By Richard Holt of Holt's Family History ResearchCharities and the Cost of Living:The current cost of living crisis will have many households evaluating their finances. While today’s crisis refers to the cost of everyday essentials rising faster than average incomes, for many of our ancestors the cost of living was a constant struggle. The records of parish charities are often underused by family historians; however, they can provide a wealth of information and contain a fascinating history in their own right. You will see that reference is made throughout this post to a number of under-used sources that can help tell the story of our ancestors in time and place. I hope to piece together some of the more fascinating history of a parish charity and illustrate how this entwines with my ancestors. The ancient parish of Bledlow, Buckinghamshire once included the hamlet of Bledlow Ridge. Bledlow Ridge became a parish in its own right in 1868 when a chapel was built and dedicated to St Paul. My ancestors have a long connection to this parish and it is one of its many charities that is the subject of this post. All but one of the seven charities associated with the parish of Bledlow were created by private individuals. The last charity, stated to be ‘the most valuable of all’ was the outcome of two Acts of Parliament. These Acts were the General Inclosure Act of 1801 and the Bledlow Parish Inclosure Act of 1809. Under the authority of these Acts, the Bledlow Inclosure Award of 14th August 1812 allotted two plots of land in Bledlow Ridge to the Vicar, Churchwardens and Overseers of the parish of Bledlow. It was stated that the land was in substitution for the right of cutting firewood which the poor inhabitants of the parish had previously enjoyed. [1] The charity was thus called the Fuel Charity, but was later known as the Coal Charity when coal, instead of wood, was purchased by the profits raised from the land. This charity was also referred to as the Poor’s Land. The Cost of Fuel:While we are facing increases in the cost of fuel and energy, our ancestors often had a hard time keeping warm in the winter. Found at the back of 'A book of the wills of benefactors and of other writings relating to the parish of Bledlow, 1768’ are charity accounts for the years 1800-1830. In 1813 and 1814, entries for ‘tickets for wood’ and ‘tickets for scrub-wood’ appear. These tickets were issued by the Vicar to the individuals named in the accounts. [2] This firewood was grown on one of the plots of land allotted by the Bledlow Award of 1812. This plot of land was situated at the top of Loxborough Hill fronting the north-east side of the road. A number of entries in the charity accounts give more information about the management of the land and the beneficiaries of the firewood. The wood was cut between November and January of each year depending on its growth. In 1818 the following entry was made: "About the beginning of November 1818, a portion of the Scrub Wood on Loxborough Hill was begun to be cut for the use of the poor it having attained in the opinion of the Trustees a sufficient growth since the last cutting (Christmas 1814). Men were employed in cutting under the direction of Mr. Gibbons the Churchwarden at 10d per score of faggots which were served to those poor persons who produced a ticket from the Vicar empowering them to receive on paying for the cutting. Three score of faggots was allowed to each. Five kept or contributed to by persons entitled to the wood. The number of claimants was found to be great not less than a hundred. About half the ground or 13 acres was cut this year." It seemed that there was a growing need for firewood by the poor of the parish and in 1819 ‘only a small portion of the wood [was] left standing for another year’. It was said that ‘the number of claimants [was] greatly increasing’ and a list of individuals issued with tickets amounted to 86 families in Bledlow and 46 families at Bledlow Ridge. It seems that the Scrub Wood was struggling to revive itself after each cut and in 1820 the Fuel Charity turned to purchasing coal. This was bought, in part, out of the rent from five cottages on the second of the two plots of land allotted by the Bledlow Award known as ‘The Scrubbs’. [3] In 1820, around 140 families were each supplied with around 100kg of coal. This amounted to seven wagon loads which were provided by Lord Carrington and a number of the local farmers. Five of the wagons were stationed at Bledlow and two at Bledlow Ridge, where the coal was weighed out and distributed. It is not until 1822 when we next hear about the Scrub Wood at Loxborough Hill. In this season, the wood was “cut throughout the whole piece clean to the stumps the faggots being small & the wood only of three years growth and the number of claimants very large about 150 families who were supplied with 60 faggots each on paying each eight pence per score for the cutting.” It seems that there were growing issues with how beneficial the land was seen to be. The Vicar, William Stephen, explained that the wood was “considered as very unprofitable, to those who live at a distance especially, and a wish [had] been expressed by many of the poor that the land could be grubbed & let for tillage - but this is contrary to the express words of the Act & could not be accomplished without general consent.” [4] It would appear, that by Christmas 1825-1826, the use of the land on Loxborough Hill had changed. The accounts explain that “the Poor’s Land at Loxborough Scrubbs having been completely grubbed in the winter of 1824-1825 was let in two equal portions of 12 1/2 acres each for cultivation on a lease of twenty one years at 11s/- an acre to Mr. Philip Gibbons & Mr. Thomas Chown. The rent to be laid out in fuel.” [5] This is confirmed by the entry for Christmas 1826-1827 when it was “resolved to purchase coals [with the rent from the two plots of land] in preference to any other fuel.” Ten tons of coal were brought from Wendover Wharf on the 20th December 1826 and distributed the next day. The coal was issued by tickets that were given the poor who were deemed entitled. The parish purchased a further two wagons full of coal for the poor who were able and willing to pay the wharf price and distributed it to those who had purchased tickets. It is needless to say, that despite receiving aid from the charity, our ancestors had to pay a high price to keep warm during the winter. Living Conditions, Housing and Rent:The plot of land known as ‘The Scrubbs’ provided income for the Fuel Charity from the rent of five cottages known as Colony Cottages. These cottages had long been connected with my ancestors, the Brooks family, as well as being entangled in local disputes, lore and legends. The Brooks were once referred to as “nomadic people… [who] squatted on… land called The Scrubbs.” [6] Today the track down to the site of Colony Cottages is called Scrubbs Lane. It was rumoured “that the houses in Scrubbs Lane (Colony Cottages) passed to the person who had his or her shoes in the fireside on the death of the owner.” [7] The Bledlow Award map “indicates that there were two small structures on the plot of land at the time of the Inclosure although no mention of them is made in the award itself.” It seems that the Charity Commissioners referred to "four cottages let at 16/- each” although five cottages are mentioned in many other sources. [8] These cottages became a constant source of trouble for the charity. Writing about the Bledlow Charities in 1936, McGown stated the following: “When these cottages were built and by whom is not definitely known. Their ownership seems to always have been a matter of dispute between the trustees and the occupants.” [9] The first reference to “the Brooks’ Cottages” is found on 30th January 1820 when “the Rent of 5 Cottages & Gardens occupied severally by Richard, William, Ambrose & Francis Brooks & Henry Newell” was recorded. The entry states that the cottages were “on land allotted to the Officers and Trustees of the Poor. The rent [was] 16s a year each & [was to be] paid half yearly.” This year the rent money was added to the Coat Charity set up by Henry Smith’s will of 1627 “in consideration of £4 of Smith’s Charity being employed towards apprenticing a boy.” [10] Richard Brooks, William Brooks and Francis Brooks of Colony Cottages, Bledlow Ridge are all my direct ancestors. In fact, Richard and William Brooks feature more than once in my family tree on both my paternal and maternal lines. In 1915, John William Turner, Headmaster of Bledlow Ridge School, even had a favourite joke: Why is Bledlow Ridge School like a river? Because so many little Brooks run into it. [11] The same could be said about my ancestry! It appears that the occupants of Colony Cottages struggled to pay their rent. The Rev. William Stephen added 4 shillings to the rent collected during the period from 21st December 1830 to 7th March 1831. In 1832, Ambrose Brooks had fallen in arrears and paid £1, 4 shillings ‘in part for three years’ rent and the Vicar excused him for the year he advanced his rent. It is also recorded that “Richard Brooks had not paid [his rent] up to March 7th & probably will not pay his rent to Mich[aelma]s 1831.” In 1833, Richard paid 10 shillings towards 2 years worth of rent; and while he paid his rent of 16 shilling in 1834, he was still in arrears of £1, 2 shillings. The entry for 1835 reads “R. Brooks in debt £1..18” and records no payments against his name. In 1836 Richard Brooks paid £1, 1 shilling towards his rent arrears and Ambrose Brooks was also paying arrears. The following note at the bottom of the entry reads: “N.B. R. Brooks left 17d Arrear & 16/1 Michs. Rent hitherto unpaid. But his cottage is ready to fall & hardly worth any rent. But he promises payment. A Notice has been served on all these cottagers to admit no more Inmates. Willm. Stephens.” Clearly the cost of living was a crisis that these families could not avoid. The Brooks brothers had fallen into a cycle of rent arrears; their arrears increasing despite payments towards the rent owed. We also learn that the condition of the housing was very poor, with at least one of the cottages nearly falling down. It is no wonder that the surname Brooks appears multiple times in the petty session records for trespass charges in pursuit of conies and game. Poaching was one way of feeding their families. It is not hard to image that the fight for survival was a constant struggle. On 3rd January 1837, one of the major landowners, Henry Gibbons, paid the yearly rent of 16 shillings on behalf of Richard Brooks. Another lifeline was passed to Richard Brooks as the Rev. William Stephen excused all arrears. Gibbons also paid Richard Brooks’ yearly rent on 21st December 1837. Despite such benevolence, Richard was unable to pay his rent in 1839 and Henry Gibbons, having stepped up two years in a row, declined to be answerable for the rent. Still a year later in 1840, Brooks settles his rent arrears while Henry Gibbons furnishes him with the 16 shillings for the annual rent. At this point, Richard was 75 years of age and probably in poor health. [12] Colony Cottages - Ownership Dispute:It seems that Gibbons had accepted this custom of paying 16 shilling for Richard Brooks’ rent as the same occurred in 1841. It is interesting to note that the 1841 account book entry reads as follows: “Rent of Cottages, Gardens etc. (or quit-Rents on grounds).” Richard Brooks died the following year and was buried at Bledlow on 16th February 1842 at the age of 77 years. Even though his life may have been somewhat ‘nomadic’ with it being claimed that he ‘squatted’ on The Scrubbs, his legacy of survival lives on through his many living descendants. In 1841, the Rev. William Stephen penned his ‘observations’ in relation to the charities. Regarding “the Rent of the Brooks Cottages,” he said that “the Charity Rents should… be paid in Public Vestry & proper Receipts given.” No further mention of the rent payments appear in the charity accounts from 1841-1854. The historical record does not turn silent despite the cottages not appearing in the account books for these dates. Even for cottages which were about to fall down and ‘hardly worth any rent’, they are the subject of much dispute and controversy. Jumping forward in time to September 1896, the following letter was published in the Bucks Free Press: OVER-CROWDING AT BLEDLOW RIDGE In 1911 the Bucks Herald reported on a case heard at the High Wycombe County Court on 6th April. The case was reported as follows: A BLEDLOW RIDGE CASE Mrs Brooks was the widow of Jesse Brooks whose obituary appeared in the Bucks Free Press on 21st May 1909: OBITUARY - We have this week to record the death of an old and well-known inhabitant of this village, Mr. Jesse Brooks, of “The Scrubbs,” which took place on Wednesday, at his residence, at the age of 76 years. Deceased, who had been in failing health for several years, was a well-known figure both in this and surrounding villages, through his lifelong occupation and frequent attendances in different localities as chimney sweep, an occupation which he followed with credit and success as long as health permitted. He was much respected by all who knew him. Deceased had been married twice, and leaves a widow, two sons and four daughters to mourn their loss. We understand that the funeral will take place at Bledlow Ridge Church on Saturday, at 4 p.m. When the Valuation Office conducted its survey of Bledlow Ridge in accordance with the Finance Act of 1910, the dispute over ownership of the cottages was raised. Ordinance Survey maps were annotated by the surveyors and assessment numbers were recorded for each property. These assessment numbers are referred to in the field books which contain various information about the properties as recorded during the survey. The image below shows the field book for Bledlow which contains the information on ‘Scrubbs Cottages’. The field book contains a sketch plan of the properties and numbers them consecutively from 282 to 286. [15] The occupants of each of the properties are shown as follows: 282 - Thomas Smith 283 - Mrs Brooks 284 - Newell 285 - Isaac Brooks 286 - James Brooks The inspections were made on 2nd October 1913 and the annual rent of each of the cottages is shown to be 15 shillings. The rent for cottage #283, occupied by Mrs Brooks, has been changed to 25s. with a note in brackets reading: “Now the Vicar claims 25/-” Clearly there was still some issue with the rent for this particular cottage following the court case two years previously. There is further evidence of this in McGown’s writings where he states the following: “The Trustees Minute Book records that in 1913 as a result of successful litigation against one of the tenants the future terms of the cottages were settled between the trustees and the tenants as follows:- the tenancies to be yearly at rents of 25/- each, tenants do repairs and pay rates.” [16] While McGown applies the rent of 25s. to all the cottages, only Mrs Brooks’ cottage is subject to the amended rate in the field book. Furthermore, McGown states that “in spite of this settlement, the tenants continued to regard themselves as the owners of their respective cottages and claimed that the rents of 25/- were ground rents only.” The field book also adds further descriptions of the properties, referring to #286 as a “2 Roomed apology for a cottage.” A note under #282 reads: “N.B. The tenants of all these 5 cottages maintain that the Buildings are their own & that only the land belongs to the Charity. The Building[s] are in the most cases homemade affairs & very often been erected by the present tenants.” From what we have learned of Colony Cottages, it is easy to build a picture about how they may have looked. I refer back to the note in the charity account book from 1841 which read: “Rent of Cottages, Gardens etc. (or quit-Rents on grounds).” This would seem to support the occupants’ claims that the houses were their own and erected by themselves. Having seen that the cottages were ‘homemade affairs’ and an ‘apology for a cottage’ it is not difficult to imaging how the Brooks’ and other occupants may have lived. The many Bledlow charities had been consolidated on 15th October 1909 to be run under the title of the Consolidated Charities. [17] There were further disputes in 1931 and much was done at this time to ensure the charities were administered correctly. An article in the Bucks Free Press dated 6th February 1931 discussed the ‘Bledlow Charities Dispute’ with the following in bold: “ALLEGATIONS that the trustees had wrongfully distributed the Bledlow Charities, and that one trustee had taken possession of a cottage at a rent of 25s. a year, were made at a Parish Meeting at Bledlow Ridge on Monday.” [18] It was claimed that “one of the trustees of the Parish Council had moved into occupation of the Scrub Cottages at the old rent of 25s. a year.” The article noted that the Charity Commissioners wrote to the Parish Council stating “that Scrub Cottages belonged to the Charity and if one became vacated, it should be publicly advertised by the Trustees.” There was much debate at the meeting relating to the custom of giving gifts and various people believing they were entitled to such charitable gifts on the basis that they had always received them. The parishioners wanted to know if the Charities were run properly. The chairman explained that the trustees had ‘rather wide powers’ and that a good deal was left to their discretion. Mr J. Keen asked: “Can you explain the Consolidation Act then?” The chairman responded: “You would need a lawyer to do that. It would take him a couple of hours and then you would hardly be able to understand it." The article continued: “Major McGown said that he was sincerely sorry that tenants in several of the cottages which belonged to the trust, and which the tenants looked upon as their own, now found that they had no right to the cottages. Perhaps something could be done on their behalf. They might be able to negotiate with the Charity Commissioners to get a 21 years’ lease upon the cottages.” A voice responded: “Twenty-one years? I have lived in my cottage all my life as my father and grandfather did before me. I don’t want 21 years’ lease but 60 years.” In the next issue of the Bucks Free Press, dated 13th February 1931, the following letter appeared: Here, William Robert Keen of The Scrubbs, Bledlow Ridge explains that the cottages belonged to the people who lived in them subject to a quit rent charge of 15s. per annum and not 25s. as stated in the article. It seems that the 25s. may have only applied to Mrs Brooks’ cottage as noted in the field book. The claim that the properties were owned by the occupants who paid ground rents only led to one of the properties changing hands in 1930 on this basis; “the new occupant purchasing possession from the representative of the deceased occupant.” [19] Interestingly, the debate of property ownership came to an end in 1931 in a move to avoid the expense required in litigation to assert the Trustees right of ownership relating to the property sale the previous year. The charity Trustees came to an arrangement with the tenants “for the sale of the cottages to their respective occupants on special terms. The Charity Commissioners consented to the sale on the condition that the full value of the entire property, as assessed by an independent valuer, was paid to the Charity account. Each tenant paid as much of the purchase money as represented the value of the plot of ground in which his cottage stood and the Trustees found the balance of the purchase money from outside sources. The proceeds of the sale were invested in War Stock producing a yearly income of £9 15s. as against the previous rental of £6. 5s. The occupants of the properties thus became the legal owners in freehold of their respective cottages and garden plots, and the long-standing dispute between them and the trustees was brought to an end.” [21] Sadly, with the cottages being in a dilapidated state, in 1935 the Public Health Committee recommended that the Council make Demolition Orders in respect of the following: No. 2, Scrubbs Cottages, Bledlow Ridge, A. C. Stallwood No. 3 Scrubbs Cottages, Bledlow Ridge, Mr G. A. Smith No. 4 Scrubbs Cottages, Bledlow Ridge, Mr Owen East [22] That same year, it would appear that the Council proposed the site at Bledlow Ridge for a housing scheme. “The District Valuer’s report stated that the cost of acquiring the freehold of No. 4, The Scrubbs, Bledlow Ridge, with the right of way and vacant possession would be fairly represented by the sum of £30, and it was resolved that this offer be made to the owner and that the consent of the Minister of Health be applied for.” [23] Whatever the eventual fate of the cottages, they are enshrined in history and a story that deserves more attention than is given here. When we put the lives of some of our ancestors in context, it helps bring a new perspective to the modern day. Note: The Consolidated Charities still exist today under the name Bledlow Charities; Charity Number: 203785. Footnotes:[1] McGown, Melville, The Charities of the Ancient Parish of Bledlow in Buckinghamshire, Freer & Hayter Printers, High Wycombe, 1936, pp. 6-7. Lipscomb, George, The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham, Vol. I, London, J. & W. Robins, 1847, p.123.

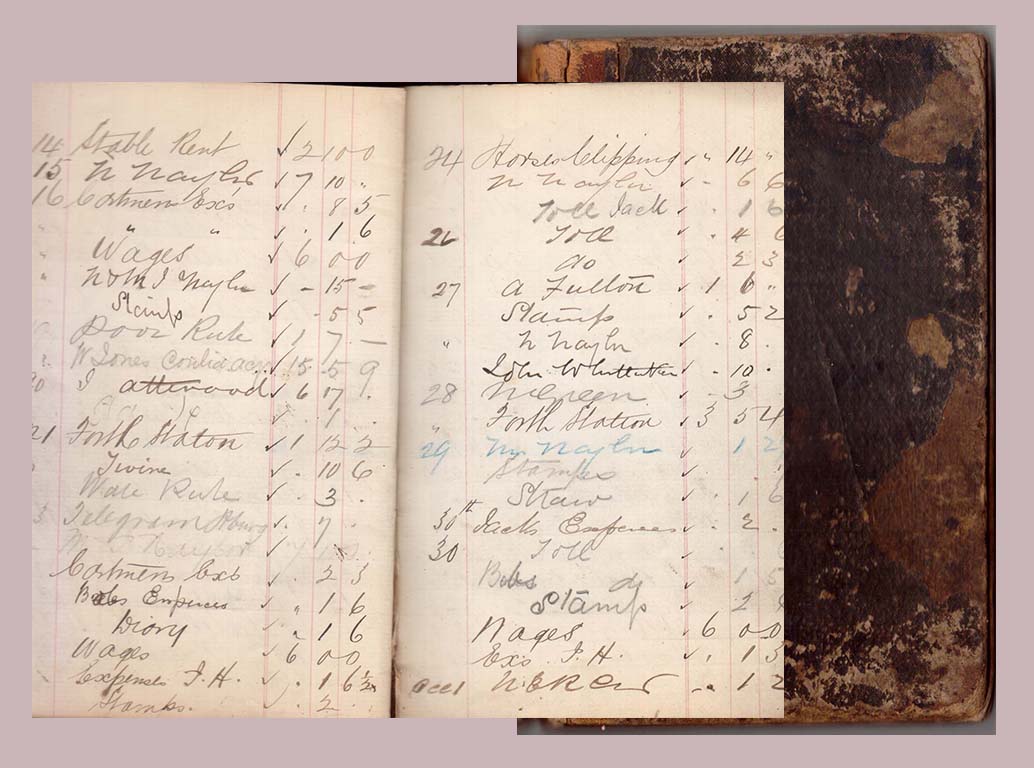

[2] Bleldow Parish Records; Charity and Schools [Bledlow], ‘A book of the wills of benefactors and of other writings relating to the parish of Bledlow, 1768', 1768, 1800-1831, PR_17/25/2, Buckinghamshire Archives. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] The Buckinghamshire Village Book, Buckinghamshire Federation of Women’s Institutes, Countryside Books, 1987, p.19. [7] Oakley, Gwen, Bledlow Ridge, 1973. [8] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14; Public Charities, Analytical Digest of the Commissioners’ Reports, In Continuation of Digest Printed in 1832, London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1835, p.16. [9] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14. [10] 'Charity book' [accounts of payments to the poor] [Bledlow], 1702-1759, 1830-1853, PR_17/25/1, Buckinghamshire Archives. [11] Bledlow Ridge Board School in 1915, Photograph and Article, Newspaper Cutting in possession of author. [12] 'Charity book' [accounts of payments to the poor] [Bledlow], 1702-1759, 1830-1853, PR_17/25/1, Buckinghamshire Archives. [13] Over-Crowding at Bledlow Ridge, Typed copy of article from Bucks Free Press, September 1896, email from Mary Anne Britnell, 17th September 2000, copy in possession of author. [14] A BLEDLOW RIDGE CASE, The Bucks Herald, 15th April 1911, p. 3, col. 2-3 [15] Board of Inland Revenue: Valuation Office: Field Books, Bledlow Assessment No. 201-200, IR 58/39387, No. 282, The National Archives [16] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14. [17] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.10. [18] Bledlow Charities Dispute, Vicar’s Action Defended at Parish Meeting, Bucks Free Press, 6th February 1931. [19] McGown, Melville, op. cit., p.14. [20] "Former miller, Bledlow Ridge, Bucks - Mr Keen?”, VENN-IMG-01-023, The Mills Archive, available at: https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/former-miller-bledlow-ridge-bucks-mr-keen, accessed: 22nd August 2022. [21] McGown, Melville, op. cit., pp.14-15. [22] Demolition Orders, Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News, Princes Risborough “Advertiser”, 6th September 1935, p.2, col. 3. [23] HOUSING SITES, The Bucks Herald, 6th September 1935, p.15, col. 5.

0 Comments

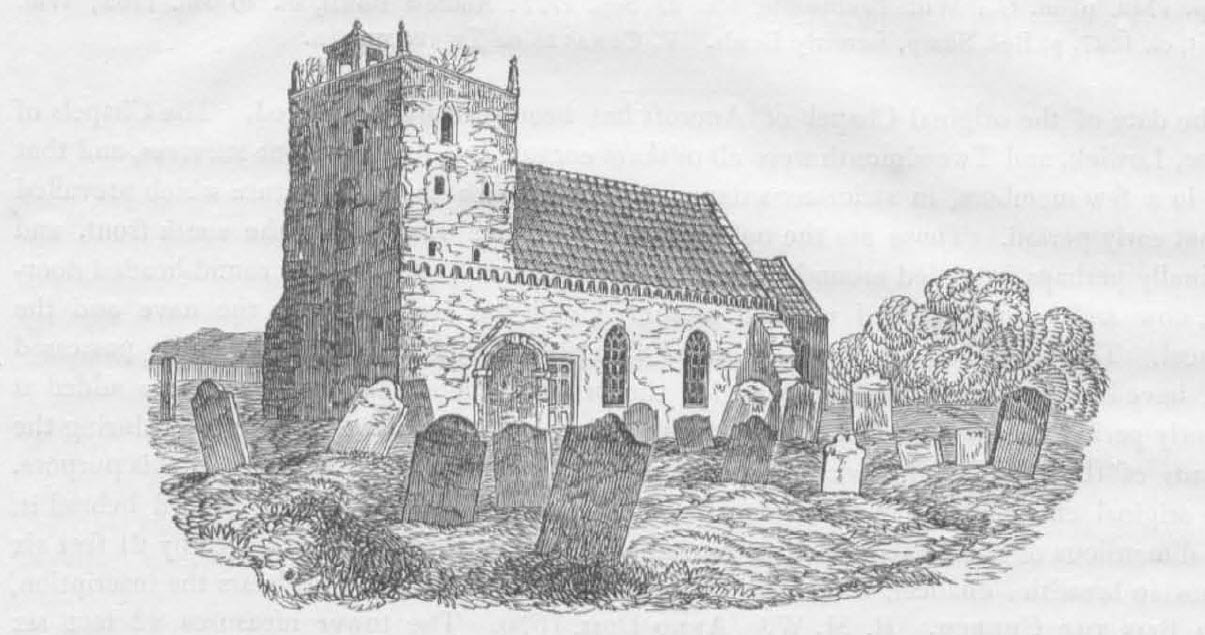

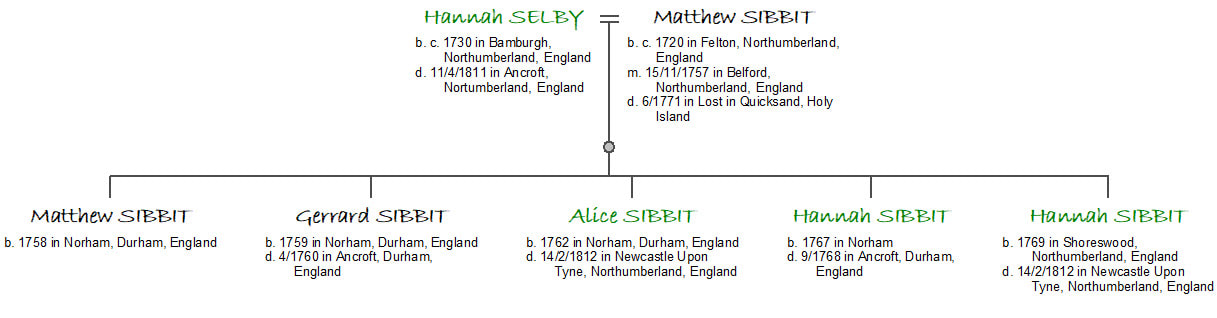

Part 1. BackgroundHidden behind a large, padlocked oak door in Ancroft Church is a burial vault containing six lead-lined coffins. It is small with a low vaulted brick ceiling and stone walls. Even with the door open a torch is required to penetrate the intense darkness to reveal the three coffins lying shoulder to shoulder, three to either side. To the left, the heads of the coffins rest in niches cut into the walls, to the right, the stone niches support the feet. The coffins are so close together it is impossible for a person to pass between them or to see what supports them underneath. The original wood of the outer coffins is largely gone, rotted away with time in pitch-black silence and with it any visible means of identifying the occupants if indeed they ever existed. If the supports are also made of wood and as rotten as the coffin casings, there is an overwhelming sense that the slightest knock could send their cargo crashing to the floor at any moment. A scattering of debris and sections from the collapsed wooden sides litter the floor and a couple of scraps of what may once have been a mortcloth remain on the surface of the coffin nearest to the door. So, who are the six individuals sleeping in this cramped space and how long have they lain in what is essentially an above-ground crypt? The church records do not distinguish between burials in the churchyard and the vault and there is no sign of any surviving breastplates that might hold a name, a date or other clue to help identify the occupants. Strange perhaps given a lead-lined coffin would have been a considerable expense. … The engraved breastplate was the most important item and usually the first to be added if a coffin had any fittings at all. [1] But then, if the vault and its occupants all ‘belonged’ to a single family would name plates be required at all? I confess I knew nothing about the burial vault at Ancroft until I was contacted in March last year by local historian Julie Gibbs asking if I was connected to the Sibbit family of Ancroft Greenses. The answer was yes, descendants and relatives of the Smiths of Horncliffe Loanend attached themselves to members of the Sibbit family by marriage not once, or even twice but three times in the same generation! Brothers Robert and James White Smith sons of George Smith of Ancroft, (eldest son of George Smith of Horncliffe Loanend and his wife Christian Trotter), both married daughters of John Sibbit of Greenses House. Robert married Mary Ellen Sibbit a daughter by John’s first wife Catherine Sutherland in 1882 and James married Catherine Sibbit a daughter by his second wife Mary Anne Smith in Edinburgh in 1885. The third family member to marry a Sibbit was a Trotter second cousin, Esther Hislop, who married Adam Sibbit Junior, a medical doctor, at Prestonkirk in 1886. Needless to say, there are more interesting connections too. As a result, George Aynsley Smith did a bit of research into the family and traced the Sibbit family tree back to the mid-eighteenth century. A great foundation to build upon and from some further investigation intriguing stories are coming to light to attach the pedigree framework. But what has this to do with the burial vault? Julie was specifically searching for descendants of Adam Sibbit Esq of Greenses House. In 1810 the Bishop of Durham granted Adam Sibbit the faculty of a burial-ground or vault, within the north side of the tower on the west end of the Chapel; length from north to south eight feet three inches; east to west twelve feet two inches, inside measure.[2] His wife Isabella Yellowly, who died the following year, was likely the first to be placed in the vault and Adam himself joined her in 1812. But so many questions remain; who WAS Adam Sibbit, what was his family’s connection with Ancroft and not least who are the other four individuals in the vault? Included at the end of this instalment are links to some useful sources used along the way. Ancroft Church and links with the Sibbit FamilyIn 1828, Parson and White describe the church at Ancroft as … an ancient edifice covered with red tiles and having a large ash tree growing in the middle of its decaying tower. Though it was anciently a chapel to the curacy of Holy Island it now enjoys the privileges of a distinct parish. And Raine’s ‘The History and Antiquities of North Durham’ contains a more detailed description of the tower. … In one of the stories [sic] is a fireplace, and the lintel of one of the doorways is formed of the lid of a stone coffin disturbed for the purpose, upon which there is a rude carving of a sword. The floors of these upper rooms, which were of wood, fell long ago, and a thriving ash growing out of the stone groining over the ground floor amid their rubbish, vegetates at large like a plant in a pot half-filled with soil, and peers over the parapet. A small bell given by Mr Sibbitt of the Greens (the chapel was before without one), hangs in a small turret on the western wall.[3] Raine continues

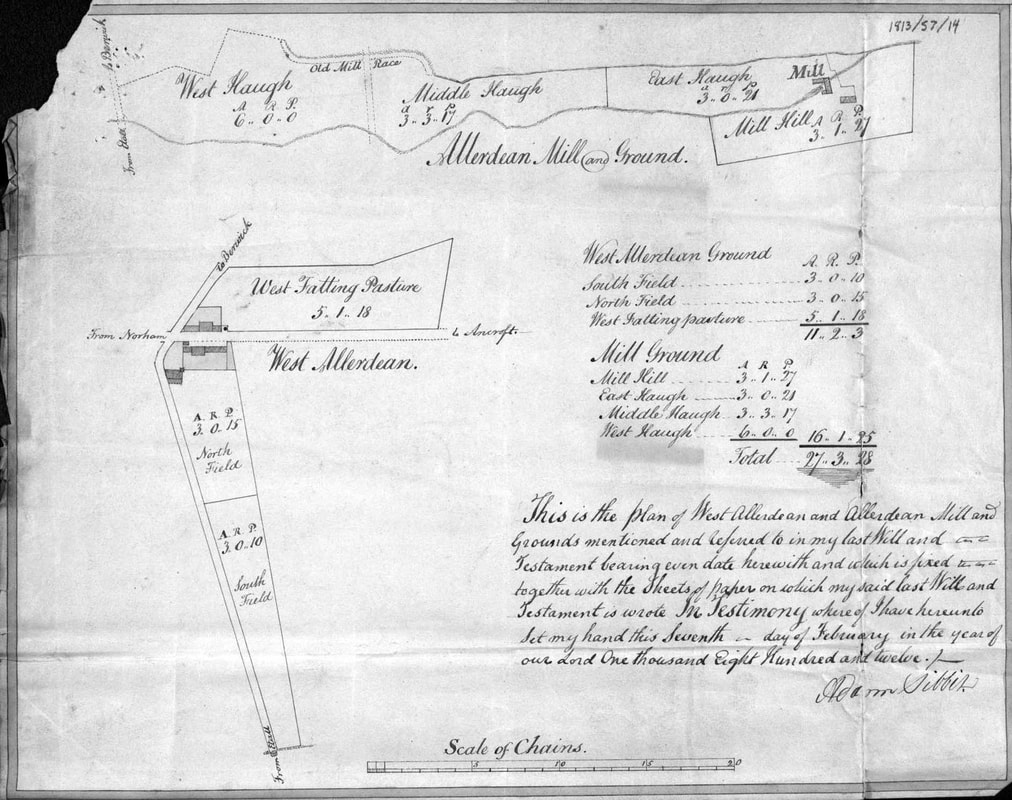

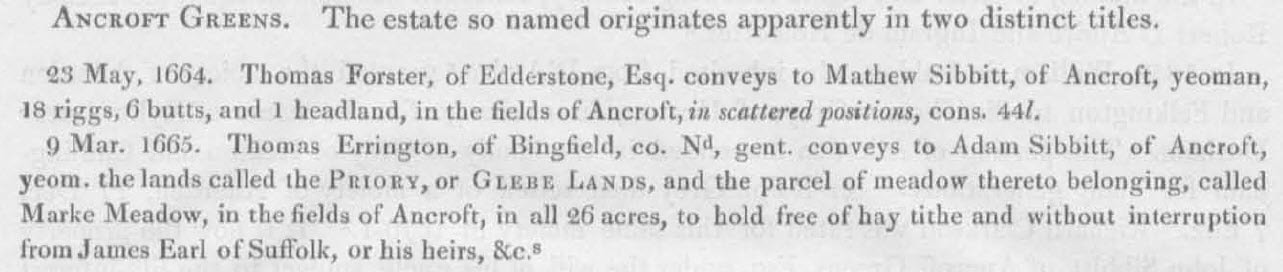

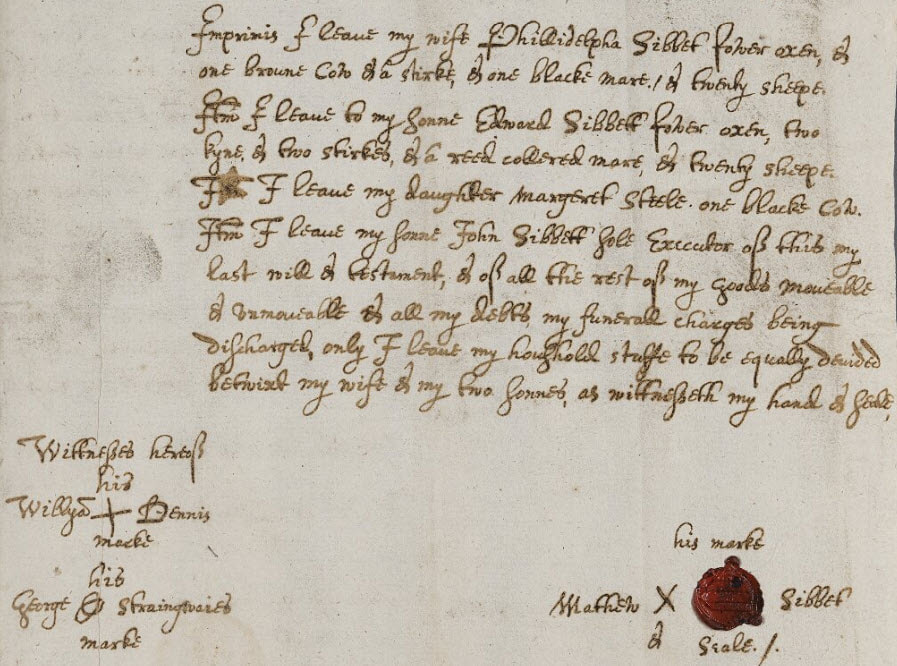

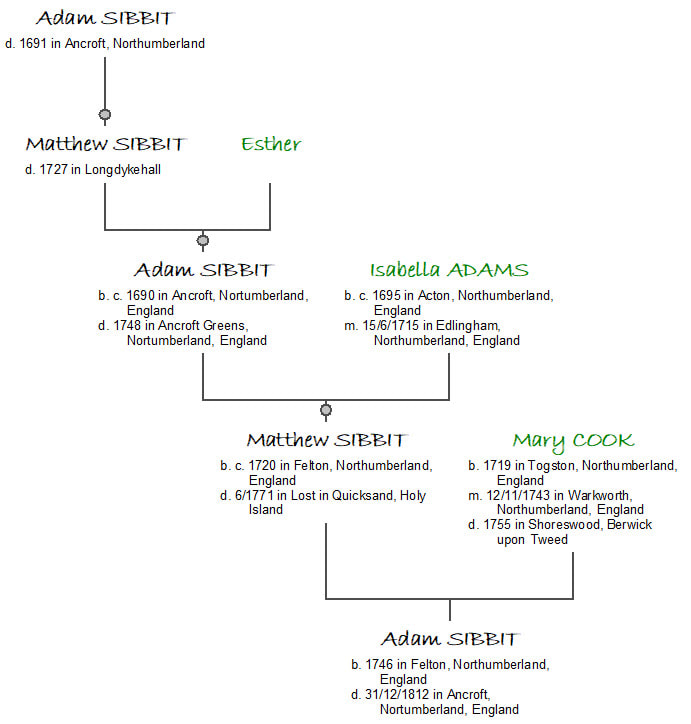

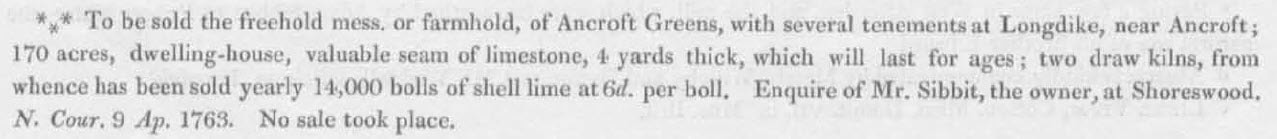

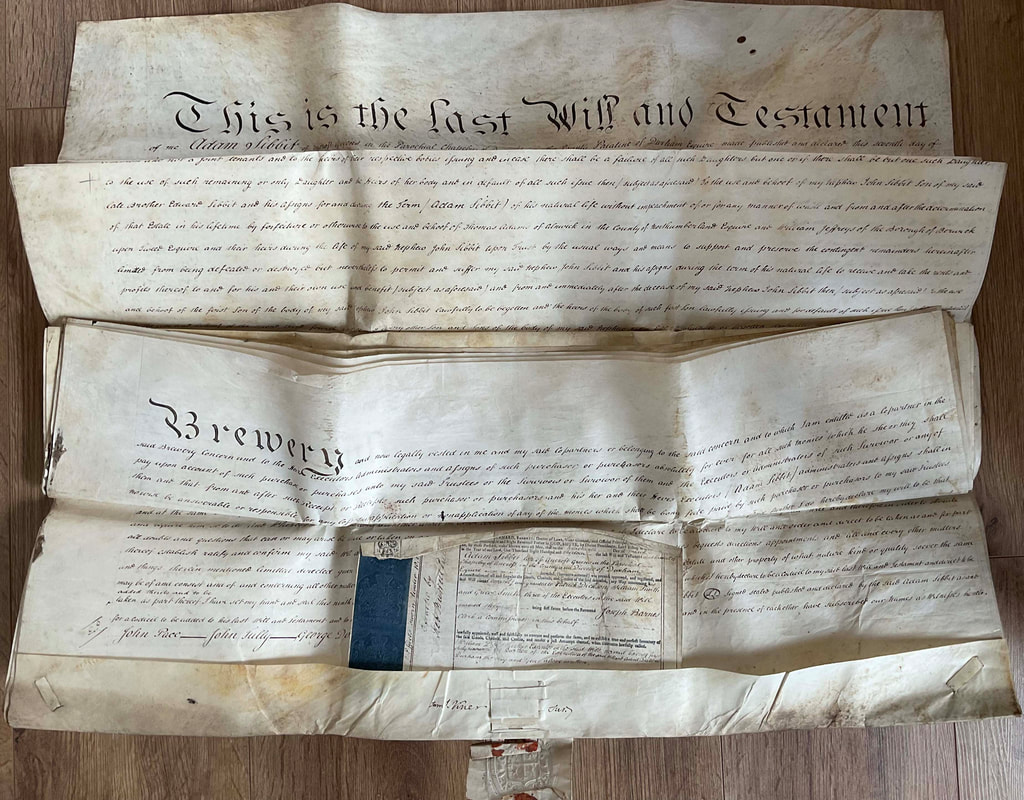

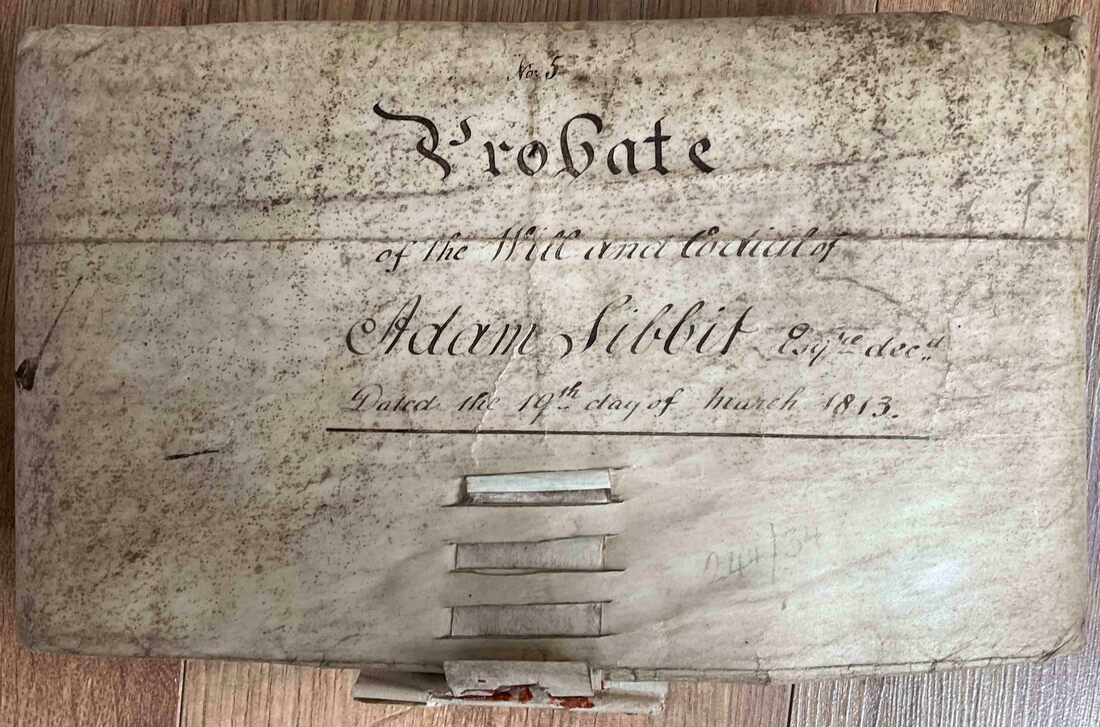

Ancroft Greenses – Adam Sibbit’s homeIt is helpful to note that Ancroft consisted of four townships: Cheswick, Scremerston, Haggerston as well as Ancroft itself. Ancroft township contained three villages of Ancroft, Cheswick and Greenses. Until 1843 Ancroft and associated townships lay in Norham and Islandshire that was part of Durham rather than Northumberland as it is today. (A map showing the extent of the Parish is available through the Parish Council Website https://northumberlandparishes.uk/ancroft/map.) Further extracts from the 1828 Parson and White directory describe Ancroft Greenses, the home of Adam Sibbit as … a village in the township of, and 1 ½ miles NW of Ancroft and 4 miles south of Berwick, where there is a large brewery and coal mine called Unthank Colliery of which J Sibbit Esq is the lessee.[5] Adam’s Will, proved in 1813, contains a detailed description of the house adjoining ‘garden, shrubberies, plantations and pleasure grounds’ that enables visualisation of the layout as it was in his day. With additional outbuildings: back kitchen, laundry business, office and room above the office, a four stalled stable and chaise house and a hovel covered with blue slate, two byres, a dove cott, pig houses, calf hovels and a large yard. Together with a large grass field formerly called Wadeup Close and Dove Cott Close then known simply as the Lawn. As well as other business interests, breweries, quarries, collieries etc., the Will also includes details of his other landholdings at Longdykehall, Allerdean and Allerdean Mill. There were periods when the Greenses was let and times the census bustles with the activity of later Sibbit Families, but slowly their numbers dwindled until just three remained in 1891. By 1901 the only residents were a gardener and general servant. Today, the house at Ancroft Greenses is called Allerdean Grange. As well as the name (which changed between 1901 and 1911) the house has seen several transformations and modifications. But today, possibly barring the render, the frontage appears similar to a photograph dating from the 1880s. The pair of bays must have been a contemporary addition as they are absent in an earlier photograph said to date from the 1860s. A set of sale particulars circa 1991 for the house and adjoining cottage show further modifications to the frontage and east gable end. They describe the house as dating from the seventeenth century and state. The properties reputedly have connections with Cromwell and John Wesley and they undoubtedly retain the charm and character of former times … [6] On census night 1911, a Mr Thomas Chisholm, ‘Landowner' of Scremerston was in occupation at the house now Allerdean Grange, suggesting a change of ownership may have coincided with the change in name. Sibbit land Occupation and Ownership at AncroftThe Grey family held the manor of Ancroft from the mid-fourteenth century. …The whole manor of Ancroft so afterwards passed to the Greys of Heaton and Chillingham, in whom it descended till a partition of the estates of that family was made under the following circumstances. Mary Grey, the only daughter of Ford Lord Grey (who died in 1701) and the wife of Charles Bennet, the first Earl of Tankerville, claimed all the estates of her father as his heir. Her uncle, Ralph Grey, Governor of Barbados, who had succeeded to the title of Lord Grey of Wark upon the death of his brother, her father, put in a similar claim under a settlement of his grandfather, William the first Lord Grey. The question after somewhat of litigation was compromised by a partition of the estates. Regardless of the Grey monopoly, pockets of Sibbit ownership at Ancroft begin to appear in documents dating from the mid-seventeenth century. But still earlier links to the village and its surrounds are proven through the Inventory of John Sibbit of Ancroft dated 1631. Administration was granted to his son Matthew Sibbit of Ancroft who in turn died the 8th February 1640. His Will of 1639 provides evidence of his wife Philadelphia, a daughter Margaret, married name Steele, and two sons Edward and John. Son John died at Ancroft Mill in 1682 and his Will names sons Matthew and Thomas, daughters Phillis Archbald, Elizabeth Dodds, Elinor Sibbit and two grandchildren. His Will was witnessed by Adam Sibbit of Ancroft and although the exact degree of kinship between John and Adam is not yet known, they were almost certainly related. This Adam Sibbit died in 1691 and also left a detailed Will. It is from him, that Adam Sibbit of Greenses House and owner of the burial vault descends through a succession of eldest sons. (With Adam Sibbit who died at Ancroft Greenses in 1812, this line of at least five successive generations of inheritance by the eldest son came to an end.) The Estate papers of the Howick Estate, held at Durham University Archives, also contain evidence of Sibbit occupation and bolstering of land holding and farming interests through rental.

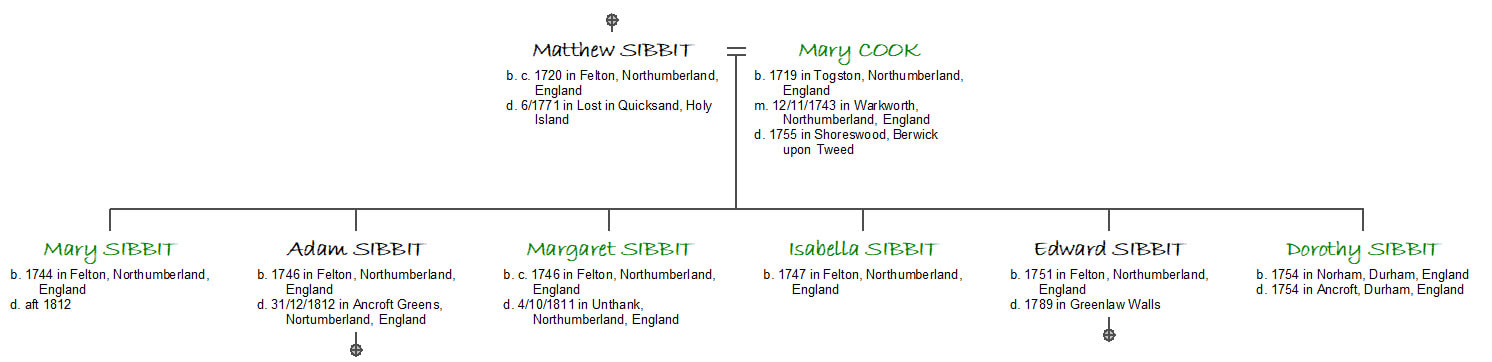

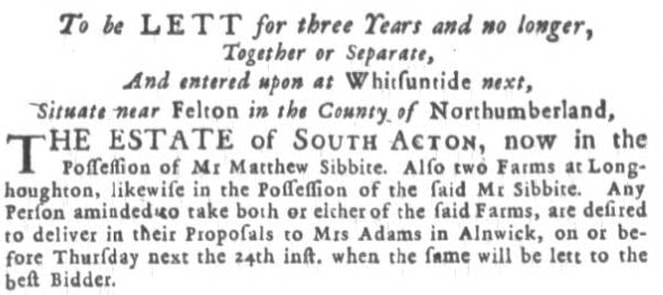

This collection relating to the Grey’s Northumberland Estate, referred to as the ‘Howick Estate’ contains important historical information. As well as Ancroft, the estate included farms at Howick, East and West Learmouth, Downham, Presson, Tithe Hill and Howburn on Tweedside and the Chevington Estate south of Howick in mid-Northumberland. … Besides these there were a few more isolated properties such as Cold Martin in the Parish of Chatton, Fleehope in the Cheviots, Burton in the Parish of Bamburgh and Budle on the coast. The records contain …deeds of some of the Northumberland properties which date from the sixteenth century, [including some relating to Ancroft] most of the material falls into the period 1780-1930, but numerous items will be found both before and after these dates. Making them a rich and valuable source for researchers. In addition to Inheritance and Estate information, the newspapers also bear evidence of land, farming and business interests further afield, including Alnwick, Felton and Longhoughton. Doubtless, as research continues, more places, partnerships and interests will come to light. A Bit About AdamAdam was baptised at Felton the 5th June 1746, the eldest son and third of six children, 4 girls and 2 boys. His father was Matthew Sibbit and his mother Matthew’s first wife Mary Cook. Matthew Sibbit farmed at South Acton, near Felton, possibly where he was born, circa 1720. The farm formed part of an estate owned by the Adams family to whom Matthew was connected through his mother, Isabella Adams. At the baptism of Dorothy Sibbit at Norham in 1754, their father Matthew is described as of Shoreswood. This suggests the farm of South Acton was successfully let following an advertisement in the Newcastle Chronicle in 1751. Adam’s mother died when he was nine years old and his father married his second wife Hannah Selby, daughter of Captain Gerard Selby of Beal and Holy Island at Belford in November 1757. The couple provided Adam with a further five half-siblings, although two died in infancy. All the baptisms of this second brood also took place at Norham whilst Matthew resided at Shoreswood and where he remained until his death. An apprenticeship enrolment for Adam’s half-brother Matthew to James Bell Burgess and Merchant of Berwick in 1774, describes Matthew as late of Ancroft Greenses, suggesting the continuation of the family’s interest. In the 1760s, notices advertising the sale of Ancroft Greenses begin appearing in the press, although it was clearly never sold. It is not yet known why, but the notices continue to appear through to 1774, after Matthew was lost in quicksand off Holy Island in 1771. The administration of his estate was undertaken by Adam as his eldest son, along with William Smith of East Newbiggin (of whom more in Part II) and George Robinson of Ancroft. In the renunciation by Matthew’s widow, annexed to the Will she refers to Adam as of Ancroft Greenses. Little is known about Adam’s formative years such as where he was educated etc. but he undoubtedly spent much of his childhood at Shoreswood. To date, the next sighting of him is in the Norham parish register of 1768 where on 3rd June he and Barbara McDugil [sic] of Thornton baptised a daughter Margaret. Little would the 22-year-old Adam have known at the time, but this would be the only child he would father. In November 1773 Adam married his half first cousin Isabella Yelloly at Belford. Isabella’s mother Margaret Sibbit was half-sister to Adam’s father Matthew Sibbit as the pair shared a mutual grandfather in Adam Sibbit senior. In 1794 Adam and a member of the Yelloly family were noted to have interests in Maltings and Brewery in Walkergate, Alnwick. This would be in addition to his other interests in a large Brewery at Berwick. Adam and Isabella were married for 38 years but the union was not blessed with children. Isabella pre-deceased her husband by a matter of months. She died at Ancroft in April 1811 and he on Old Years Night in 1812. Yet he still found the time to marry again in the intervening period. His second wife Hannah Brankston was aged 43 at the time of her marriage, some 22 years her husband’s junior. So, although still possible to bear a child, her age at marriage suggests the desire for an heir was not an overwhelming factor. In terms of tracing his closest blood relatives, his illegitimate daughter Margaret and her children are his only known direct descendants. Margaret and her husband Robert Dunlop are mentioned in Adam’s Will, although her mother is named Barbara McDonald rather than McDugil [sic] as per the Norham Register. She also received a small bequest I also give and bequeath unto Margaret Dunlop Daughter of Barbara McDonald and now the wife of Robert Dunlop of Slainsfield in the Manor of Etal and County of Northumberland Colliery Agent or Bankman the sum of five hundred pounds of lawful money.[11] As did her children, to be paid when they reached 21 years of age … Then I do hereby give and bequeath the said legacy or sum of £500 to all and every of the Children of the said Margaret Dunlop in equal proportion share and share alike… Indeed, Adam’s Will comprehensively encompasses many of his remaining relatives. I find myself warming to him as I read as he leaves provision for many of his siblings nieces and nephews. One of the main beneficiaries under his Will was Robert Sibbit, eldest and ‘the natural son’ of his brother Edward. There will be more about the pedigree, the people and their stories at the end of next month in Part 2. Some of whom have taken a globe-trotting route back to Tweedside - think Scotch Herrings ‘in prime order’, barrels of salt beef, pork and ox tongues by the half keg shipped from London and Cork on sale in Jamaica in 1793... To be continued ... Footnotes & Links[1] Sarah Hoiles, ‘Early Victorian Coffins and Coffin Furniture’

https://cemeteryclub.wordpress.com/2013/11/07/early-victorian-coffins-and-coffin-furniture/ [2] WM Parson and WM White, Vol II of the History, Directory and Gazetteer of the Counties of Durham and Northumberland etc., 1828 https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_MbA3AAAAYAAJ/mode/2up [3] ‘Monumental Inscriptions. On a monument affixed to the north wall of the nave: “Sacred to the memory of Isabella, wife of Adam Sibbit, Esq. of Greenses House, who departed this life April 7, 1811, aged 64 years. Also, to the memory of Adam Sibbit, Esq who closed an industrious and benevolent life the 31st day of December 1812, in the 67th year of his age’. Rev James Raine, The History and Antiquities of North Durham, 1858. [4] Rev. James Raine, The History and Antiquities of North Durham, 1858. P.217 [5] WM Parson and WM White, Vol II of the History, Directory and Gazetteer of the Counties of Durham and Northumberland etc., 1828 https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_MbA3AAAAYAAJ/mode/2up [6] Berwick Record Office, (BRO 1016/4) Particulars relating to the sale of Allerdean Grange circa 1991. [7] Rev James Raine M A, ‘The History & Antiquities of North Durham’, London, 1852. [8] Durham University Archives, GRE/X/P75, 1734-1762, Farm Leases. [9] Durham University Archives, GRE/X/P79 , 1802-1845, Farm Leases [10] Durham University Archives, Estate records of the Earls Grey and Lords Howick 1522-1980. https://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/view?docId=ark/32150_s1gf06g268w.xml [11] North East Inheritance Database, (DPR/I/1/1813/S7/1-27) http://familyrecords.dur.ac.uk/ by Richard HoltThe author of this month's blog is Richard Holt, professional genealogist at Holt's Family History Research. Richard is latest addition to the #AncestryHour team of experts providing help and support during our live Twitter sessions. Based in Cambridge but born in Buckinghamshire, his geographical expertise and specialist interests will add a new dimension to the Tuesday evening get-togethers. To find out how #AncestryHour's thriving community could help your research move forward head to our 'About' page or contact us for more information. ***** Wednesday 3rd February 1909: ‘Found Dead’ in St. George and the East Workhouse ... The body of Thomas Buyrns, aged 79, was found dead in the St. George and the East Workhouse on Raine Street, Wapping. An inquest followed on 5th February conducted by Wynne Edwin Baxter, Coroner for the County of London. Baxter was the Coroner who conducted the inquests for the Jack the Ripper victims as well as the inquest into the death of Joseph Merrick (1862-1890), who was known as ‘The Elephant Man’. The inquest determined that the death was of natural causes with the cause being given as syncope, cardiac degeneration and bronchitis. [1]. This story was the catalyst for my love and appreciation of the Admiralty records. Thomas Buyrns (1830-1909) was my third great grandfather, and it was locating his death that set me on a path of discovery. Thomas was formerly a stevedore; a person employed at the docks to load and unload ships. While this occupation was linked to ships, Thomas’ connection to the Admiralty was still shrouded in mystery. Thomas’ death certificate recorded his name as ‘Thomas Matthew Dunmore Buyrns’. While I had come across the name Thomas Matthew Buyrns in many records, this was the first time the name ‘Dunmore’ had appeared. The name ‘Thomas Matthew Dunmore Buyrns’ was the breakthrough I needed to take this family line further back in time and discover the immensely fascinating history of this family. Thomas Buyrns had married twice, although the information in both parish register entries was confusing and contradictory. The first marriage to Sarah Cocks on 7th May 1854 claimed that Thomas’ father was Thomas Buyrn a Butcher; while the second marriage to Caroline Way on 31st October 1869 claimed his father was Matthew Buyrn a Marine. I was not able to locate anybody with these names that matched the claimed occupations. This was a veritable ‘brick wall’. One of the tools in any genealogist’s tool box should be the ‘archive catalogue’. I would not be able to do my job without regularly referring to the catalogues from hundred of archives. Helpfully, many archive catalogues are pulled together on The National Archives’ catalogue ‘Discovery’.[2] It was searching here that I came across the entry for ‘Thomas Matthew Buyrn Dunmore’ amongst the application papers to Greenwich Hospital School (ADM 74/217/90) It was pursuing these application papers and the surviving Bishop’s Transcripts for East Stonehouse, Devon that led me to the conclusion that Thomas’ father was named Matthew Buyrn, but had in fact joined the Royal Marines in 1812 under the name John Dunmore. The application papers, along with those for two of Thomas’ siblings, provided information in relation to John Dunmore’s service history. This was the breakthrough needed to advance my research. I wrote about name change under the blog post ‘Matthew Buyrn or John Dunmore?’. (You call also read about some of Matthew Buyrns’ life after he was discharged from the Royal Marines in ‘Life After the Royal Marines - Theft, Fraud and Imprisonment’.) Navigating the Records - Royal MarinesThere are a wealth of Admiralty records held at The National Archives. If you’re lucky enough to come across a record detailing the service history of a Royal Marine or someone in the Royal Navy, this will give you a head start. It can often be quite daunting knowing where to start looking for information. For example, within ADM 1, there are 31,116 files and volumes alone. I will outline a few of the key places to look for information about an ancestor’s service history using my ancestor ‘John Dunmore’ as a model. While John Dunmore was in the Royal Marines, some of these records apply to researching individuals who were in the Royal Navy. I will try to outline when this is the case. The first place to look for a Royal Marine would be the Attestation Forms in ADM 157 which covers the years 1790-1925. Please note that not all Attestation Forms survive, as is the case with John Dunmore. There is a search function which allows you to search by keyword and you can enter the name of the marine here. If the Attestation Form does not survive, I would suggest consulting the Description Books in ADM 158 which summarise information given in the Attestation Forms and are therefore a useful substitute. If using the Description Books, you will need to know the Division to which your ancestor belonged. This can therefore make things more challenging if this is not known. If you happen know their Company number, you can use the fold-out appendix in Thomas Garth’s ‘Records of the Royal Marines’ to find out the Division.[3] Helpfully, the entry for John Dunmore’s attestation in the Description Books showed his age, occupation and that he was born in Edmonton, Middlesex. For many people, knowing the name of one of the ships that their ancestor served on is the only point of entry for reconstructing a service history. If you have the name of a ship, the muster rolls can be searched to locate the individual. Once located, the muster rolls can be searched backwards and forwards to find the dates of admission to, and discharge from the ship. These records are found in ADM 36, ADM 37 and ADM 38. The musters will usually name where the individual was admitted from and discharged to, thus allowing these leads to be followed up in other records or the muster rolls of other ships. The muster table at the front of each muster will also give the places where the ship was located at various times. It is useful to look under the various categories of individuals in the muster, as sometimes an entry may be found under the list of supernumeraries. The muster books also record promotions, so these can be used to find out how your ancestor rose amongst the ranks. The musters sometimes record an individual’s place of birth along with their age. Additional records that provide more information on the day-to-day life onboard the ship include the various ships’ log books.[4] The other place to look for information is in the Effective and Subsistence Lists held in series ADM 96. These are lists of individuals who are not currently serving on board a ship and they show the subsistence pay received during this time. The earlier records are on large printed sheets of paper, but the latter records are in book form. They record ‘from whence’ a person came, often naming a ship. When an individual was removed from the list, the ship they were admitted to will be recorded. If they were not admitted to a ship, the reason for removal should be noted. These records are also arranged by Division and Company. The following example is from the ‘1st Company’ to which John Dunmore belonged. It is my belief that these records are often an underused source of information. They are not catalogued very well and can be difficult to use, however they do provide a steppingstone, allowing the researcher to trace an individual’s service history more accurately. The Allotment Registers are another key source of information, particularly if you’re lucky enough to have an ancestor who allots part of their pay to a family member. These are found in ADM 27 and contain details on individuals who were in the Royal Marines as well as in the Royal Navy. An entry in the Allotment Registers will record details such as the number of children that the individual had, the name of the relative they are allotting their pay to, along with their relative’s place of residence. When an individual’s ancestry is unknown these records can be particularly useful. John Dunmore was on board the HMS Bramble in 1825 when “the Articles of War, and the Abstract of the Acts of Parliament were read to the Ships Company” (ADM 37/7064). The sources discussed above are only a very small number of records that can shed light on your ancestors. While some relate only to Royal Marines, others contain details of those in the Royal Navy as well. There are also many other records in other collections, such as the War Office collections, where information relating to John Dunmore’s pension is found. For a thorough guide to naval records, please see Randolph Cock and N. A. M. Roger’s guide ‘A Guide to the Naval Records in The National Archives of the UK’ which can be downloaded free of charge as a PDF file. [5] Endnotes[1] Certified Copy of an Entry of Death, Thomas Matthew Dunmore Buyrn, General Register Office, March Quarter, St George in the East Registration District, Volume: 1c, Page: 1909. [2] Discovery, The National Archives, available at: https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/, accessed: 22nd June 2022. [3] Garth, Thomas, Record of the Royal Marines, PRO Publications, 1994. [Note: The fold-out appendix is between pages 54 and 55.] [4] How to look for records of… Royal Navy ships’ log books, The National Archives, available at: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ships-voyages-log-books/, accessed: 22nd June 2022. [5] Cock, Randolph & Rodger, N. A. M, A Guide to the Naval Records in The National Archives of the UK, The Institute of Historical Research and The National Archives, 2006. Other Useful Guides and Information

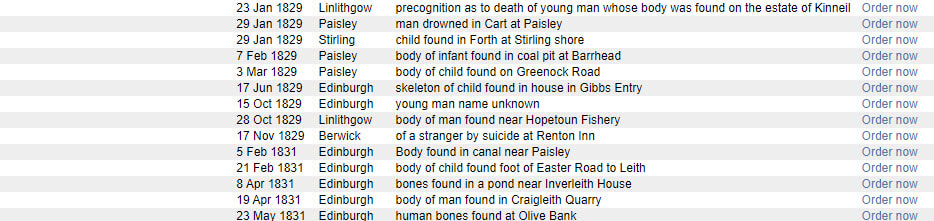

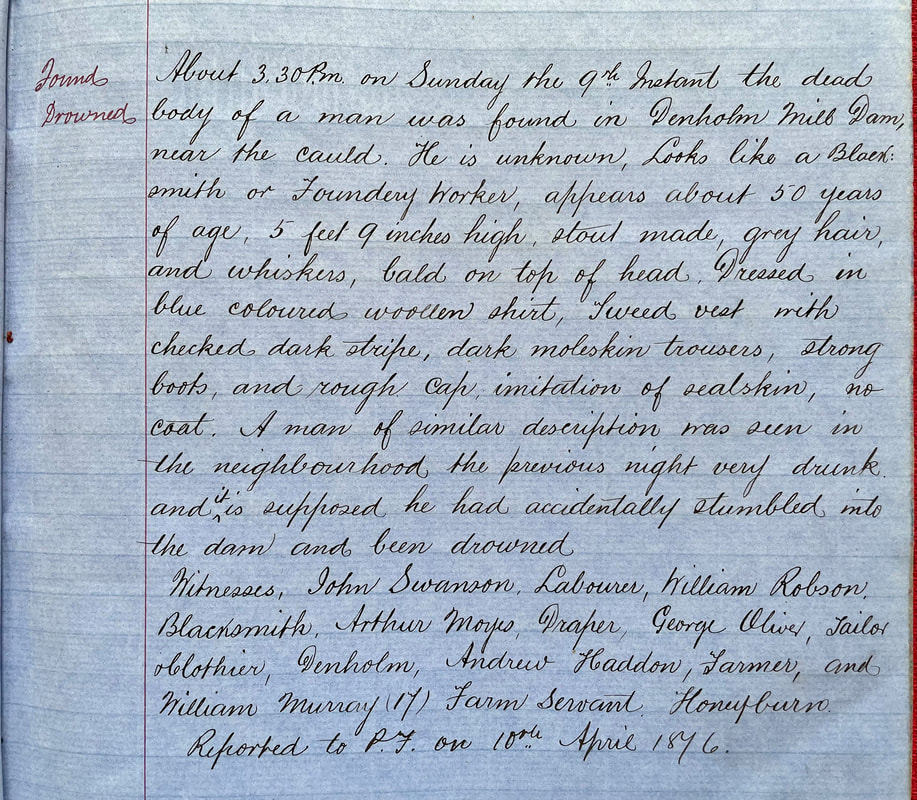

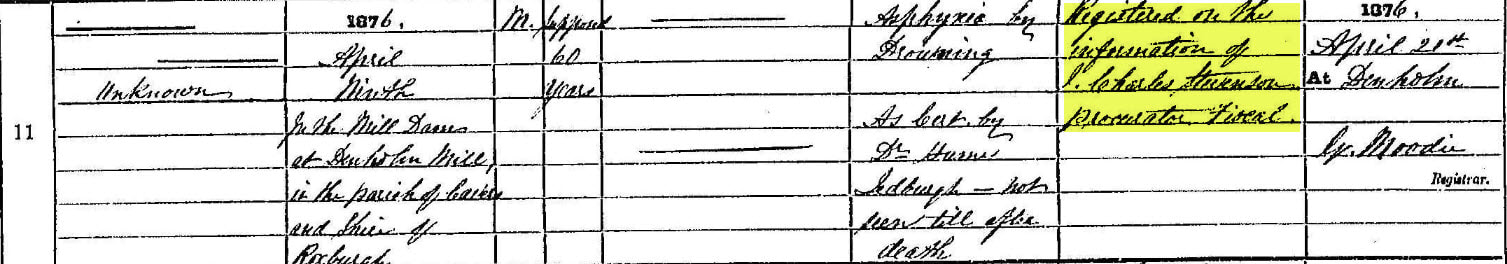

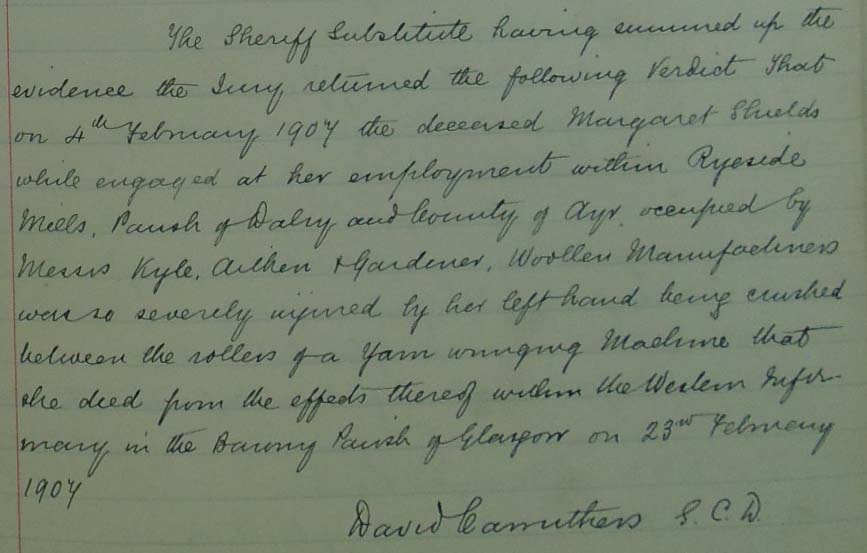

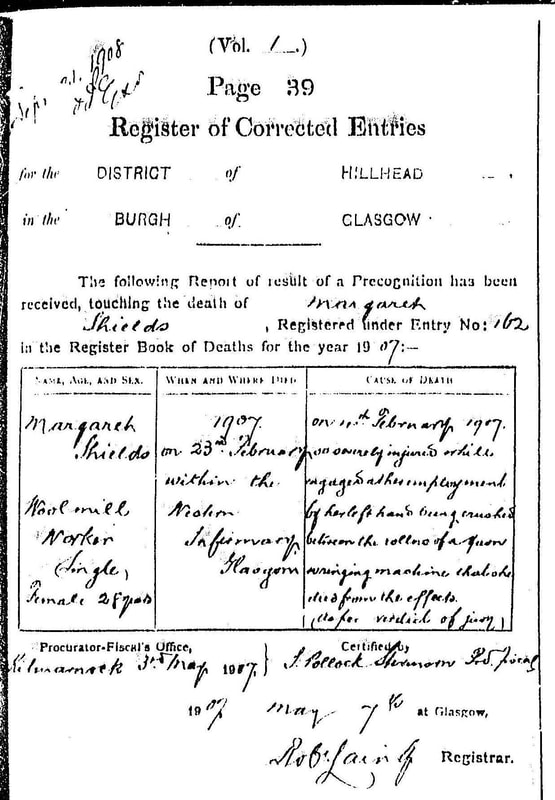

Six years have passed since I last penned a piece about death and its associated records. Although ‘Dispatches’, is as relevant now as it was back in August 2016, there are a few sources and cross-border peculiarities relating to the recording of sudden, suspicious or unnatural deaths and accidents that were not covered at the time. Below are eight of the more unusual departures encountered to date:

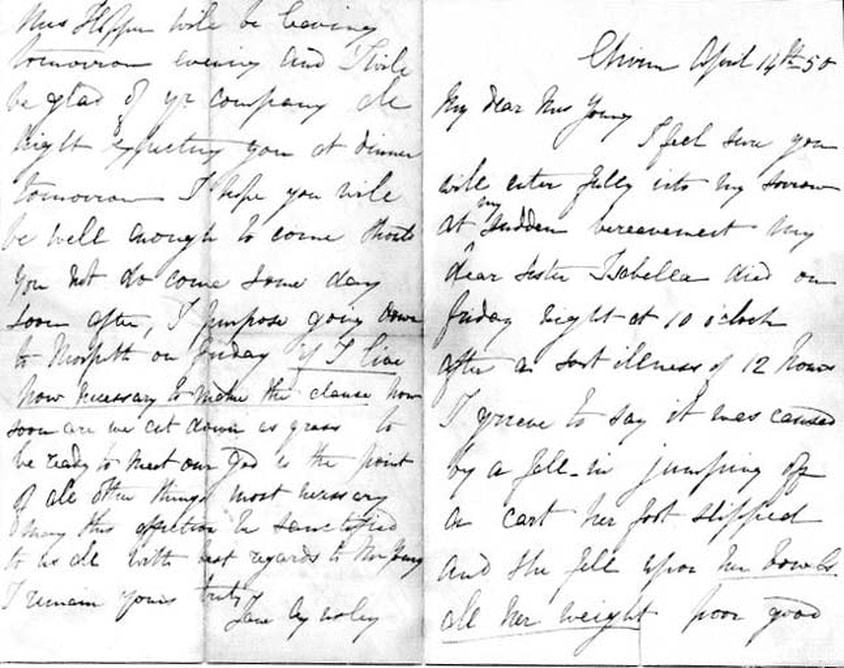

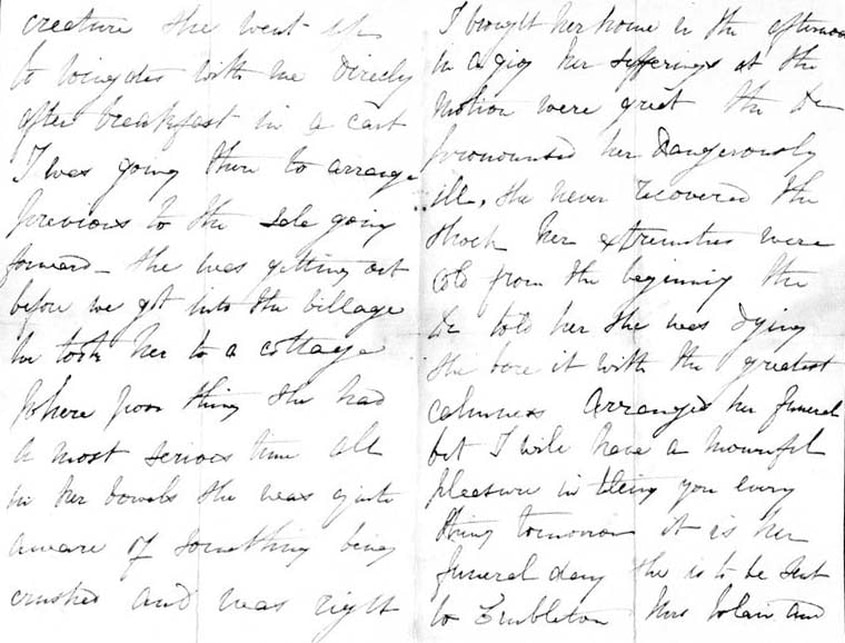

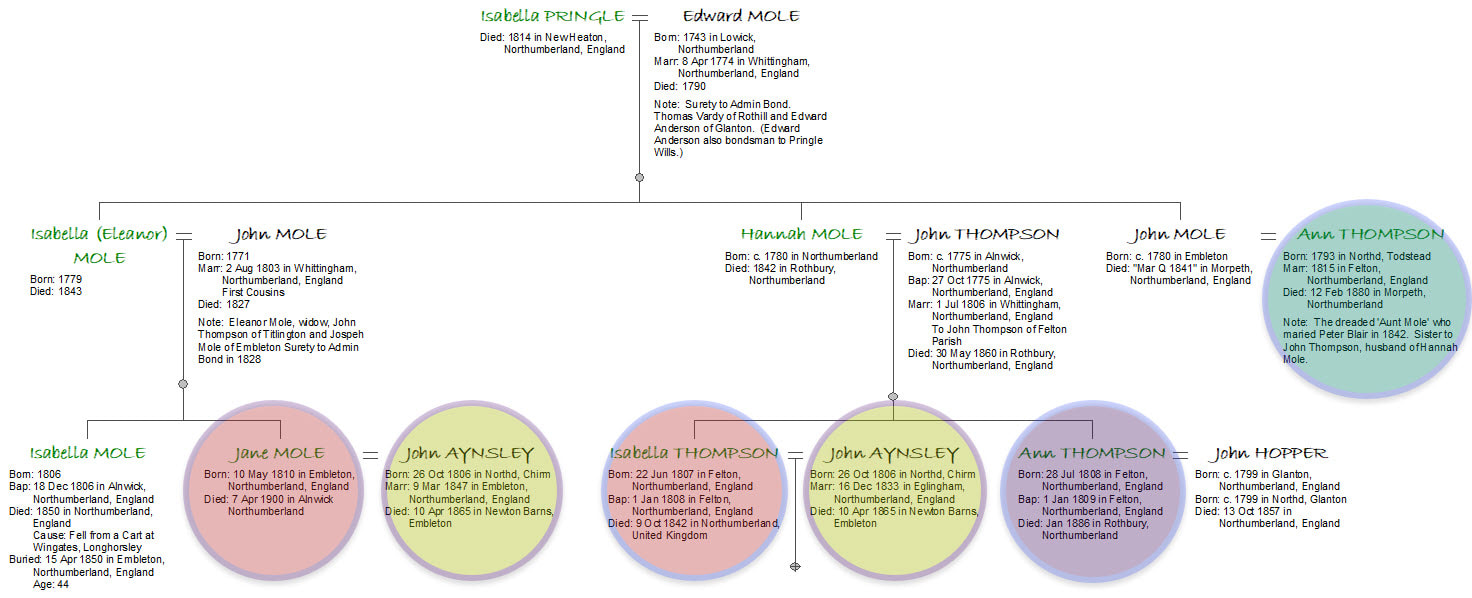

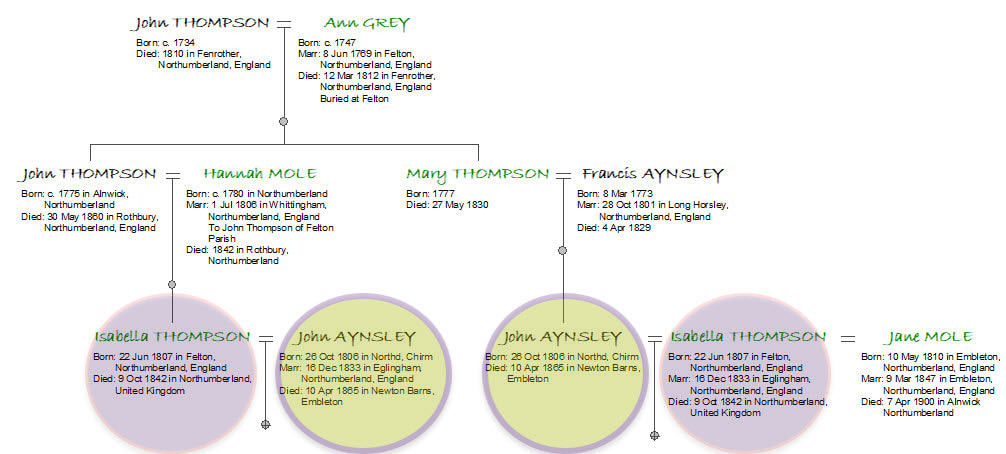

There have been many more encounters with unusual departures since then too. Amongst them, in the collection of family letters, there is the harrowing account of the death of Isabella Mole (A 1C5R to me), who ruptured her bowels in a fall from a cart at Wingates near Longhorsley in 1850. Chirm April 14th [18]50 Jane Aynsley nee Mole (1810 – 1900), was the second wife of John Aynsley, farmer at the Chirm Longhorsley. She is writing to Ann Young nee Whittam, wife of Alexander Young of Swarland East House - a cousin to John Aynsley’s first wife, Isabella Thompson. Isabella was the daughter of John Thompson, the only surviving brother amongst the many ‘Thompson Sisters’ who, in my efforts to trace living descendants, are the subject of my two previous blogs. Isabella Thompson and Jane Mole were both granddaughters of Edward Mole and his wife Isabella Pringle making them first cousins. Other players in the letter are:

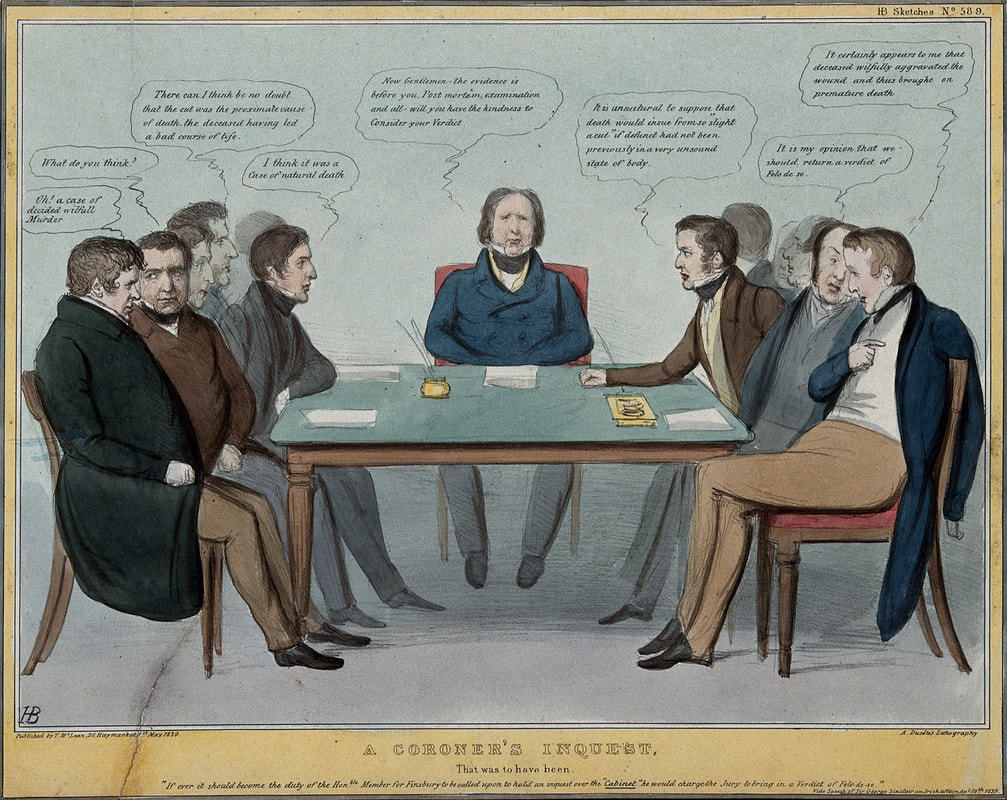

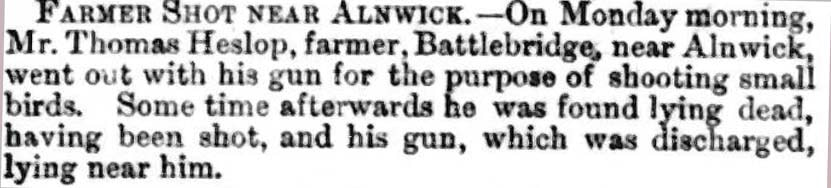

Miss Mole’s demise, like those listed above, was due to accident or ‘misadventure’. In England, deaths in cases of sudden or unexplained death would be referred to the Coroner and if required an inquest held to establish the cause of death. The Coroner The office of Coroner dates from 1194. They are Crown Officials employed to investigate ‘sudden, unnatural or suspicious deaths and the deaths of people detained in prison …’[1] These also include accidents. Coroner’s Inquests, held before a jury up to 1926 were, and still are, public hearings. Historically, venues for inquests were often a local Public House or Inn. Where they have survived, historic records of Coroner Inquests will contain:

From 1487 until the middle of the eighteenth-century, Coroners presented their inquisitions before the Assizes (or in the case of Berwick upon Tweed, the Quarter Session Court.) If the death was the result of a crime, the coroner’s report served as an Indictment. But even where no crime or trial took place, or in cases of accidental death, the records were filed with relevant court papers. However, the survival of records, especially between 1850 and WW2 are limited and patchy at best. Berwick upon Tweed has a run of early documents held locally under reference BA/J. BA/J/QS relates to the ‘Records of the Berwick upon Tweed Quarter Sessions including Criminal and Civil Jurisdiction’ from circa 1600 and BA/J/CO, covers the ‘Berwick upon Tweed Coroner Court, Inquest Warrants and Coroners Inquisitions’ (1745 – 1942). For records from elsewhere The National Archives holds early records (1228 – 1426) under JUST 2 Coroners' Rolls and Files, with Cognate Documents.

Where an indictment did not result in a trial for murder or manslaughter, the inquisitions were forwarded to the King’s Bench. With exceptions (Chester and Duchy of Lancaster), KB9 holds records from 1485 – 1675 for counties outside of London and KB11 for outside of London from 1675 until the mid-eighteenth century. ‘Whilst some records heard before the King’s Bench survive from 16th century, it is believed that all early records from North Northumberland have been lost.’[4] KB10 contains the records for London and Middlesex.

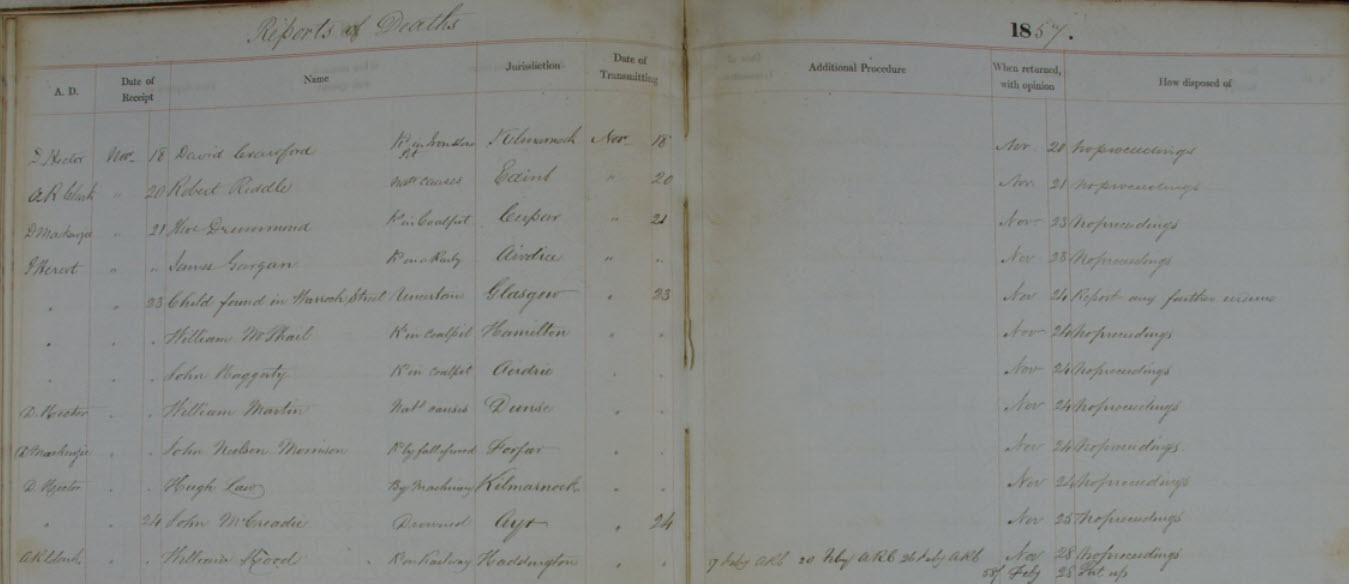

Sudden Death & Accidents in Scotland: |

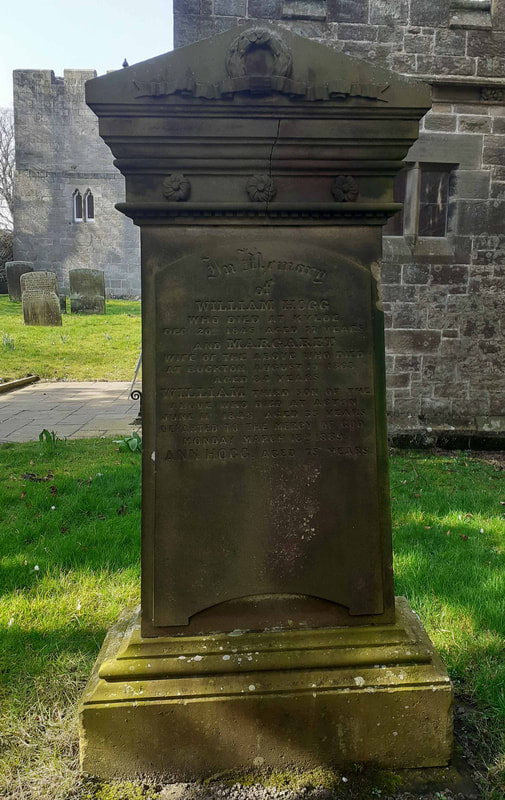

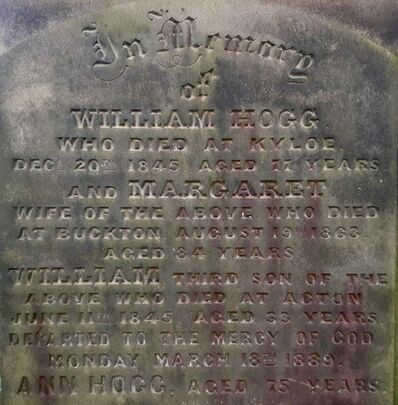

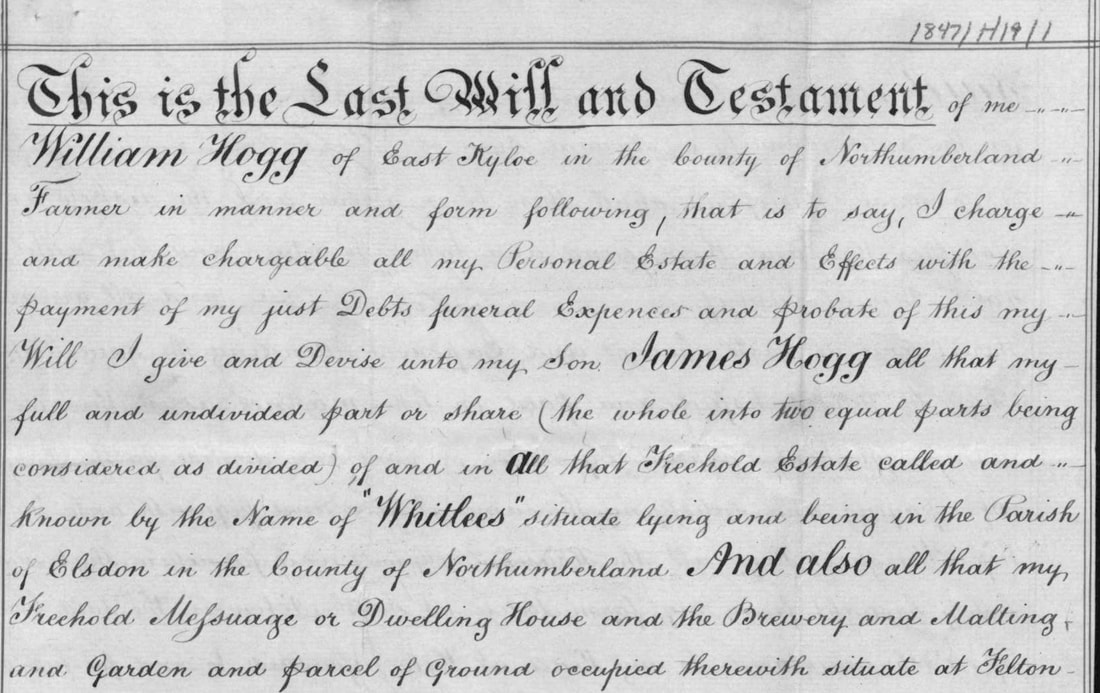

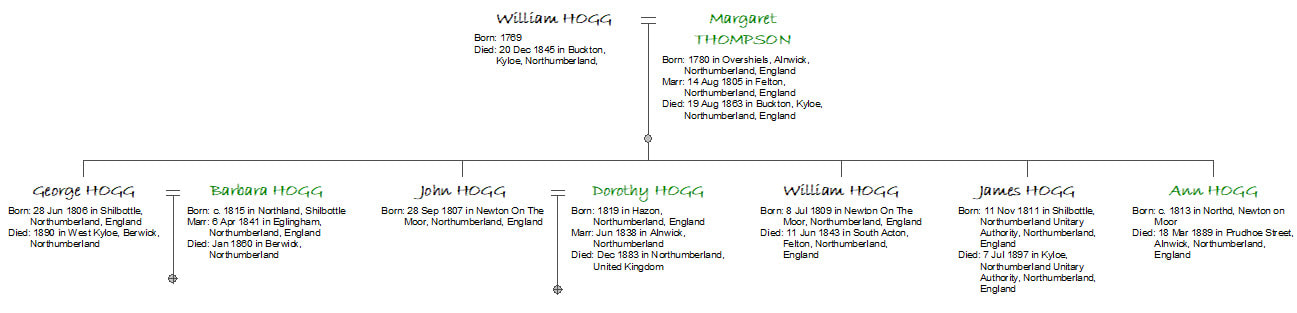

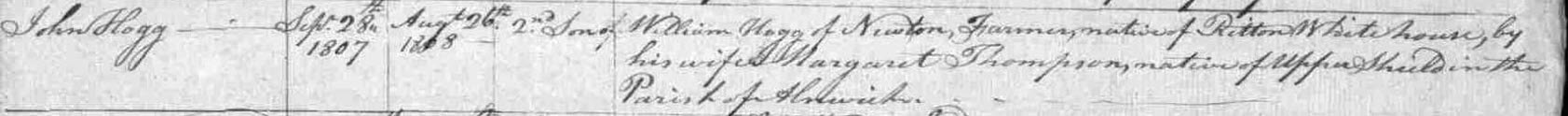

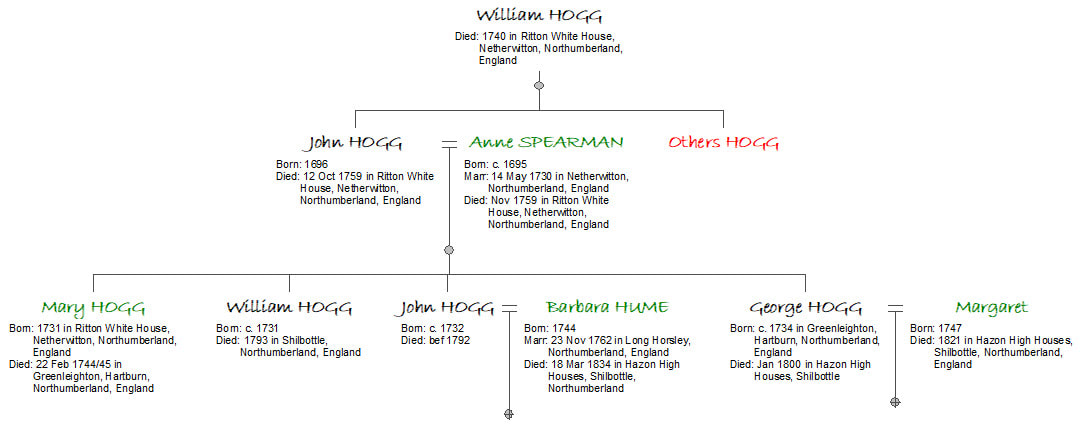

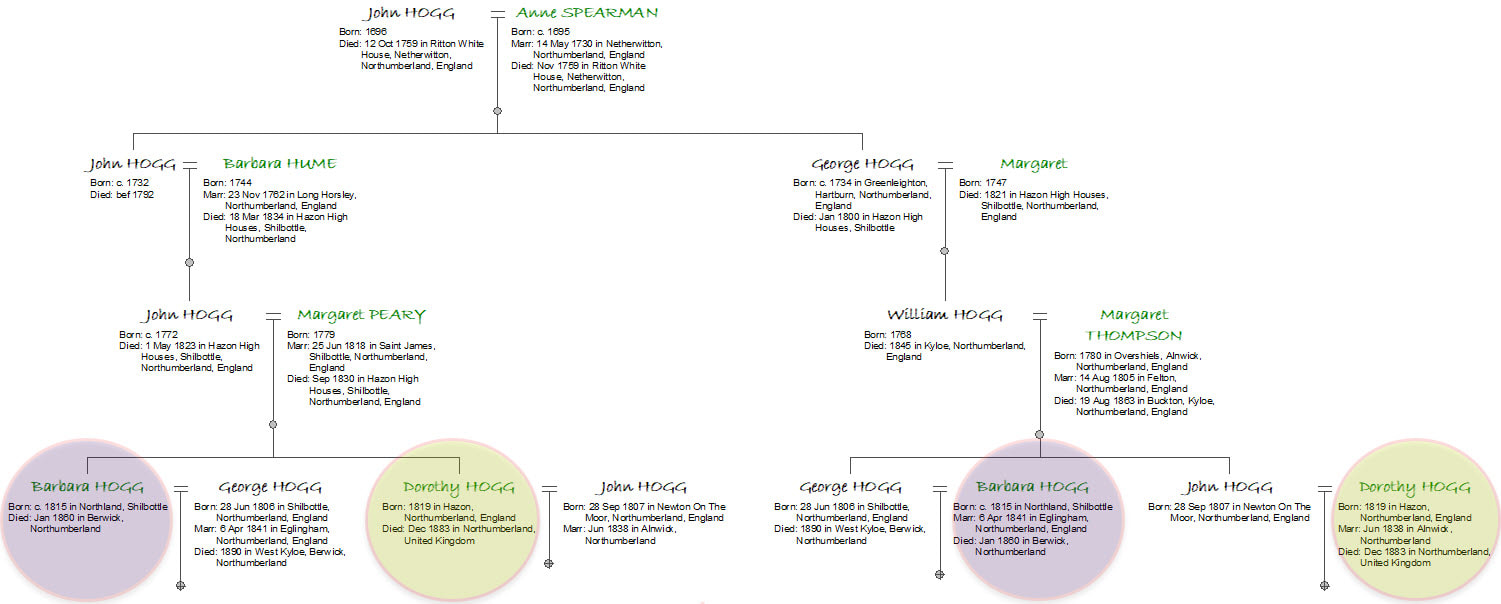

| John Hogg | George Hogg |

| Marriage

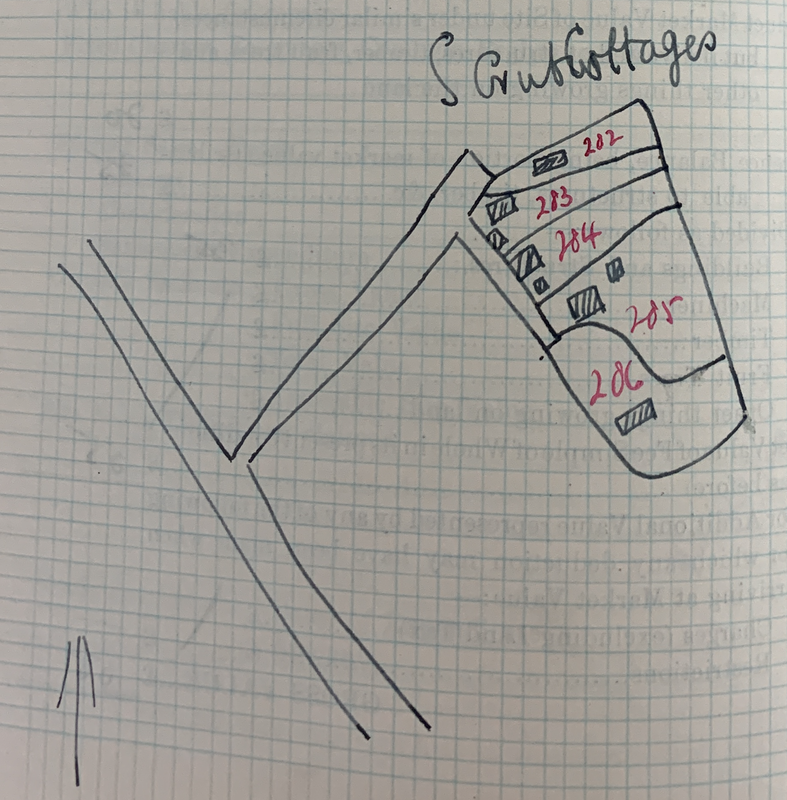

| Marriage of George Hogg.

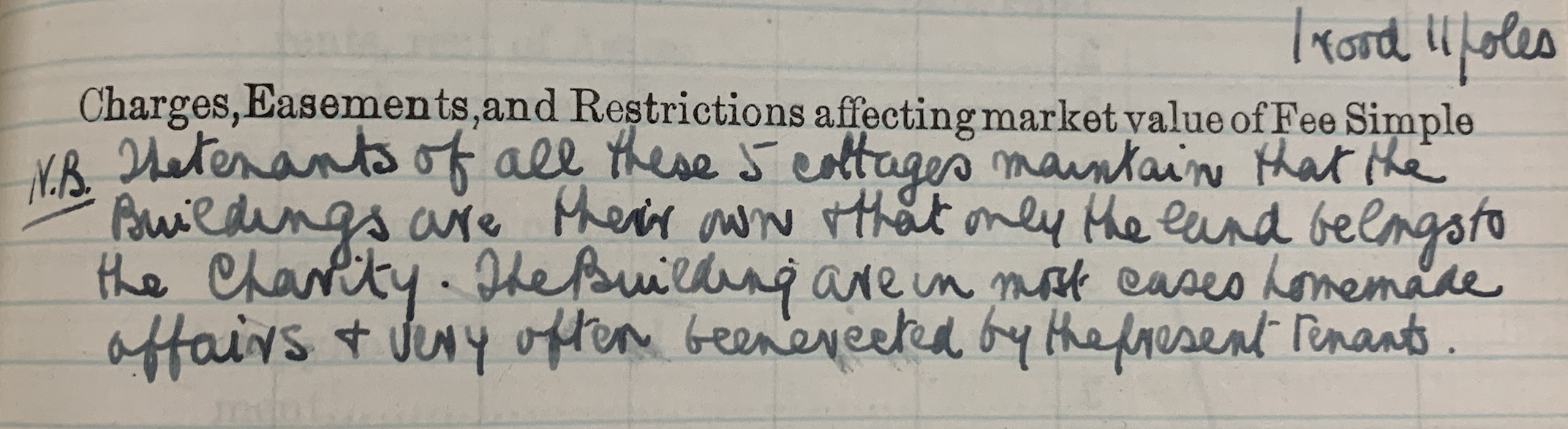

|

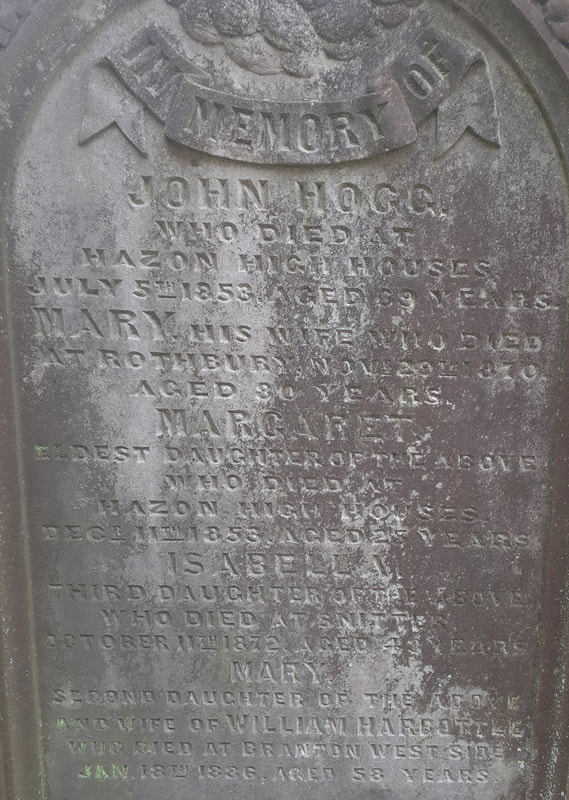

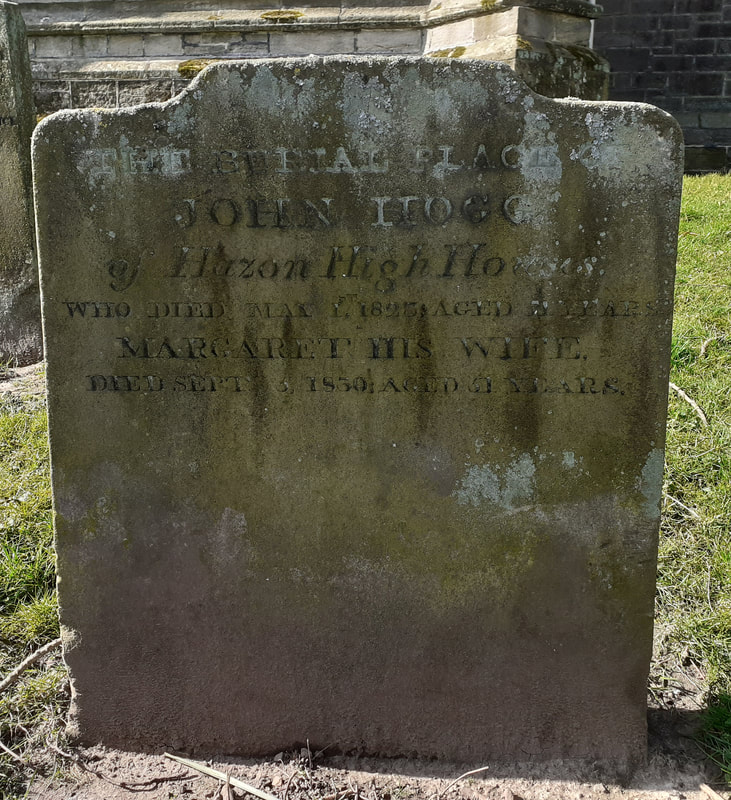

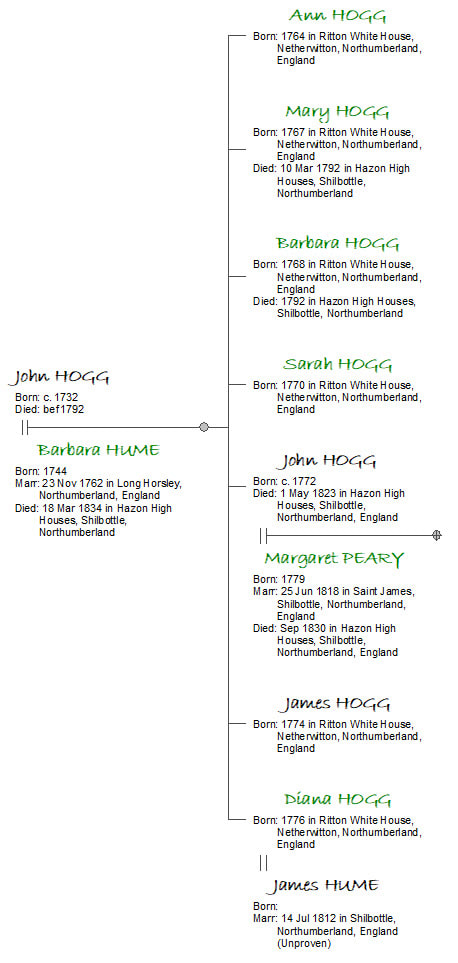

| Children of John Hogg & Barbara Hume | Children of George Hogg and Margaret |

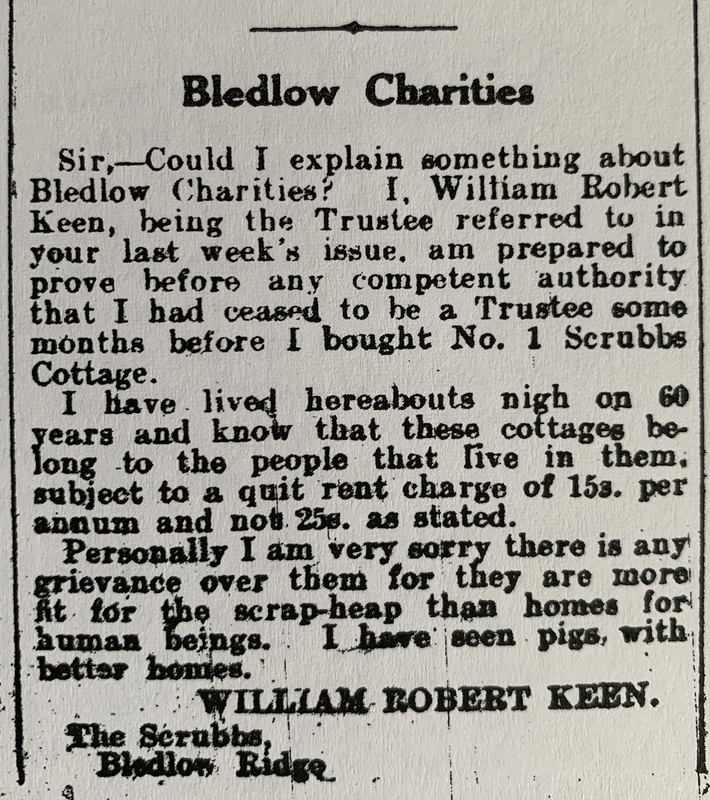

| Death of John Hogg husband of Barbara Hume

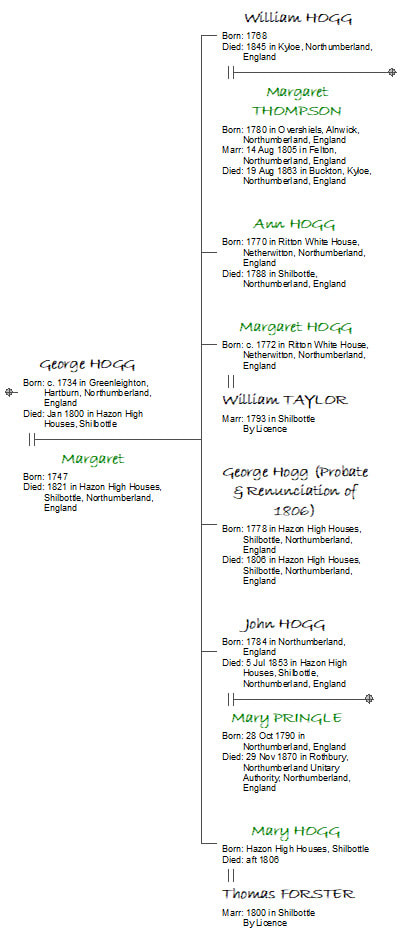

| Death of George Hogg and Margaret

|

Step 10. Further Inter-family Connections

https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=-oYHAAAAQAAJ&rdid=book--oYHAAAAQAAJ&rdot=1

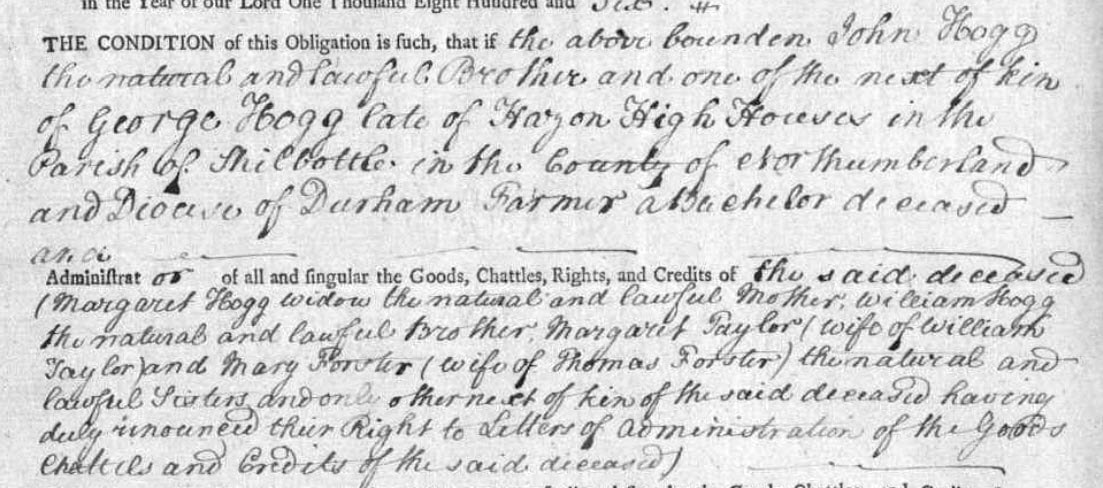

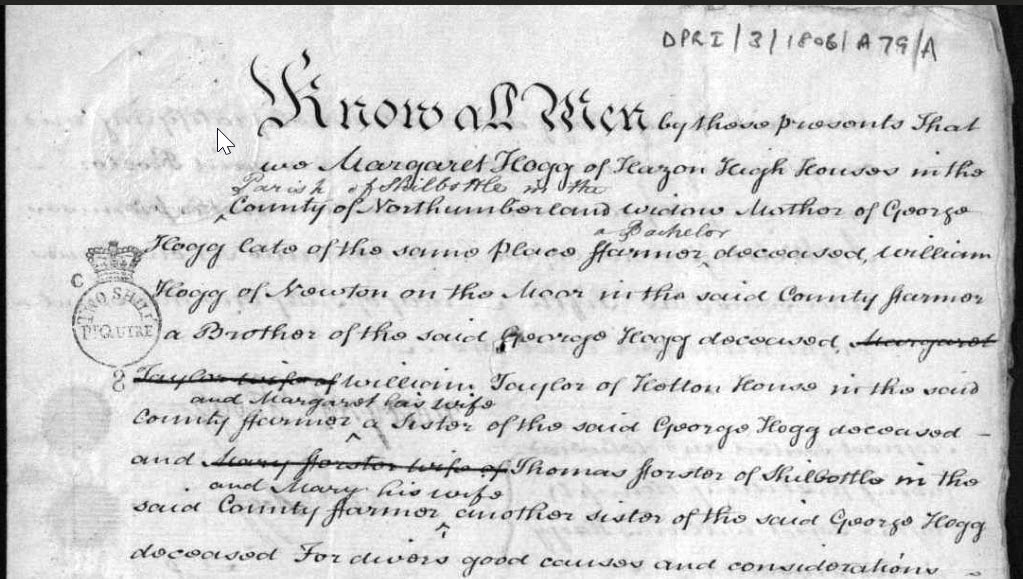

[2] Probate Admin of George Hogg of Hazon High Houses in 1806. North East Inheritance Database, England, Durham Probate Bonds, 1556-1858 DPRI/3/1806/A p.112

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HY-64VQ-XCS?i=110&cc=2353049

[3 & 4] Durham Records Online

https://www.durhamrecordsonline.com/

Useful Links

https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1309819

FreeReg

https://www.freereg.org.uk/

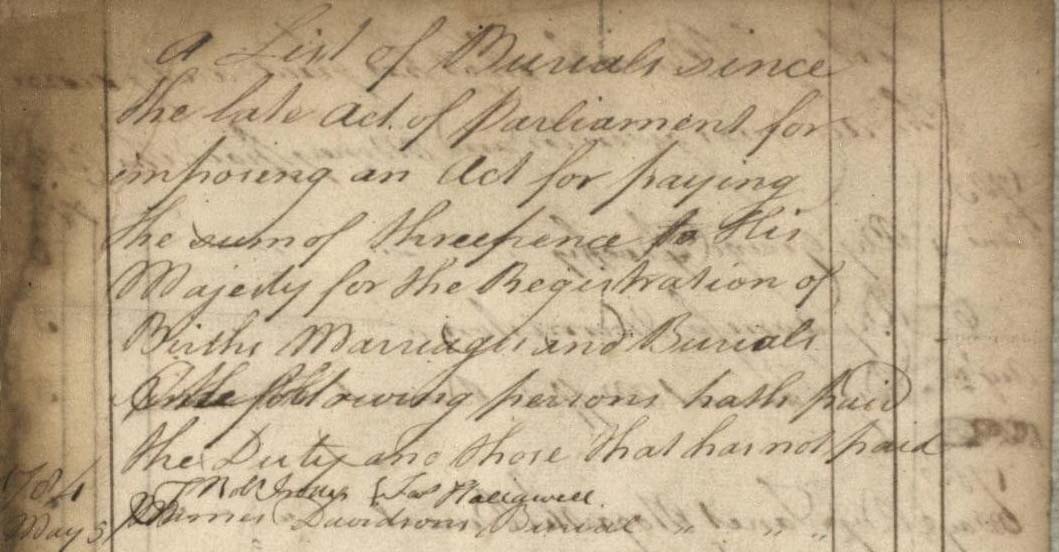

Debrett’s Ancestry Research Ltd, Bishop Shute Barrington and the English Parish Register

https://debrettancestryresearch.co.uk/bishop-shute-barrington-and-the-english-parish-register/

Durham University, North East Inheritance Database

http://familyrecords.dur.ac.uk/nei/

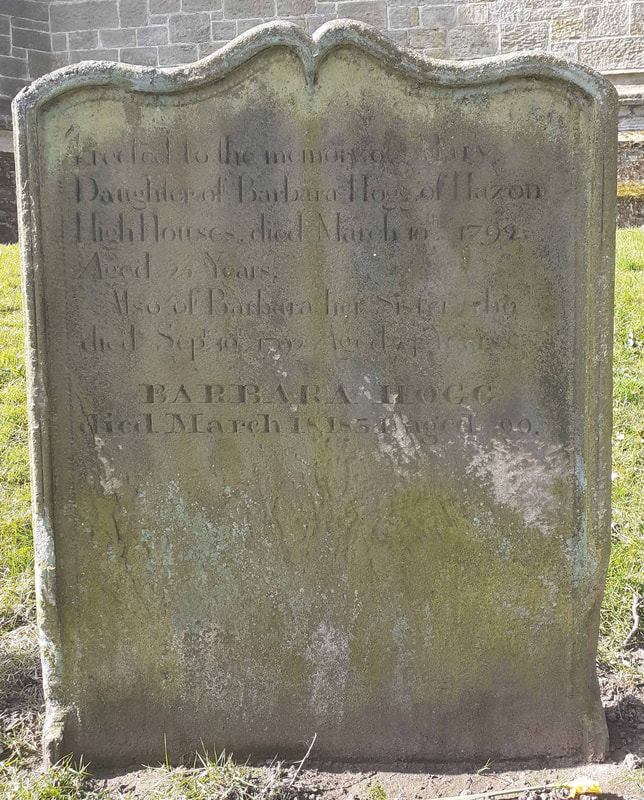

Transcription of Monumental Inscriptions at Shilbottle

https://www.fusilier.co.uk/shilbottle_northumberland/churchyard/monumental_inscriptions.htm

Background

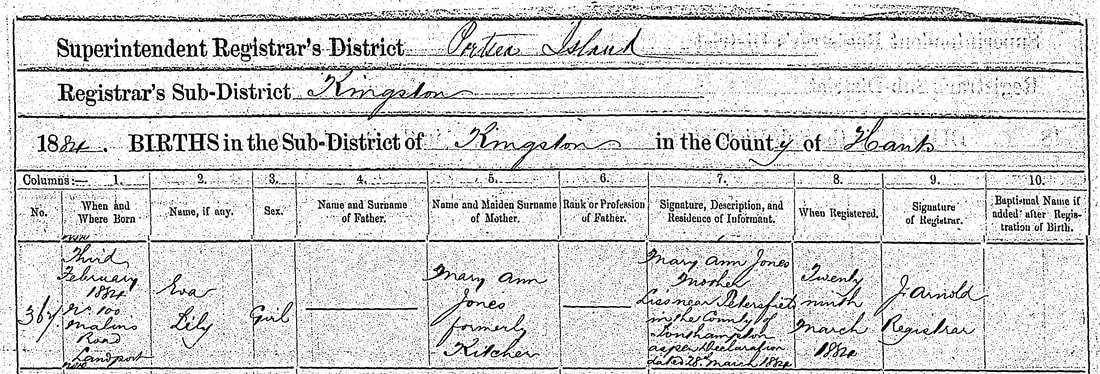

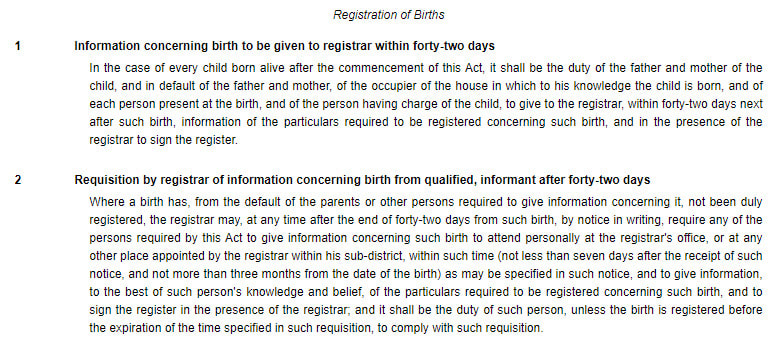

Births and Deaths Registration Act 1874

Mary Anne Kitcher

Kitcher was a servant at Stone Farm, Exbury and on the 27th December, in 1867, met Rowe, a Master Mariner, at his father's house at Lepe, and he accompanied her and her brother part of the way home. She saw him again in February and on the third time of their walking together, Sunday, the 1st of March, they had intercourse during the afternoon, resulting in November in the birth of a child, to maintain which she summoned Rowe before the magistrates, but they dismissed the complaint.

Rowe thereupon went to the Nelson Inn and glorified his victory by 'standing' two gallons of beer for the delectation of the assembled company, to whom, in the course of his glorification, he made sundry boastings as to his manly qualities, and that the child was his. This coming to Kitcher's ears she summoned him again before the magistrates, who then made the order now appealed against. Kitcher was now called and deposed to having met defendant on the three occasions above named. The last two times was on the shore at Stone Point, in the neighbourhood of his residence.

She added that she wrote to him informing him of her state, and in July saw him and asked him if he was going to support the child, and he said certainly not, and as to her letter it had nothing at all to do with him. She had not seen him since. In cross-examination she said she had only intimacy with him on the Sunday in March – not at the February meeting, which was also on Sunday. A letter was then put into her hand, and she admitted having written it. The Clerk read it, as follows:-

"Dear Tom – I am very sorry I am obliged to tell you I am in the ______ . It is by you. So, I have written to tell you I have left, for I was not able to do my work. So, I am staying at home now with my father and mother. So, I want to know what to do. So, I hope you'll write and tell me what you intend to do ….. So, I hope you will write to me, or my father will come to see your mother. It is no use to blame anyone else for it. I don't care what you say about it, for it is by you and no-one else. I was told that you should say 'let her try it on' but you know it was you as well as I do. It was on the Sunday I was on the Shore with you in February. So, I hope you will write and tell me what you intend doing. Good-bye dear. From yours truly Mary Kitcher."

She was cross-examined at some length as to her acquaintance and connection with others, the latter of which she positively denied…

The case for the defence was that the appellant did not deny intimacy with Kitcher, but that it was on the Sunday in March named by her, and that, coupled with other circumstances, to be proved by witnesses, rendered it impossible for the child to be his.

The appellant having given his testimony, James Cotton, a labourer, living in the neighbourhood , deposed that in the month of February he was on the way to see his sweetheart and met Kitcher, who told him he would not get there; he had better turn back and go with her. He accordingly turned back and did as she suggested, near the Floating Island.

It was on a Sunday, and she was going to church she said. Afterwards he saw her again and she told him her position and said he need not fear; she should not swear to him but to Tom Rowe because he had the most money.

David Mintrim, another labourer at Stone Farm, deposed to having met Kitcher in the brewhouse on the 24th February 1868 and gave details of what took place which, however, in cross-examination, Kitcher after giving her evidence, most positively denied – indeed she denied all knowledge of any other that Rowe, though the names of the witnesses called were put to her.

Mr Russell, cross-examining Mintrim asked him details of the 'many' times to which he referred and he said twice before the 24th February, but never afterwards. She asked him – Mr Russell: And didn't you make a note in your pocketbook of such an extraordinary request? Witness: 'Naw. I never carries a pocketbook. He is and was at the time a married man. On the 24th February she told him she should make Tom Rowe pay, as he has the mostest money.

Henry Brown, a shipmate of the appellant's, gave evidence as to intimacy in December and February with Kitcher with whom he had walked fifty times. (She swore she had seen him only three times) Emily Mintrim, wife of the previous witness said that she saw Kitcher at her place of service in April and she told her her condition, and she should swear to the one that had the moistest money, Thomas Rowe.

Postscript

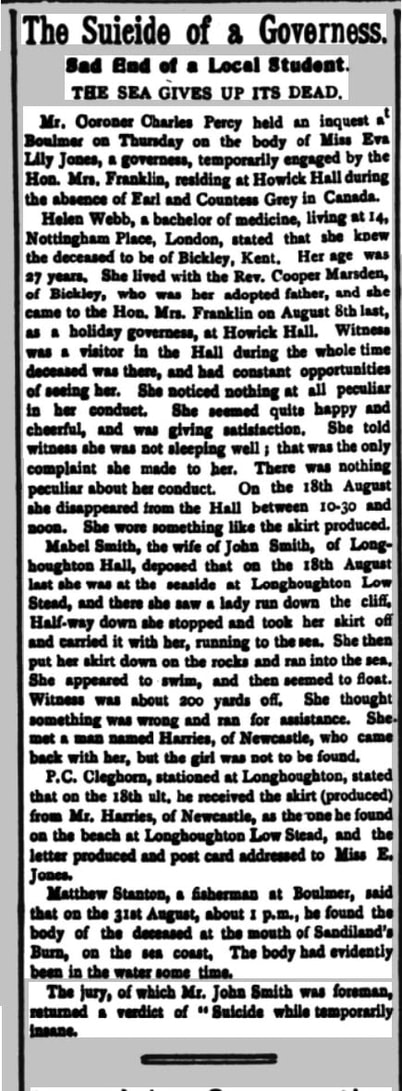

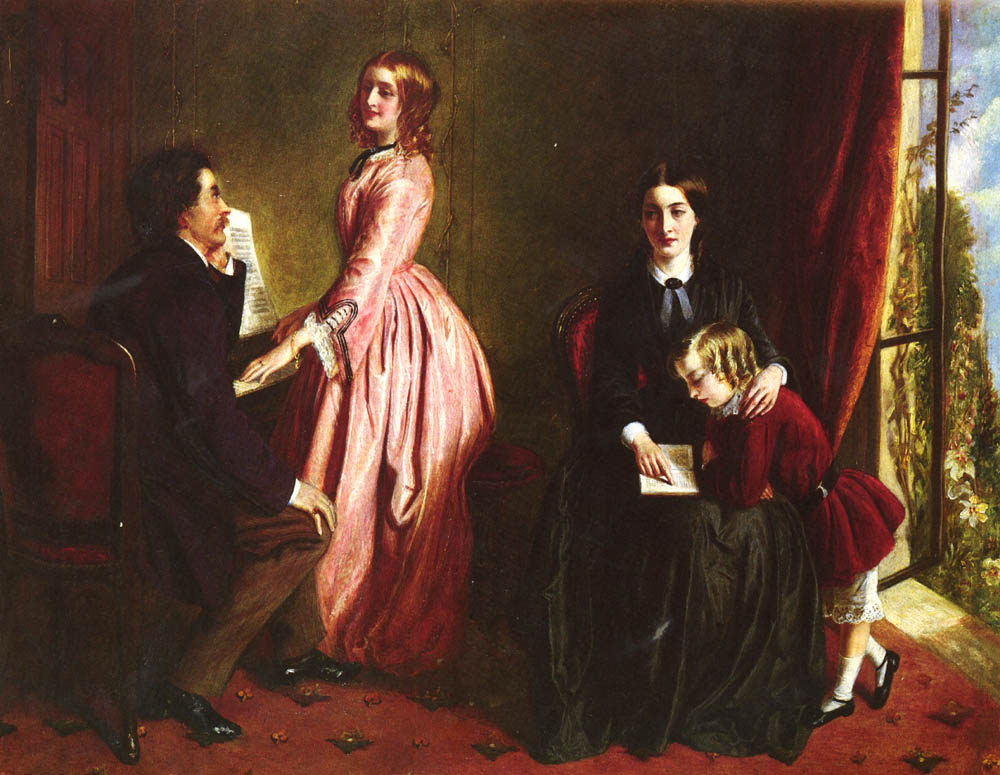

Being illegitimate and from a working-class background would almost certainly have precluded Eva from the position of Governess. Nor would it have provided her with the requisite level of education and ladylike 'refinements'. Why then was Eva singled out and apparently 'groomed' for employment befitting a young 'lady'?

As well as the illegitimate half-sister born in 1868, Eva also had a half-brother Hubert Henry born to Mary Anne Kitcher and husband Anthony Jones in 1880. The couple married in the September quarter of 1878, but Anthony was already absent by the time of the 1881 census. Siblings Hubert Henry and Mary Jane remained with, or near to their mother and the Kitcher family. But Eva did not, her life was vastly different.

Neither Eva nor her mother fit the profile expected at the outset of research which serves to make it even more compelling. Was Mary Kitcher a 'schemer' and the Vixen portrayed or was she, like her daughter a victim of circumstance? With Eva apparently separated from her mother at an early age suggesting third party intervention other than the 'state', the question is by whom and why?

Their story continues to evolve …

[2] British Library, Kathryn Hughes, ‘The Figure of the Governess’,

https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-figure-of-the-governess

Further Reading

Kathryn Hughes, 'The Victorian Governess' London, 1993.

(There is 30% saving to be had buying direct through publishers Bloomsbury

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/victorian-governess-9781852853259/)

More information on The Hon. Henrietta Franklin C.B.E.

Snippets of information can readily be found online, including the website 'The Dinner Puzzle'. The site is based around the ‘guest list for a dinner held on 23rd March 1933 at which friends and colleagues assembled to present a portrait by artist Alice Mary Burton to Lady Rhondda – suffragette, businesswoman and publisher.’ A fascinating and different take on prominent women of the day.

https://thedinnerpuzzle.com/portfolio/the-hon-mrs-franklin/

Monk Gibbon, 'Netta', London 1960. A biography of Henrietta Franklin C.B.E.

The Forgotten Heroes of Family History - discover why business records make brilliant sources!

25/1/2022

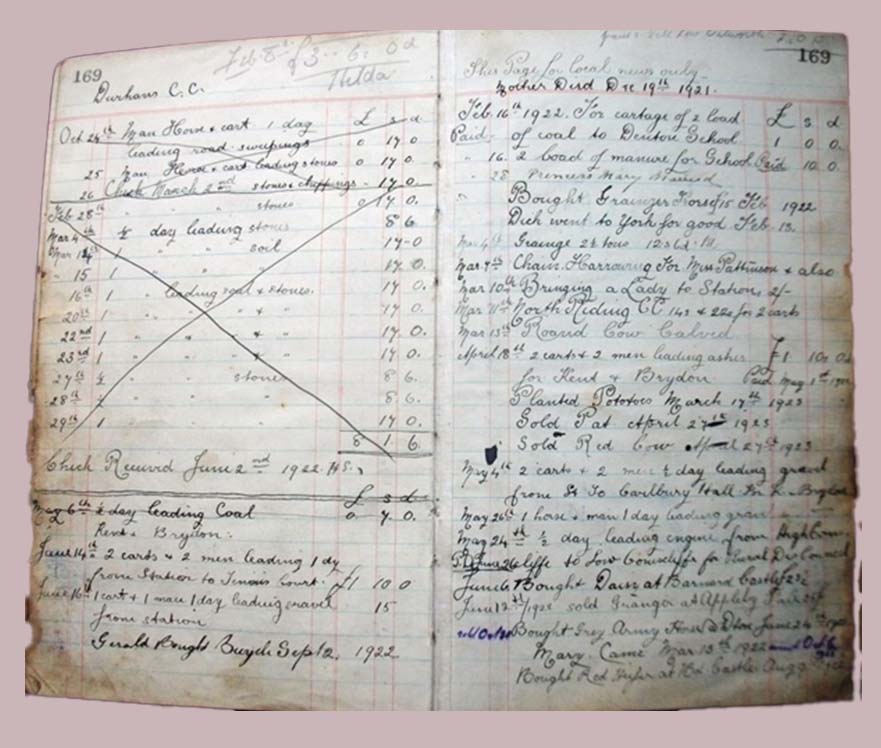

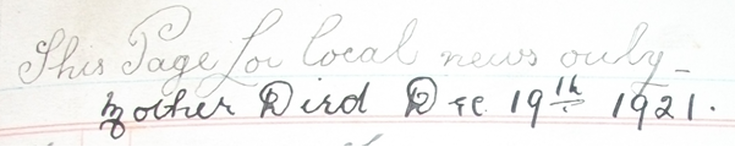

“Mother Died Dec 19th 1921.”

Today, in my minds-eye I can see him sitting at his desk, pencil in hand and licking the point of the lead before writing an entry. The picture below is of the last pages in this ledger, entitled ‘This Page for local news only.’

- 2 load manure for school

- Bought Grainger horse £15

- Roand cow calved.

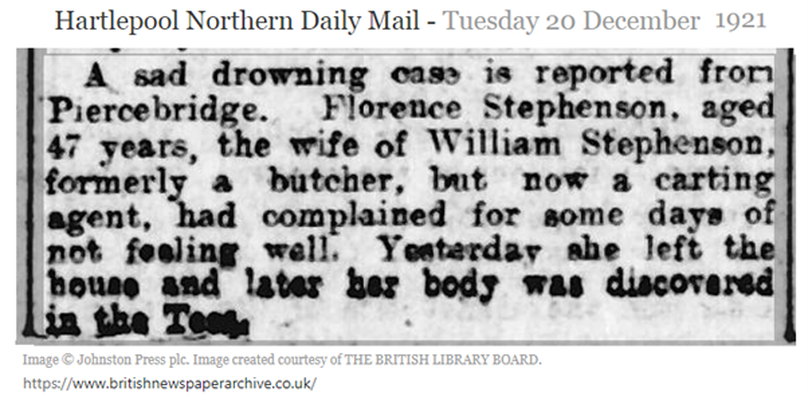

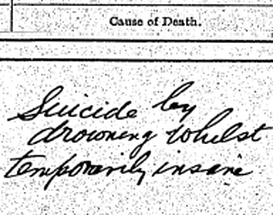

| It appears Florence had been feeling unwell for a few days when she left the family home in Piercebridge and 'later her body was discovered in the Tees'. Florence had drowned. Her Death Certificate was illuminating:- So perhaps my Grandfather was in shock or denial, or just grief-stricken when he wrote the words “Mother died” in the Ledger here before me. |

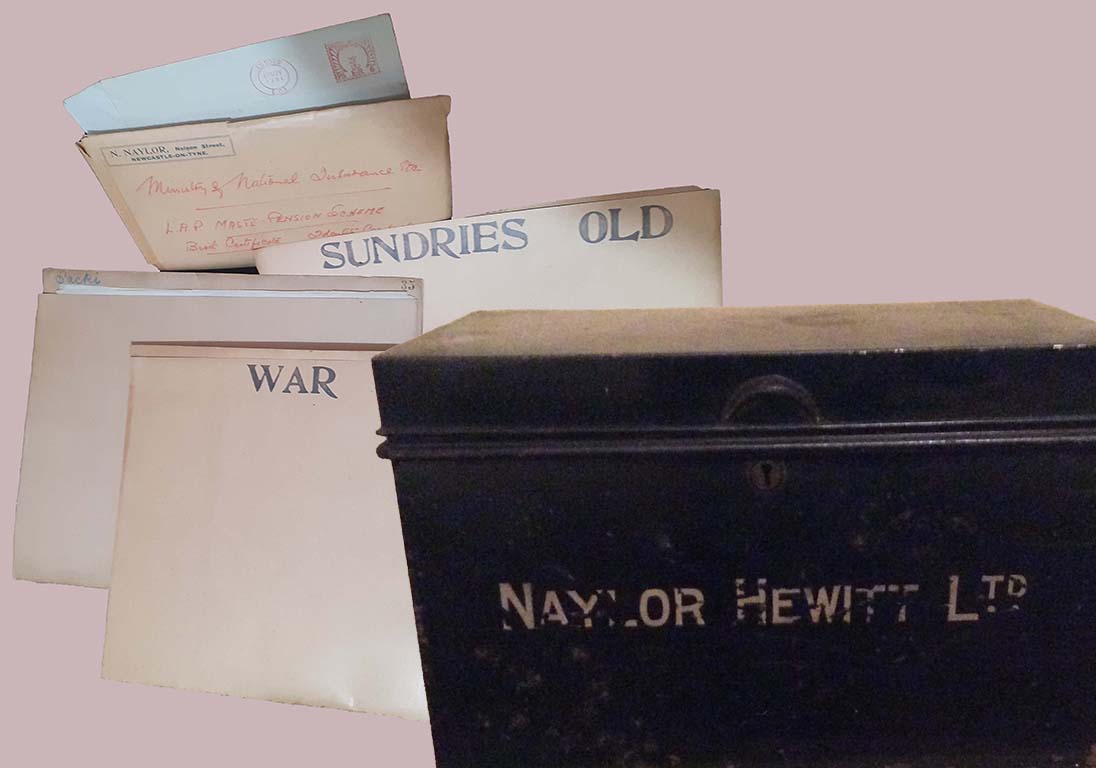

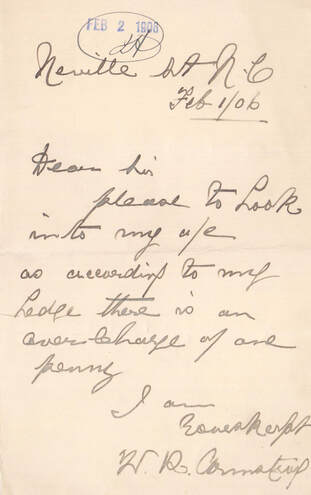

'Personals' in Business Records

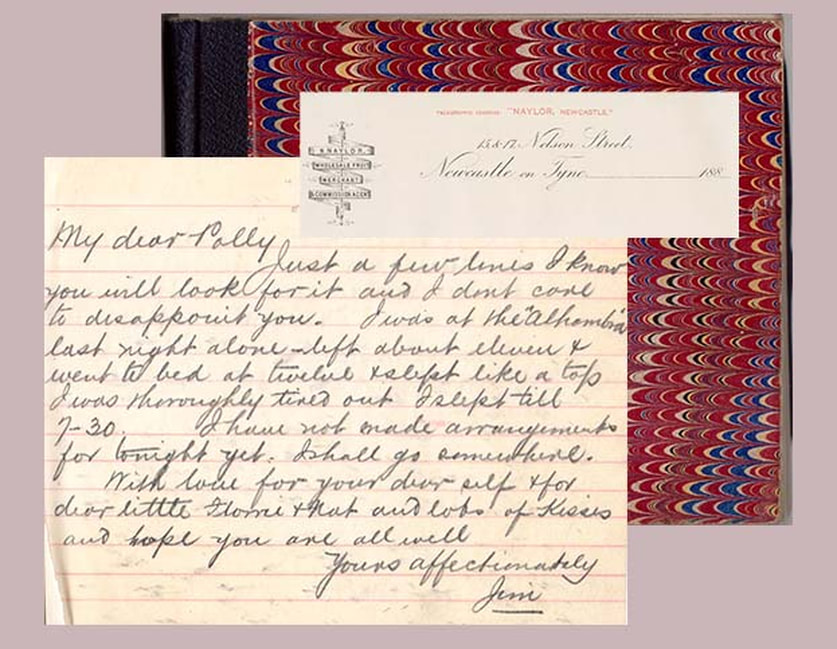

When it opened in 1854 The Alhambra Theatre hosted one of the few bars to accept women without the escort of a man. Once described as the “greatest place of infamy in all London”, it had a reputation for banging nights out.

The leading ladies of the stage would descend underground after their performance, declaring, “Come, won’t you bring me my liquor?”. They would flirt, eat oysters, drink champagne and make eligible acquaintances.

Lost in a fire in 1882, the site was rebuilt but said to be cursed by housing such debauchery and eventually demolished in 1936 to become the Odeon Theatre.[1]

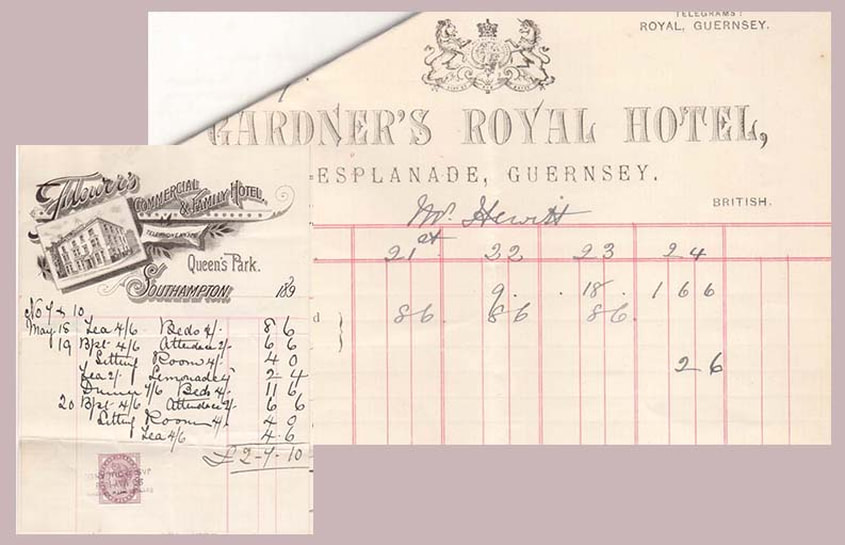

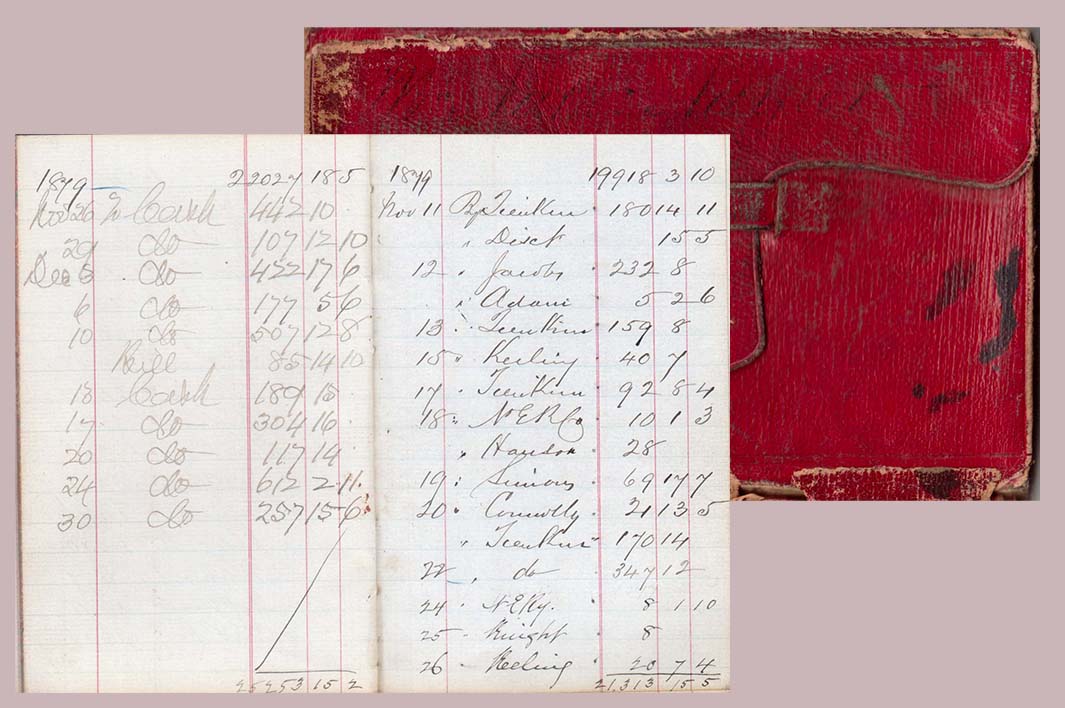

Purchase ledger for November 1877. Private Collection

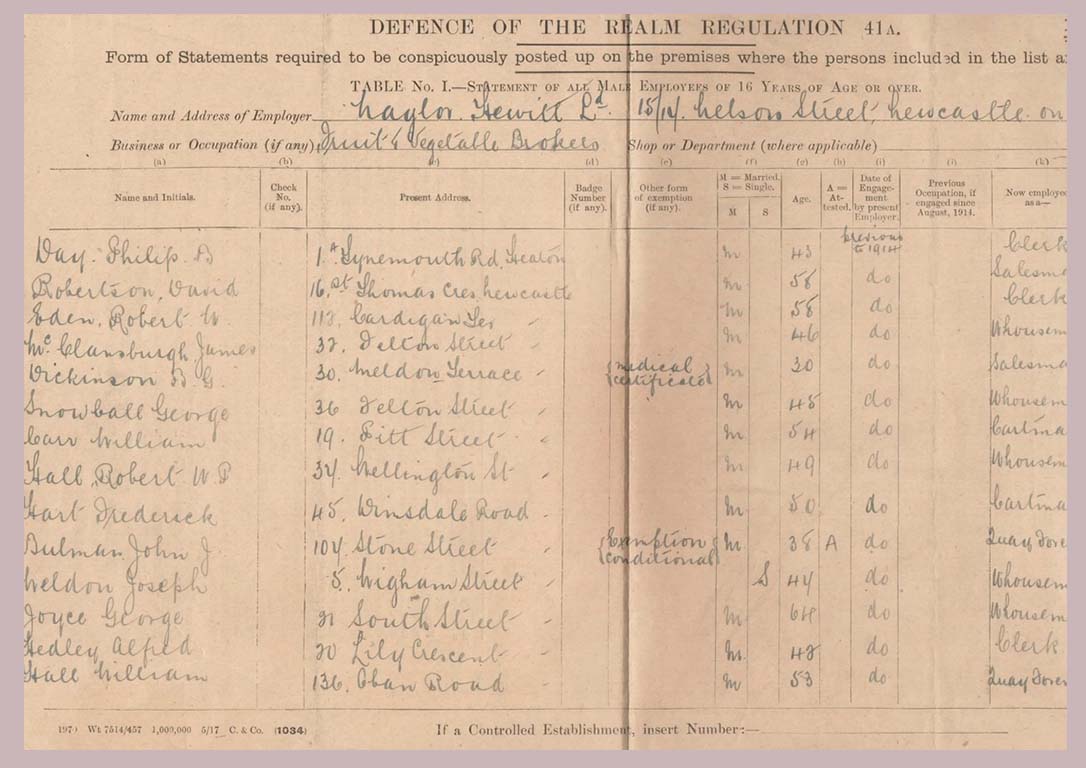

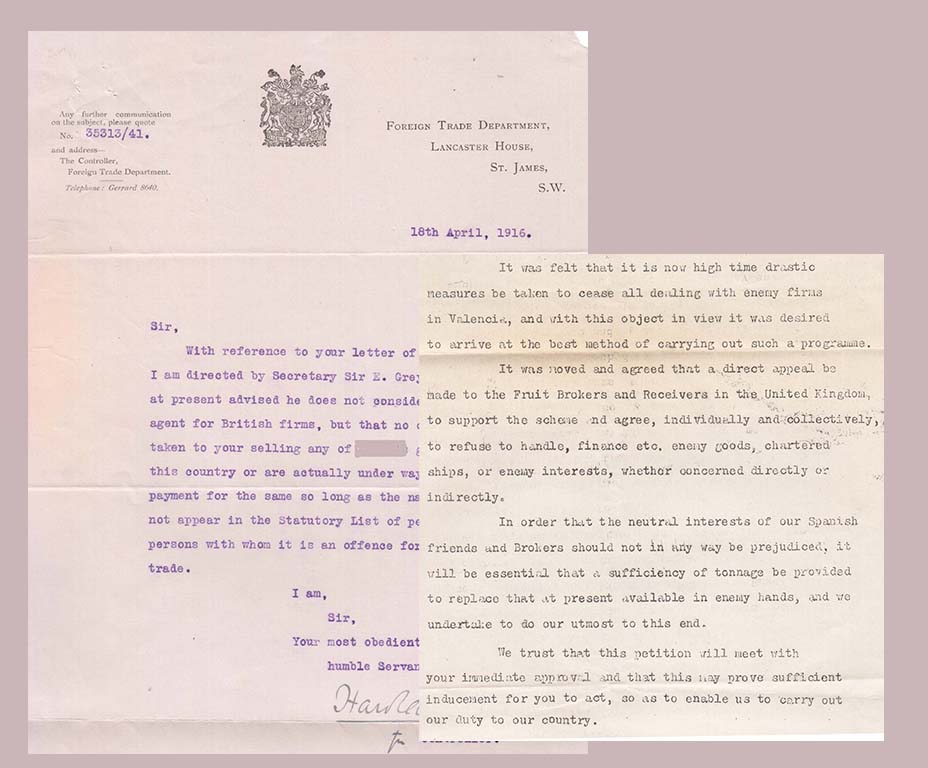

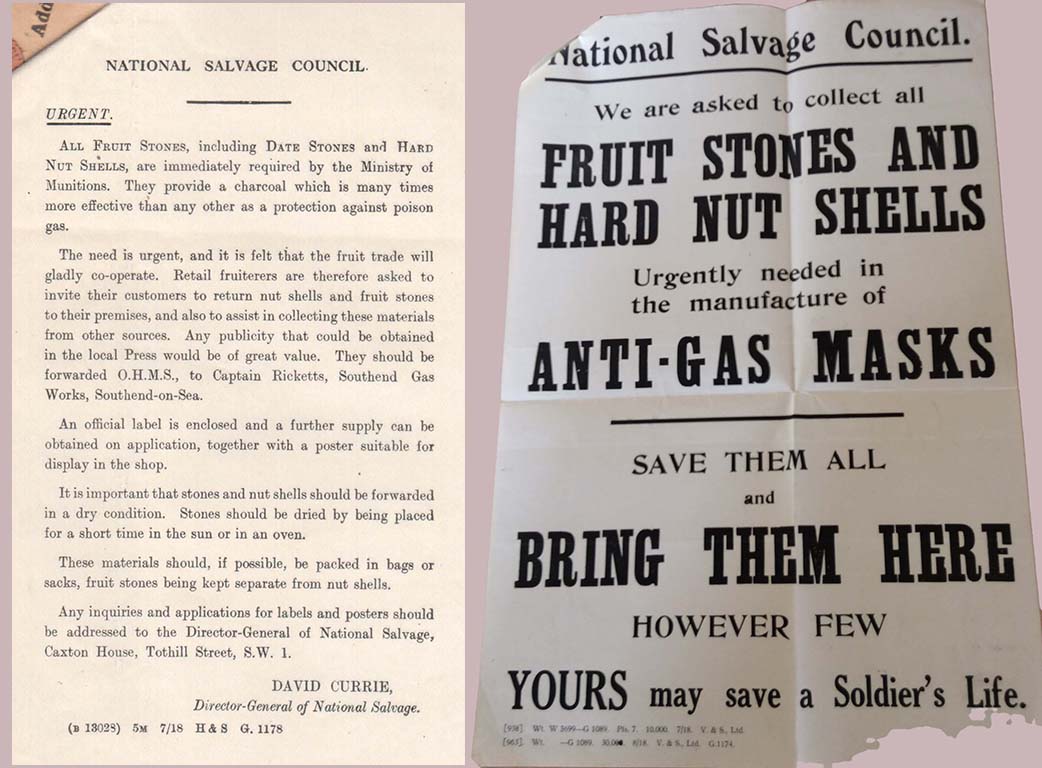

Purchase ledger for November 1877. Private Collection World War I

The history of buildings and places

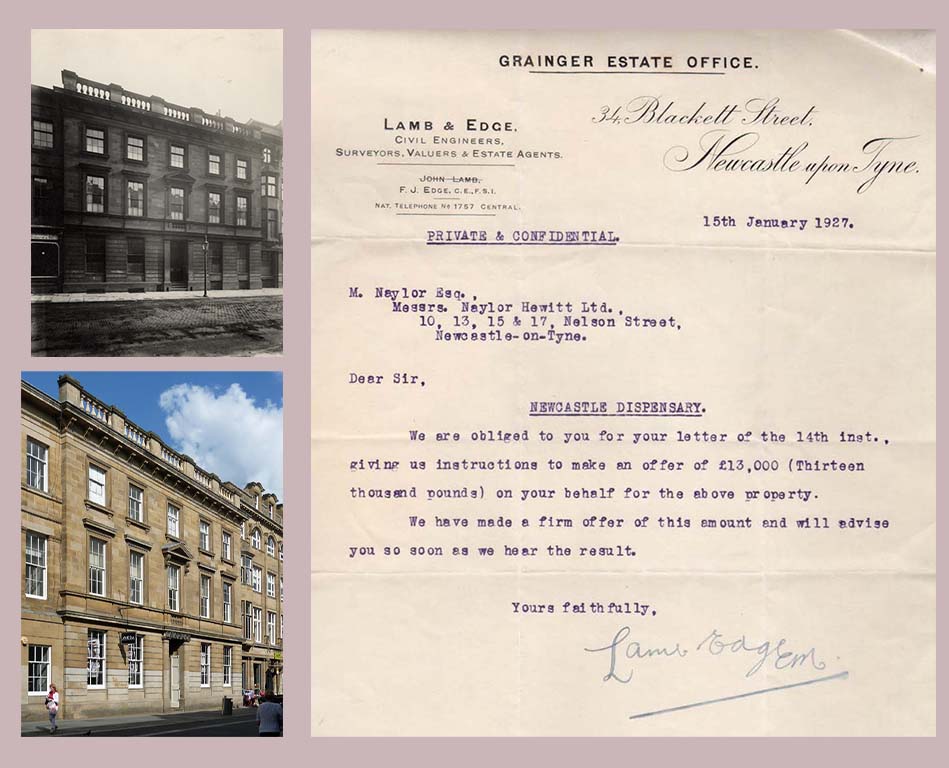

The Dispensary, 14 Nelson Street, Newcastle-upon-Tyne

The Dispensary was established in April 1777 and funded through subscriptions, gifts and legacies. Its first site was in The Side but in 1782 or 1783 it moved to Pilgrim Street where it remained until 1790. For the next fifty years, the Trustees leased a building in Low Friar Chare. At the expiry of the lease, the Dispensary moved to 14 Nelson Street, where it remained until 1928. Its final move was to 115 New Bridge Street which was still its home when it finally closed in 1976.[2]

The Fruit Exchange, Spitalfields, London

Opening in 1929, when the volume of imported produce coming through the docks more than doubled in the ten years after the First World War, the mighty Fruit & Wool Exchange in Spitalfields was created to maintain London’s pre-eminence as a global distribution centre. The classical stone facade, closely resembling the design of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Christ Church nearby, established it as a temple dedicated to fresh produce as fruits that were once unfamiliar, and fruits that were out of season, became available for the first time to the British people.[3]

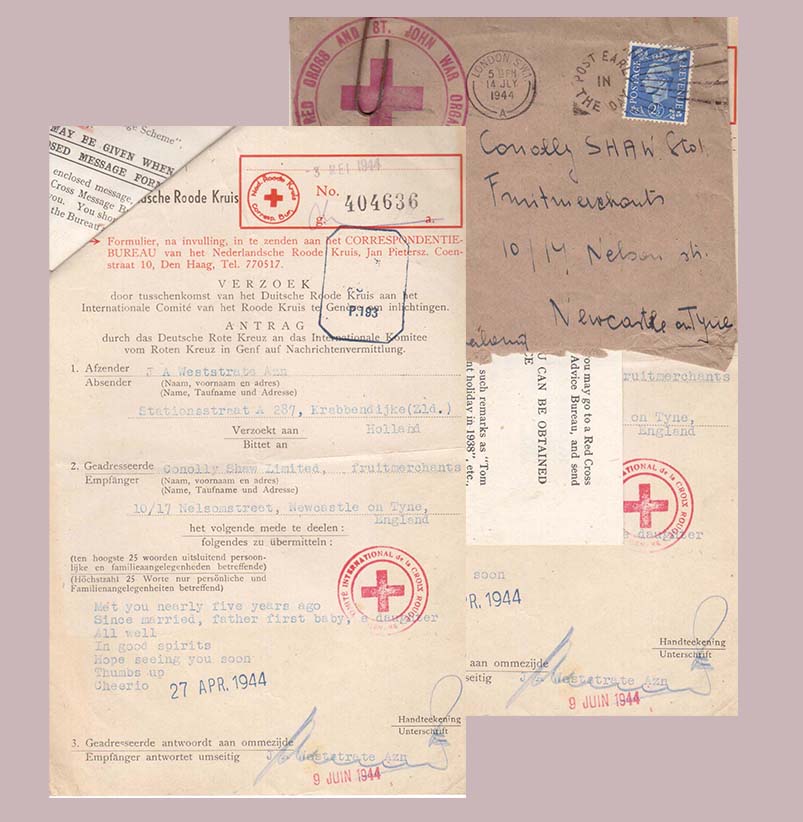

Another World War

A wee bit of fun to end

Footnotes

https://www.thelostalhambra.co.uk/

[2] The National Archives Kew,

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/8e55bb34-bcea-498f-8a47-7f9644c682b1 (Tyne and Wear Archives catalogue is unavailable at the time of writing due to essential maintenance.)

[3] Spitalfields Life ‘So Long, Spitalfields Fruit & Wool Exchange’

https://spitalfieldslife.com/2012/10/11/so-long-spitalfields-fruit-wool-exchange/

Links to further information

The Alhambra

Theatres Trust Database, the Alhambra

ttps://database.theatrestrust.org.uk/resources/theatres/show/3263-alhambra-theatre-london

Cinema Treasures, The Alhambra

http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/30493

The Old Dispensary & Newcastle’s Grainger Town

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1024812?section=official-listing

English Heritage, Newcastle's Grainger Town An Urban Renaissance, London, 2003. (84 page pdf downloadable publication about the history of Grainger Town and recent conservation project.)

https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/newcastles-grainger-town/newcastles-grainger-town/

The London Fruit and Wool Exchange

https://spitalfieldslife.com/2020/01/11/at-the-fruit-wool-exchange-1937-x/ (Some wonderful articles on this website!)

Religious Reform in Seventeenth Century England

…witnessed the trial and execution of a king, the formation of a republic in England, a theocracy in Scotland and the subjugation of Ireland. [1]

… encouraging subjects to treat the mid-winter period 'with the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance our sins, and the sins of our forefathers, who have turned this feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights'.[2]

The origins of Christmas stretch back thousands of years to prehistoric celebrations around the midwinter solstice. And many of the traditions we cherish today have been shaped by centuries of changing beliefs, politics, technology, taste and commerce.[3]

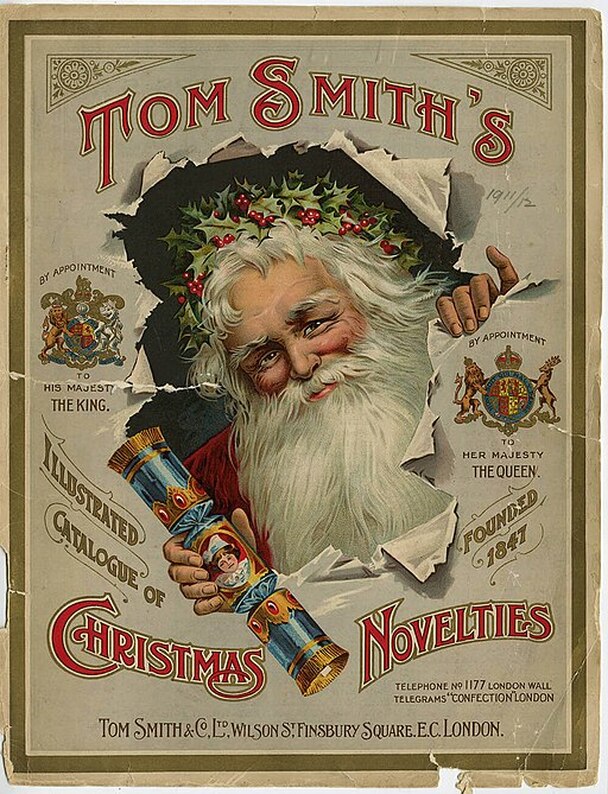

'Lord of Misrule' & the Christmas Cracker

The Scottish Ban on Christmas

In the Christmas of either 1563 or 1564, Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1561-1567) held a ball at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, where she and her guests celebrated the ‘Feast of the Bean’. The ritual began at the start of the Christmas period and involved hiding a bean in a cake: the person to find it would be crowned ‘King/Queen of the Bean’. In this year, Mary Fleming, who was one of the Queen’s ladies, found the bean and was dressed in the Queen’s clothes as a prize.[4]

In 1575 the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland abolished ‘all days that hereto have been kept holy except the Sabbath day, such as Yule day, saints’ days and such others’. Nevertheless, Scots continued to celebrate Hogmanay. Changes in church government meant that in 1640 and again in 1690 Parliament abolished the ‘Yule Vacance’ observed by the courts. The 1640 Act stated:

“….the Kirk within this kingdom is now purged of all superstitious observations of dates…thairfor the Saudis estates have discharged and simply dischairges the foirsaid Yule vacance and all observation thairof in tymecoming”

TRANSLATION

“…the Kirk within this kingdom is now purged of all superstitious observation of days…therefore the said estates have discharged and simply discharge the foresaid Yule vacation and all observation thereof in time coming”[5]

Link to

Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 (www.rps.ac.uk)

Reforms Repealed

Further Reading

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/christmas-is-cancelled/

The National Archives: Women and the English Civil Wars, How did these conflicts affect their lives?

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/women-english-civil-wars/

The BCW Project, British Civil Wars, Commonwealth & Protectorate 1638 – 1660

http://bcw-project.org/

BBC History,

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/

BBC History, (Extracts from the diary of Samuel Pepys explained)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/civil_war_revolution/pepys_gallery.shtml

An Instance of the Fingerpost (Readers Guide Only)

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/348324/an-instance-of-the-fingerpost-by-iain-pears/9781573227957/readers-guide/

End Notes

[2] Historic England, Did Oliver Cromwell really ban Christmas?

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/what-is-designation/heritage-highlights/did-oliver-cromwell-really-ban-christmas/

[3] English Heritage takes a tour of ‘Christmas’ through the ages starting 5000 years ago with the Neolithic

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/christmas/the-history-of-christmas/

[4] Christmas at the Palace of Holyroodhouse

https://www.royal.uk/christmas-palace-holyroodhouse

[5] National Records of Scotland, Christmas Banned in Scotland

https://blog.nrscotland.gov.uk/2018/12/10/christmas-banned-in-scotland/

The Trotter Family of Sprouston - Errors online & busting tricky inter-family relationships.

24/11/2021

Part One

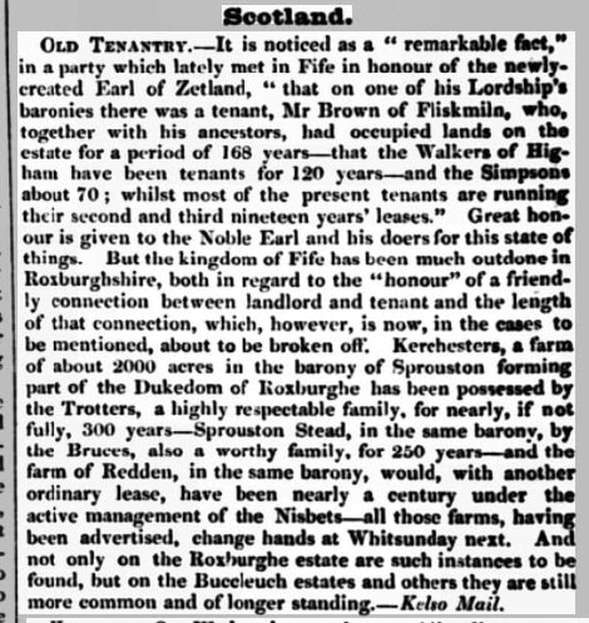

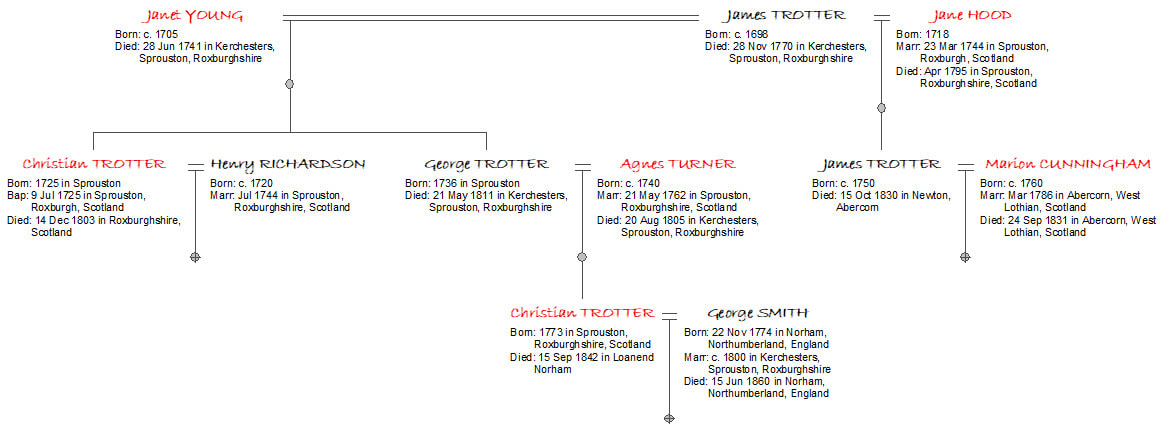

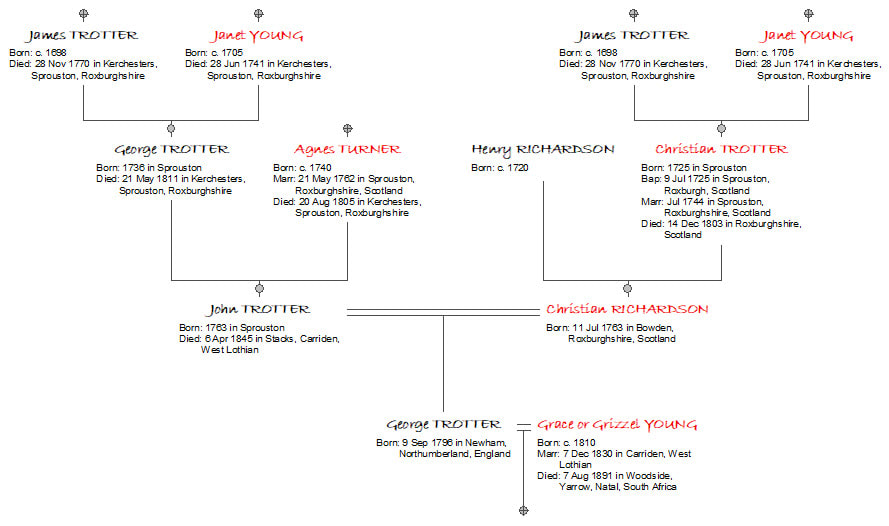

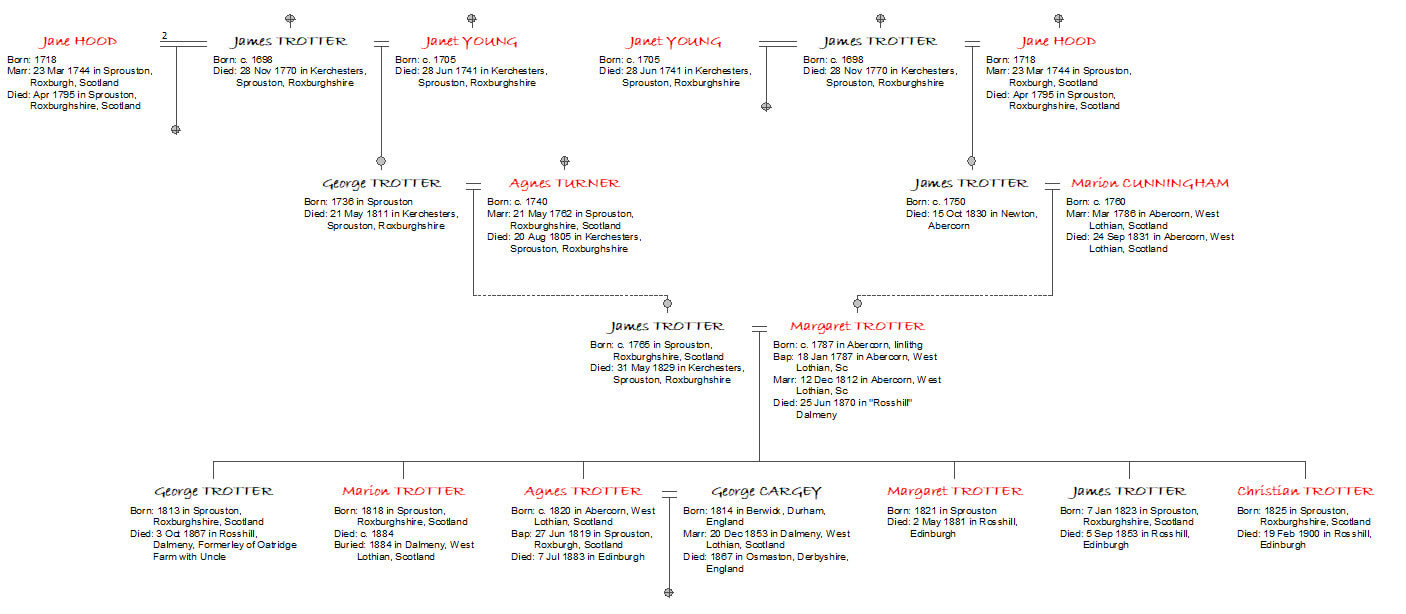

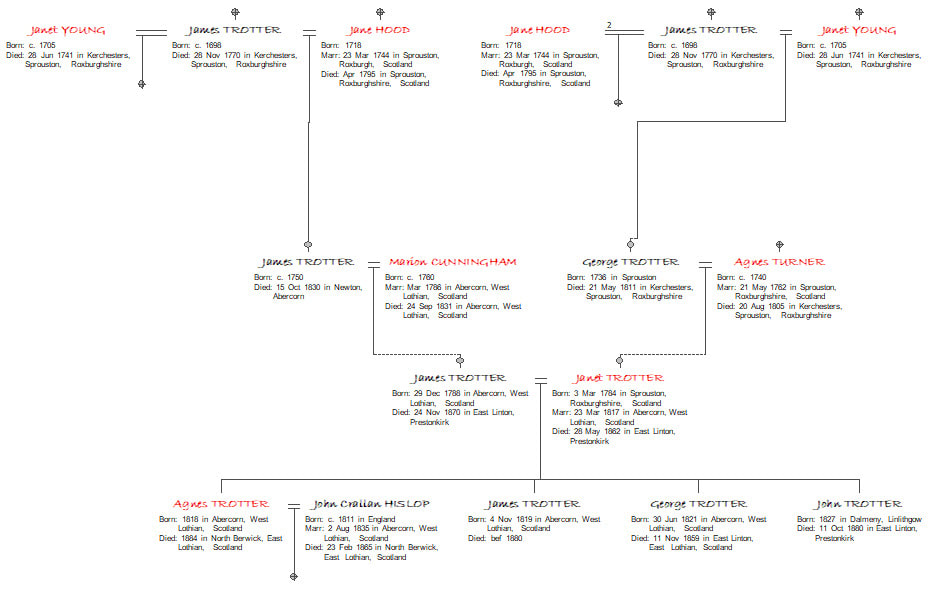

| A 'Reynolds' the portrait certainly is not but as a piece of family memorabilia it is equally as precious. (Although I fear he may scare small children ...) In later life, George had problems with his eyes, purchased his meat by length rather than weight, and banged his walking stick on the floor when his grandchildren made too much noise or as a signal it was time for them to leave. His imminent return reminds me that I still have not set the 'records' straight regarding his wife's family, the Trotters of Kerchesters Farm, Sprouston. Many members of this extended family appear incorrectly in online family trees. It is not surprising given the numerous cousin marriages and unions between inter-connected families. The complex connections are further confused as various children settled away from Borders. As they spread their wings their respective enterprises, farming and otherwise, covered a wide geographical area, with pockets in West Lothian, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St Andrews and beyond. |

Errors in public online trees.

Research Evidence

Trotters of Kerchesters

Christian Trotter 1773 - 1742

- born in Jedburgh in 1775

- the daughter of Alexander Trotter and Margaret Scougal

Alert – the remainder of this article carries a serious boredom warning – unless you are connected to the Trotter Family of Sprouston it may be of limited interest.

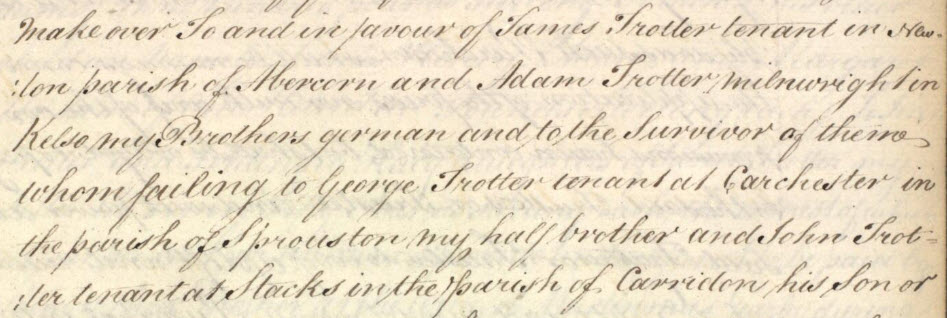

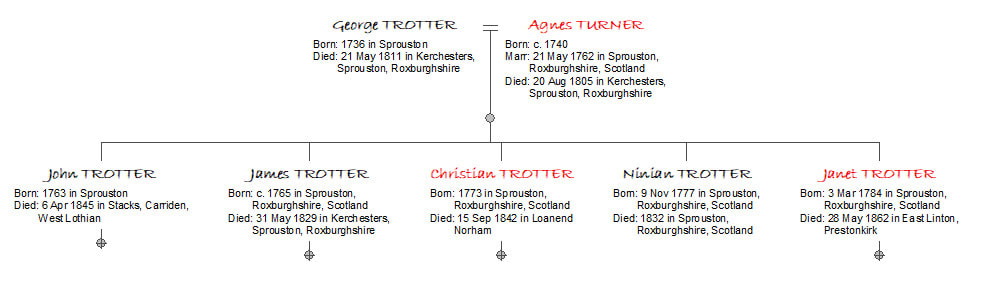

James Trotter of Kerchesters c.1698 – 1770.

Siblings of Christian Smith nee Trotter

John Trotter 1763 - 1845

He married his first cousin Christian Richardson, at date and place unknown. Christian Richardson was the daughter of Christian Trotter and her husband Henry Richardson. The couple's only child, George, was baptised at Warenford, Northumberland, by the Rev Mr Nichol in September 1796.

- was NOT married to Margaret Clarke

- was NOT married to Martha Pawnaby

- did NOT die at Melrose in 1809

- was NOT born in Carriden in 1801

- his mother was NOT Jean Whitly

- his father John was NOT born in Westruther

James Trotter 1765 - 1829

- 1st son George for the paternal grandfather

- 1st daughter Marion for maternal grandmother

- 2nd son James for maternal grandfather

- 2nd daughter Agnes for paternal grandmother

- Margaret was NOT married to William Trotter

- Their son John did NOT marry

- NB – the Find a Grave family interpretation is also incorrect in places.

Ninian Trotter 1777 - 1832

Janet Trotter 1784 - 1862

Janet also married a half first cousin, James Trotter, at Abercorn on the 23rd March 1817. James Trotter was another son of James Trotter and Marion Cunningham. He was brother to both John Trotter, farmer at Oatridge, and Margaret Trotter, wife of James Trotter of Kerchesters. He also farmed in West Lothian at Westfield, Newton, near Abercorn. By 1851 James had retired from farming, and he and Janet were living at East Linton, Prestonkirk, where Janet died on the 28th May 1862.

- She was NOT married to Robert Paton

- She was NOT married to James Tully

Conclusion

- If unsure a relationship is correct either mark it as such or don't add it to your online tree until the connection is verified.

- Keep your research trees private. This way no one can copy your information and the virus of potential misinformation remains contained.

https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//research/list-of-oprs/list-of-oprs-758-811.pdf

[2] There are two marriages in the Sprouston register for the marriage of George Trotter and Agnes Turner. The first was on 21st May 1762 and the second the 1st October 1773. They are believed to be the same people.

[3] Carriden Parish Burials Pre 1855, Central Scotland Family History Society, July 2004.

[4] James Trotter wrote on land improvement in West Lothian which appeared in The Scots Magazine - Tuesday 1st October 1811. Available as a free eBook from Google Books from page 767.

[5] Scotland's People, 1885 Trotter, Marion (Wills and testaments Reference SC41/53/14, Linlithgow Sheriff Court)

Author

Susie Douglas

Archives

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

October 2016

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

January 2016

December 2015

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

April 2015

March 2015

February 2015

January 2015

December 2014

November 2014

October 2014

September 2014

August 2014

July 2014

June 2014

May 2014

April 2014

March 2014

February 2014

January 2014

December 2013

November 2013

October 2013

September 2013

August 2013

July 2013

June 2013

May 2013

April 2013

March 2013

February 2013