|

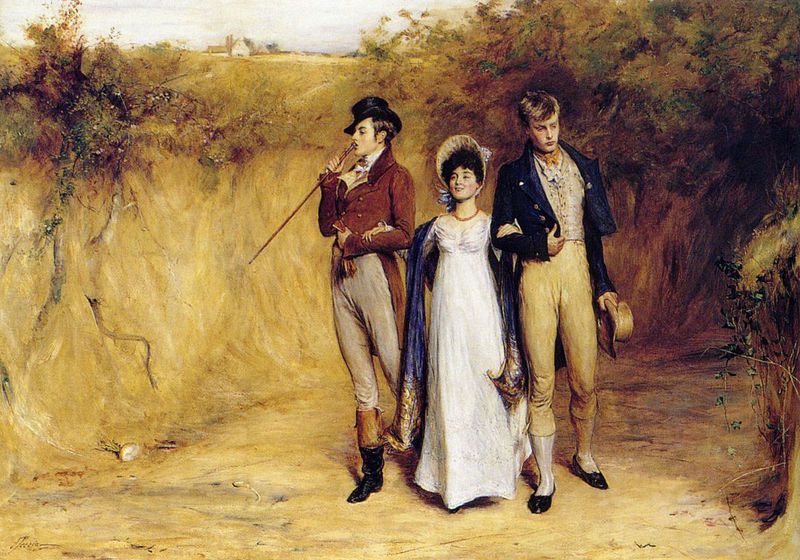

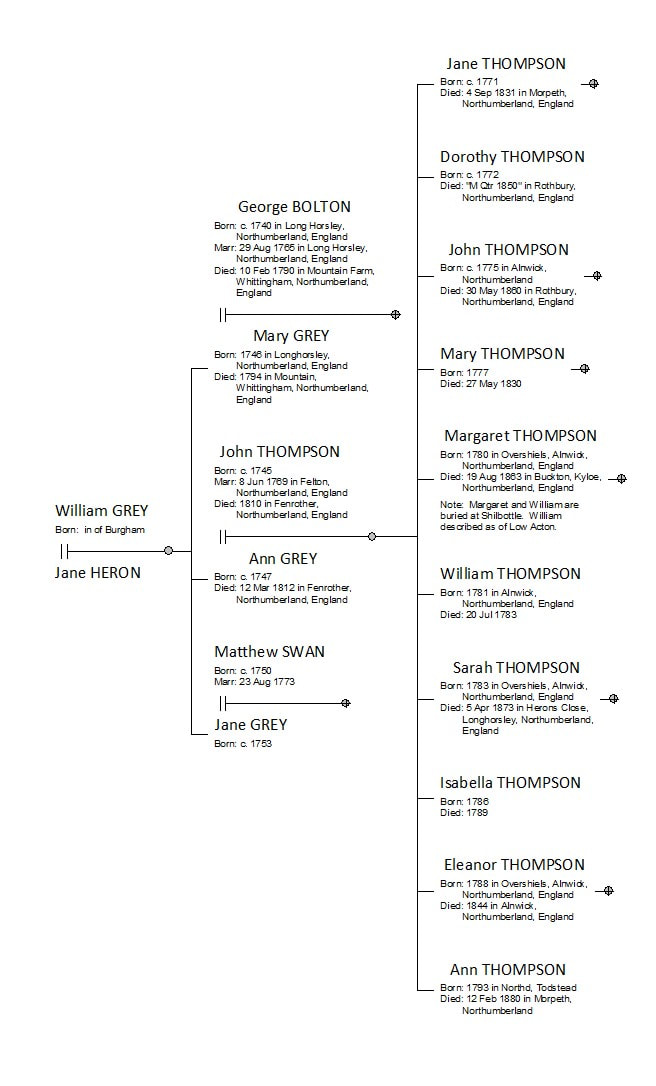

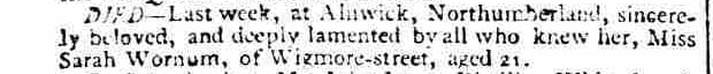

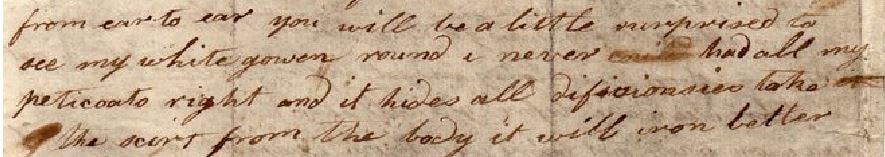

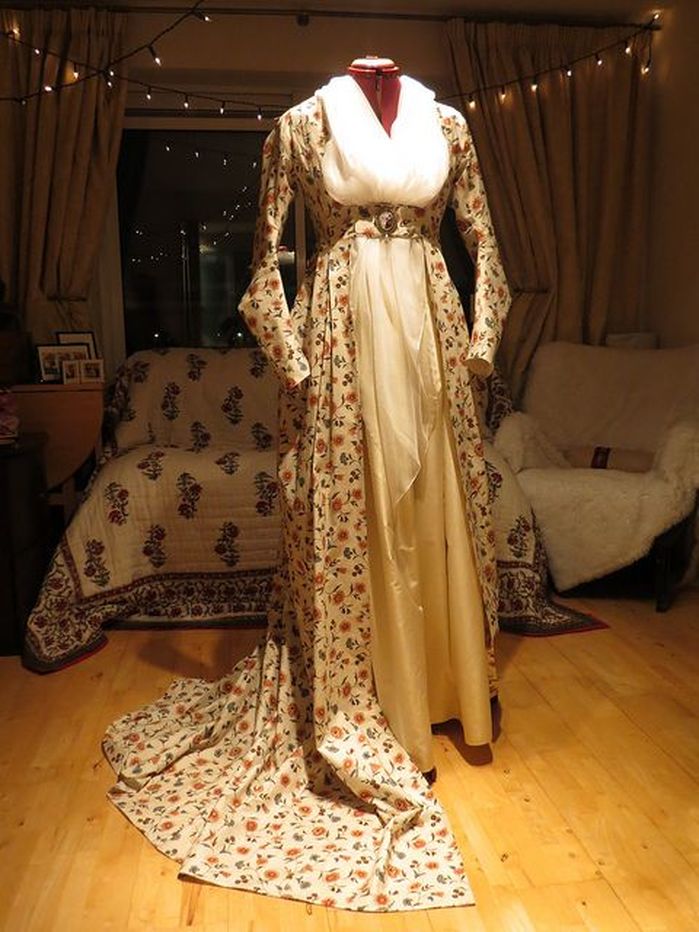

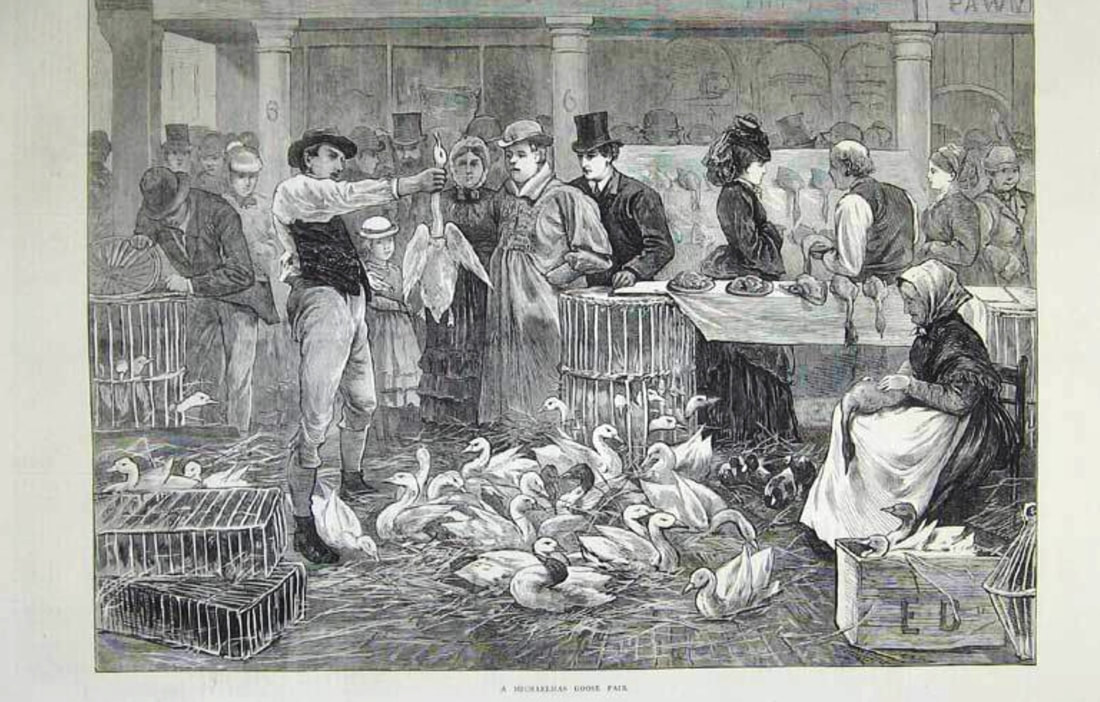

"you often said you would never dow as Dolly had done" Old documents can be very revealing windows into the past. The structure, form and language is as informative as the contents. Nowhere is this truer for the family historian than in personal correspondence, which often on initial inspection seems to talk about ‘nowt nor somat’. The letter that forms the basis of this blog on first inspection appears to be the idle prattlings between two sisters, highly resonant of the Bennet sisters in Pride & Prejudice. However, it does contain snippets of information that reflect the fashions and social customs of the time. The letter forms part of our personal family archive which we are extremely lucky to have and has provided the basis of much research and speculation undertaken by my predecessors. It is perhaps more remarkable in that it is the exchange between two women at a time when basic education of men let alone the fairer sex was often neglected. Forster’s Education Act which gave all children a right to some form of education between the ages of 5 and 13 was not introduced until 1870, some 76 years later. The letter can be accurately dated to sometime before December 1796, possibly that September from the subsequent marriages of some of those persons mentioned within the text. Furthermore, September 30th 1796 was a Friday and as the letter is finished on Saturday at 2 pm it would fit. It is written in a fair italic hand but the spelling is phonetic in places and punctuation none existent. Whilst this is still typical of the period spellings and punctuation were now becoming far more standardised. The form of the letter is therefore possibly the product of a young woman with far more exciting things to do than indulge in meaningful correspondence. So who was the writer? Her name was Mary Thompson, born at Overshiels Farm (Shieldykes) near Alnwick 1777 making her of an age with Jane Austen herself who was born 1775. Mary was the third of seven sisters and one son to survive into adulthood born, to John Thompson of Overshiels and Todstead and his wife Ann Grey. Thus, Mary was one the many grandchildren of William Grey of Burgham and Jane Heron in the maternal line along with descendants of her mother’s sisters the Bolton and Swans. A pedigree that placed her on the edge of ‘county society’ but not necessarily in it. Her letter contains evocative echoes of the youngest of the Bennet sisters, Lydia, with all her talk of fashion, outings and romantic intrigues. Hold this thought as you read on… September 30 Indeed reading between the lines the letters main purpose is to ensure she receives her clean clothes in better time and to impart strict instructions to her sister on the way to iron the skirt of her dress as well as catch up on romantic gossip! I find it quite touching she forgives her sister for not responding as the family are busy with the harvest. Altogether far less glamorous! Unlike Lydia Bennet, Mary appears to be working in an upmarket dressmaking establishment. Where exactly is not known, but an educated guess would be Alnwick. An earlier blog Kissing Cousins under the section of Music and the Mantua identified Nicholson & Wornum (nee Elizabeth Robson) members of other trees in the family coppice from Longhoughton running a Mantua making business in London at a similar time. That connections were being maintained is evidenced in the news paper cutting of 1803 recording the death of her daughter in Alnwick. Furthermore, two further female relatives Harriet Nicholson Stamp and her sister Mary of Alnwick had joined the dressmaking business operating out of Wigmore Street, by the middle of the 19th century. Is it conceivably possible that the ‘Miss Betty’ is in fact Elizabeth Wornum nee Robson? The Georgian era of the 1790’s was a time that witnessed a radical change in women’s fashion as it headed toward the Regency, noted for its elegance and achievements in the fine arts and architecture. Out went the nipped in corseted waists and in came the empire line that flowed freely in an almost elfin Grecian style from below the bust – again think Jane Austen. Perhaps Mary is eluding to her desire to be more on trend when she describes the skirt on her white gown as round, and the apparent aversion to her petticoats. Whether the ‘dificionies’ are with the petticoats or those she perceives with her figure is unknown. The ‘uneform for a lady’ sounds quite intriguing and an altogether more formal affair. I am no expert on either fashion or textiles but have come across this reference to an ‘open robe’ from circa 1795. Mary certainly liked to get out and about and she appears to have had a good deal of freedom to be able to do so. In her letter you can sense her eager anticipation of ‘mickilmiss’. Although it ceased to be marked in the eighteenth century, Michaelmas was a significant date in the agricultural calendar. It marked the end of the harvest, an event which historically would have involved whole communities labouring in the fields in the days before mechanisation. For many farmers it was also the day the rent was payable, and was closely followed by the autumn agricultural ‘Hiring Fairs’. Michaelmas Day was traditionally celebrated on 10th October but when the Gregorian calendar was adopted in 1752 and eleven days dropped from that year, events associated with the end of the harvest were moved by eleven days to 29th September. However, Michaelmas Sunday is still of some importance to Mary. Perhaps her family marked the date with a traditional feast of goose fattened on the corn stubbles? Was this then followed by a blackberry pie? Folklore holds that Michaelmas is the day that Satan was cast out of Heaven by St Michael. He apparently landed in a blackberry bush and being incensed by the thorns he ‘breathed his fiery breath upon the fruit and urinated on them’ – thus blackberries picked after this date will taste sour! However they marked the occasion in 1796 the previous year had been spent at the ‘Weldon Gardens’ the exact location of which I have been unable to conclude in my limited research time. As the farm of Todstead lies adjacent to Weldon, it was presumably in the same vicinity, or possibly at Weldon Hall which stood to the West of what is now the A697. This instalment has, I hope, given you food for thought as to the type of information that can be gleaned from old correspondence, and at least given this letter some historical context. If you take the time to read Mary’s letter out loud, you will perhaps also detect a Northumbrian twang! As to her romantic match making notions, to possibly find out what Dolly did and discover to whom the letter was written pop back at the end of February for the who’s who of the characters mentioned in this little tableau … Useful Links For those of you with a passion for sewing and vintage clothing, or perhaps would like to get going - I thoroughly recommend Cathy Hay's website and blog. http://thepeacockdress.com/ Old Maps are available online at http://www.oldmapsonline.org/ If you would like to learn more about the customs surrounding Michaelmas then this is the blog for you

http://hypnogoria.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/folklore-on-friday-forgotten-feast.html

3 Comments

Ann Humble

28/1/2018 04:58:19 pm

Enchanting !

Reply

29/1/2018 02:57:51 pm

What a super post! Thank you. Looking forward to Part 2. I am in awe of Cathy Hay's skills. Historic costume one of my interests.

Reply

Susie Douglas

30/1/2018 07:44:55 pm

Thank you Rosemary - isn't Cathy clever. I just wish I could sew!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy