|

All of the images of Manorial documents are the copyright of Berwick Record Office and by their kind permission were incorporated in examples to be used at Family Tree Live. They are not to be copied or reproduced in any way without express permission from Berwick Record Office . The transcriptions are my own and likewise may not to be copied or reproduced without my express permission. Many of my regular readers will have seen me refer to Manorial Records, but before now I haven’t taken the time to explain exactly what they are and the types of useful information they may contain. I had prepared some information sheets with examples on this subject for the Family Tree Live event in April, which sadly like all other events has been forced to cancel for this year. Now is perhaps an opportune moment to share a small part of that information . First, consider all the different types of records we use for family and local history research. With only a few exceptions, these resources served an administrative function and were created as a result of ever evolving administrative systems. Simply put; at the top there is central Government or prior to this the Crown; then devolved government, so within the United Kingdom the governments of Scotland, Ireland and Wales; then county or local government such as County Councils right down to a specific village Parish Council. The various systems, and who was responsible for their administration changed over time. A prime example is modern day ‘unemployment benefit’ which is controlled by central government, but its origins lie at Parish level with ‘Poor Relief’. Understanding how administrative systems have evolved throughout history will help enormously when searching for records in archive repositories. In addition to the above, another tier in the various systems of administration included the Manor. It is unclear exactly when the Manorial system came into existence, but it is thought to have been well established by the time of William I in 1066. At this time and throughout the Medieval period ALL land was owned by the Monarch, who made grants of land, which became Manors, to his followers making them Lords of the Manor. The land farmed ‘in hand’ by the Lord of the Manor was known as the ‘Demesne’ with other lands within the Manor rented out to tenants of which there were two types: free and unfree. Freehold. The freeholders or 'free tenants' of a manor held their land in perpetuity, frequently just paying a rent instead of providing a service to the Lord. Freeholders were largely unencumbered by the Manor but were still obliged to attend the Manor Court. Unfree Tenants. The unfree tenants of the Manor were known as Bondsmen or Villeins, and often provided a service such as a certain number of days labour to the Manor Lord in addition to a monetary payment. By the 16th century, payment by service had largely died out. This class of tenant became known as a ‘customary tenant’ and leases based on the ‘customs of the Manor’ were introduced. These comprised:

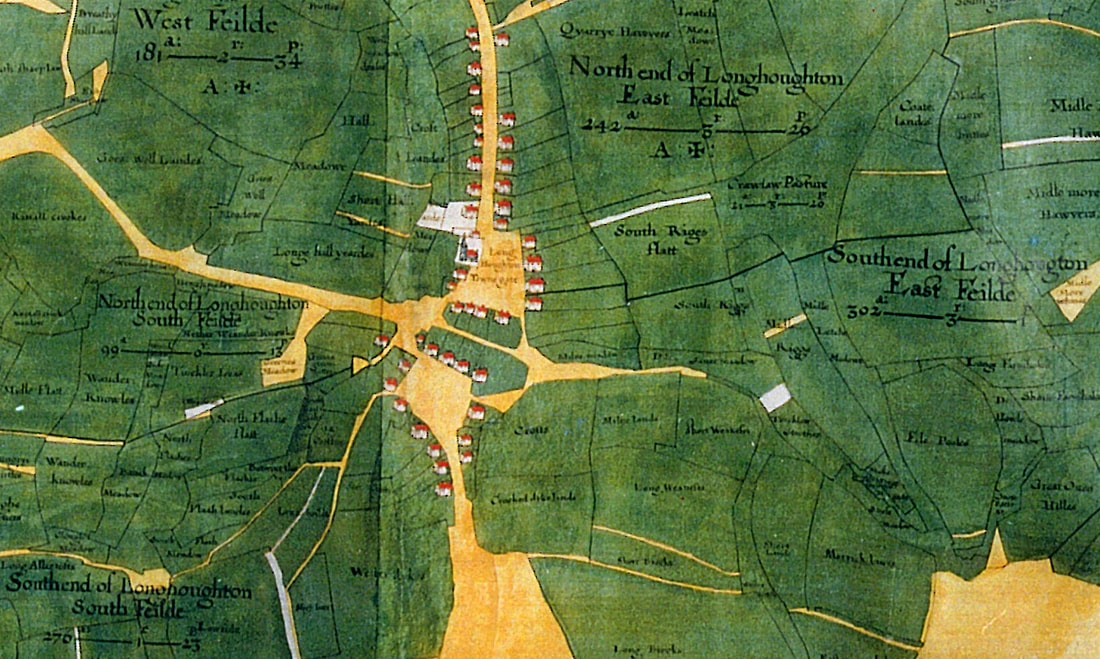

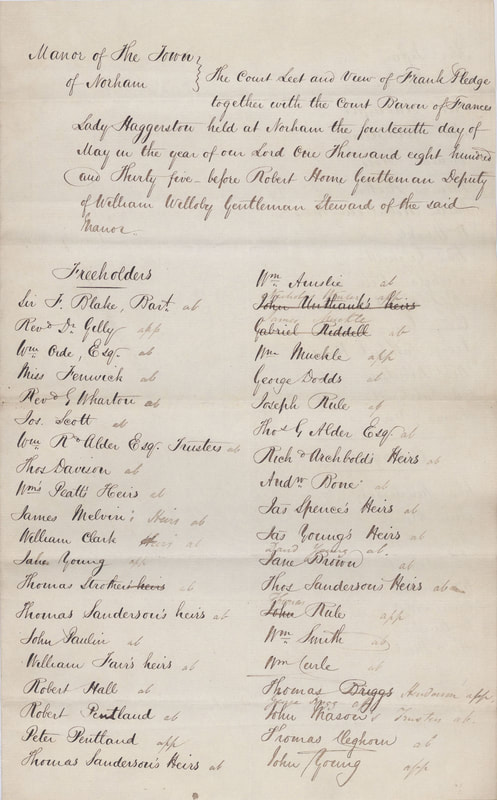

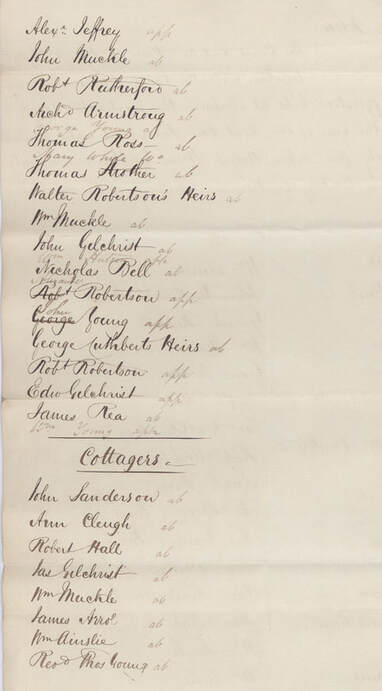

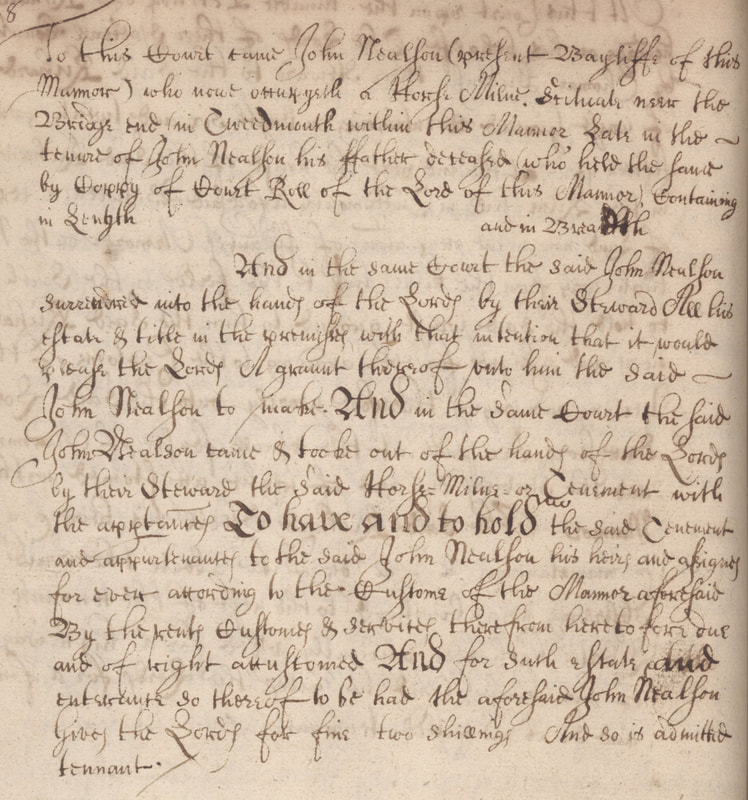

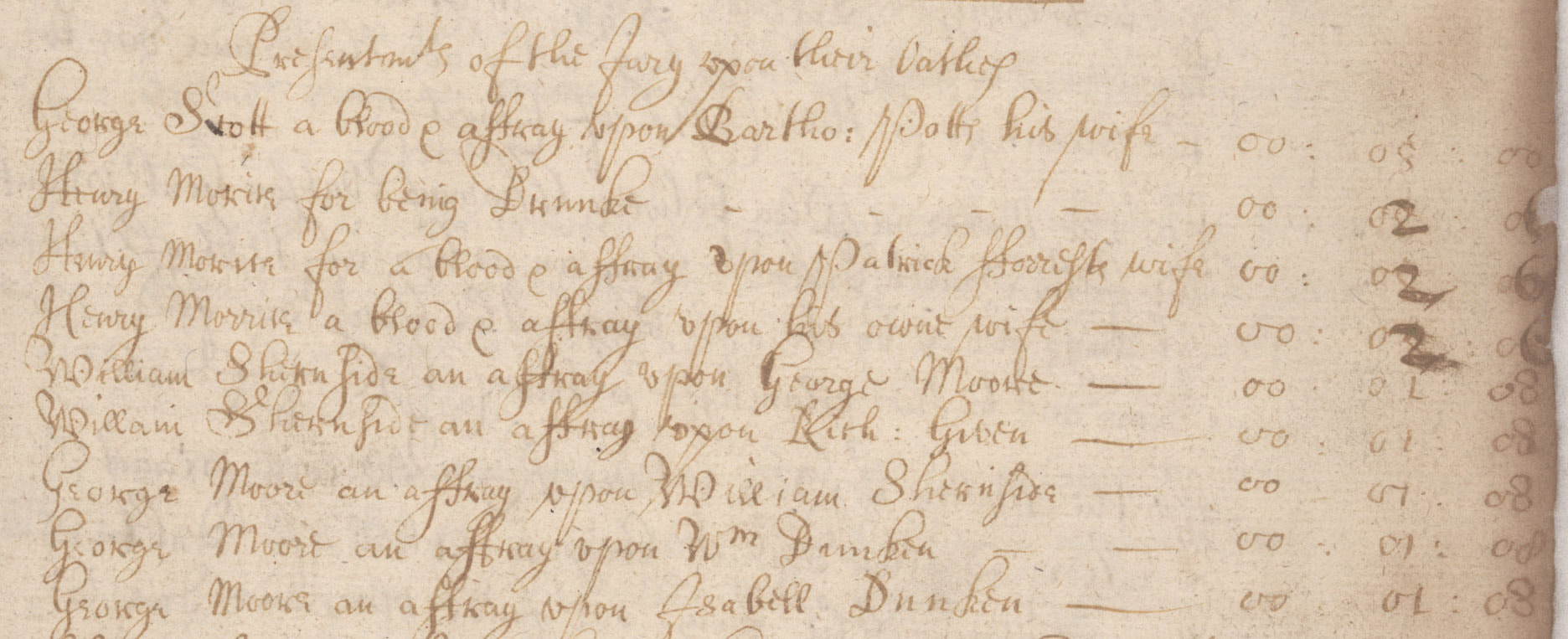

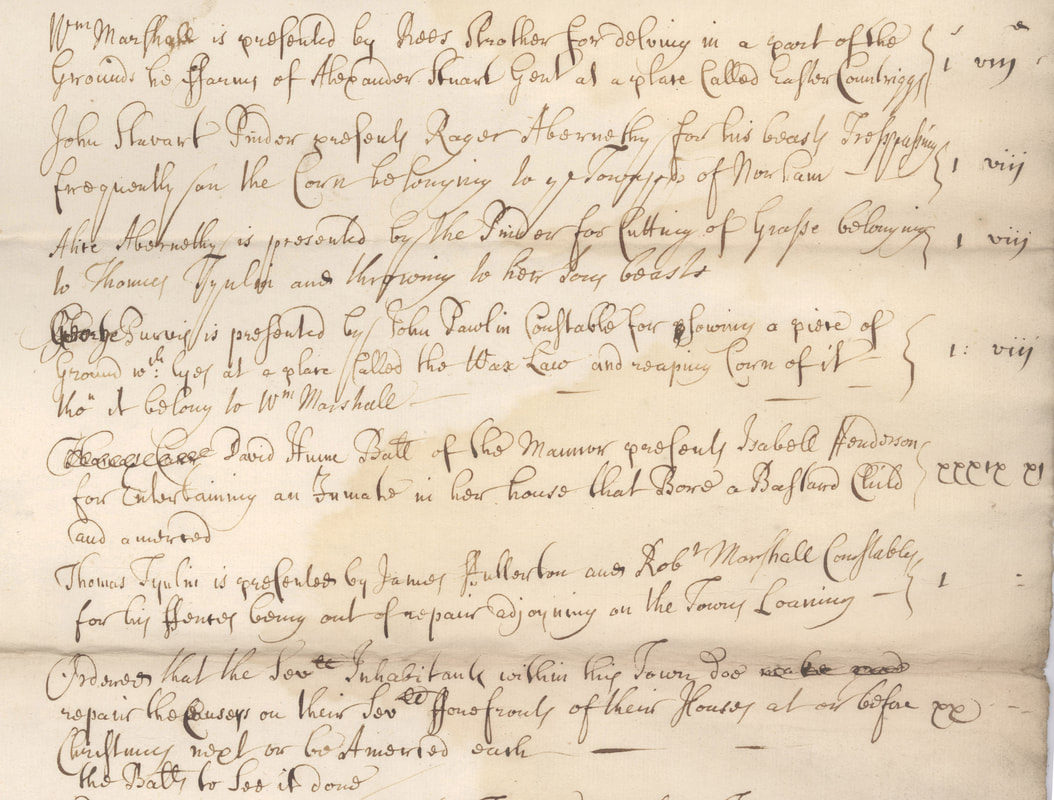

Unfree or Customary tenants were subject to the rules of Manor governing the maintenance of their properties. Failure to comply could result in a fine or even eviction. All tenants whether free, unfree or customary were obliged to appear in Court and absence without leave to be so resulted in a fine known as an ‘amercement’. Those with a valid reason for non-attendance were charged a nominal fee known as an ‘essoin’. The tenants' names appeared in the Court ‘Call Books’ which were often annotated with either ‘amerc’ or ‘ess’, or in later documents 'app' or 'ab' to indicate whether they were present or absent at the meeting of the Court. It is worth remembering that ‘The Manor’ differed from an ‘Estate’ as it had the right to hold a Court, and that an ‘Estate’ may have contained several different Manors. Whilst the Manor was predominantly a rural entity it was not exclusively so, nor was one village or town included in a single Manor. For example, Norham had two Manors: Norham Town and Norham Castle. Below is an extract from the Call Book for Norham Town in 1835 In this later example from 1835 (where the names are easy to read) the abbreviations used are: app = appeared ab = absent All matters relating to the transfer of property within the Manor were heard at the Manor Court and entered in the Court Rolls. There were two types of Court which dealt with matters concerning land; The Court Baron dealt with freeholders and the Court Customary which dealt with land matters for other tenants. In practice these two courts were regularly merged, and business was conducted collectively by the Court Baron and often include admittance to land and its surrender. These courts met frequently, in some cases every fortnight, although their regularity started to dwindle in the late 18th early nineteenth centuries. Admittances and surrenders were usually accompanied by a ‘fine’ or fee payment. Where they have survived these documents contain valuable sources of information for the family historian. To this Court came John Nealson (present Bayliffe of this Mannor) who nowe occupyeth a Horse Milne Situate near the Bridge end in Tweedmouth within this Mannor Late in the tenure of John Nealson his Father deceased (who held the same by Copy of Court Roll of the Lord of this Mannor), Containing in Length and in Breadth And in the same Court the said John Nealson surrendered into the hand[es] of the Lord[es] by their Steward All his estate & title in the premises with that intention that it would please the Lord[es] A graunt thereof into him the said John Nealson to make. And in the same Court the said John Nealson came & tooke out of the hand[es] of the Lord[es] by their Steward the said Horse-Milne or Tenement with the app[ur]tan[en]ces To have and to hold the said Tenement and appurtenances to the said John Nealson his heirs and assigns for ever according to the Customs of the Mannor aforesaid By the rents Customs & services therefrom heretofore due and of right accustomed And for such estate and entrance so thereof to be had the aforesaid John Nealson Gives the Lord[es] for fine two shillings And so is admitted tennant. Other payments that may be unfamiliar were; the ‘Heriot’, a fee that was payable on the death of a tenant, and the ‘Merchet‘ a fee payable for the permission for a tenant’s daughter to marry. In addition to land matters some manors could hear minor criminal cases such as affray, nuisance, failure to maintain property, trespass and debt at a ‘Court Leet’. The Court Leet was often combined with the View of Frankpledge, whereby tenants swore to uphold the Kings Peace. One particularly bloody affray was heard at the Tweedmouth Manor Court in May 1661 Presentments of the Jury upon their Oathes George Scott a blood & affray upon Bartho[lomew] Potts his wife 00:08:00 Henry Morise for being Drunke 00:02:06 Henry Morise for a blood & affray upon Patrick Forriste wife 00:02:06 Henry Morise a blood & affray upon his own wife 00:02:06 William Shirnside an affray upon George Moore 00:01:08 William Shernside an affray upon Rich[ard] Given 00:01:08 George Moore an affray upon William Shernside 00:01:08 George Moore an affray upon W[ilia]m Dunken 00:01:08 George Moore an affray upon Isabell Dunken 00:01:08 An example of the typical matters heard at the Manor Court of Norham Town in 1706 W[illia]m Marshall is presented by Rees Strother for delving in a part of the Grounds he Farms of Alexander Stuart Gent[leman] at a place Called Easter Countriggs 1s viij d John Stewart Pinder presents Roger Abernethy for his beasts Trespassing frequently on the Corn belonging to the Town of Norham 1s viij d Alice Abernethy is presented by the Pinder for Cutting of Grasse belonging To Thomas Tynlin and throwing to her Sons beasts 1s viij d George Purvis is presented by John Pawlin Constable for Sowing a piece of Ground w[i]th lyes at a place Called the Wax Law and reaping Corn of it tho’ it belongs to W[ilia]m Marshall 1s viij d David Hume Ba[il[i]e of the Mannor presents Isabel Henderson for Entertaining an Inmate in her house that Bore a Bastard Child and amerced xxxix s xj d Thomas Tynlin is presented by James Fullerton and Rob[er]t Marshall Constables for his Fences being out of repair adjoining the Towns Loaning 1s Ordained that the Sev[era]ll Inhabitants within this Town doe repair the Causeys on their Sev[era]ll Forefronts of the Houses at or before Christmas next or be Amerced each xx s The Ba[i]ll[ie]s to See it done NB. Pinder = kept the manorial pound/pinfold, Inmate= a lodger or subtenant which was severely fined at 39 shillings and 11 old pence, just under £2, approximately £214 as at 2017. From the Tudor period onwards much of the Manor’s administration was absorbed in the new systems of local administration and powers transferred to the Justices of the Peace, parish and town officials. Common and statutory law began to replace customary law rendering the judicial role of the Court Baron obsolete. Therefore, by the 17th century, the main responsibility of the court was to deal with the transfer of land and minor cases of debt under 40 shillings. This function and the holding of the Court Baron continued right up to the 1920s when copyhold tenure was abolished. (It was this transfer of Copyhold to Freehold that George Aynsley Smith undertook in his capacity as Clerk to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in Durham at the Halmote Court.) In addition to their value to family historians, Manorial Records are a mine of information for local historians too. Just a small example is some of the field names I remember as a child, such as The Riggs, [High] Mill Lands and Eels Pools appear on an old map for the Manor of Longhoughton at the top of this blog. The records for Longhoughton Manor date back to 1474. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/c/F282364 The surname Elder that appeared on the Alnwick Muster Roll of 1514 is still associated within living memory of the Village today. https://www.flodden1513ecomuseum.org/project/the-campaign/31-the-alnwick-muster-roll (If you would like a transcription of any part just let me know!) How to find a Manor in the Manorial Documents RegisterTo find the archive repository that holds the Manorial records which may be of use to you, they can be found in the Manorial Documents Register online at The National Archives. Here is the link to the page containing the surviving records for Manors in Northumberland. ttps://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/results/c?sf=textstman&_ocn=Northumberland&_naet=M&_st=mdrc Clicking on the records of the individual Manor will give the name of the repository that holds the records. Many of Northumberland’s records are held at Alnwick Castle, which as it is a privately funded archive is neither straightforward (but not impossible) nor at £55 per day, cheap to visit. https://www.alnwickcastle.com/_assets/media/editor/Archives_doc/2017-03-09-guide-to-searchers.pdf The records for Durham have not yet made it to the online register, but as a work in progress will be coming soon. Other Useful LinksAside from the records mentioned above, and rather than list them all here, Lancaster University has an excellent website which although its focus is the Manors of Cumbria, it contains a wealth of information covered in far more detail than I have here. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/manorialrecords/manors/classes.htm An extensive Glossary of unfamiliar terms and phrases in Latin, can be found at the University of Nottingham https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/manorial/glossary.aspx

1 Comment

|

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy