|

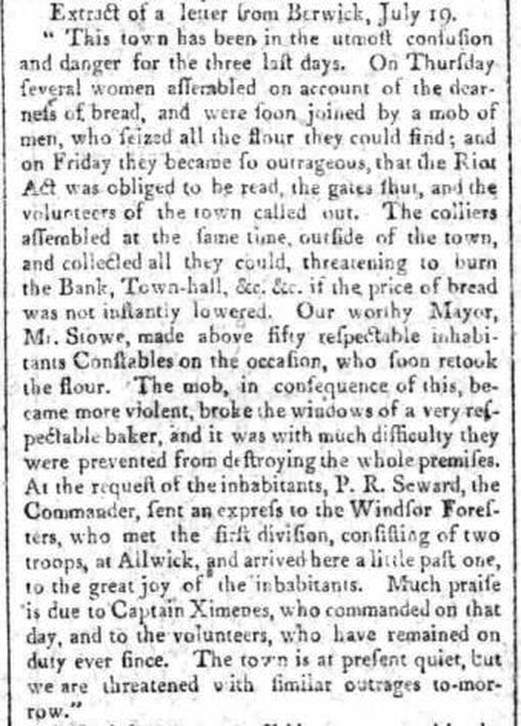

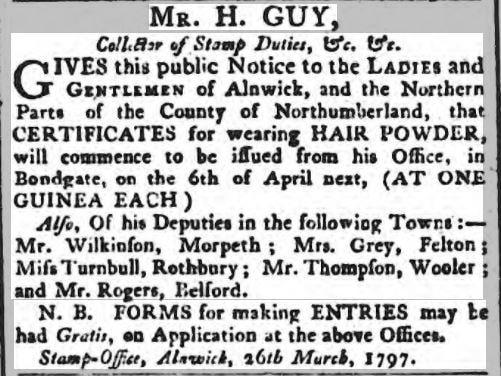

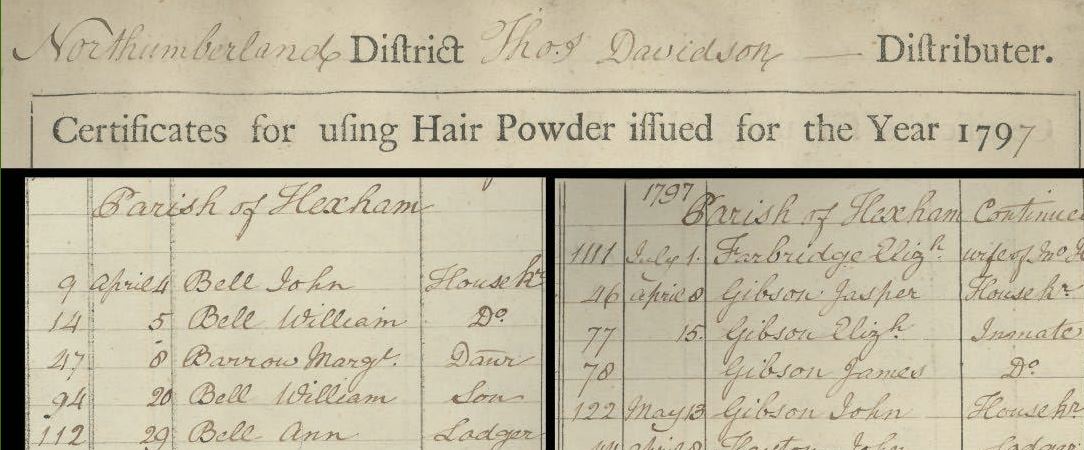

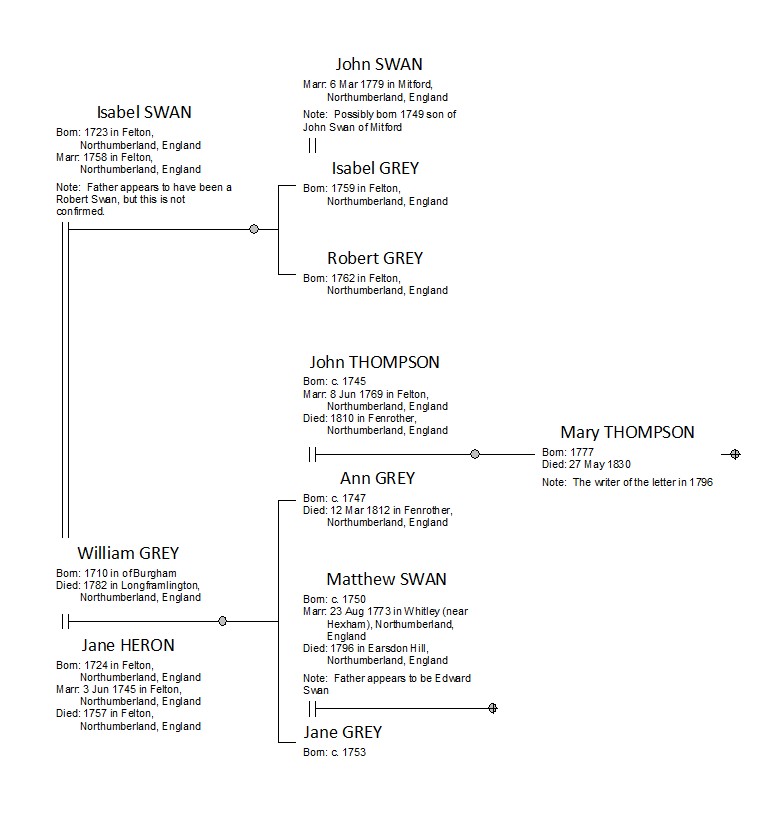

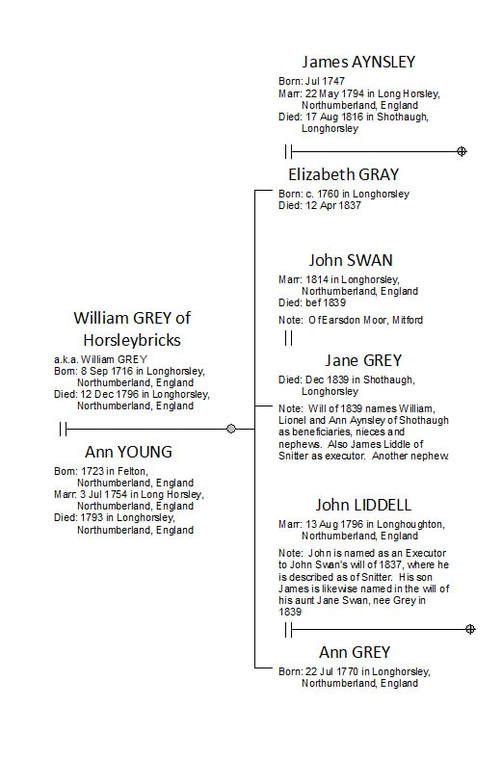

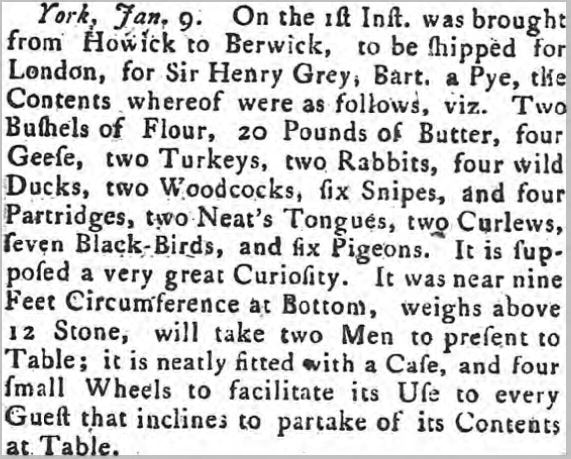

This post is a continuation from last month which looked at a letter written in 1796 between two young unmarried women, sisters Mary and Jane Thompson. The letter sparked speculation as to the meaning behind her comment ‘you often said you would never dow as Dolly had done’. Whilst the context of the statement infers some sort of disappointment in love, this post hopes to add some historical background to the period during which the letter was written. In particular those events involving women. 1796, the year young Mary Thompson put pen to paper, was an interesting year for Britain. It was coming towards the end of the First Coalitionary War with France and in April general Napoleon Bonaparte had begun his campaign in Italy which would result in the eviction of Hapsburg forces from the Italian peninsula. The French Revolution begun in 1789, which some historians state ‘profoundly altered the course of modern history’ marking the decline of absolute monarchies, still raged on. Indeed Britain had lost sovereignty of its colonies in North America in 1783. In August 1796 Spain and France formed an alliance against Great Britain and on 5th October Spain declared war. 1794 to 1796 was also the time of poor domestic harvests, particularly relevant to our band of farming siblings, which when combined with ‘the war against revolutionary France disrupted European trade and the market balance derived from importing grain when necessary was impeded’.[1] Furthermore ‘for 30 years Britain had been on balance an importer of wheat, though on a small scale. Customs duties kept out foreign corn in years of adequate home supplies, but could be suspended when imports were needed’.[2] The harvest of 1794 was one fifth below the national ten year average, with 1795 even worse ‘due to frost and flood’ yielding just 15 bushels per acre ‘when 24 was considered average’. The price of a bushel of wheat rose from an average of circa 6s 4d in 1794 to a peak of 12s 6d in March 1796 which led to nationwide crisis and ‘Bread Riots’. Albeit the west and south of the country were worst affected appeals for emergency supplies were made to the Privy Council by Newcastle and Sunderland in July 1795, the same month a ‘riot’ was led by women and colliers in Berwick upon Tweed. This led to a ‘’Reading of the Riot Act’: The Riot Act[1] (1714) (1 Geo.1 St.2 c.5) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain that authorized local authorities to declare any group of twelve or more people to be unlawfully assembled, and thus have to disperse or face punitive action. The act, whose long title was "An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters", came into force on 1 August 1715. It was repealed for England and Wales by section 10(2) of, and Part III of Schedule 3 to, the Criminal Law Act 1967. It is interesting to note that many of these riots were ‘allegedly’ instigated by women. Author John Hostedt published an informative article on ‘Gender, Household and Community Politics: Women in English Riots 1790 – 1810, for ‘The Past and Present Society’ in 1988 (pp.88 -122)'. In it he argues that the significant roles played by women has been somewhat misinterpreted. On the one hand he refers to the view of historian E P Thompson in 1971, that ‘women were the most involved in face to face marketing, most sensitive to price significancies, [and] most experienced in detecting short weight or inferior quality’. On the other the view of Robert Southey who in 1814 said ‘Women are more disposed to be mutinous; they stand in less fear of the law, partly from ignorance, partly because they presume upon the privilege of their sex, and therefore in all public tumults they are foremost in violence and ferocity’.[3] This difference in these opinions nearly 150 years apart is certainly curious and reflects a marked change in attitude towards the ability of the fairer sex, but like Hostedt I suspect the truth of the matter is something rather more complex altogether. There are further snippets hinting at the financial hardships endured by both the farming and wider community in the post Napoleonic period in another piece of family correspondence dated 1828. It is written from Fireburn Mill near Coldstream by Mary’s youngest sister Anne, (born 1793) by then Mrs John Mole. There will be more on this and 'Aunt Mole' to come in later posts. From her letter in 1796, Mary gives the distinct impression that she is both fashionable and conscious of her physical appearance. In 1797 a rather bizarre tax was introduced by prime minister William Pitt the younger, which, as it applied to many members of society, their families and indeed their servants can be a useful resource for family historians. The ‘Hair Powder Tax’ was effected through the purchasing of a certificate which was then entered in the local Quarter Session court records. It is interesting to note that women were included amongst Mr Guy’s deputies. The information included in the list will provide a date, a parish, a list of names and a description being usually the relationship to the head of the household or another role such as servant. So, like a census return, it is possible to piece together some familial relationships.[4] It is not known if Mary and her family favoured the fashion of powdering their hair or wigs, but a remark on a family tree noting that Mary’s son born after her marriage in 1801 ‘was a dandy’ implies she maintained her sense of fashion and indeed passed it on to her family. The more I read Mary’s letter the more I feel certain at the time of writing she is in the Alnwick area. The biggest clue being ‘… there is a Whail come in at Howick I expect Miss Betty will let me go home with Miss Pallister on saturday to see it and come back on the sunday night’. After a bit of digging I believe Miss Pallister to be a daughter of William Pallister, described at his marriage to Margaret Brown in Howick in 1763 as a ‘yeoman’. The couple had two daughters Margaret b.1775 and Mary b. 1779, one of which appears to have been a particular friend of the letter writer. There is also perhaps the possibility of a distant familial relationship as a John Pallister had married an Anne Swan at Longhorsley in 1792. The Pallister sisters had a brother John who had been baptised at Howick in 1771. With three inter-marriages between the families in the immediate ‘vicinity’ it is a possibility, whilst not confirmed, that cannot be ruled out. The first Swan connection was through the second marriage of Mary Thompson’s grandfather William Grey, who on the death of Jane Heron his first wife in 1757, married Isabel Swan with whom, from evidence in his will, he had at least two children; Isabel b. circa 1759 and Robert b circa 1762. In 1779 Isabel married a John Swan at Mitford. From his first marriage William’s daughter Jane had married a Matthew Swan in 1773. To add to this, but rather more distantly William Grey (Mary’s grandfather) had a cousin (also called William Grey) of Horsley Bricks who, with his wife Ann Young had a daughter they also called Jane. Jane at the time of her death in 1839, was the widow of a John Swan of Earsdon Hill, although from the bequests in their respective wills this union was childless. Instead the primary beneficiaries were John’s Swan siblings, the Aynsley family at Shothaugh and the Liddle family at Snitter, nieces and nephews by marriage. An effort to establish connections between these Swan families has thus far proved inconclusive, but will no doubt unravel in time. Equally, the magic of DNA may come to the rescue, as it has with other descendants in the Thompson and other associated lines. As a note to end this instalment – I did go looking for a mention of a beached whale at Howick in the newspapers. Alas, of the whale there is no mention, but a report in 1770 certainly caught my eye in the form of an enormous pie! There is yet more to come on the various players in this letter tableau as the story of Mary and her six sisters begins to unravel. Remember to drop by next month. References and Links [1] Michael T. Davis, Bread riots, Britain, 1795, The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, Emmanuel Ness (ed) 2009.

[2] Walter M. Stern, The Bread Crisis in Britain, 1795-96 Economica, New Series, Vol. 31, No. 122 (May, 1964), pp.168-187. [3] Robert Southey, Letters from England, ii London 1814 p.47 [4] Sarah Murden, Hair Powder Tax, https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2013/07/22/hair-powder-tax/ 2013

2 Comments

24/2/2018 03:26:28 pm

What a super post! Thanks. I am very taken with the hair powder situation. And LOVE the Stubbs landscape. My - or rather my husband's - Northumberland ancestors all within reach of Hexham would also have been affected by the various wars and other more domestic crises like the price of bread. A fascinating read!

Reply

Liz Powell

9/3/2018 09:59:36 pm

With regard to that enormous Pie; the first Denby Dale Pie was cooked in 1788; a traditio which continues; Google Dency Dale to know more!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSusie Douglas Archives

August 2022

Categories |

Copyright © 2013 Borders Ancestry

Borders Ancestry is registered with the Information Commissioner's Office No ZA226102 https://ico.org.uk. Read our Privacy Policy