|

Six years have passed since I last penned a piece about death and its associated records. Although ‘Dispatches’, is as relevant now as it was back in August 2016, there are a few sources and cross-border peculiarities relating to the recording of sudden, suspicious or unnatural deaths and accidents that were not covered at the time. Below are eight of the more unusual departures encountered to date:

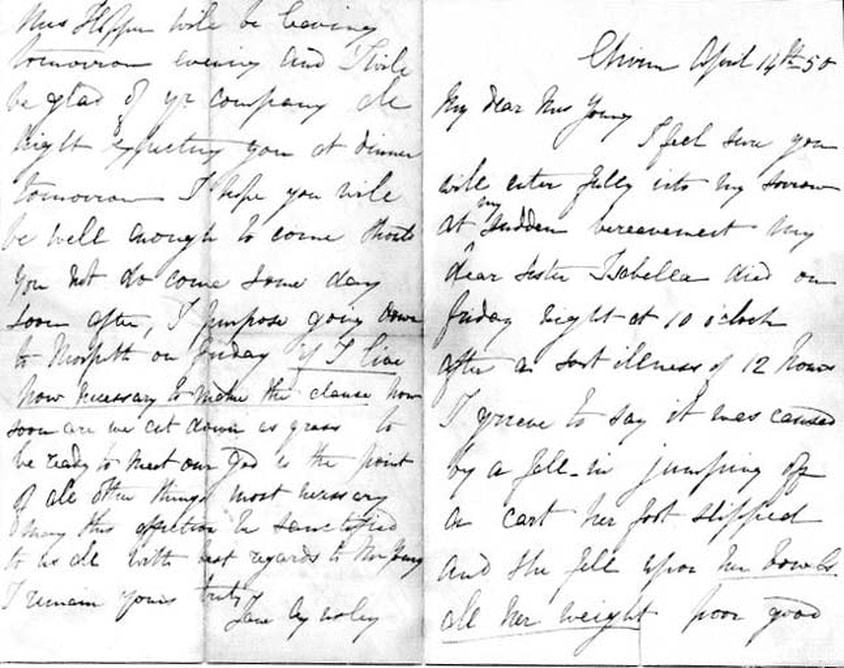

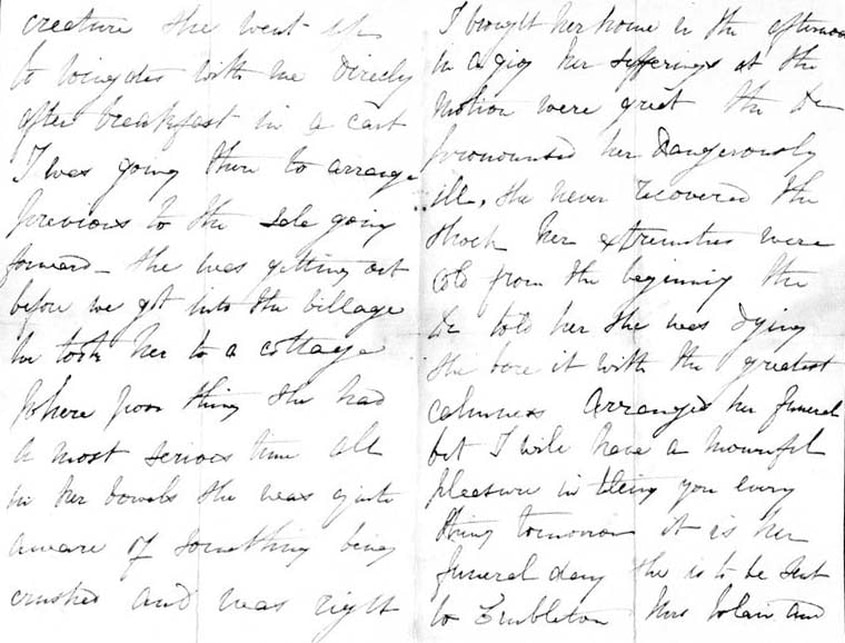

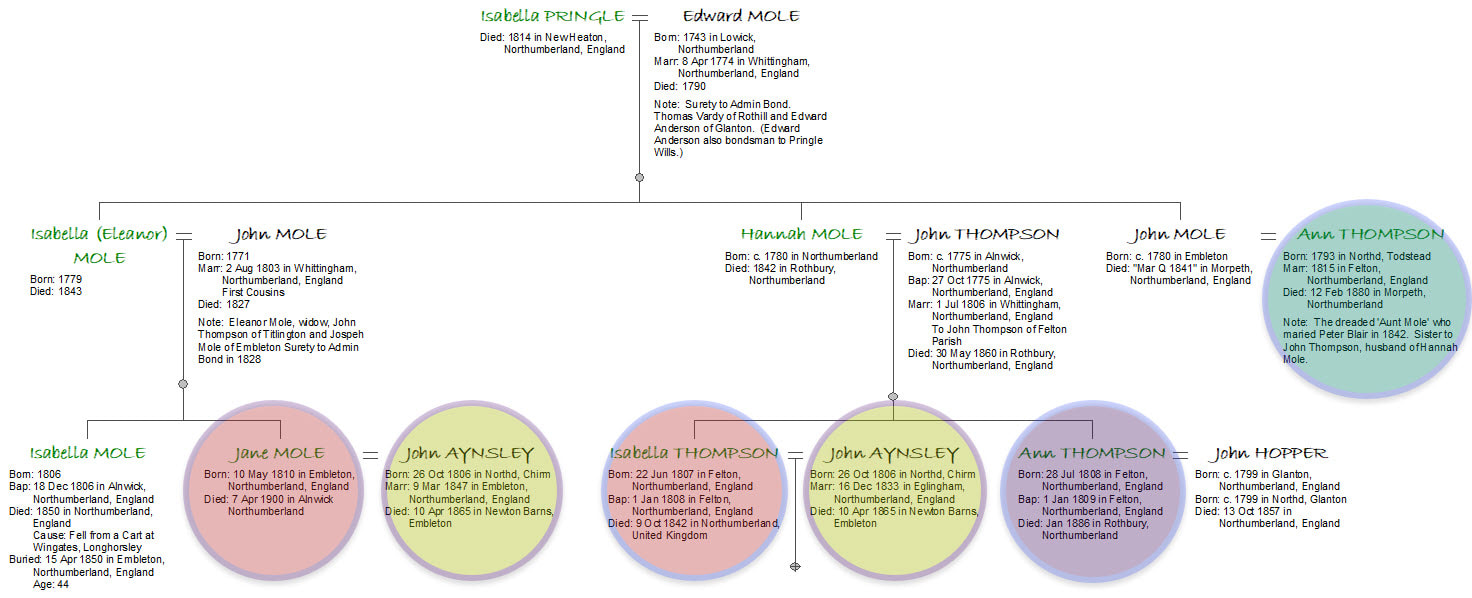

There have been many more encounters with unusual departures since then too. Amongst them, in the collection of family letters, there is the harrowing account of the death of Isabella Mole (A 1C5R to me), who ruptured her bowels in a fall from a cart at Wingates near Longhorsley in 1850. Chirm April 14th [18]50 Jane Aynsley nee Mole (1810 – 1900), was the second wife of John Aynsley, farmer at the Chirm Longhorsley. She is writing to Ann Young nee Whittam, wife of Alexander Young of Swarland East House - a cousin to John Aynsley’s first wife, Isabella Thompson. Isabella was the daughter of John Thompson, the only surviving brother amongst the many ‘Thompson Sisters’ who, in my efforts to trace living descendants, are the subject of my two previous blogs. Isabella Thompson and Jane Mole were both granddaughters of Edward Mole and his wife Isabella Pringle making them first cousins. Other players in the letter are:

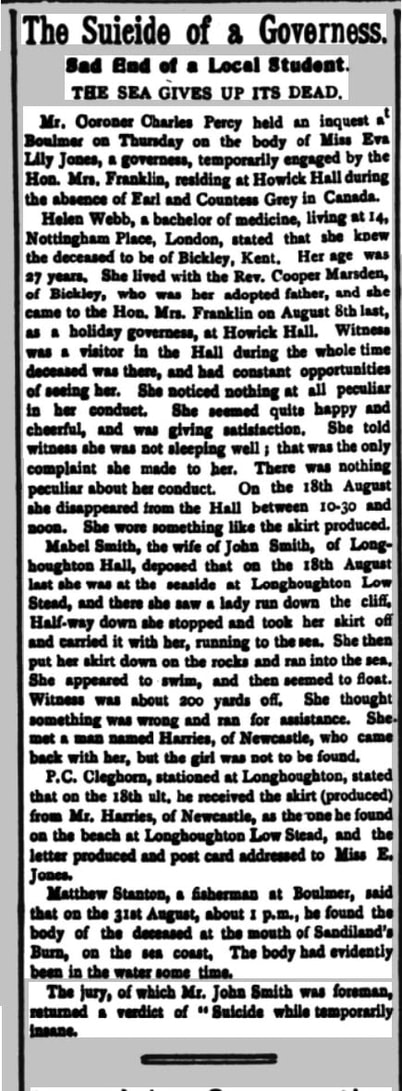

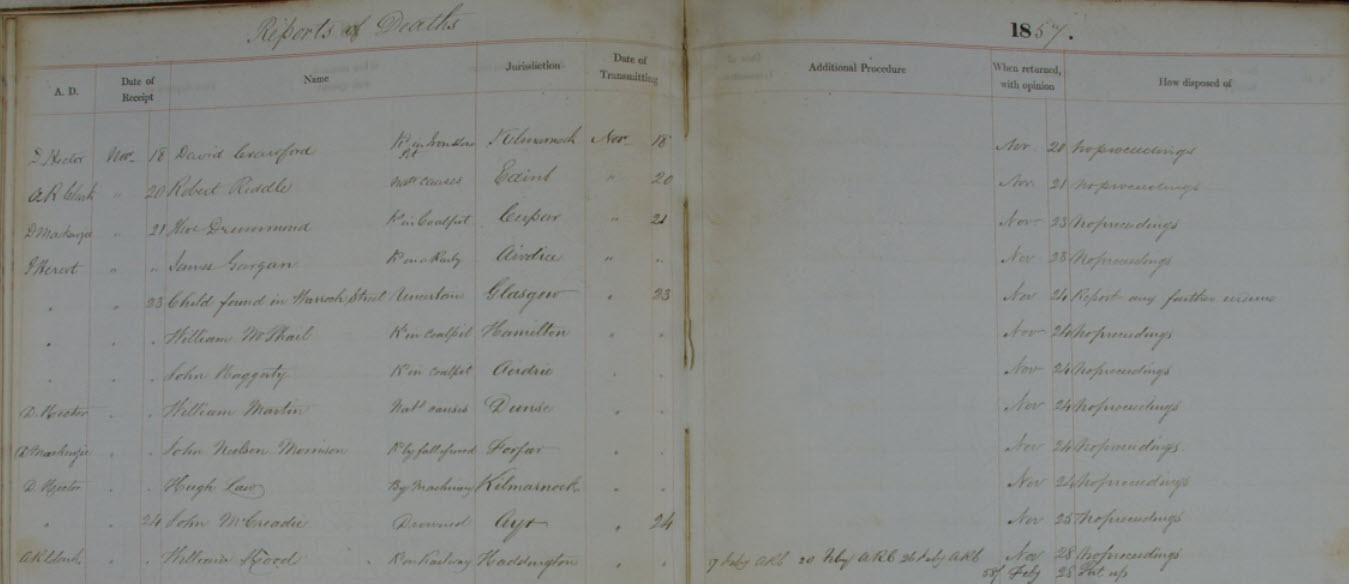

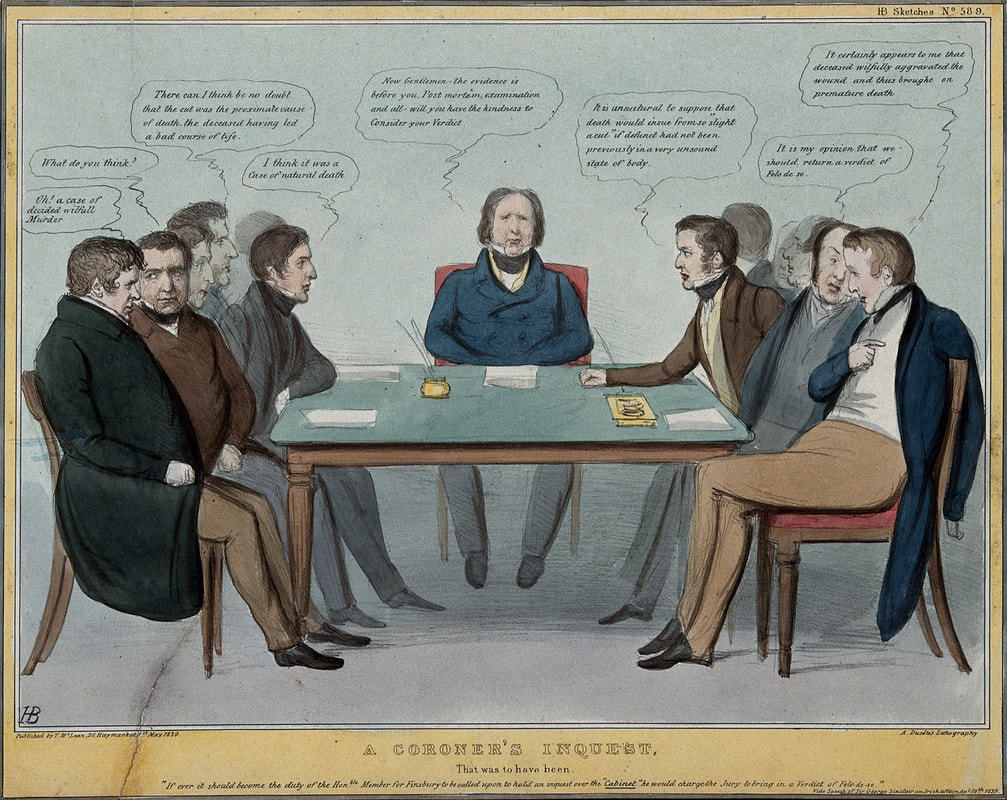

Miss Mole’s demise, like those listed above, was due to accident or ‘misadventure’. In England, deaths in cases of sudden or unexplained death would be referred to the Coroner and if required an inquest held to establish the cause of death. The Coroner The office of Coroner dates from 1194. They are Crown Officials employed to investigate ‘sudden, unnatural or suspicious deaths and the deaths of people detained in prison …’[1] These also include accidents. Coroner’s Inquests, held before a jury up to 1926 were, and still are, public hearings. Historically, venues for inquests were often a local Public House or Inn. Where they have survived, historic records of Coroner Inquests will contain:

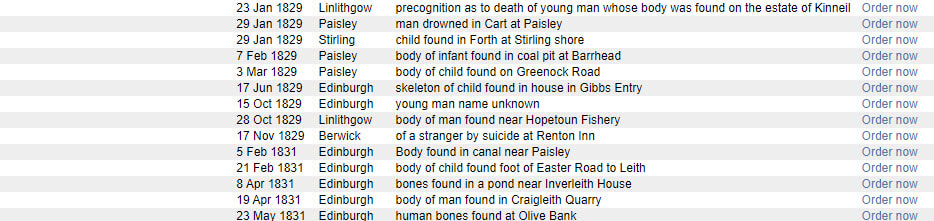

From 1487 until the middle of the eighteenth-century, Coroners presented their inquisitions before the Assizes (or in the case of Berwick upon Tweed, the Quarter Session Court.) If the death was the result of a crime, the coroner’s report served as an Indictment. But even where no crime or trial took place, or in cases of accidental death, the records were filed with relevant court papers. However, the survival of records, especially between 1850 and WW2 are limited and patchy at best. Berwick upon Tweed has a run of early documents held locally under reference BA/J. BA/J/QS relates to the ‘Records of the Berwick upon Tweed Quarter Sessions including Criminal and Civil Jurisdiction’ from circa 1600 and BA/J/CO, covers the ‘Berwick upon Tweed Coroner Court, Inquest Warrants and Coroners Inquisitions’ (1745 – 1942). For records from elsewhere The National Archives holds early records (1228 – 1426) under JUST 2 Coroners' Rolls and Files, with Cognate Documents.

Where an indictment did not result in a trial for murder or manslaughter, the inquisitions were forwarded to the King’s Bench. With exceptions (Chester and Duchy of Lancaster), KB9 holds records from 1485 – 1675 for counties outside of London and KB11 for outside of London from 1675 until the mid-eighteenth century. ‘Whilst some records heard before the King’s Bench survive from 16th century, it is believed that all early records from North Northumberland have been lost.’[4] KB10 contains the records for London and Middlesex.

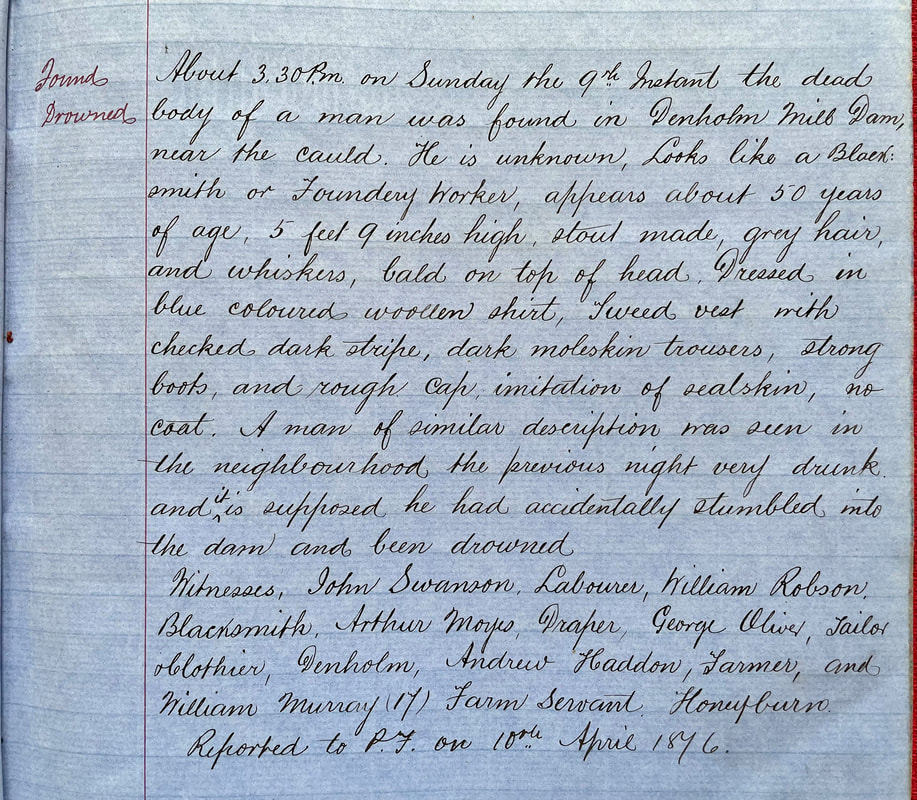

Sudden Death & Accidents in Scotland: |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy