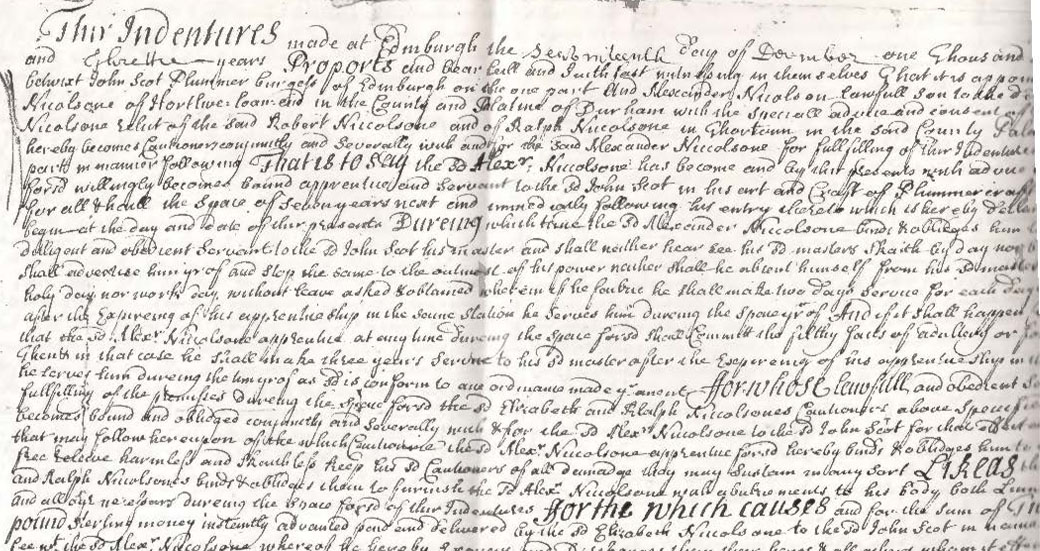

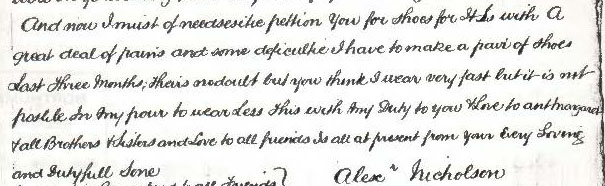

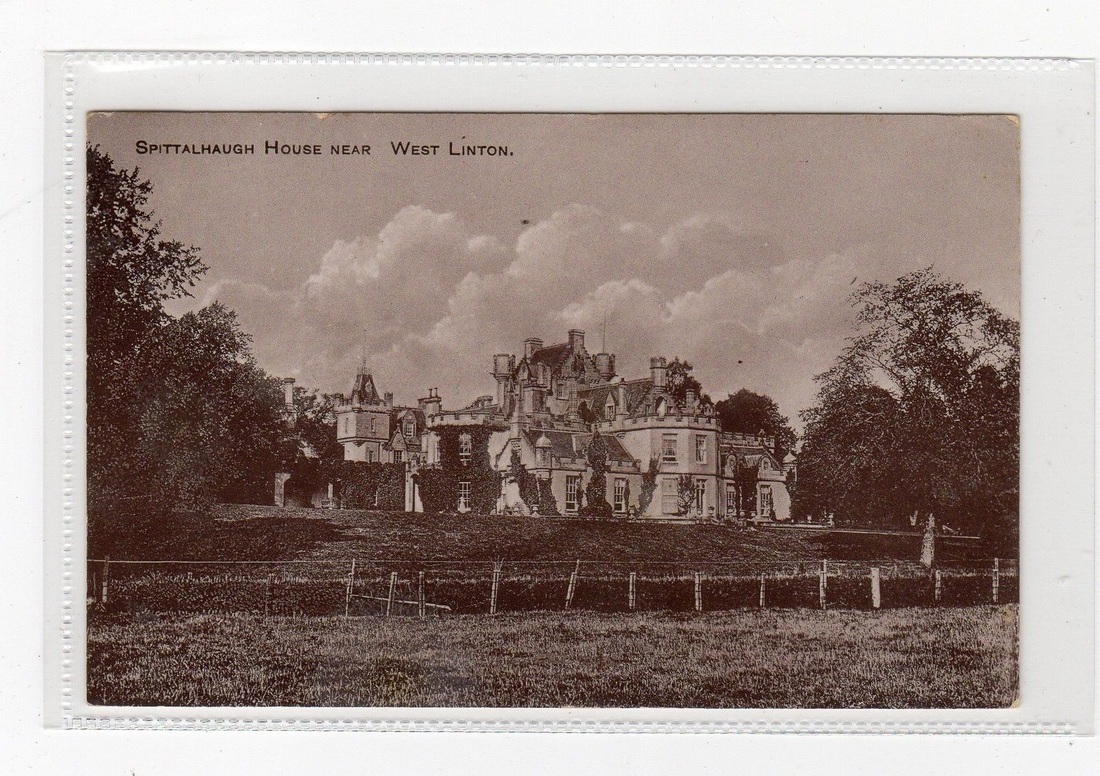

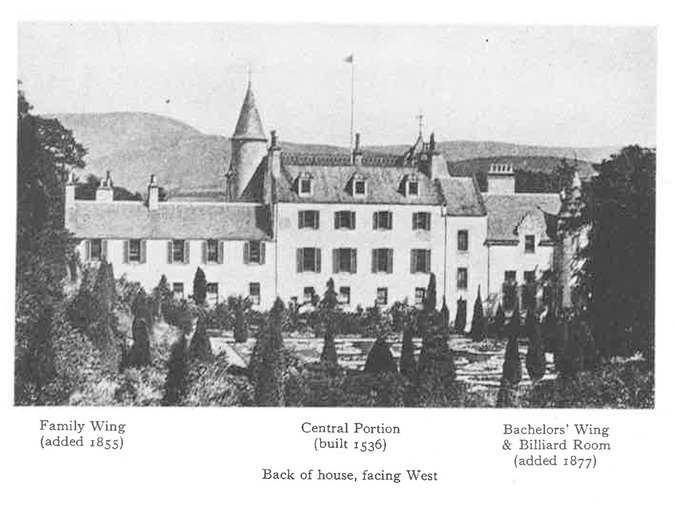

IntroductionHaving now begun my third module of study ‘Public History’ towards an MLitt with Dundee University, I decided to take a break from wading through the monotony of text books and try something ‘visual’ instead. To this end I thought I would investigate the ‘Outlander’ phenomena, which although appearing in print back in the 1990’s, it recent appearance as a televised series overseas is proving a valuable ‘cash crop’ for the Scottish tourism industry. As a member of Amazon Prime it is possible to watch the series that has been televised so far, so that is exactly what I did - all 23 of them, which at around an hour long each, was some task. Top-tip if you fast forward through the ‘steamier’ bits it speeds the process up no end! If you haven’t watched the series or read the books I shan’t ruin the story for you, but suffice to say it centres around a woman from 1945 travelling back in time to 1743 and into the life of one James Fraser in the run up to the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. What I was looking for through this exercise was how these events from the past were being presented to the public, and for historical anomalies along the way. Again I shan’t spoil the story, but should point out that the producers had a serious ‘Oops’ moment in the first episode of series 2. The caption reads ‘Le Havre 1745’ when it should in fact read 1744, which becomes glaringly apparent as the series progresses!  'The Black Stool, or Stool of Repentance, by David Allan (1744-96). A young bachelor is accused of fornication. The luckless lass, seen with her angry mother in the lower foreground, bewails her fate, while his parents on the left hang their heads in shame'. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_religion_in_the_eighteenth_century#/media/File:David_Allan_The_Black_Stool.jpg This process got me thinking about how snippets of information from our own family history research can be woven into historical context, and developed into a story either factual or fictional. After a bit of rummaging and discarding a missing skeleton, countless drownings in the River Tweed and a hen that proved fatal for a young man on his bicycle, I remembered a letter written in 1771. This letter was written in Edinburgh by Jacobina Nicholson to her brother Alexander. It concerns pairs of monogrammed stockings, one pair of which contained a note hidden in the toe; ‘Look at the toe of one of the dark stockings and you’ll find something, be sure to burn this.’ Jacobina Nicholson was the daughter of Alexander Nicholson of Edinburgh and Loanend, but here I am approaching the end of the story, so better go back to the beginning. It is perhaps not the bodice-ripping ‘tartan fest’ that is Outlander but it is an interesting real life parallel none the less. Ironically, it was directly influenced by the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 that deposed the Catholic King James Stewart II of England, and which sparked the Jacobite uprisings. In 1688 following the Glorious Revolution, Presbyterianism had returned to Scotland, and one Rev’d Alexander Nicholson, fled his position as Episcopal minister of Bunckle and Preston to Holy Island taking the parish registers with him. (It is often stated he was a cousin of Thomson the poet, but with a lack of evidence this seems somewhat dubious). The same year his daughter Elizabeth was born, who through the passage of time and marriage to Robert Nicholson of Loanend would become Jacobina’s grandmother. Together Robert and Elizabeth Nicholson had seven children, one of whom James ‘a hopeful youth and unfortunately drowned aged 20 in the Tweed’, but it is to their second son Alexander born in Norham on 1st February 1715 that the story now turns. Alexander’s father Robert died in 1721 aged just 33 and Loanend passed to his elder brother George. In December 1730 Alexander was apprenticed to John Scott, plumber in Edinburgh, who I feel sure from evidence contained in much later letters, is connected to the Scotts, Wilsons and Chalmers of last month’s post, but owing to time constraints, (this) will have to wait for another day. Indeed it may be this earlier familial connection which secured Alexander’s apprenticeship. This was secured by an Indenture dated 17th December 1730 and the payment of a bond amounting to £20 paid by his mother and his Uncle Ralph Nicholson of Thornton. As well as detailing the seven years duration the indenture contains some interesting terms and conditions. Most notably Alexander was forbidden to be ‘accessory to any Mobbs, Tumults, Combinations or insurrection whatsoever within this City’. There are also some interesting stipulations regarding wearing apparel. His mother and Uncle ‘To furnish (Alexander) with acoutrements to his body, both linnen woolen and other necessaries’. This would account for his frequent requests for shirts and shoes sent to his mother. Alexander seems to be particularly hard on shoes, struggling to make them last 3 months (letter from Feb 1736/37) His preference of shirt fabric is also far removed from our highland friends preferring blue and white over plain white ‘for the white shirts are more wore in the washing than they are of the wearing’. Alexander was a perfectly ordinary Englishman learning a trade and living in Edinburgh and could easily have blended into the background of the tv series as an ‘extra’. He opens this letter of the 16th February with an account of an illness which had him ‘8 or 10 days not only confined to the house but also confined to Bed with a diseas they call the could or a Lingering feaver … such a dangerous a diseas that is proving so very mortal in this City’. Alan Stewart notes in his book Tracing Your Edinburgh Ancestors: A Guide for Family and Local historians ‘From 1735 until February 1736 there was an occurrence of relapsing fever, a disease that is spread by lice and ticks, and caught by people living in insanitary conditions’. Three days later on 19th, Alexander wrote to his uncle Ralph expressing concern over the contents of a letter written by his mother to his master. He has yet to hand it over to Mr Scott and fears if he does so it will put him in a ‘prodigious huff’. He is anxious Mr Scott may ‘be provoked now, when business is scarce to turn me off which is a very hard case to be so long a slaive as I have been and to prove all to non effect’. This makes me wonder if this is referring to his period of absence from work conflicting with the terms of the indenture? Whatever the reason Alexander is obviously being worked hard, and worried that he will lose his position in the final year of his apprenticeship. That he remained in Mr Scotts employ is evident from a letter to his mother in September 1738 having spent a pleasant month with him in the country. Once again he is asking for shoes! Now in want of a wife, like Claire the outspoken time travelling heroine of ‘Outlander’, Alexander takes the daughter of a Peebleshire baronet for a wife. (At this point it should be noted that although Alexander is a plumber by trade he came from an armigerous family himself. His grandfather George Nicholson of Loanend was granted a coat of arms by Cromwell for ‘generous hospitality’ received by his troops allegedly en route to the battle of Dunbar.) In circa 1745/46 around the time of 1745 Jacobite Rising Alexander married Margaret Murray, the daughter of Sir William Murray of Spittalhaugh and 5th Baronet of Blackbarony. The marriage date has been entered in the Edinburgh register under the 19th January 1746. However, on closer examination although written in the same hand I feel this has been added as an afterthought for reasons I shall come to presently. The Murray family have a long history at Blackbarony, and by strategic marriages made throughout the course of the sixteenth century forged strong family alliances between their various branches the Scotts of Branxholme and Buccluech and the Kers of Ferniehirst. A strong and powerful family indeed. ‘Throughout the 17th century the power and influence of the Murrays of Blackbarony increased until Sir Alexander was the proprietor of practically the whole parish including the White Barony to the east of Eddleston water. The Scot’s baronial style house was evidently deemed to be an inadequate expression of his status so, between the years 1700 and 1715, the laird built the French (Jacobean) façade which we recognise today. This spectacular edifice, reminiscent of a French chateau, was said to present a more elegant style (sic) of architecture than any seen in the county making the old house appear “regular and beautiful”. The revamped house, Darnhall, must have caused quite a stir among the locals’. The first of Sir William’s direct ancestors linked with Blackbarony was John Murray, born in 1469 and who died fighting for James IV at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He was created ‘Laird of Blackbarony’ in 1506 and was the great grandfather of the 1st Baronet Sir Archibald Murray; Sir Archibald Murray, of Blackbarony, co. Peebles, 2nd but 1st surviving son and heir of the seven sons of Sir John Murray of the same, M.P. [S] for Peebles-shire, 1608 and 1609, by his 1st wife Margaret, daughter of Sir Alexander Hamilton of Innerwick, had charter of lands, v.p., 13 August 1607 and 21 December 1613, being then 'of Darnhall'; was Knighted by James I when young; was M.P. [S] for Peeble-shire, 1617 and 1625, and was created a Baronet [S] 15 May, sealed 25 August 1628, but not recorded in the Great Seal Register, as 'of Blackbarony', with rem. to heirs male whatsoever, and with a grant of, presumably, 16,000 acres in Nova Scotia, of which he had seizin in October 1628. He married before 1617, Margaret Maule. He died before 1 March 1634."

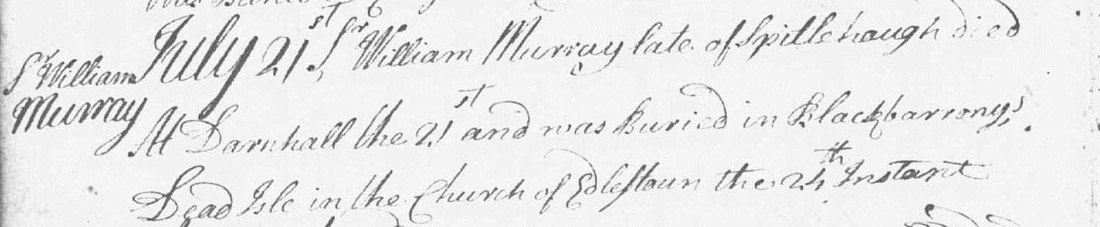

Alas, William did not enjoy his baronetcy for long as he died on the 21st July 1744 and was buried in the Blackbarony ‘Dead Aisle’ of Eddlestone Church on the 24th. Here my sincere thanks must go to Fergus Smith of Old Scottish http://www.oldscottish.com/ who has succeeded whether other renowned researchers of the peerage have failed, by finding William’s death and burial record. William was succeeded by his eldest son Richard. Barony Castle otherwise known as Darnhall is now a hotel and paradoxically also has links to the ‘Outlander’ series through events during WW2 when it was occupied by Polish Troops. The grounds of the hotel feature a relief map of Scotland which was: ‘the brainchild of Krakow-born Jan Tomasik (pron. Tomaashik), a sergeant in the 1st (Polish) Armoured Division, who had been stationed in Galashiels and had married a Scottish nurse in 1942 after being treated in the town’s Peel Hospital for the effects of a wound. He became a successful hotelier in Edinburgh after the war and added Black Barony to his properties in 1968’. Time travelling Claire was also a WW2 nurse! I had hoped to visit the hotel this weekend to take some first-hand photos, but alas it is fully booked. It will keep for another day, but in the meantime the hotel website contains a wealth of information. http://www.baronycastle.com/ In 1709 William married Jean Allan in Edinburgh and together they had 8 children. Their daughter Margaret was born on 6th November 1712, making her age 32/33 when she married Alexander Nicholson. Together the couple had at least five children, 4 of which are known and proven to have survived into adulthood, not three as reported elsewhere. Their eldest Robert, was born on the 21st of November 1746 (not 1741 as widely stated) and was baptised later the same day. Present as witnesses are Margaret’s two brothers Richard, now 6th Baronet and Archibald. It is this record which is undoubtedly correct that makes me question the marriage in 1746. Why?, because until 1752 the calendar year ran from Lady Day (25 March) to Lady Day. If this marriage entry is correct then it would mean that Alexander and Margaret married 2 months after Robert was born. i.e. January 1746 came after November 1746, in today's terms this would be recognised as 1747. The baptism record clearly states Margaret is Alexander’s spouse, and as the Church was pretty fierce regarding illegitimacy at this time, I can only think it is the marriage record that has been incorrectly entered in the records. Subsequent children that survived until adulthood were Jane, and the correspondents from 1771 concerning the mysterious contents of the monogrammed stocking, Jacobina in Edinburgh and Alexander, now residing with his Uncle George at Loanend to further his education. At the time of his birth and baptism, (the same day) on the 5th February 1758 the family are living in the Tollbooth Kirk parish in the 'Old Town' of Edinburgh. The lives of these siblings would prove most eventful indeed. Fortunes gained and fortunes lost, heroism and lunacy, love and loss, rumours of south sea cannibals and the displacement of orphans, but for those stories dear reader, you will need to tune in next time. The letters and papers referred to in this article were in the possession of the Smith family and were deposited with the Northumberland Record Office under the reference NRO.1955/A. They are now held within the Archives at Berwick. Other information has been gleaned from the research originally under-taken by George Aynsley-Smith when assisting John Crawford Hodgson in the compilation of ancestral trees of Northumbrian families. This work was continued, transcribed and updated by his son Philip, whose extensive family archive is currently in my care. Needless to say all the dates appearing above have been verified and in some cases corrected by myself. However reliable your source it is always worth undertaking your own research! LinksBarony Castle Hotel http://www.baronycastle.com/hotel/the-history-of-barony-castle/ Red Book of Scotland http://www.redbookofscotland.net/database/ Scotlands People http://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/ Berwick Records Office http://www.experiencewoodhorn.com/berwick-record/ The Rise of Edinburgh http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/scotland_edinburgh_01.shtml A History of the Murrays of Blackbarony, supplied by the Barony Hotel

The Scottish Middle March, 1573-1625: Power, Kinship, Allegiance By Anna Groundwater Tracing Your Edinburgh Ancestors: A Guide for Family and Local historians By Alan Stewart

4 Comments

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||||

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy