|

This month’s blog is in response to an increasing number of requests, queries and comments I receive concerning surnames. The most common queries involve spelling, or why ancestors can’t be found, but with more and more men testing their Y-DNA either to solve a mystery of an unknown male ancestor or to uncover more about the origins of their patrilineal or direct male line, test results are throwing up more questions than ever; Why do I not know any of the matches with my surname, why are there different surnames in my matches, why is my surname not amongst my matches. Surname SpellingsQuestions or comments regarding the spelling of surnames continue to crop up regardless of countless blogs and articles on the topic. I would be rich indeed if I had a penny for every time I heard, they can’t be related as their name is spelled differently! Therefore, although one rule by no means fits all and there are always exceptions, I shall try to set out a few pointers. Top Tips regarding Surnames in Documentary Evidence

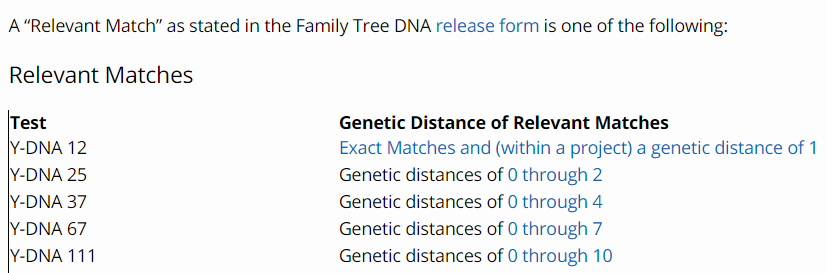

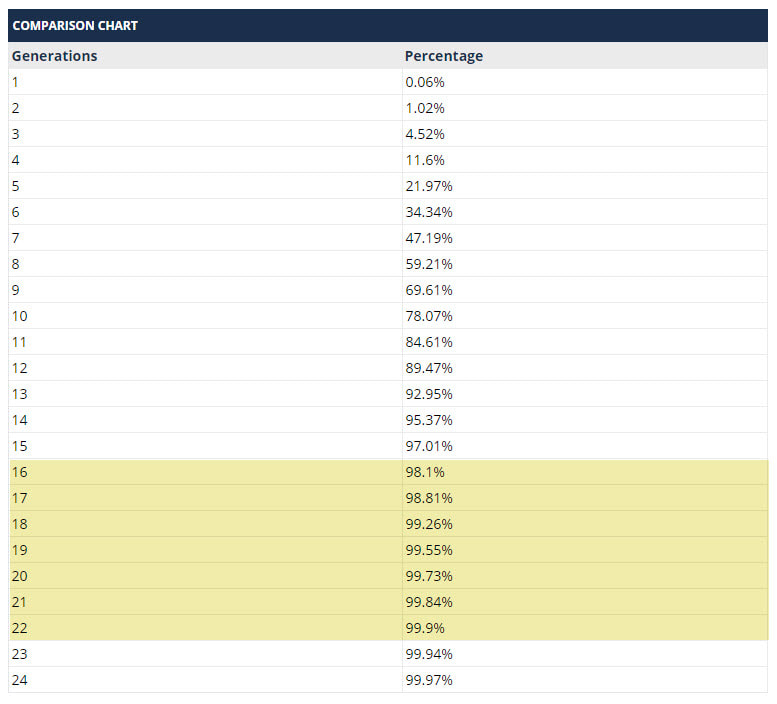

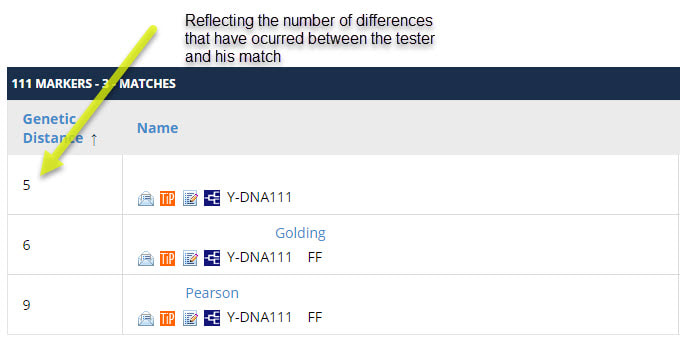

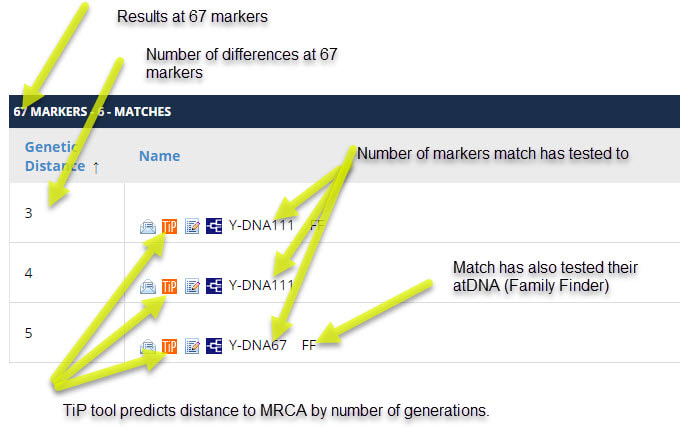

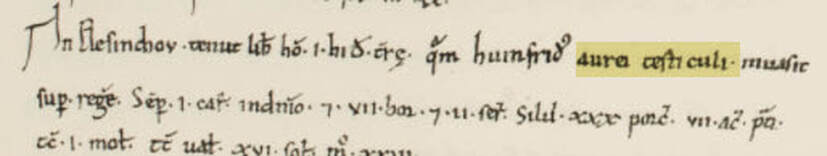

Y-DNA - The Test for SurnamesWhilst the numbers of men testing their Y-DNA remains relatively small, the test is increasing in popularity and the numbers of testers is increasing rapidly. The relative paucity of testers accounts for one of the most common reasons for a lack of matches sharing a surname. The environment and way in which results are presented is also rather different to at-DNA and gives rise to other specific questions relating to surnames, or perhaps lack of them! Y-DNA is the definitive test for ‘surnames’ as it is limited to male testers only as it passes solely from father to son and is neither inherited nor carried by women. It works by testing either STRs (Short Tandem Repeats) or SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) on the Y chromosome. The introductory test for investigating a surname using Y-DNA is the STR test which tests numbers of STR markers 12, 37, 67 or 111. The higher the number of markers tested the more accurate the prediction becomes regarding in which generation the match with another tester has occurred. The Family Tree DNA programme has parameters for returning potential matches based on the number of differences (Genetic Distance) that occur on markers between two testers, subject to the level of markers tested. In such a way matches which differ on more than one marker in 12 tested, two in 25, four in 37 tested etc., will not be shown as matches at those levels. However, the more markers tested the greater the tolerance of differences. By the time 111 markers are tested, matches with up to 10 differences (a genetic distance of 10) will be returned. However, if 5 of these genetic differences occurred on the first 37 markers tested, that particular match will not show in the returns of the tester at that level of testing. Whilst Y-DNA can predict the closeness of a relationship, it is unable to pinpoint the exact individual in the same way that autosomal DNA testing can. The FTDNA programme uses genetic distance (GD) or the differences, and on which markers they have occurred (some markers mutate far quicker than others) to estimate the number of generations that separate the tester and a match from their most recent common ancestor (MRCA). This is returned using the ‘Time Predictor’ or the ‘TiP’ tool which gives the time frame in generations. A generation usually equates to between 20 and 30 years, so by saying a generation equates to approximately 25 years, and, multiplying this by the number of generations predicted by the FTDNA TiP tool, will give an approximate timeframe to MRCA in years. See example from Pearcy DNA Project below: Pearcy (and variant spellings) DNA Project As reported back in August, David Pearcy tested his Y-DNA in order to delve into his deeper paternal Ancestry. He had one very interesting match with the variant surname of Piercy, whose family were known to have come from a similar geographical area in Northumberland. Initially the match had only tested to 12 markers, but crucially there were no differences at this level. The match then extended the number of markers tested to 111. This returned a genetic distance (GD) of 5. This equates to 5 differences, 1 of which occurred between 12 and 25, another between 25 and 37, a further 2 appeared between 37 and 67 and the final difference occurred between 67 and 111 markers. Using the TiP tool and extending the results displayed to every generation rather than grouping them to four years enables a greater degree of ‘estimation’ as to how many generations have passed since the MRCA lived. Using a percentage of between 98 – 99.9% (but may be more, or may be less accurate) places their most recent common ancestor somewhere between 16 and 22 generations, or very approximately, to have lived 400 & 550 years ago. For me personally, this is quite exciting as it suggests the Pearcy family had an established surname and were living in a close geographic area around Wooler & Ford in Northumberland around the time of the Battle of Flodden in 1513. To draw any more meaningful conclusions however, we need a far bigger Y-DNA sample from male Pearcy/Piercy/Percy & other variant spellings from around the globe. David and I have created a Pearcy DNA project through Family Tree DNA so if you are a Pearcy, or know a Pearcy then please either get in touch or point them in our direction. It is open to all, not just Y-DNA testers, and is completely free to join. https://www.familytreedna.com/groups/pearcy-piercy-dna-project/about (Please note, you will also need to sign-up to Family Tree DNA to join the project if you have not already done so. You do NOT need to purchase a DNA test from FTDNA to join. Registration is completely free of charge at www.familytreedna.com/autosomal-transfer & you do not need to transfer your atDNA if you do not wish to.) Top Tip – The Genetic Distance in Y-DNA Test ResultsThe Genetic Distance figure given by FTDNA reflects the number of DIFFERENCES that have occurred between two testers, NOT the number of generations. To find the estimated time lapse to the most recent common ancestor shared with a match, USE the TiP TOOL. This gives the estimated time lapse in generations. To approximate this in years, multiply by 25. Common Question - Matches of the same surname as myself match me at 12 markers but not 111The most common reason for this is that the genetic distance becomes too great to be relevant and therefore the match at 12 markers is dropped from the match list at higher levels of testing. Another very common reason and one which is easily overlooked is that the match hasn’t actually tested to the same number of markers as yourself. Top Tip – Check the level the match has tested to.Look at matches with the same surname as yourself and check the level that match has tested to. This information appears after the match’s name. If they have tested to a much lower level than yourself this may be one reason why they do not appear at a higher level. This can be remedied by the match raising the number of markers they have tested. In most cases there is no need to retest and the sample supplied for initial testing can be used. Y-DNA Matches with Different SurnamesAny form of DNA testing carries the risk of unearthing unwelcome family secrets but there are many other reasons why any DNA test may not yield the results expected. Second families, adoption and illegitimacy are just a few. In Scottish clan projects, DNA that fails to match with the surname of the chief also results in unnecessary disappointment for some. Whilst kinship was at the core of the clan system, many clan followers or dependents adopted the name of the ruling family even where there was no blood tie. Daughtering Out & Inheritance Another reason surnames may not reflect those expected can be due to a change of name. Historically this sometimes occurred amongst landed families when it became extinct in the male line, in other words ran out of sons or other immediate male relatives of the same surname. Those inheriting the land or heritable estate may have descended down the female line and changed their name on inheritance. A change of surname to reflect maternal line inheritance is a topic I have touched on before, when Thomas Wood assumed the surname of his uncle Shafto Craster on inheriting the estate in 1837. (The Christian name Shafto itself being derived from a surname.) There are also instances where younger sons in landed families have inherited from mothers or grandmothers and have relinquished their patrilineal surname in favour of the female line from which they have inherited. A prime example of this is John Ogle, (younger son of Robert Ogle d.1410) who on inheriting the castle and manor of Bothal brought to the Ogle family by his grandmother Helen Bertram adopted the surname Bertram himself. Helen was herself a sole heiress so John in adopting her patrilineal surname for himself resurrected a line which had itself become dormant in the male line. The most common reason a Y-DNA match does not share a surname, however, is that it predates the introduction of surnames themselves. Surname Origins As research progresses back in time it inevitably reaches a point where surnames cease to exist or have not followed the hereditary pattern of today. Hereditary surnames, or where the same surname passes unchanged down through subsequent generations in the male line, came into use following the Norman invasion of 1066. Before this time, and indeed in some places for some time afterwards, ‘surnames’, second names ‘cognomen’ or ‘bynames’ followed the Anglo-Saxon tradition which was more akin to an ‘identifier’ within a community and changed with every passing generation. They were often drawn from places names, topographical features, occupations, patronymics (son of ‘x’), less commonly matronymics (son of ‘x’ female), nicknames and personal idiosyncrasies. As the first ‘national’ survey undertaken in post-Norman Britain, the names recorded in the Domesday Book are therefore indicative of the early surnames in use at that time. An interesting study into Anglo-Saxon bynames recorded in the Domesday Book by medieval historian Thijs Porck, can be found at Anglo-Saxon bynames: Old English nicknames from the Domesday Book. The contents of the Domesday Book can be found online at the ‘Open Domesday’ with more information about at ‘The Hull Domesday Project’. The Domesday survey was neither representative of the population (as it only listed those with landholdings), nor did it encompass the whole of England. As can be seen from the interactive map on the Open Domesday website, Northumberland and Durham were notable exceptions. The earliest ‘Domesday’ equivalent for the region is the ‘Boldon Buke’ a survey undertaken approaching 100 years later in 1183 on behalf of the Bishop of Durham, Hugh Pudsey. Surnames’ of any recognisable kind are absent, with those few individuals who have been named either identified as a ‘son of’ (filius) ‘Richard son of Ulkil’, ‘de’ meaning of a place ‘Adam de Thornton’ & ‘Wynday de Grindon’ or by a nickname or byname, ‘Elfald Langstirap’. Although the practice of hereditary surnames had been adopted and was in common usage in England by the mid fourteenth century, the north and in particularly the areas of the former Marches with Scotland were slower to follow suite. Dr Jackson Armstrong of Aberdeen University has made an in-depth study into matters of Lordship, Kinship and Surnames along the English border during the fifteenth century in his book ‘England’s Northern Frontier, Conflict and Local Society in the Fifteenth-Century Scottish Marches’. His findings and examples supporting the notion and depth of ties on kinship make fascinating reading and illustrate the significance of collateral paternal as well as maternal line inheritance. (I appreciate the book is not cheap, but for those of you serious about your ‘Borders Ancestry’ this brand-new book comes highly recommended. Part II will be of particular interest to those researching the riding ‘Surnames’ associated with the Border Reivers.) In his new study Dr Armstrong has used 15th century Gaol Delivery books as sources and evidence of use of hereditary surnames. He found that ‘The later Middle Ages were a transitional period in which older bynames co-existed with newer hereditary surnames as a type of cognoma. Consequently, it is not always possible to distinguish one from the other.’[1] As outlined earlier, by-names were drawn from ‘occupations, topographical features, toponyms the body and personal characteristics, animal names and interpersonal relationships denoting kinship (and so taking the suffix -cousin, -son or -daughter) among numerous other potential sources and combinations. Employment was one such source …’[2] Throughout the book Armstrong uses clear and interesting examples to illustrate his findings:

And uses of patronymic naming patterns used simultaneously alongside by-name surnames

And of double patronymic

Although Armstrong notes that these types of combinations are more uncommon in east of the region. He further notes examples of compound names

‘as reasonable to conjecture, described a family relationship by adding a patronym to a hereditary surname in order to assist with identification’.[3] By todays way of thinking the use of middle names may suggest the maternal line surname, but clearly in this 15th century context this is not the case. Extreme care must therefore be taken before drawing conclusions on early lines of decent, particularly where patronymic naming patterns are used.

1 Comment

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy