|

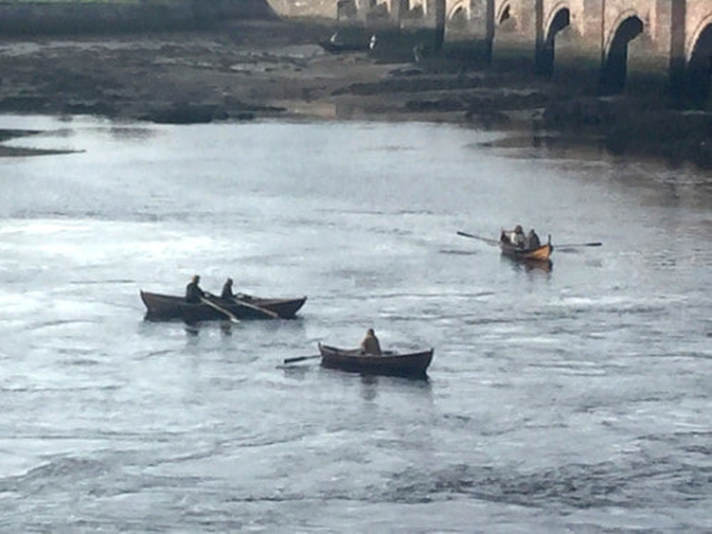

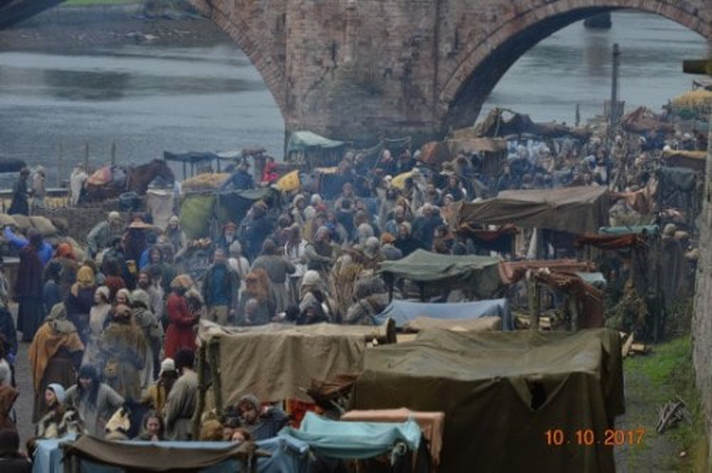

Last month (October) saw film crews descend upon Berwick upon Tweed filming scenes from the first of what is outlined to be a ‘trilogy’ into ‘A true David v Goliath story of how the great 14th Century Scottish 'Outlaw King' Robert The Bruce used cunning and bravery to defeat and repel the much larger and better equipped occupying English army’. Great and popular viewing it will no doubt prove to be, but please don’t be fooled into taking it as a History Lesson. Take ‘Braveheart’ for example, riveting cinema - but with ‘18 historical inaccuracies in the first two and half minutes’ spotted by Dr Sharon Krossa, who likened it to a ‘fantasy’, these productions from an historical point of view, really should be taken with a large shovel of sodium chloride. Needless to say in the case of Berwick and 'The Outlaw King' I was not the only one tempted to reach for my soapbox to set the matter straight before a new visual history becomes 'lore', but as local historian Jim Herbert of Berwick Time Lines is far better versed in the subject than I, here is his recent article which explains all. THE OUTLAW KING COMES TO BERWICKAnd so the Hollywood/Netflix circus has been in town to film The Outlaw King, starring Chris Pine, Florence Pugh, and James Cosmo among others. One star that sadly may not, for many, shine as brightly is Berwick-upon-Tweed. Yes, its great fun watching the filming this week and we hope that it will bring some much needed extra income to the town, but the filming locations—the Quayside and the Old Bridge—are the stunt doubles for Glasgow and London Bridge. This is a great shame as Bruce had an important part in Berwick’s medieval past. Let us examine his role. Early DaysOne of many misconceptions is that the Bruce family were Scottish. They started off, like so many of the nobility in Britain as Norman; the name comes from Brix in Normandy. They acquired, and fortified, Hartlepool after the Norman Conquest but were later grated Annandale (in modern Dumfries and Galloway) by King David I of Scotland in 1124. The story starts in 1286 with the death of King Alexander III and the ensuing Great Cause of 1291. Of the noblemen claiming the Scottish throne there were only two real contenders, John Balliol and Robert de Brus, 5th Lord of Annandale. (As with so many families, the first names are handed down through the generations which can be confusing. This Robert Bruce was the grandfather of our Robert the Bruce and future King Robert I, who was born in 1274.) The Balliols, who were allied to the Comyns, and Bruces had been spoiling for a fight for some time; John II “Black” Comyn had been a third possible contender for the Scottish throne. In 1295 after members of the Scottish nobility refused to pay homage to Edward I, among them, the Bruces. Following Edward’s demands of the Scots for military assistance, the Scots formed what became known as the Auld Alliance with France. The burgesses of Berwick, the principal Scottish Royal Burgh, latterly signed up to this alliance. Watch out Bruce - He's Comyn For YouMeanwhile, Edward was attending to “diplomatic discussions” in France which were proving awkward to say the least. While away, the Scots kept their side of the Alliance and made incursions into the north of England. Annandale was attacked by King John (Balliol) and given to John Comyn, Earl of Buchan; the Bruces, evicted from their estates in south-west Scotland sought the safety of England and sided with Edward I. Sensing trouble ahead, Edward I appointed Robert the Bruce’s father, another Robert de Brus, 6th Lord of Annandale, as governor of Carlisle Castle. On 26 March 1296, Easter Monday, seven Scottish earls led by Comyn attacked Carlisle. This was to be the first act of aggression in the first Wars of Scottish Independence. However, it was not so much an attack on the English than the Comyn family taking on the Bruces. It was the last straw, however, and led to Edward returning to England and commanding his army muster in Newcastle and marching north. Edward laid waste to Berwick on Good Friday 30th March. Balliol was deposed as King of Scotland. And so to William Wallace. After his Battle of Stirling Bridge on the 11th September 1297, Wallace was appointed Guardian of Scotland, the first to hold the post during the second interregnum. His men harried the north of England down to Hexham. The English basically abandoned Berwick and one of Wallace’s men, Haliburton, took Berwick and kept it until Wallace returned north in early 1298 after trashing Northumberland. In turn, the Scots abandoned the town by the next Spring pre-empting Edward’s wrath. Wallace was defeated at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 and resigned as Guardian. Bruce and John III “Red” Comyn were appointed joint Guardians of Scotland in his place but Bruce resigned in 1300. He, in turn was replaced by Sir Ingram de Umfraville and William de Lamberton. In 1301, Edward launched his sixth invasion of Scotland after which in 1302 many of the Scottish nobility, including Bruce, swore fealty to him. In 1303, Edward launched yet another attack north of the border reaching as far north as Aberdeen. Now, all of Scottish nobility surrendered to Edward, save Wallace, who was eventually captured near Glasgow in 1305 and met a very sticky end. Both Comyn and Bruce still held dearly their claims to the Scottish throne and it was at a meeting between them on 10 February 1306 at the Chapel of the Greyfriars Monastery in Dumfries that Bruce accused the Red Comyn of treachery and murdered him. Bruce then began his claim to the throne through aggression with a successful attack on the English garrison at Dumfries Castle, after which his long time ally Robert Wishart, the Bishop of Glasgow granted him absolution. Nevertheless, he was excommunicated. Some English records suggest that the murder was premeditated and that Edward wrote to the Pope asking for Bruce’s excommunication. Six weeks later, Bruce was crowned at Scone near Perth by Bishop Lamberton. Bishop Wishart who had hidden the Scottish regalia was amongst those in attendance. It was traditional that MacDuff, the Earl of Fife performed the ceremony. In the absence of any of the male MacDuffs, Isabella MacDuff claimed the right to perform the ceremony. She arrived at Scone a day late and so a second ceremony was performed. Edward moved north yet again. He defeated Bruce on 19th June 1306 at the Battle of Methven. Bruce’s wife and other ladies of the court were sent to his brother’s castle at Kildrummy for protection. Bruce and his few followers fled. Alas, there was no safety to be had at Kildrummy. Bruce’s wife Elizabeth, his sisters Christina and Mary, and Isabella MacDuff were captured; his brother, like Wallace before, was hanged, drawn and quartered. It was for her part in the crowning of Bruce that Isabella was held prisoner at Berwick Castle. Bruce was declared an outlaw. The Bruce Comes to BerwickEdward I died in 1307. His heir, Edward II was a weak ruler, from whom Bruce allegedly said it was easier to gain a kingdom than a foot of land from his father. On 6th December 1313, Bruce made his first attempt to take Berwick. It is described in the Lanercost Chronicle: “In the night, coming unexpectedly to the castle, he placed ladders against the wall and began to ascend. Unless the loud barking of a dog had made known the arrival of the Scots, he would quickly have taken the castle as well as the town. The ladders, curiously made for the purpose of scaling, were left here, and our men have hung them over the pillory as a public show. So this dog saved Berwick as formerly the cackling of the geese saved Rome.” By this time Bruce had recaptured most castles from the English. Edward II’s response was to assemble a vast army, complete with provisions for the campaign, at Berwick. This army is said to have consisted of 60,000 foot and 40,000 horse; 3,000 of the latter are said to have been horsemen in complete armour. The King met the army here. Never had such a vast number been mustered in Berwick before of since, but numbers alone do not always bring victory; rather, it ended in a crushing defeat at Bannockburn from whence Edward returned to Berwick alone. Emboldened, by his success, Bruce attempted another assault on Berwick. The Lanercost Chronicle again: “Within the octaves of the Epiphany, 15th January, 1316, the King of Scotland, with a great army, came secretly to Berwick, and under brilliant moonlight made an attack by land and by sea in skiffs, hoping to have entered the town on the river side between the Bridge House and the Castle, where the walls were not yet built. But by means of watchmen and others through the noise of those attacking they were repulsed, and a certain Scotch soldier, Sir J. de Landels, was killed, and Sir James Douglas with difficulty escaped in a small skiff. And thus the whole army was put to confusion…” The victory against the Scots was a Pyrrhic one. The town was in dire straits, as was all of Northern Europe, gripped by the Great Famine. Poor harvests due to cold, rainy summers were taking their toll. Letters of the day from the Warden, Maurice de Berkeley give a vivid impression of life in the town for the English garrison: “Tells [Sir William Ingge] no town was ever in such distress as Berwick short of being taken or surrendered. The garrison are deserting daily, and there are none left in the town, save only such of the garrison of the castle as are not slain or dead of hunger. If the town is lost, the blame will rest on him as one of the King’s chief councillors. Whenever a horse dies in the town the men-at-arms carry off the flesh and boil and eat it, not letting the foot touch it till they have had what they will. Pity to see Christians leading such a life. If he would save the town, prays him to send assistance quickly.” To the king: “The burghers are deep in debt, and his men are dying of hunger on the walls. He has supplied them out of his own means while he had any. The town was never in such a state, as he has often told the King; but he sees clearly that no order of the latter is obeyed. Whatever his ministers may say to the contrary, there has not come to Berwick, either in money or provisions, since he arrived there, more than £4000, and there are ten weeks short of the year. Of the 300 men-at-arms enrolled, only 50 can be mustered mounted and armed, the rest of the horses being dead, and the arms at pledge for the owners sustenance. He has not had a penny of his own pay since Michaelmas. Begs him to take thought for them and the town, for if he loses it, he will lose all the north, and they their lives. Begs another warden may be appointed, as his term expires a month after Easter, and he will remain no longer. Thinks no attention has been paid to his former letters.” The mayor, bailiffs and community of Berwick to the King. Tell him that the town is in great danger, as there are only provisions for one month… Sir Robert de Bruys will be at Melrose before Ascension Day with all his force, and do his utmost, they fear, to annoy them by treason or otherwise…” The town was in disarray with a power struggle between the burgesses and the garrison. The Mayor, Walter de Goswik, had “been very much harassed by the keepers of the town appointed by the King”. James Douglas, one of Bruce’s new allies and whom had been part of the unsuccessful 1316 raid, gained intelligence of this confusion. He and Bruce amassed a new army. Contemporary records tell us that Douglas believed he could gain the trust of one of the garrison and bribe him to assist the Scottish cause. That man was Peter de Spalding. The Scottish poet Barbour records that Spalding: “…was annoyed at the Governor’s ill-will to the Scotch in the town, and covenanted with Bruce through Marshal Keith to deliver up the town to him if he drew to it during night, and at the Cowgate when it was his turn to watch.” This he did. Douglas and his men scaled the walls and hid overnight; remember, at this time the Parade/Ravensdowne area had no buildings on it, save for some stores—the King’s Garners—and the old Parish Church. In the morning, all hell broke loose as the Scots plundered the town. After a siege of six days, the castle too capitulated and King Robert strolled into the town. As for Peter de Spalding? His reward for assisting the Scots was not the promised £800 (something in the order of £300K–£400K today) but execution. The following year, Edward attempted to retake the castle but was thwarted by the efforts of the Flemish pirate-cum-siege engineer, John Crabbe. In retrospect, this was a last hurrah for the Scots. The town finally fell after the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 bringing to an end the last time the Scots held Berwick for any great length of time. However, the one last thing that Bruce gave to Berwick before his death in 1329 was the completion of the medieval walls begun by Edward I in 1296. BraveheartSince the filming began, I have been asked one or two questions regarding the mythology that surrounds 'The Bruce'. One story in particular that I was asked about was one that the correspondent’s teacher had passed on years ago; that Bruce’s heart had been buried in Berwick. Bruce died in 1329 near Dumbarton, possibly of leprosy. Robert’s final wish reflected conventional piety, and was perhaps intended to perpetuate his memory. His last regret was not partaking in any crusade. After his death his heart was removed, placed in a silver casket, and taken by Sir James Douglas on a crusade to help Spain regain Granada from the Moors. Sir James and most of the Scottish contingent were killed but his body and the casket were recovered and returned to Scotland. The casket was buried at Melrose Abbey. It was discovered in 1920 and then rediscovered in 1996 when it was forensically examined and deemed to have held human tissue of the correct age. It was reinterred in 1998. Nothing to do with Berwick. However, Robert did arrange for perpetual soul masses to be funded at the chapel of Saint Serf, at Ayr and at the Dominican friary in Berwick (near the Bell Tower), as well as at Dunfermline Abbey. It is ironic that arguably the one accurate thing the 1995 Mel Gibson film Braveheart portrayed (the “Braveheart” in question being Bruce’s and has nothing to do with Wallace) was Bruce’s ambivalence, siding with the English against Wallace. Glasgow GoofsNow, I’m no historian of Glasgow and I stand to be corrected, but some quick research reinforces my original thoughts regarding Berwick Quayside portraying the Port of Glasgow: would there have been a port in Glasgow in the early 14th century? It was (and remains) my understanding that no port on the west coast of Britain became particularly important until the “discovery” of, and eventual trade with, the Americas. Looking at an academic paper which gives tables of economic activity in all the British nations, Glasgow is very important regarding the activity of ecclesiastic houses, but the only port on that coast that gets any mention is Ayr; and the tax returns are minuscule compared to the 30% of all Scottish port customs which is from Berwick. Glasgow became a (non-Royal) Burgh in 1214, 90 years after Berwick became King David’s first Royal Burgh. Glasgow itself wasn’t easily navigable till much later. The original port may have been at Newark which became Port Glasgow. But prior to 1668, Newark was a herring fishing village, centred around Newark Castle which was built in 1478 by George Maxwell of Pollok when he inherited the Barony of Finlanstone. So how the film makers justify this eminence, I have no idea. Let us be charitable and say that its a good looking bit of artistic license for Bruce to meet up with Bishop Wishart. It is an irony that the most important port in Scotland is playing the part of a non-entity! *sighs* Where's Wallace?Another old chestnut reflected in The Outlaw King is the story of what happened to the body parts of the quartered William Wallace which leads me to a criticism of the film. This is a really silly thing about the whole saga. Popular tradition says it was Wallace’s left upper quarter displayed at Berwick, probably on the bridge. The film shows the left arm of Wallace on a merket cross (improbably located on the Quayside. So 9/10 for accuracy if the port is Berwick, but it’s -10/10 if it’s meant to be Glasgow: no body part was displayed there. The other quarters were displayed at Newcastle, Stirling and Perth. Finally, let me just reassert for the 94th time that Wallace Green has nothing to do with William Wallace—it’s a corruption of the name given to the area which James Douglas and his men would have, in 1318, been hiding out in—the Walls Green! Anyway, I join everyone’s pleasure in the entertainment (and money) we have been given by the cast and crew and look forward to seeing the film before posting why comments on the “goofs” section of the IMDb! ** Ends ** If this article has sparked your interest and you would like to learn more about Medieval Berwick why not contact Jim who leads entertaining and informative tours (and more) on all aspects of Berwick's fascinating history.

You can follow Jim on Facebook www.facebook.com/berwicktimelines?ref=hl the Berwick Time Lines Blog, and his website https://www.berwicktimelines.com/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy