|

When faced with an information ‘void’ it is understandable how and why researchers sometimes jump on ‘facts’ pertaining to familial connections freely available on the internet or published elsewhere. There are many reasons why these ‘blackholes’ may arise; nonconformity, a lack of heritable property or Wills, lost or damaged records to name but a few. Whichever way, if our ancestors were ‘ordinary’ law abiding folks they can often become tricky, if not impossible, to trace with any degree of certainty in the period before the Census and Statutory Registration. There are, however, other measures that can be tried before resorting solely to the research of others! Broadening the net to catch as many potential relatives as possible and investigating their connections is just one way to ‘ring fence’ your own ancestors. I think of this as gaining access to the required information through the ‘side door’. Then, as now, family connections and the principle of ‘who’ rather than ‘what you know’ often played a pivotal role. Taking a closer look at fellow passengers, communicants of a specific church, or trades, occupations and residents in particular community may just pay dividends. Johnston Case StudyThe case in question is the search for the parentage of Andrew Johnston allegedly born at Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1766 for whom no baptism information has been identified, most probably due to the family’s nonconformity and gaps in the records. Returning to the other families who emigrated to Australia alongside the Johnstons aboard the Coromandel in 1802, the researcher is quickly bombarded by a surfeit of conflicting information from a variety of sources. For example:

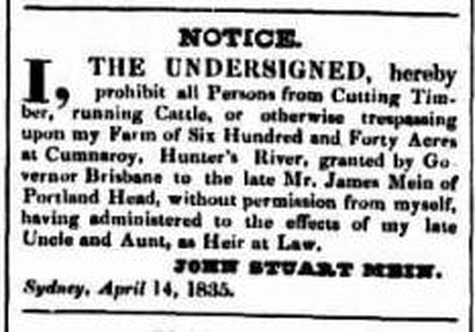

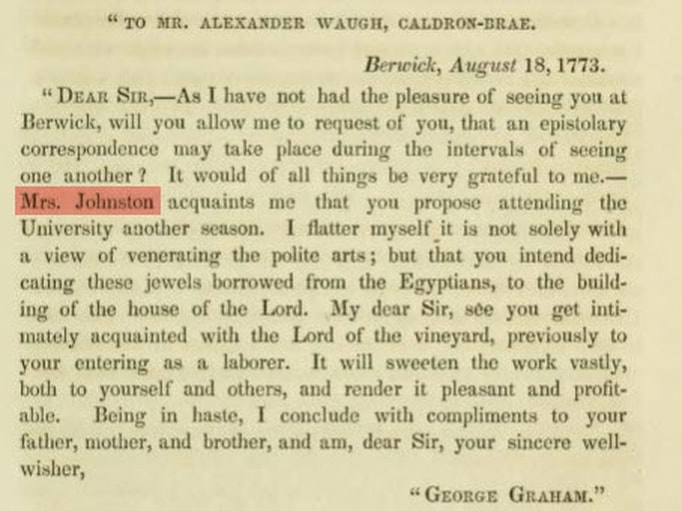

Using DNA for early ancestor searchesFor this latter dilemma, science can play a determining role if lucky enough to have a direct male Johnston descendant to test and a bank of well documented Y-DNA to compare it to. Broadening the search can help identify possible family groups with suitable male descendants to potentially approach regarding Y-DNA testing. It will likely involve a bit of detective work tracing family lines but might just pay dividends if the trail leads back to a known parish, community, or geographical area. When searching for suitable descendants it is important to watch for breaks in the male line of inheritance. There are many reasons male lines can be broken but one that is often overlooked relates to inheritance. If a title or inheritance for some reason passes through a daughter or female line and surnames are changed to accommodate it, the historic line of Y-DNA has been broken and will no longer reflect the original blood line. If looking for a potential connection to a ‘landed’ family this is worth investigating to ensure the Y-DNA carried is in fact that of the surname expected! It is a big ask for autosomal DNA (atDNA) to provide definitive answers at extremes of generational distance. Remember, due to the way autosomal DNA is transmitted, (and lost) with each generation that passes there is no guarantee we will have inherited any from our ancestors beyond 3rd great grandparent level. Any matches that do exist are going to be small, if indeed they exist at all. Furthermore, if a search focus is narrowed to only one ancestor it is easy to lose sight of the fact that, if our line is free of cousin marriages, we have 64, 4th great grandparents and 128, 5th great grandparents. That is a lot of individuals from whom we might, or might not, have inherited autosomal DNA! Extreme care should be exercised when attributing DNA matches at this historic distance, particularly if a large amount of DNA is shared between testers or if several different ancestor families lived in the same geographical area. For example, Sprouston in Roxburghshire is synonymous with a branch of my paternal line ancestors, yet the first 5 atDNA matches that come up under the place name search are on my maternal, rather than paternal line. Broaden the ancestral searchIt is all too easy to fixate on a single ‘troublesome’ individual when perhaps the net should be cast wider to encompass siblings, cousins and other more distant family members. This unfurling of the family tree is essential if looking for clues amongst DNA matches.  The Mrs Johnston referred to in this extract from Rev Alexander Waugh's Memoirs cannot be his Grandmother, is not his only sister, and yet appears to be well acquainted with Alexander’s plans for study etc. Therefore, it is concluded that the lady to whom Mr Graham refers is a ‘relation’ of the Rev Alexander and quite possibly the mother of Andrew Johnston born at Berwick in 1766. Whilst the ‘devil’ is often in the detail, more general patterns, particularly those of movement and relocation, can often hold vital clues and can be found in traditional paper-trail sources. When combined with DNA results, the armoury in a genealogist’s toolbox is significantly strengthened. Possible Connections between Johnston, Mein & Turnbull FamiliesWith a broader search in mind, looking at the pedigrees of fellow travellers aboard the Coromandel may yet yield some further clues. It is known that many of the individuals hailed from the same geographical area of the Scottish Border and North Northumberland and were united by their strong Presbyterian beliefs. It is therefore not unreasonable to speculate that some familial connection may also have existed. A generally held belief amongst researchers of the Hawksbury Settlers is that John Turnbull was not only related to fellow Coromandel passengers, James and Andrew Mein but also the Johnston family. The theoretical relationships between the Turnbull, Mein and Johnston families is discussed by Albert Turnbull in his 2018 book ‘The Turnbull Pedigree’. This potential connection is certainly plausible and has been evidenced to a degree by an old family Bible bearing what is believed to be John Turnbull’s signature as a child, alongside that of his mother Margaret Mein. There is, however, a lack of clarity to the evidence as presented in the book that makes the theoretical paper-trail somewhat challenging to follow or replicate. It appears the Bible may be the only source of baptismal information for several of the children of William Turnbull and Mary/Margaret Mein. which again raises the possibility of nonconformity. A possibility that has not been explored by the book’s author. It would be interesting to test Turnbull’s relationship theory against the information pertaining to the inheritance of James Mein’s estate. A nephew, John Stuart Mein, travelled from Scotland in 1834 to claim his inheritance on the death of his aunt in 1833. Clearly if Margaret Mein was a relative of James, her Turnbull offspring in Australia (John) appear to have been passed over in favour of those who had remained in Scotland. Once again there appears to be a degree of conflicting information to wade through from various sources, not least the year of James Mein’s birth recorded as both 1741 (which would have made him of an age with John Turnbull himself, and aged 61 when he left for Australia) and 1761 some 20 years later! Turnbull’s same hypothesis refers to Janet Johnstone the wife of Nicholl Turnbull having been born at Earlston in 1677. As the Earlston records have not survived from this date knowing the source of this information would also be most helpful. It may eventually prove to be the case that she was the Janet Johnston baptised at Gordon in August the same year to a William Johnston farmer at Hexpath. Although William Johnston of Hexpath has yet to be firmly placed within the Johnston family tree, it is thought likely that a familial relationship existed between him and Margaret Johnston, mother of the Rev Alexander Waugh and her known connections at East Gordon. As the Turnbull Pedigree also claims that the young John Turnbull spent time at Banff Mill, Sprouston, it put me in mind of my own, again sadly neglected, Turnbull connections. A paternal 5th great grandmother, Christian Turnbull, was born in 1717 at Easter Softlaw Farm, Sprouston, where her father John Turnbull was tenant. It did not take me long to remind myself why I give this early branch of the family a wide berth! There were simply so many of them in Sprouston parish; John and George Turnbull tenants at Easter Softlaw, James Turnbull tenant in Nottylees, Robert Turnbull tenant in Lurdenlaw and another James Turnbull tenant in Lempitlaw Eastfield. Some 85 years later from the Militia Lists of 1801 some of these Turnbull families were still resident at Lurdenlaw, Lempitlaw and Lempitlaw Eastfield. In my brief revisiting of this branch of Turnbulls and indeed the other entries in the Sprouston register, no connection between a Turnbull and Banff Mill was apparent. Indeed, a re-reading of this chapter of the Turnbull Pedigree left me somewhat cold. ‘Banff Mill is a tiny village on the river Teviot, opposite Kelso/Sprouston, but in the parish of Berwickshire which is renowned for its poor or missing records’[1] The efficacy of the Berwickshire records and record keepers aside, the number of errors packed into this single sentence must be a record!

Sadly, this has rather left me questioning the credibility of other conclusions that have been drawn within the relevant chapters of this book. By the time of a potential sibling’s baptism in 1752 the putative parents were living at Overmains, close to Kennetsideheads in Eccles Parish, not as the author would suggest close to Banff Mill. This surely makes any ‘memory’ or link John may have had to Banff Mill from birth to the age of 4 rather tenuous? With time at a premium the Turnbull connection has been left in abeyance for now. Johnston Baptisms at Wells St Church 1775-1826 It is also my experience that delving deeper into available records in areas to which a family has relocated often provides evidence of siblings or other connections. With this in mind the records of Wells St Church in London between 1775 – 1826 were trawled for further clues pertaining to the Johnston family. (It should be noted that as a nonconformist church it was unable to host weddings under the Marriage Act of 1753. Nonconformist couples wishing to marry in England had to do so in an Anglican Church until the introduction of Civil Registration in 1837.) In 1782 Wells Street Church passed into the pastoral care of Rev Alexander Waugh, a known and established relative of Andrew Johnston. This was also the first year the number of baptisms at Wells Street achieved double figures at a total of 12. By the year 1784 the number of baptisms had more than doubled to 27. From this point forward the numbers steadied in the mid- 30s with a few years rising above 40; the highest number of baptisms recorded was 48 in 1815, and the lowest just 19 in 1808. Thus, it can be concluded there were, very approximately, 50/60 couples of child-bearing age amongst the congregation during this period. The occupational and other information provided by the entries also makes interesting reading.

NB. Only baptisms which took place at Wells St are listed. 1. Andrew Johnston and Hamilton Bruce Name Baptism Date Parents Names Parish of Abode Occupation John 6th Oct 1811 Andrew & Hamilton Johnston St Marys Hornsey Carpenter Hamilton 17th Mar 1814 Andrew & Hamilton Johnston Hornsey Implement Maker Janet 26th Sep 1816 Andrew & Hamilton Johnston Hornsey Ag Implem. Maker Andrew 9th Aug 1818 Andrew & Hamilton Johnston Hornsey Ag Implem. Maker This Andrew and his wife Hamilton Bruce have been traced back to Berwickshire. Their two eldest children Mary 1806 and Margaret 1809 were baptised at Chirnside. From the 1851 census Andrew’s date of birth was circa 1780/81 and the place is recorded as ‘Berwick, Scotland’. Berwick is often mistakenly referred to as Scotland in the southern census records, but equally, Berwick may also mean Berwickshire. Andrew died in 1852 and left a Will. 2. Andrew Johnston and Elizabeth Fairbairn Name Baptism Date Parents Names Parish of Abode Occupation Andrew 25th Feb 1812 Andrew & Elizabeth Johnston Marylebone Carpenter Elizabeth 1st Feb 1814 Andrew & Elizabeth Johnston St John Westminster Carpenter Janet 29th Feb 1816 Andrew & Elizabeth Johnston St Johns Westminster Builder James 20th Nov 1818 Andrew & Elizabeth Johnston All Saints, Isleworth Architect Margaret 20th Nov 1818 Andrew & Elizabeth Johnston All Saints, Isleworth Architect This Andrew rose quickly from Carpenter to Builder then Architect. He and Elizabeth were not the easiest to trace but his line has been validated back to Roxburghshire and parents Patrick/Peter Johnston and Janet Dods who were married at Stichill 25th May 1771. Compeared Patrick Johnston And Janet Dods both in this Parish & craved proclamation in Order to Marriage They produced Patrick Jeffrey Cautioner for the man & Nicol Dods for the woman [2] The family became dispersed when Andrew died circa 1833 and is of particular interest due to the name ‘Waugh’ being adopted by daughter Margaret in later life. It is also believed there are living male descendants on this line with whom we would be particularly keen to make contact. Whilst it is very early days, it is hoped this second line of enquiry into Johnston births at Wells St. may tighten the ring fence around Andrew Johnston’s potential parentage still further. If you believe you are connected, to either of the Andrew Johnstons mentioned above or indeed the Andrew Johnston who emigrated to Australia aboard the Coromandel in 1802 we would love to hear from you. [1] Albert Turnbull, The Turnbull Pedigree,

https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Turnbull_Pedigree.html?id=orpUDwAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y p.32 [2] Scotlands People, Marriage Patrick Johnston & Janet Dodds 1771 ScotlandsPeople_OPR808_000_0020_0235Z

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy