|

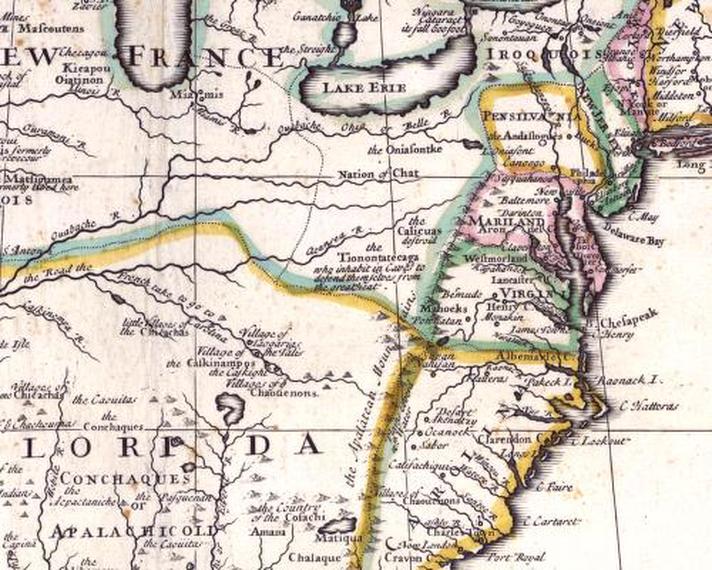

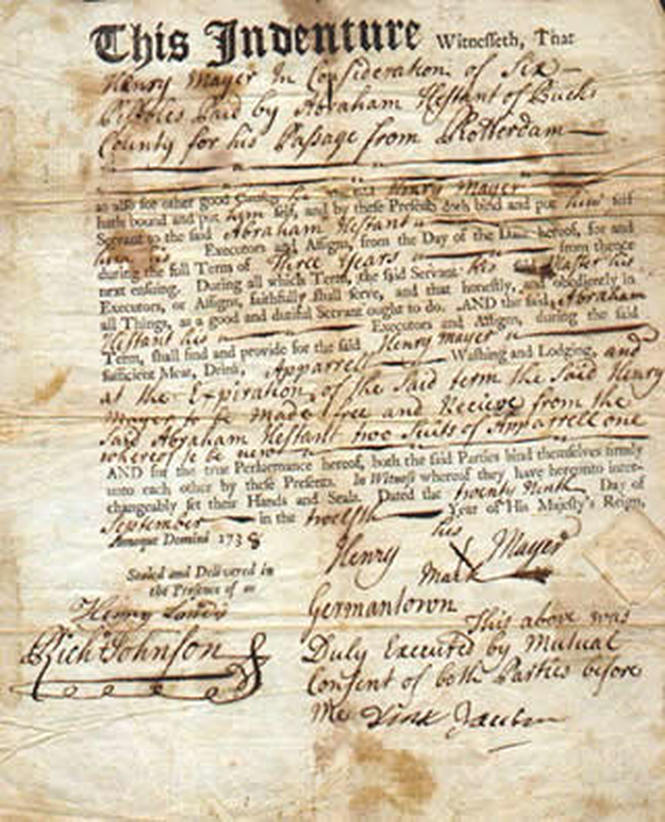

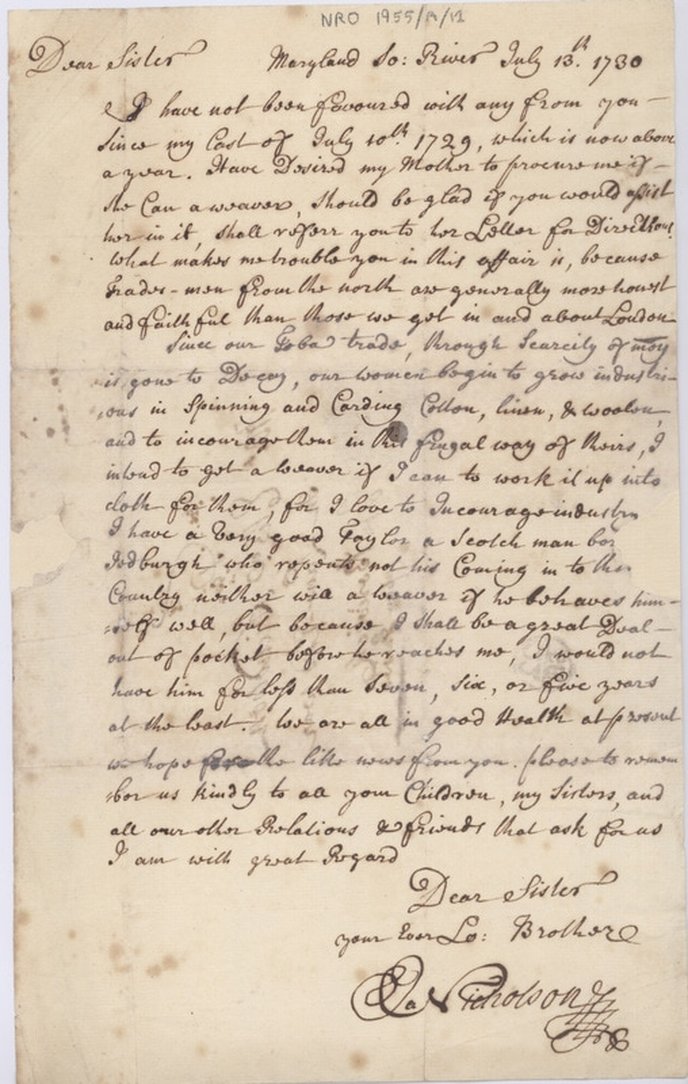

You know the saying about waiting for a bus and then three come along at once? Well the same it seems can be said of requests for research. There seems to be an epidemic of 17th century ‘plantationitis’ doing the rounds! These include the associated rumours of transportation due to criminal convictions and religious persecution, with the ‘victim’ subsequently coming good in the Americas. These cases are topped off with accounts of escaped and freed slaves who went on to found their own dynasties bearing the surname of their previous ‘owners’. That slavery is synonymous with plantations and the whole concept of a fellow human being reduced to a mere possession or commodity to be traded is totally abhorrent, but there is more to the history of the early plantations than meets the eye. Some legacies left have had far reaching impact and longevity spanning centuries as examined in this month’s featured article from Fergus Soucek-Smith of ‘Old Scottish Genealogy and Family History’ who takes a look at a couple of specific ‘Deeds of Mortification’. Before that below is a very brief a look at some of the records that may be helpful when researching early plantation ancestors from Britain. Companies such as The Virginia Company founded in 1606 by royal charter of King James I & VI, (except for viewers in Scotland!), with the purpose of establishing colonial settlements in North America to produce and export tobacco, required a huge labour force. This was often supplied via voluntary ‘indenture’, a means by which poor folks would have their passage to America paid and be provided for in exchange for a fixed period of labour for the plantation owner – typically 4-7 years. At the end of the term they were often given a few acres of land, a cow, some corn etc., to make good their start in the New World. The earliest record in the family archives is of a Ralph Nicholson aboard the Merchant Bonaventure, captained by Mr James Ricroft, bound from London to Virginia in 1635. Several members of the Nicholson family followed, including William Nicholson, who died in Maryland in 1719, and James Nicholson, a nephew who emigrated in 1716 aboard the ‘Jonathon’. In a letter to his sister Margaret, from South River, Maryland, James asks her to assist his mother in finding him a weaver.  Image courtesy of Berwick Record Office, Nicholson Correspondence NRO/1955/A/12 Image courtesy of Berwick Record Office, Nicholson Correspondence NRO/1955/A/12 The letter implies James is to pay the cost in return for between five and seven years of service. The reference to his tailor ‘who regrets not his coming’ is also of interest. Although sadly he is not named, his place of birth being Jedburgh indicates a preference for workers from the Scottish Borders. This sentiment is borne out in his line ‘as men from the North are generally more honest and faithful than those we get from in and about London’. The numbers swelled as English gaols were emptied of ‘idle vagrants’ and pardons were issued on condition of transportation. On Friday, Anthony Wornum, whose family history is also inextricably linked with the Nicholsons, contacted me regarding: ... a catalyst [to revisit the family history, received] a couple of days ago from the branch of the family that settled in the USA. There are many Wornums in the USA descended from a freed slave called Ben Wornum who took his owner's surname (as so many did) when freed. However, this message was from Jane Wornom Swallow, a member of the Wornom family looking for their link to the elusive "John Wornum" who allegedly arrived in Virginia USA in the 1600s having been transported to the colonies for some offence or other. Having the ‘Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage 1614 – 1775’ by Peter Wilson Coldham to hand, I had a brief look to see if he was listed. Despite looking at a few variant spellings I could find nothing. Given a sharp prod by Anthony to try again – Warnum struck gold: Warnum, John. R [reprieved for transportation] for Barbados April TB [transportation bond] Oct 1669 M [Middlesex] Middlesex cases were heard at the Old Bailey, but alas just a little before their fantastic online archive begins in 1674. So, we are still in the dark as to what offence he was convicted of, and just how he fits into the family tree, but this snippet is at least a start. As for religious persecution, which was another reason mooted for an ancestor’s removal to foreign parts (being a Quaker), whilst not finding the gentleman in question, research did find several instances of this being the case. This particular reference from the section ‘Transported Quakers, 1664 to 1666’ at Genealogy Quest dated 7 December 1664 made me smile: Whereas Nicholas Lucas, Henry Feste, Henry Marshall, Francis Pryor, John Blendall, Jeremiah Hearne, and Samuel Treherne, Persons Convicted at the last Assises held at Hertford, in the County of Hertford, and Sentenced to be Transported to some of His Majestys Plantations in the West Indies; Who accordingly were putt on board the Shipp called the Anne of London, whereof one Thomas May is master, who undertook and engaged himself for their Transportation, Yet sett them on-shoare in or about the Downes, leaving them at liberty to goe whither they pleased; Which insolent demeanour being taken into Consideration; and it appearing to be a Matter of Contrivance and Combination between the said master and the persons before-mentioned; It was this day Ordered (his majesty present in Councell) That the high Shereif of the County of Hertford (now being) do cause the said [persons] to be apprehended and Secured, untill meanes of transporting them can be made, by some Shipping bound unto those parts.

Banishment by transportation was also a regular punishment for political rebels and Coldham’s book contains plenty from the ‘Monmouth Rebellion’ against James II & VII in 1685 and more again who rose in defence of his son James III ‘The Old Pretender’ (Jacobites) in 1715. These are just a few of the causes that may have forged our ancestors’ paths to America and beyond. In his article Fergus looks at bequests made by a Man of the Cloth, how he came by his money, how its legacy endured until the 1960’s in Aberdeen, and where such records can be found. CARIBBEAN SLAVERY AND EDUCATION IN ABERDEENSHIRE by Fergus Soucek-Smith of 'Old Scottish Genealogy and Family History' When I was applying to university in the mid-1980s, the then Scottish Education Department maintained a register of educational trusts that were available to provide support to prospective students. There were hundreds of such funds, some of them very specific. One of my university friends was given a significant amount of money each year from a variety of these funds, because of his surname and the small town where he was born. Most of these funds derived from bequests left over the years to various good causes. Kirk Session records often contain records of these legacies – often described as mortifications – as they were often tied to specific locales, and the Kirk Session was the obvious group to administer them. Aberdeenshire and the North-East in general are particularly well represented in such legacies, at least in terms of records surviving in the Kirk Session collections. There are a number covering large parts of the region, and many more covering individual parishes. Some legacies were intended to benefit the poor of the parish in the form of poor relief, but in keeping with the traditional Scots respect for education, many were intended to fund education in one form or another. The minutes of one such trust fund can be found among the Kirk Session records of Birse, in Aberdeenshire. [1] These minutes largely consist of details of payments made every six months to “the most indigent of the poor of the parish”, and are a handy source of information about some of the poorest people in this part of the north-east in the early 19th century. They even include a few payments to cover the cost of funerals of paupers, a useful source for genealogists given that the Old Parish Registers for Birse do not include any death or burial records. As is often the case for records of legacies and mortifications, the minutes include a transcript of the original deed or will establishing the fund. In this case, although the minutes begin in 1800, the fund was actually established in the will of Doctor Gilbert Ramsay, written in 1728. Dr Ramsay was an Episcopalian minister, originally from Birse. In 1686, he had arrived in the Caribbean as minister of St Paul’s, in Antigua. [2] By 1689, Dr Ramsay had moved to Barbados, where he became Rector of Christ Church. He remained at Christ Church for nearly forty years, before returning to the UK, “sojourning” in Bath, where he wrote his will. Presumably he was in Bath to partake of the waters, as in his will he writes that he is sick and weak in body, but (thanks to God) of sound and perfect disposition, mind and memory His first legacy is £4800 sterling to the “Corporation of New Aberdeen in North Britain, i.e. to the Provost, Bailiffs, Town Council, and governing members of the same city for the time being”, which is to be used to purchase land “as near to the City of New Aberdeen as can conveniently be purchased”. The proceeds from these lands are to be divided among various good causes. The “yearly Rent, Interest or Income” of £1000 is to be paid as a salary to a Pious, Learned, and well qualified Professor of Hebrew, Arabic and Oriental Languages, in the Marischall College of the said city of New Aberdeen, for the advancement of true learning, to the glory of God and the good of his Church. The second provision is that the proceeds from £2000 (of the £4800 left to the city of Aberdeen) should be used to provide a yearly pension to four hopeful, deserving young scholars, Masters of Arts, students of Divinity, which four students of Divinity conscionably elected I order shall be placed in said Marischal College of New Aberdeen to pursue diligently their Theological Studies there, for the Service of the Church … for the term of three years and no longer. The third provision of Ramsay’s will is a continuation of a Deed initially granted by him in Barbados in 1714, to provide for “four hopeful young men called Bursars, for ever to be educated in the knowledge of the Greek Tongue and Philosophy in the said Marischall College in New Aberdeen, during the space of four years and no longer.” This was to be funded from the proceeds of £800 of the legacy left to the Corporation. Ramsay did not forget his home parish. The “yearly rent, interest or income of five hundred pounds sterling” was to fund a salary to a pious, provident and experienced Schoolmaster well qualified to instruct the youth in the Parish of Birse … the place of my nativity … in the Principles of Religion, to read and write English, and to understand both Greek and Latin Before employing a schoolmaster, the proceeds were to be used to fund “building a schoolhouse in the most convenient place of the said Parish of Birse”. The remaining £500 of the legacy was to be given “to the order of the Reverend Ministers and Elders of the said Parish of Birse … to be forever by them conscionably and impartially distributed yearly among the poor of the said parish of Birse” on the first Monday of January and July each year. Patronage of the foundation was granted to Gilbert’s cousin, Sir Alexander Ramsay, Baronet and Laird of Balmain in Kincardineshire. Various other smaller legacies are given to “the poor Episcopal Clergy of Scotland”, to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the Scots Corporation in London, Balliol College, Oxford, and to various family and friends. Another £500 is left to Christ Church, Barbados to educate the poor youth of the parish. Reading all of this, you cannot help but wonder how an Episcopalian minister born in 17th century Aberdeenshire could have accumulated what was, for the time, a substantial sum of money. One clue is given in another provision of his will and my will is that all my slaves except my negroe man Robert here now attending me, be immediately sold after my death by my executor after named to such persons as will use them well tho’ at a cheaper rate than to others and to my said negroe man I give him his freedom from the day of my decease, and I will that he shall be taken care of and sent to Barbadoes at my charge, as soon as may be after my death and that the executors of this my will do pay him five pounds of that country money on his arrival at Barbadoes and likewise order, and appoint that all the money arising by such sale of my negroes shall be applied with the rest of my estate to pay off my legacies. Gilbert had evidently benefited significantly from the proceeds of slavery in Barbados. And his legacy continued to have knock-on benefits for a very long time. The Minute book of the Birse trust only cover the period 1800-1838, but the National Records of Scotland hold files on the Birse Mortification dating from 1886 [3] and 1889 [4] over 160 years after the bequest was made. Even that is not the end of the story: another record held by the NRS shows that it was not until 1961 that the trust fund was wound up.[5] For over 230 years, the people of Aberdeenshire benefited from an endowment established on the basis of profits from slavery. A number of prominent scholars are today attempting to unravel the ramifications of the proceeds of slavery on Scottish society. You have to wonder how many - if any - of the beneficiaries of this foundation were aware of where the money came from to fund their education. Sources:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy