northumberland & Durham Family History Society and are available for purchase, as are the Registers of George Lamb (1804-1816) and George Sharpe (1849 – 1855). Collins was an uncommon character and a degree of lateral thinking is required when deciphering his entries. His spelling is random to say the least. The surname of the bride on the certificate above is actually ‘Ford’! You can also expect to find place names such Cockburnspath written as Coppersmith, Glororum as Gloweram etc. Berwick Record Office also has the above records, and in addition has transcribed irregular Border marriage entries in local newspapers, 1808-1864 and holds a few surviving certificates including the one above. http://www.experiencewoodhorn.com/berwick-record/

Or you could of course just ask me of course, as I hold these records within my ever growing collection, which also includes Coldstream Bridge Marriages 1793 – 1797. A simple email will suffice! A comprehensive list of where to source other records can be found at: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/guides/birth-death-and-marriage-records/irregular-border-marriage-registers#current whereabouts

51 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy