|

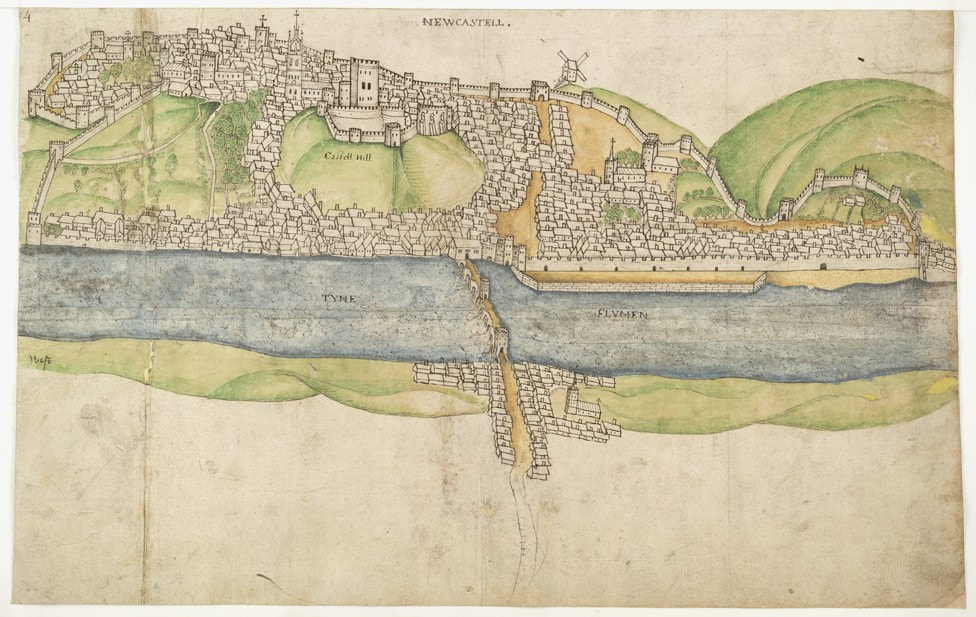

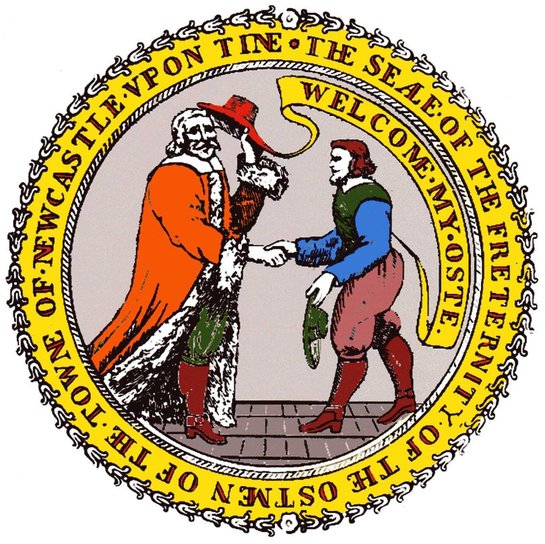

Something a bit different for Borders Ancestry readers this month. As some of you may be aware I am a bit of a Flodden ‘geek’ but far from the military tactics, political backdrop and the auspicious persons that took part in the Battle of 1513, my interest lies more in the logistics of feeding the English army of circa 20,000 men, their followers and the impact on the lives of ordinary local people. As part of local, rather than family history research the latest rabbit hole I have disappeared down concerns corn and corn production in the early sixteenth century in the area of the English Border with Scotland. Historians seem to be particularly fond of saying ‘The northern Marches were obviously incapable of meeting a sudden demand for the feeding of 20,000 men’. Needless to say this ‘incapability’ is often blamed on the Anglo Scottish Wars and the nefarious activities of raiding parties from both sides of the Border. However, studies to date tend to focus on the macro issues of victualling a peripatetic army during either the period of the Anglo Scottish Wars 1297 – 1603 or the Tudor period from the accession of Henry VII in 1485 rather than the micro level at the time of the Battle. Whilst these ‘raids’ undoubtedly had a significant impact on the local communities, were there alternative reasons that would restrict corn production in the Border Region in the early sixteenth century, if indeed it was restricted at all? The type of farming practised, crops grown, topography and climate perhaps? Furthermore, Flodden took place after a period of relative calm in the Border region following the signing of the ‘Treaty of Ayton’ in 1497 and ‘Treaty of Perpetual Peace’ in 1502. It was not until Henry VIII declared his intention to invade France that rumblings of disquiet once again threatened ‘international’ relations along the Border in 1512. Has the ‘historians’ fondness of portraying the North as a barren and inhospitable landscape occupied by lawless barbarous people been somewhat over exaggerated? The type of forays practised in times of ‘war’ were in the manner of retaliatory Chevauches or ‘short sharp shocks’ which were high localised. They generally involved the destruction of crops and stores by fire and the leading away of booty in the form of livestock and other household goods. After isolated incidences of burning (if they did indeed burn standing crops) the land itself would recover quite quickly, indeed, until it was banned in the UK in 1993, the residual corn stubbles were often burned as it ; quickly clears the field and is cheap, kills weeds, kills slugs and other pests and can reduce nitrogen tie-up. The full transcription of 24 folios (pages) and analysis of the contents of Richard Gough’s account for corn shipments from Hull to Newcastle and Berwick in 1513 forms the basis of my dissertation and matters arising from it my hypothesis. To date this document remains the only complete set of accounts identified to date for; vitayles[1] to be p[ro]vyded northewarde as Whete malt beanys & peson[2] taward[es] the vytayling of late Thomas Erle of Surrey Tresorer of englande grete Capteyn And deputie to owre saide Sov[er]ayn lorde & hys hoost in hys warres northwarde A ganyst the king of Scott[es] & hys subjett[es] Other oddments appear elsewhere which include a payment of £81 to the Mayor of Newcastle (John Brandling) for food ‘spoyled stolen and destroyed’ and a note of debts to Allen Harding of Newcastle and Richard Gough again in 1514. This indicates the potential commercial interests of the merchants, guilds and the Corporation of Newcastle, which suggests they may have had far more involvement in the supply of corn to Surrey’s army than previously discussed in published works. In search of evidence of an earlier corn trade between Hull and Newcastle, the city’s Chamberlain’s Accounts between 1508 and 1511 which was been transcribed in full by Dr C M Fraser in 1987, copies of which can be bought quite reasonably from the Newcastle Society of Antiquaries. This has been analysed and the figures for corn imports extracted and entered into a database. These are the earliest known surviving record of Newcastle’s municipal records and deals with both revenue and expenditure. Whilst I have to admit that scouring each page line by line over the entire 240 pages of entries has probably been the most tedious part of the research process, the results have been most enlightening. However, they come with the caveat that as the Chamberlains Accounts record the levies and tolls payable by the captains of all non Newcastle ships they are an indication rather than a measure of trade. Indeed it was the ‘measurage’ and ‘portage’ at 4 old pence per chalder payable at Newcastle recorded in the Gough accounts of 1513 that helped identify the weight of a Newcastle Chalder (for corn at least) as approximately 4 quarters. I don’t intend to bore readers with the statistical details of corn imports, which came mainly from the domestic east coasts ports of, unsurprisingly, East Anglia and Lincolnshire and whether or not they support my theory. Instead it is to the wealth of other information contained in Chamberlains Accounts and their potential value to researchers of the life and times of the people of Newcastle and its hinterland in the early 16th century which is covered here. The shipments that appear in accounts are primarily concerned with the export of coal, grindstones together with the odd ‘dicker’ (packs or bundles of ten) hides. Whenever this occurred the name of an ‘ost’ is recorded in the left margin above the names of the Chamberlains who signed for the receipt of the monies. The ‘ost’ refers to the Hostman – a group of middle men who enjoyed a monopoly on the sale of coal and grindstones and through whom non ‘free men’ of Newcastle were forced to trade: The hostmen, who were often also the Burgesses of Newcastle and the coal owners, exploited a custom often used in other cities of 'foreign bought and foreign sold'. This custom provided that any goods brought into the town by a foreigner (either an Englishman or an alien) who was not a freeman, could be bought only by a freeman, and similarly any goods purchased must be bought from a freeman. Thus, in every case of a purchase or a sale, one of the parties must be a freeman.[3] The records are name rich, and amongst their number many will be familiar such as Brandling, Bell, Carr, Ellison, Robson, Ridell, Sanderson, Southern and Thomson. The Master of the ship and port to which he belonged is also recorded which illustrates the extent and pattern of both domestic and international trade of ships entering Newcastle for coal. Inbound cargoes from the Netherlands included apples, wine, herrings, potash, soap, tar, pitch with tiles from Antwerp and onions from Amsterdam to name but a few. From France came nuts, prunes, salt, glass, iron and the occasional loads of corn but the overwhelming incoming cargo and indeed that which dominates the accounts both foreign and domestic is stones! By far the majority of the ships entered Newcastle either ‘empty’ (carrying goods which attracted no levies and therefore not recorded) in ballast or carrying stones. This potentially highlights the importance of the outbound cargos rather than the import of corn and other goods. Although no purpose is ever stated for the incoming stones the prodigious number of entries under expenses paid to the Paviour (John Dun) and Masons (numerous) must surely be significant. Maintenance of the roads and bridges was clearly a priority. In the latter entries there are also frequent references to the building of a ‘newhous’. These expenditure accounts are also name rich with many more lowly labourers, messengers, and city gate keepers – William Smith the keeper at Sandgate, Ralph Smith for keeping Westgate – are also mentioned by name no matter how small the service they rendered. Women too appear amongst their number, sometimes listed as ‘wife of’ and others such as Dame Hebbron at White Friars, Wilkinson’s wife in the Cloth Market named as keepers of kilns and bakehouse ovens, and Proffett’s wife for ringing the bell in the Big Market. Gutter cleaning, snow clearing, ‘dightyng ramell fro Pylgramstrett pantt’ (clearing rubbish from Pilgrim St pant) the giving of alms, even to inmates of Newgate Prison, and what appears to be the occasional burial all get a mention. The Feast Day of St John the Baptist on 24th June which was celebrated the night before with dancing and copious amounts of wine. In June 1509 the Guild gave a hoghead of wine (63 imperial gallons) to the town (in 1500 estimated to equate to circa 5,000 inhabitants) at a cost of 20 shillings, which does not include the 3 gallons of wine supplied to the major himself at a cost of a further 2 shillings. It appears the dancing ‘affor the mair’ was done by ‘schippmen’ or sailors at a reward of 2 shillings – were these perhaps the colourful keel boat men who ferried the coal from the shore to the ships moored in various streches of the river? There is evidence from the seventeenth century that these ‘Keelers’ were largely comprised of Scots but whether this was the case during the sixteenth century is not known. There is also evidence that St George’s Day was observed when in April 1510 materials and labour was expended on constructing and painting a dragon. As the accounts span the death of one monarch and therefore the coronation of another it was somewhat odd to find no reflection of this within the accounts, other than the movement of the ‘great guns’ and ‘clearing the hill’ on the 28th April 1509, a week after the death of Henry VII. Had the guns been taken to a high point such as the Town Moor and fired to let the townsfolk know they had a new monarch? Another occasion when copious amounts of wine was consumed was recorded on 20th February 1511 to toast the ‘triumph of the prince’. If this was a celebration of the birth of Henry VIII’s first son Henry, Duke of Cornwall, born on New Year’s day, it was late - if it was to mark his death it was two days early!

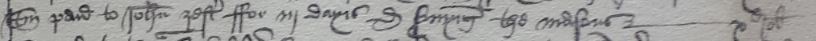

What is also interesting to note, is the language in which the accounts are written. It is a definite hybrid of Scots and English, typified by the use of the ‘qw’ in place of a ‘wh’ in ‘wheat’ and ‘white’, the Anglo Saxon yogh ƺ in place of a consonant ‘y’ (the letter ‘y’ was also used as an alternative for the vowel ‘i’ at this time) so the surname ‘Young’ appears as ‘ƺong’. The endings of plural nouns in ‘is’ as in ‘collis’ and ‘dayis’, whereas the English documents favour the single ‘s’ ‘es’ or the equivalent contraction mark, and past tense verbs ending in ‘it’ instead of ‘ed’ e.g. departit instead of ‘departed’ reflect the influence of Latin which is typical of Scot’s documents of this period. In contrast there is no use of ‘and’, typically a Scots ending of the English form of the present particle ending ‘ing’.  Extract from the original document, courtesy of Tyne and Wear Archives. 'It[e]m paid to John yest[er] (note the yogh in place of the consonant 'y') ffor iij dayis (note the 'is' ending) d[imi] s[er]vying (note the yng ending where the y is used in place of the vowel 'i') the masons 10d ob (10 old pence halfpenny)' The Chamberlains Accounts of such an early period might not be at the top of everyone’s reading list, but for the history and customs of the town at the beginning of the sixteenth century it makes rich pickings and is well worth a read. As for the other evidence for corn production in Northumberland and North Durham at this time, other records such as manorial records, corn tithe information, rent payments, correspondence (usually complaints) and inventories attached to wills need to be consulted. However, these can be rather dry when compared to the accounts of the Newcastle Chamberlains. Examples of some early wills and inventories have been transcribed by the Surtees Society and are available online but be warned the early examples are written in Latin. In the words from the film ‘Meet Joe Black’ there is nothing ‘as certain as death and taxes’ but these are records where the information I seek can be found. [1] Victuals meaning food or provisions of any kind. ‘Occasionally applied to food for animals, but more commonly restricted to that of persons’. Oxford English Dictionary http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/223242?rskey=osF6WP&result=1#eid [2] ‘Peson’ is the archaic word for peas. [3] Peter D Wright, Life on the Tyne: Water Trades on the Lower River Tyne in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, a Reappraisal, Abingdon, 2016, p4. Three centuries of English Crop Yields 1211-1491 Crop Yields Database

2 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy