|

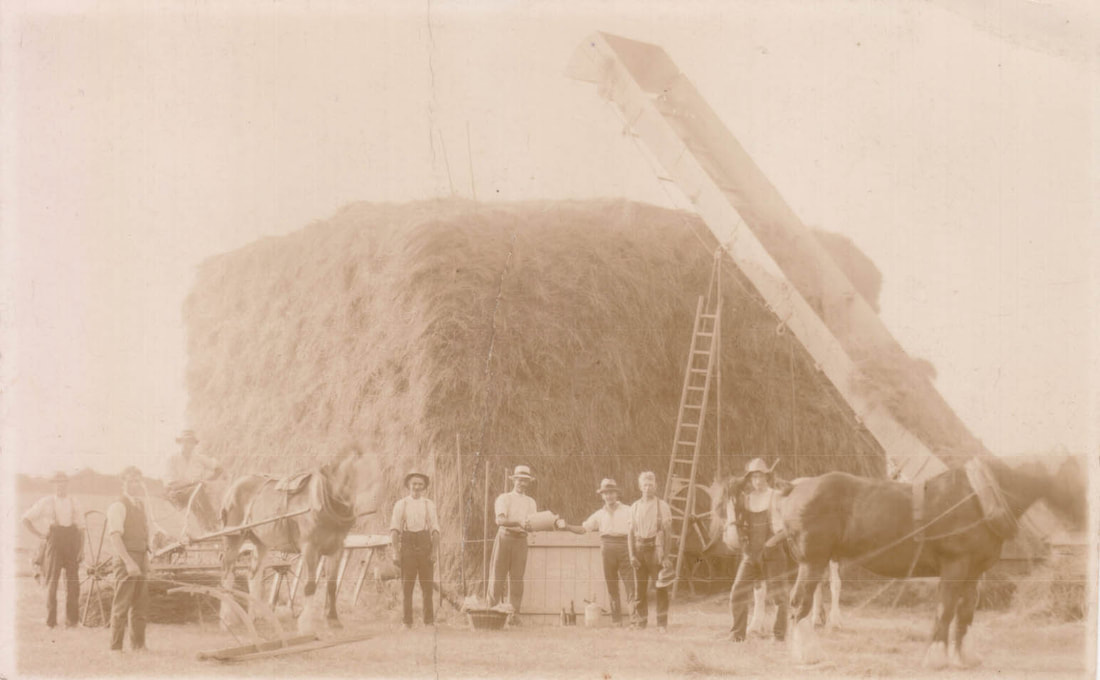

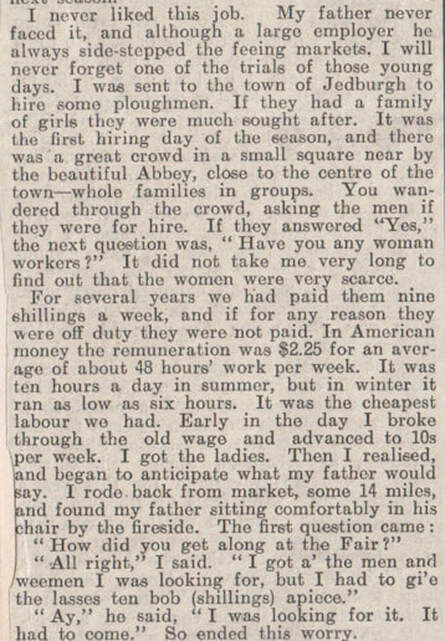

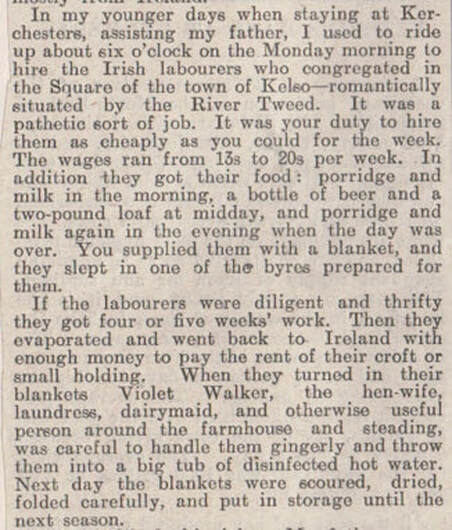

January 1 [1833] 'Here my friends, we are just entered again upon another New Year!!! Struggling against debts, taxes, tithes and feudal impositions, these are trying things.' The above extract dated 1st January 1833, is the opening line from the diary of William Brewis, a farmer of Throphill Hall Farm, Mitford. It covers 17 years from 1833 until his death in 1850. It reflects upon the concerns, economic and political of the time that faced farmers in rural Northumberland and beyond. There is much to learn about rural life of the period from diaries such as these which provide vital social commentary. And it was not all doom and gloom! There are family celebrations, fairs, festivals and other occasions of social and sporting events. William's political persuasion and his views on local, national and even international matters are never in doubt. Despite being his personal account, it is packed full of other people. He even had plenty to say about some of my own ancestors who happened to be his relatives too! This month's blog addresses a point raised amongst the fantastic feedback to 'Eight Easy Ways to create compelling Ancestral Life Stories'. Most ancestors will not have left diaries, letters, or had books written about them so how is it possible to learn more of their journeys? Voices from the past are everywhere, often hidden in plain sight. It's a case of knowing where to look and thinking 'outside the box'. They appear in books, old documents, newspapers, oral recordings, and in other people's diaries such as Williams. Farmers aside, a large percentage of the population was employed in agriculture as Hinds, Shepherds and Labourers. Huge numbers of people lived a transient life as they moved from farm to farm, often on an annual basis. Among the hinds* there are not many to be found who were born in the parish where they are at present employed; and very few are there who drew their first breath in the cottage which is now assigned to them, or even on the property which they enrich by the sweat of their brow. They are hired, for the most part, from year to year, on an agreement which binds them to their employer for twelve months, beginning and ending about Whitsuntide ... This provision of a female outworker as part of the Hind's 'Bond' or employment contract was peculiar to Northumberland, the eastern Scottish Borders and the Lothians. Author Dinah Iredale's guest blog of February 2014, provides an excellent overview of this practice. Her book 'Bondagers: The History of Women Farmworkers in Northumberland and South East Scotland' is an excellent source of information and references. Many of the quotations within this blog come from within its pages. Particularly the chapters covering Flitting, Hirings and workers' accommodation. The 'Flitting'Before the Flitting and Hiring, came the 'Speaking', where the farmer and hinds would discuss a potential extension of his contract for another year. The Hind was under no obligation to accept an offer and had the right to move and find another situation. 'Flitting Day' in Northumberland was the 12th May. (In the Scottish Borders and Lothians it was the 26th May which sometimes caused logistical issues.) Although referred to as 'The May' it bore no resemblance to festivities held elsewhere. Hastings Neville in 1909 recalls the scene as '… roads morning to evening thronged with carts piled high with the furniture and bedding of a large proportion of our population.' He further recalls ' the furniture in one cart piled to a dangerous height, with the grandfather clock lying lengthwise and risking its life on the top. In the second cart are the women and children seated on the bedding, caring for the caged canary and the cherished pelargonium which grew at the cottage window…'[2] There are mixed accounts over the 'flitting'. Some look back with affectionate nostalgia at what must have been quite an upheaval to undertake every year. 'Well, there were usually three carts. Oo got a' the furniture on the three carts. Usually, the third yin wis what they ca'ed a short cart, that was a sma' yin. And the mother usually went in the wi' the youngest bairns and the cat, if ye had yin, or the pig in a bag. It would lie squealin in the straw.' [3] Another lady recalls 'the cat would be the first thing to be 'packed' on flittin morning, in case it disappeared during the flurry'.[4] The 'flit' was so ingrained in some that even in old age they persisted with the annual move. One chap of 80 employed at East Bolton in 1910 when asked if he would stay replied, ' I've nivver been ony mair than a year in ony place an' I'm no 'gain tae begin in my old age.'[5] And another, on finally deciding to stay put, asked the farmer 'if he might have a couple of carts for a short time … Just to ta' take the furniture a bit doon the road.'[6] Others seem relieved to see the back of it. 'I'll tell you what I like best? Not having to flit every year. It was awful, thon flittin'. I remember driving a horse and cart through the square in Kelso with all the furniture and my mother up at the back.'[7] Older family members living with the next generation were also involved in the 'flit'. There are tales of 'Granny' passing away the previous night, but due to the shortage of time, being bundled in with the furniture to be dealt with on arrival at the other end! Very often the vacated cottage would receive its new occupants later the same day. Leaving the vacated cottage clean and tidy with coals and kindling ready for the incoming tenants to light a fire seems to have been an unwritten code. That was if the fire grate had not gone on the cart too, as was usual in earlier periods. HousingThere are many accounts of the accommodation provided for farmworkers, some foul and some fair. It is generally accepted that before the nineteenth-century reforms, the state of housing throughout Northumberland, the Scottish Borders and Lothians was generally poor. Some accounts dating from the twentieth century are not pretty reading either. W.S. Gilly D.D., Vicar of Norham (1831) and Canon of Durham drew attention to the poor conditions of labourers' cottages and campaigned for changes. He refers to the cottages as 'miserable hovels', where 'the walls look as if they will scarcely hold together' and 'the thatch yawning to admit wind and wet'. His book 'The Peasantry of the Border: An Appeal on Their Behalf' contains some useful background information. In 1805 George Culley and John Bailey noted in a report that they had seen some significant housing improvements. That '…those [buildings] erected of later years are better adapted to the various purposes wanted on extensive farms and improved cultivation…' . Whereas their predecessors were 'very shabby and ill-contrived.'[8] (Those built from the mid-eighteenth century onwards often followed the same pattern of my own home. A long row of stone cottages, (6), of two rooms roughly 5m x 4m with a single door and two windows. There was a separate row of buildings housing the pigsty and the 'netty'.) An interesting snippet on the state of a vacated cottage appears in Walter White's book 'Northumberland and the Border': 'See an empty cottage before the hind has brought in his lumbering box there's, chairs and table, before he has set up his grate in the empty fireplace, fitted his window to the empty hole in the wall and you will think it's not good enough to be a stable.'[9] And another quoted from a first-hand account: ‘… about ninety years ago when there were no ovens and no windows; when people shifted they had ti' take their windows and fireplaces with them. No, the houses weren't all alike, the windows were different sizes, and they had to be made right with boards and cow dung.'[10] Other commentators note that, 'in the poorest dwellings the division between man and beast was only a low wooden partition. It was reckoned to be beneficial to 'let the coo see the fire'.[11] This is no isolated comment as there are frequent references to man and beast sharing a roof with little to separate them. When trying to connect with ancestors, it is helpful to list the things they did NOT own or even have access to. By today's standards toilets and running water were non-existent. In the words of Jean Willis of Alnwick in the 1920s and 1930s, 'the water tap [standpipe] served seven families and was a good distance from the house…. The netty was outside and … the wooden seat had two holes, a high one and a low one for a child.' (I remember the old disused 'double seater' outside the farmhouse at Longhoughton, but don't recollect a difference in the height of the seat!) Jean continues, 'The one netty had to serve three families ( about 15 people). It was no use if you were in a hurry and someone else was in. There was no sink to wash your hands after.'[12] It was not all grey, grim and smelly, though, as when 'put to rights' it was possible to make the cottages into a surprisingly comfortable and colourful home. As noted by the Rev Gilly as he describes the dresser with its 'large blue dishes and plates, some of Staffordshire ware, and other of Delf, intermixed with old china or porcelain tea-pots, cups and saucers…' and a 'handsome clock in the tall case and a chest of drawers'. He also remarks that there are books in most households with family bible taking pride of place. All this once past the cow that greeted him immediately inside the door! Standards of accommodation mattered, and a Hind was not above asking his prospective employer 'What sort of cottages have you?' before accepting a position.[13] At the Hirings in the late-nineteenth early twentieth century, another man's view was, 'family came first' and that 'a good house was worth £1 a week in the wage.'[14] Memories of the 'Hirings'These were often large gatherings where workers would be well turned out, sometimes wearing an emblem of their trade, such as a tuft of wool, whipcord, or a sprig of hawthorn in their hats. In 1827, Alexander Somerville, hoping to be hired as a Carter, also put a piece of straw in his mouth to show he was looking for a position. The Hirings were criticised as demeaning for those looking for work. In 1913 the general secretary of the Scottish Farm Servants Union noted '…the farmers went through the men pretty much the same way as they did their cattle.' With another lady remarking that 'my old aunt was a bondager. She said they used to stand on the cobbles at Alnwick and the farmers used to look them up and down as if they were horses.[15] An extract from the recollections of John Clay of Kerchesters, Sprouston and later Chicago suggests that some farmers also found the Hirings, an uncomfortable experience. John even found hiring casual labour by the week distasteful As the Hirings were also an occasion for folk to gather, it was a boom time for irregular marriages and socialising. Others went for this entertainment such as two girls who went to the hirings 'for sport'. 'The girls go the hirings and like it. They wear their best clothes and their white veils and bonnets. They often look a lump better than the gentry, for they look fresher like.'[16] There was also the inevitable element of drunkenness and disorderly behaviour. In 1875 at the March Hirings at Alnwick, Thomas Waite employed by John Smith of Longhoughton became involved in a brawl in which a policeman lost his life. (Later found to have been due to a heart attack rather than the ensuing riot.) Looking deeper into the lives of agricultural ancestors makes for a fascinating study. Uprooting family and belongings, sometimes on an annual basis may sound unsettling by modern standards. But voices from the past often speak fondly of the event. The crowded cottage with little privacy, no 'facilities' and a cow in the back room is beyond the comprehension of today's demands of at least one toilet per resident backside. But the past often tells of a warmth, colour and family unity absent in the present. Far from lost or even unrecorded, numerous sources contain the voices of rural men and women from the past. It is perhaps a case of tuning the modern ear to the correct frequency so they can be heard. Footnotes[1] W. S Gilly D.D. 'The Peasantry of the Border: An Appeal on Their Behalf' 2nd Edition, London, 1842 https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/_/NexK1GL4XWAC?hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjUo-eX6efzAhUllIsKHUMUB1MQ7_IDegQIBxAD [2] Rev. Hastings M Neville, ‘A Corner in the North: Yesterday and Today with Border Folk’, 1909 [3] Ian MacDougall, Bondagers. Eight Scots Women Farm Workers, Tuckwell Press, 2000. Mary King b. 1905 describing a flitting circa 1916. Cited in Dinah Iredale 'Bondagers' [4] Barbara W Robertson, 'Family Life: Border Farm Workers in the Early Decades of the Twentieth Century', Scottish Life and Society. The Individual and Community Life, John Donald, Edinburgh, 2005. Cited in Dinah Iredale, 'Bondagers'. [5] Bolton Parish Description, Scottish Women's Rural Institute, 1974. Cited in Dinah Iredale's 'Bondagers' [6] Ellingham Women's Institute, Collectanea. Scraps of English Folklore, XI, 1904. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0015587X.1925.9718328 [7] The Scotsman, Wednesday 5 July 1978. Liz Taylor interview with Mary Rutherford formerly of Mellerstain. [8] John Bailey and George Culley, 'General View of the Agriculture of Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland.' 1805. Available through Google Books https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/General_View_of_the_Agriculture_of_the_C.html?id=A3ZbAAAAQAAJ&redir_esc=y [9] Walter White, Northumberland and the Border, London, 1859. Available through Archive.org. https://archive.org/details/northumberlanda00whitgoog/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater [10] Rosalie E Bosanquet, 'In the Troublesome Times' 1929. Second-hand copies are readily available to purchase online. [11] Ian and Kathleen Whyte, 'The Changing Scottish Landscape 1500 – 1800', 1991. Cited in Dinah Iredale 'The Bondagers'. [12] Dinah Iredale, ‘Bondagers: The History of Women Farmworkers in Northumberland and South East Scotland’ 2nd Edition, Berwick, 2011. p. 105. [13] Henley, 'Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture' Royal Commission on Labour, HMSO, 1867. [14] Minnie Bell, School of Scottish Studies, University of Edinburgh. Cited by Dinah Iredale. [15] Katrina Porteous, 'The Bonny Fisher Lad', People's History Series Ltd, 2004. May Douglas, cited in Dinah Iredale's 'Bondagers'. [16] Arthur Wilson Fox, 'The Agricultural Labourer: Report upon The Poor Law Union of Glendale' (Northumberland), Royal Commission on Labour, HMSO, 1893. Cited in Dinah Iredale’s, 'Bondagers' Other Useful LinksDinah Iredale, 'Farming History - The Forgotten Workers' https://www.facebook.com/TheBondagers/ Matthew and George Culley: Travel Journals and Letters, 1765 – 1798. Available in part through Google Books https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=PwZhQUO4KlgC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false David R Stead, ‘The mobility of English tenant farmers, c. 1700–1850’ https://bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/51n2a4.pdf John Grey of Dilston, Berwick, 1841. A View of the Past and Present State of Agriculture in Northumberland and Details of Experiments with Various Manures.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2kdiAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

1 Comment

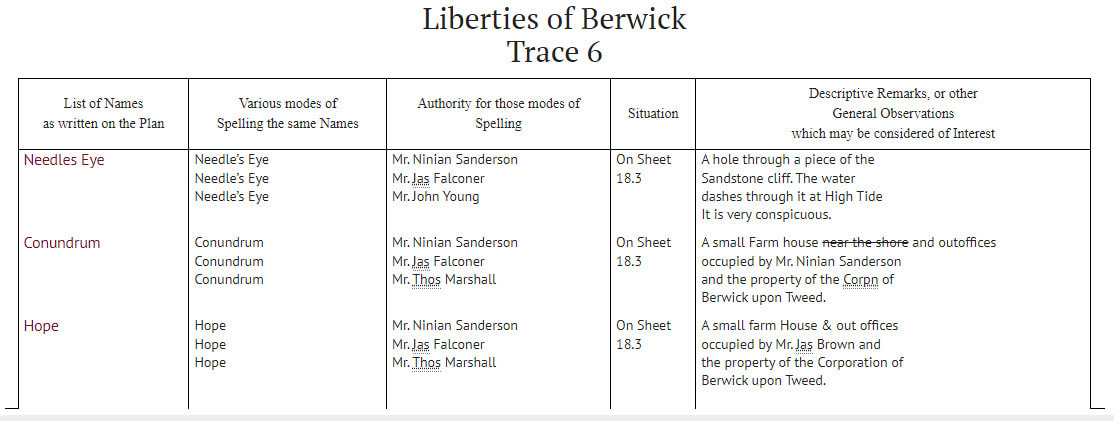

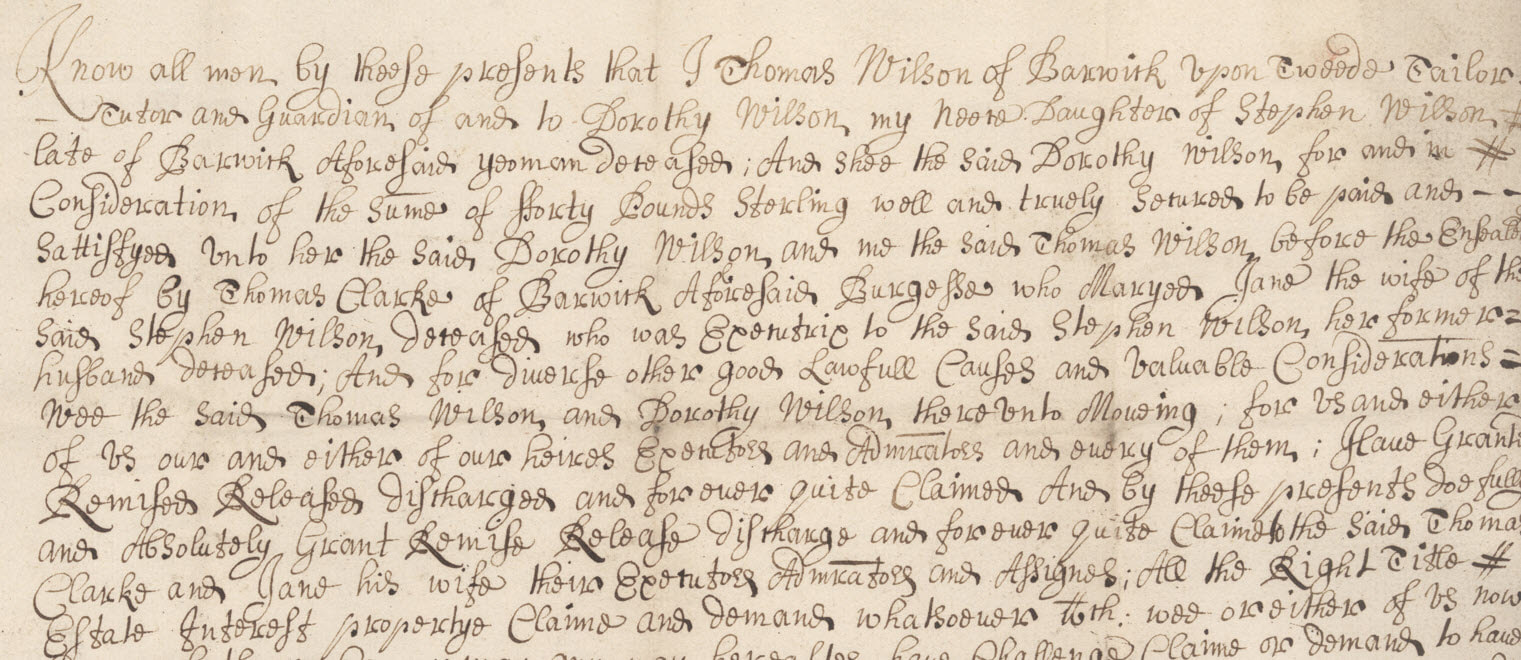

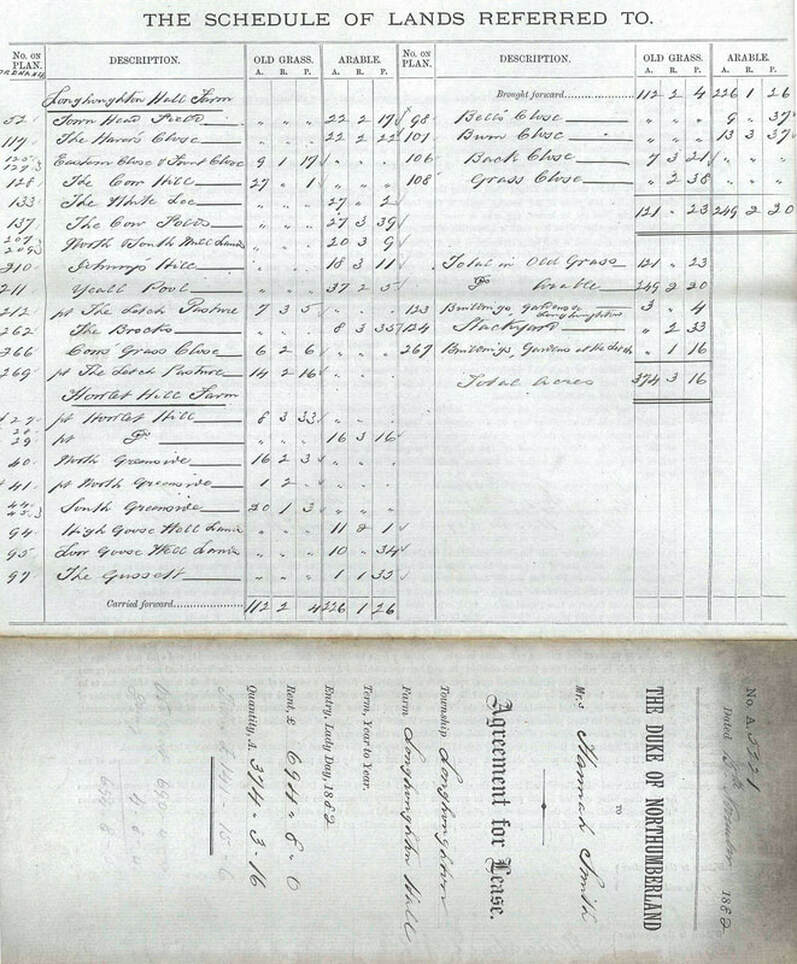

There is no better way to add context to family history than to research the homes, places and communities where ancestors lived. With the return of 'A House Through Time' for Series 4, there is a resurgence of interest in buildings associated with ancestral heritage. If looking for some guidance, the October edition of Family Tree Magazine, dubbed a #househistory special, is a great place to start. Not only does it feature an exclusive interview with the show's presenter, Professor David Olusoga, but editor Helen Tovey dives behind the scenes for a sneaky peek into the making of the programme. (A link to Helen's interview with Mary Crisp and Caroline Miller, two of the show’s producers, is included in this month's newsletter.) The magazine also contains a guide to using maps, practical house history case studies and the top ten sources for researching ancestor homes from Kathryn Feavers. Kathryn has been a member of the research team from Series 1. These are great, and many of the sources will already be familiar to readers but there are always more! I recently had the chance to take a short walk around Berwick-upon-Tweed 'old town'. I love to lose myself in the views of the sea from the Elizabethan Walls. I can imagine the 'Smacks', other sailing ships and boats waiting to be loaded with local goods, or, to spill their precious cargos from further afield onto the old quayside. The town is packed to the gunwales with so many intriguing buildings and interesting architecture it is easy to visualise the streets, yards and alleyways bustling with colour and activity during different periods of history. This month's blog seems a great place to share a few insider tips on where to find additional information. And for a local flavour what better place to start than Berwick. 1. Maps and Town Plans I am in complete agreement with Kathryn that maps are a great place to start. With a good run, it is possible to compare landscapes both rural and urban over a long period. Many historic maps and town plans are available through the National Library of Scotland. Amongst them is John Wood's detailed town plan of Berwick from 1822. Wood's series of maps of Scottish towns are particularly useful as they pre-date the census by some 20 years and contain a scattering of names of the proprietors. The accompanying book containing descriptive accounts of his town 'atlas' and some fascinating snippets of historical context, is available through Archive.org. The entry for Berwick begins on page 48. Looking at the route of my recent walk on Wood’s 1822 map, the space surrounding the buildings in Palace Street and Wellington Terrace is quite striking. There almost appear to be fewer buildings than depicted in John Speed's map of 1611 above. The new Governor's House and grounds built in 1719 to house the Governor of Berwick Garrison, dominates the east side Palace Green in blissful solitude. Thirty years later the large-scale ordnance Survey map of 1852 shows the area to have an Industrial School, the Tweed Brewery, a Bowling Green, Readings Rooms and several new homes. 1852 also bears witness to the importance of the corn trade, with many large granaries occupying the roads adjacent to the Quay Walls. 2. Listed Building Register (Historic England & Historic Environment Scotland)Most buildings in England that pre-date 1840 have a 'record'. Thus, if a building is old it is always worth checking to see if it is 'listed'. A search of the relevant registers of England and Scotland is easy and free. Entries include more detailed descriptions of the architectural features or historical significance of a building or the reason for its inclusion. They are often brief, but at times the records contain some great nuggets of information. This Historic Buildings Report attached to the entry for 84 Ravensdowne is a fantastic example of what it may be possible to find! Locating the stories of the people though, will most often require investigation elsewhere. The western gable of No 1 Wellington Terrace (the home of John Miller Dickson (1771 – 1848) has always intrigued, with its blanked off windows blinding the view towards Tweedmouth. A house on the Walls at the corner of Wellington Terrace and Palace Street is known today as the 'Old Whaling House'. It appears on the 1852 map as 'Bay View'. At one time Berwick was also a whaling port, albeit on a small scale. The ship 'Norfolk', famed for surving an ice-bound winter in the Davis Straits in 1836 was the property of John Miller Dickson, the owner and occupant of 1 Wellington Terrace. The old ' whale oil' refinery stands on Pier Road. It is now flats with fabulous views over the mouth of the Tweed with its pier and lighthouse, and to the sea beyond. 3. Berwick upon Tweed 'Our Families Project'A searchable database for High Greens, Low Greens and Ravensdowne, created as part of the HLF 'Our families Project' organised by Berwick Record Office, is also available online. The database contains information collated by volunteers from censuses, electoral registers, parish records, newspapers and other sources. It's a great little resource but very sadly Berwick specific. Nonetheless, it is an example of the type of information available for a specific property investigation. It is accessible via The Friends of Berwick and District Museum and Archives website. 4. The Berwick Directory of 1806Trade Directories are another 'go to' for information on a place as well as its people. The Berwick Directory of 1806 provides a glimpse of the town and its community during the Georgian era. The layout allows for searching by surnames, streets and place names, trades and professions, carriers and public houses. (Backway was one of the alternative names used for Ravensdowne, as was Union Street but neither 'stuck'.) The National Library of Scotland holds Scottish Post Office and other Trade Directories, such as 'Pigots' and 'Slaters' for Scotland. The 1837 Scottish edition of Pigot's also includes Berwick upon Tweed and a few other important 'towns' in England as well as the Isle of Man. The directories are free to access and download. 5. OS Place NamesIf looking for places that no longer exist, Ordnance Survey Name Books are worth a try. Thanks to the project 'Northumberland Name Books — Places and People c. 1860' names of places in Northumberland, recorded by the Royal Engineers surveyors and aided by local civilians 'in the know', are available to search online. (This site carries a 'rabbit hole' warning! I looked at the page for Longhoughton and although I recognised many of the old names, such as Letch Houses that appear in a family tenancy agreement of 1872, I confess many were new to me. One that was unfamiliar and caught my eye was 'Broken Stirrup', a gully in Ratcheugh Crag) The Scottish OS Name Books are accessible free through Scotland's Places. The website also contains a plethora of other information relating to property: Land Tax Rolls 1645 - 1831, Window Tax 1748 – 1798, Cart Tax Rolls 1785 – 1798, Farm Horse Tax Rolls 1797 – 1798, as well as old maps, drawings and photographs. 6. Valuation RollsStaying north of the Border, the Valuation Rolls available through the Scotland's People Website can also be enormously helpful when tracing the history of a property and its occupants. As well as homes, these records also include business premises such as farms, shops, churches, schools and a few oddities such as railway stations. Their purpose was to assess the rate of tax due on a property. The assessor in each county or parliamentary burgh compiled annual valuation rolls, listing most buildings and other property in their areas, along with the names and designations of the proprietor (owner), tenant and occupier, and the annual rateable value. The records cover the period 1855 – 1940, and there is a helpful guide to using these records on the Scotland's People Website. The Index is free to search, but to view or download a record will cost 2 credits or 50p. Although it is possible to search by parish and place it can be a little tricky identifying a specific property as street names and numbers were often absent in the earlier records. Knowing the surname of the owner, occupant or neighbours will help a lot. The level of information provided in the returns varied year on year. But as the records were created for tax assessment purposes, they do have their limitations. 7. DeedsDeeds are a large, complex and interesting topic that deserve a blog of their own. Only a very brief overview appears below. For present-day enquiries, a search of the Title Registers held by the relevant Land Registry for each Country will establish the current owner and extent of a property. For England, this is HM Land Registry, and in Scotland, the Scotland Land Information Service through the Registers of Scotland. In Scotland before the introduction of the Land Register, Deeds (or Sasines) relating to land and property were recorded in the Sasine Register. Some sasines are accessible through Registers of Scotland but the National Records of Scotland holds the majority. Click here for the NRS online guide to sasines and searching the sasine registers. Alternatively, there are various companies and organisations that (for a fee) will help navigate the systems and obtain the available property records for you. In England, local record repositories and archives often hold historic Deeds and other documents associated with land transactions. Transactions in land to prove ownership have been recorded since the Medieval period. Transactions in Freehold land came in different forms; Gift, Quitclaim, Letters Patent, Bargain and Sale, Lease and Release, Feoffement, Final Concord, Common Recovery, Deed of Covenant and Grant or Conveyance. More details on their specific purpose and distinguishing features can be found online in an 'Introduction to Deeds in Depth' at The University of Nottingham. They also appeared as hybrid documents such as the transcription extract taken from a document dated 1640 held at Berwick upon Tweed Record Office. It is for the Bargain and Sale with Feoffement of a property in Bridge Street lying between properties belonging to William Morton, gentleman, and George Smith, Burgess. To all Christian people to whom this p[re]sent Writeing shall come I Edward Wilson of the towne & County of Newcastle upon Although introduced in 1862, land registration was not made compulsory until 1899. In Scotland, the General Register of Sasines was introduced in 1617 and was the first national land register in the world. The biggest problem is that historically only a small proportion of the population owned land and property! 8. Estate Records and Rental RollsMost land and property, particularly in rural areas, was in the ownership of a handful of individuals. These 'Estates' then let their land and property to others. As a result, lease and rental records such as 'Rental Rolls' can often be more informative on a property's history than those relating to its ownership. Although some estates on both sides of the Border still retain their records, many have made them available to the public via national or local archives and record offices. For example, Berwick Record Office holds historic Rental Rolls for the Ford and Etal Estate amongst its records. The various tenants of the farm where I grew up (featured in my July blog), were traced back to the early 1800s through rental agreements and tenancies. The associated schedules make fascinating reading and illustrate how the farm changed shape over the years to accommodate the arrival of the railway, the new road to Boulmer, the expansion of Longhoughton Village and the coming of the Royal Air Force. They also document the changes to the farmhouse living accommodation, both cosmetic and functional. At one point in time, it appears there was another floor containing four attic rooms and what would become my own bedroom, may once have been a granary. ConclusionThe eight sources outlined above will hopefully provide some inspiration for new places to research. Not only for information about your ancestors, but also their homes, other associated buildings such as shops or farms, and the area and communities in which they lived. Weaving historical context gleaned about homes and communities into ancestral information brings another dimension and dynamic to family history research Useful Links 1806 Directory for Berwick

http://rgcairns.orpheusweb.co.uk/DirectoryContents.html National Library of Scotland, Maps and Plans of Berwick https://maps.nls.uk/towns/berwick.html Historic England https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/ Historic Environment Scotland https://www.historicenvironment.scot/advice-and-support/listing-scheduling-and-designations/listed-buildings/search-for-a-listed-building/ National Library of Scotland, Scottish Post Office Directories https://digital.nls.uk/directories/index.html Scotlands Places, Berwickshire Records https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/search/place/berwickshire Northumberland County Council , Extensive Urban Survey Project 2009. List of Listed Buildings in Berwick Appendix Page 60 https://www.northumberland.gov.uk/NorthumberlandCountyCouncil/media/Planning-and-Building/Conservation/Archaeology/Berwick.pdf Northumberland Name Books, Berwick, http://namebooks.org.uk/browse/main/?OSref=154&Page=35&indexPage=1 Scotland’s People Guide to Valuation Rolls https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/valuation-rolls Nottingham University, ‘Introduction to Deeds in Depth’ https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deedsindepth/introduction.aspx Friends of Berwick and District Museum and Archives www.berwickfriends.org.uk/ ‘Biography is one of the most popular and widely read of literary genres. It can also be controversial, scandalous, and hotly debated. And it is by no means a fixed or stable form of literature. Biography has gone through many centuries of change and exists in many different versions.’[1] Documenting ancestor’s lives and bringing together family history as a narrative creates a position of both power and responsibility. Not least, over what form the account will take, what to include and what to lose to the cutting room floor. It is the culmination of years of research come to fruition. The stories of the good, the bad, the bigamous, the unmarried, the criminal or the victim all waiting to spill out onto the page. But where to begin? And is it ‘right’ to include everything ‘warts and all’ because it has been unearthed? The October issue of Family Tree Magazine contains my article discussing this issue.[2] It also covers some other considerations faced when writing ancestors stories (moral and otherwise) based on the results of a questionnaire circulated in June. The same issue contains an exclusive feature on house history by David Olusoga, presenter of BBC2’s ‘A House in Time’. A great article that builds on last month’s blog looking at creating immersive historical settings. In preparation for the companion piece focusing on the ‘practicalities’ of writing ancestor biographies, this month I look at some stylistic ways it can be easily achieved. It can be a lot of fun! Plus, many methods outlined can also act as a research aide memoir by highlighting gaps in knowledge. ‘Cradle to Grave’ is the traditional style or method favoured by family historians. It is customary to begin with a birth and follow a chronological path through life and achievements to the point of departure. But there are many other ways to approach writing family history and ancestral stories and, they don’t all have to begin at the beginning or with a birth! Here are a few alternative tactics that work well in the context of family history:

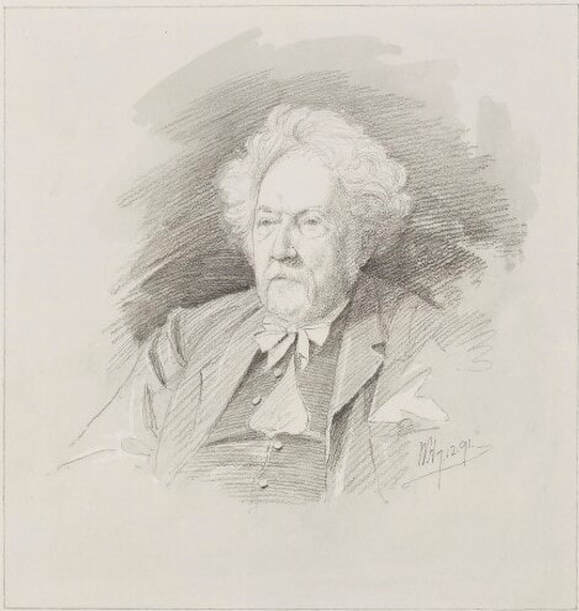

There are at least two further approaches. One will be familiar to all family historians (the Obituary style) and another that took me a bit by surprise! During five days of intensive life writing workshops, author Richard Skinner set a task to research and gather as much information as possible about a favourite ‘artist’. The research time given was one afternoon! The information amassed was to form the basis of the next day’s writing challenge. But at the time of the research, that challenge was unknown. Portrait of a Painter - Henry George Hine 1811 - 1895My knowledge of the world of art is somewhat limited, but the well-known watercolourist Henry George Hine immediately came to mind. He was the husband of a third great aunt, Mary Ann Eliza Egerton, so I already knew something about him too. An interesting man who preferred a ‘simple kindly life’ and had great stories to tell. He was a prolific artist whose pictures are rich in historic detail. They reflect a bygone era and provide powerful vignettes of social history. Those of Brighton are useful records of the town’s history with its fish quay, promenade and bathing huts. Other paintings depicting scenes such as a cattle train on a viaduct, London washerwoman at work and a fire in Drury Lane are three others that offer rich glimpses into the past. Hine himself often reflected on the Brighton of his childhood recounting the tales to friends and family along with the legend of a highwayman ancestor hanged during the time of Cromwell. My January 2019 blog also mentions the family. In it, I aim to dispel a few myths concerning the Egerton family pedigree and speculate whether coaching connections may have brought the couple together. It is only speculation, as Mary Ann was to become an accomplished artist in her own right. She exhibited a figurative watercolour at the Dudley Gallery in 1873. The couple had a staggering fifteen children of whom only one did not make adulthood. I also mention two of his youngest daughters who were founding members of the ‘Peasant Arts Society’ in Haslemere Surrey. But so many aspects of this couple’s life have an interesting back story. The history and site of Saint Marks Church, Kennington, where the couple married in November 1840, is worthy of its own chapter. But I digress! Faber Workshops & Writing Challenges• The interview or question and answer method. When Richard outlined the writing challenge the following morning, my heart hit my boots. ‘Interview your chosen artist in five questions.’ How do you interview an ancestor who died in 1895, let alone know what questions to ask? Believing myself well prepared for the day’s exercises, my confidence flew out of the window and blind panic set in. On top of this horrendous challenge was a time limit of 45 minutes. I was having premonitions of a blank page at the end of the allotted time and sitting back to enjoy my writing partner’s piece of literary genius! Where to even start such an endeavour? I looked to Henry himself for guidance and started to write … I am looking at the 80-year-old man in an 1891 sketch by Walker Hodgson. His mass of white, leonine hair is set high and Einstein-Esque above an intelligent forehead. His kindly eyes gaze over his long nose, drooping moustache and feathery beard to a point in the distance somewhere beyond my left shoulder. I imagine ‘chewing the fat’ over a cup of hot chocolate with this portly fellow with the immaculate bow tie, waistcoat unbuttoned to accommodate his form and handkerchief, wilting in a top pocket. I want to ask him about his life and experiences that culminated in the vice presidency of the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolours. A position he held from 1887 to his death in 1895. Although I didn’t finish the challenge in the allotted time, I was not left looking at a blank screen either. Yes, the first question was about where he was born, but it needn’t have been! In my haste to put words on the page, I framed the questions around answers I knew. But none of the details are fictitious and where possible, Henry’s ‘own voice’ has been used. As I began scribbling, I remembered the book ‘Round about a Brighton Coach Office’, a selection of his stories retold and published by his daughter Maude. Using extracts from the book and combining them with other known facts formed the basis of Henry’s answers. As coincidence would have it, the afternoon’s challenge was an Obituary, the style of which is popular and well-known amongst family historians. • Obituary style or ‘Beginning at the End’ As well as containing details of funeral arrangements, an obituary of a well-known figure often comprises a brief biographical overview of their life. Adopting this approach essentially begins an individual’s story at the point where it ends. The main focus is almost always specific achievements. This time there was a limit of 500 words on top of the 45 minutes of writing time. What follows is my attempt, which, although roughly completed within the time, is not great but will hopefully inspire you to give it go! On the 16th March 1895, at his home in Gayton Crescent, Hampstead, in his 84th year, renowned watercolour artist Henry George Hine laid down his paintbrush for the last time. I confess to writing the beginning and the end first and then ‘putting the jam in the sandwich’. Cheating, but at least it provides some form of narrative arc to the 481 words used! But it is the sharp contrast in language and tone between the two exercises that is so dramatic. The Q&A is more personal and the subject feels close and alive, whereas the Obituary is altogether more formal and the subject quite distant. It is interesting to see how much the different approaches affect the result in such a radical way. An interview or Q&A with a deceased ancestor is not something I would ever have thought of trying before, but it is a method and style I will try again. I can also see its benefit as a focus and framework for questions to pose to the living too! The reason for sharing the exercises above is to inspire you to be bold and have a go yourselves! Choose a style, set a clock for half an hour or 45 minutes and just get scribbling. (Setting a short time limit can be an effective motivator.) Then, why not share your results with others. They may look differently on family history after reading your work! [1] Hermione Lee. Biography A Very Short Introduction. Oxford 2009. [2] Family Tree Magazine, October Issue on sale from the 10th September either in print or online https://www.family-tree.co.uk/store/back-issues/family-tree-magazine Useful LinksSt Mark's Church Kennington,

https://stmarkskennington.org/about/history/ Explore a further selection of Henry's Paintings at Watercolour World www.watercolourworld.org/search?query=Henry+George+Hine&displayCount=24 A highly informative website about the peasant art movement and its people. Peasant Arts - Haslemere http://peasant-arts.blogspot.com/p/introduction.html A wonderfully illustrated copy of Henry's tales retold by his daughter Maude. Archive.org 'Round About a Brighton Coach Office' Maude Egerton King with illustrations by Lucy Kemp Welsh. https://archive.org/details/roundaboutbright00king/page/n9/mode/2up A great narrative does not have to be fiction and writing creatively does not make an account less factual! Creating a rich setting provides the theatre in which characters can be expressed and allowed to re-enact their stories. For many family historians, the pleasure of research lies in sharing discoveries or entertaining others with ancestral tales. For some, it is the enjoyment of immersion in old documents and learning about times gone by. For others, it is the desire to create a legacy for generations to come. But for all, the question of how to record it all will doubtless arise at some point! There is the traditional method of recording information in a family tree accompanied by a report containing dates, facts and endless citations. But if looking to go beyond the time-honoured route, a written narrative account may be the answer. Nonetheless, the style and format of any account are dictated by the intended audience. Traditional family history reports are fine for other family historians. But they don’t and won’t cut the mustard with non-genealogy minded folk! To keep them reading beyond the first page requires a more sensory approach and language that captures the imagination. Writing a factual family history, a biographical account of a specific ancestor or about the place where ancestors lived needn’t be dull. Cast your mind back to books you have read. What is it about them you enjoyed? I have recently finished ‘Inge’s War' by Svenja O’Donnell.[1] Taking advantage of the hot weather I sat in the garden and read the account of her grandmother’s life in Germany during WW2 from cover to cover. It is an example of a family history narrative at its best. Meticulously researched, yet the language is highly accessible making it easy for the reader to engage with her story. It is sensitive and compelling but remains honest and factual. Creating Setting for Historical NarrativesLike any other account, the historical narrative needs to contain specific elements. Setting is one of the most important as it conveys a sense of place and time as well as providing the backdrop and mood for characters to play out the plot. I have been having some fun of late indulging in a bit of memoir combined with house history and a 1,000-word challenge. The house and farm where I spent much of my childhood and adolescence have a history that stretches back several centuries. The house’s listing with Historic England dates it from the late sixteenth - early seventeenth century. [2] But I am also lucky as many records have survived which show how they have changed and evolved over the years. I was the fifth generation in my direct paternal line to have lived there, thus I remember it well.

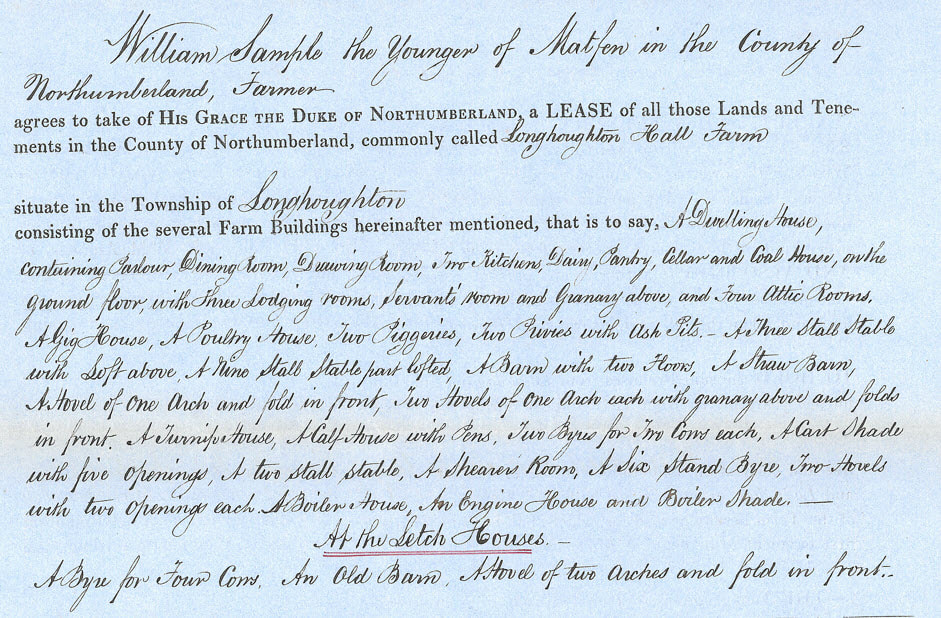

It doesn’t always need a photograph to generate a visual on which to base more sensory images. This extract from the rental agreement for our predecessors in 1853 paints a picture of a very different internal layout than the one I remember or exists today. These differences account for the strange levels of old doorways and windows which can still be seen both inside out. Instead of producing a literal account, it is possible to create a more dramatic feel for the idiosyncrasies without compromising the truth.

In the 1000-word challenge, I went a step further, humanised the house and treated it as the central character. By creating analogies between the house as a mother caring for her children, and, as a collector of the souls of previous inhabitants, it suited the purpose of the story I was trying to tell. Below are some examples of sources that will provide valuable information to help create a setting rich in historical detail and context.

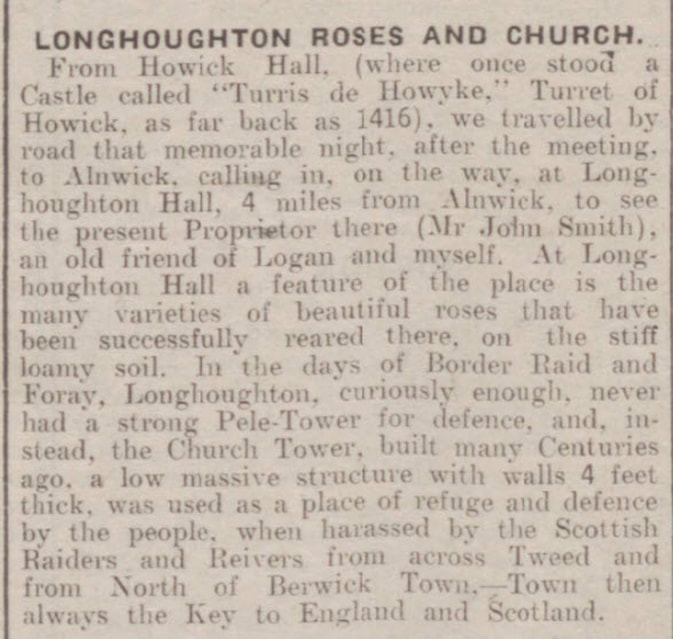

The garden of my early childhood in my grandparents' day has also radically changed. Granny Smith loved her flowers; a large bed in the centre of the top lawn provided what seemed to be an endless supply of Dahlias and Chrysanthemums. There was a dry fishpond, a concrete-lined crater surrounded by crazy paving and French Marigolds. But it is the rows of rose beds separated by parallel gravel pathways I particularly remember. It was this interesting little snippet found in the newspapers that brought it to mind. Although the paper appeared in 1934, the article relates to recollections of a journey made 40 years earlier in 1895.

My recollections of the structure of the house continue:

The next step is to introduce atmosphere. Setting and sensory description is often lacking from traditional family histories and other historical accounts. Again, as well as engaging the reader it is important to remember the contract to provide a truthful account. In my 1000-word challenge, I drew heavily on personal memories of sounds, smells, taste and touch.

The smallest detail or object can add mood and ambience as well as focus and interest. Whilst helpful for setting, the sources listed above also contain information about the human aspect of a property or place. When combined with the records commonly used for researching family histories, such as Birth Marriage & Death and the Census, it is possible to draw together a chronological account of previous inhabitants.

There is enough information about the place and its people to write several chapters of a book. This extract is a brief glimpse, but it needed to be. Context and relevance are key for both narrative and content. A tight word count focuses the mind and curtails an over-eager pen! Writing a family, house or any other history may seem a daunting prospect. Try starting small with a series of small challenges or vignettes written in 1,000 words or less. It’s amazing how much can be said in under 500 words. These exercises are great for building confidence and also for providing material for a much larger work. Remember, a great narrative does not have to be fiction and writing creatively does not make an account less factual! Creating a rich setting provides the theatre in which characters can be expressed and allowed re-enact their story. A two-part article on the topic of writing family history narrative will be published in Family Tree Magazine. Part I which considers the principles, (moral and otherwise) together with the potential pitfalls, will appear in the October issue on sale from the 10th September. It is based on the responses to a public questionnaire circulated in June. If you were one of the 75 individuals who took part and shared their views, very many thanks indeed. Your opinions matter and they were fascinating to read! Part II will focus on the practicalities of writing family history in its several forms. If you have written a family history or are writing your ancestors' stories as a narrative, tried to write but given up, or would like to give it a go but don't know where to begin, we would love to hear from you. The questionnaire is anonymous and contains only seven quick questions. It will be open throughout August. The results with a selection of your comments will appear in the December issue. As research can be a solitary pastime, so can writing. Getting together with others, in a small group, or even just one other individual can provide moral support as well as helpful feedback and suggestions. Content, Context and Construction are topics I intend to cover in workshops with small groups over the winter months. If you think these might be of interest, please contact me for further information. If you enjoyed this post why not subscribe to the Free monthly Blog and newsletter and never miss a thing! Useful Links[1] Penguin Books, Svenja O'Donnell, 'Inges' War - A True Story of Family, Secrets and Survival under Hitler'

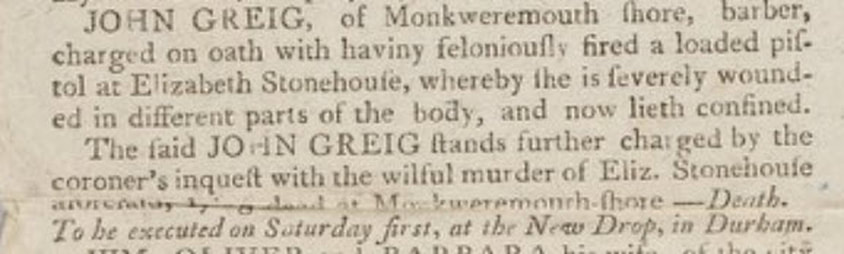

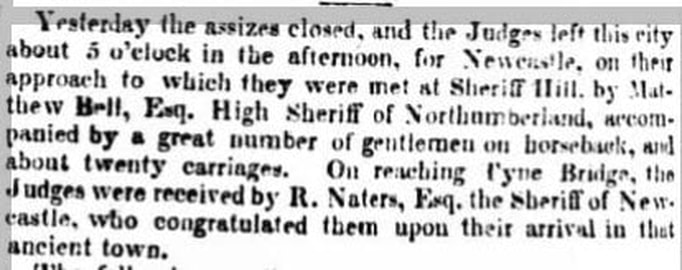

https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/111/1118767/inge-s-war/9781529105476.html [2] Historic England, Longhoughton Hall, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1041774 At 9.00 am on Saturday 17th August 1816, John Greig, a Barber and Publican from Monkwearmouth Shore was hanged outside Durham Courthouse. He was the first person executed at Durham using the ‘new drop’ method, where the condemned entered the afterlife via a trapdoor. He had been found guilty of the ‘wilful murder of Elizabeth Stonehouse’ at the Summer Assizes. His hearing lasted just five hours. To modern standards, five hours seems a ridiculously short duration for a trail of such gravity, but to an early nineteenth-century audience, a five-hour hearing was a long one. ‘The actual trials were often very quick; in 1833, at the Old Bailey (an Assizes court), it was estimated they averaged 8-9 minutes.’[1] Indeed, the press bemoaned the length of John’s trial as there was insufficient time to print details in the following day’s newspaper. Hence, details of the court proceedings do not appear until the following Saturday, 24th August, together with the details of his execution.

The doctor attended her at the home of Matthew Briggs shortly after the incident. As well as treating her wound, he observed a ‘large mass of disease’. Bet died on the 22nd of April 1816, some 18 days after the shooting occurred. Nevertheless, the cause of death recorded is as a result of the gunshot. This accounts for the two separate charges recorded against John in the Calendar of Prisoners for August 1816. The first for shooting and maiming, the second for her murder. A copy of the Calendar in full can be viewed online at Harvard Library Curiosity Collection It is not clear whether there was any truth in Bet’s accusations, but to date, I have found no evidence to substantiate her claims. Bet, who was born Elizabeth Parkin in 1768 does not appear to have had an easy life. Records suggest that her father Charles Parkin may have died when she was young. Aged 21, she married Samuel Stonehouse at Bishopwearmouth in January 1789. Samuel was a mariner who would spend much time at sea - he was reported to have been at sea at the time of the shooting. The couple had eight children born between the years 1789 – 1805, but only 4 survived beyond childhood. Suffering this type of loss, at times without the support of her husband must have been difficult for her. Even so, it still does not explain her accusations and why she appears to have targeted John Greig. As for John, he appears to have remained unrepentant of his actions but accepted the justice of his punishment. I suspect there is still more to this case than meets the eye. Where to start looking for records of criminal ancestors depends on the period and gravity of the crime they committed. The more serious the crime the ‘higher’ the court. Hierarchy of The Historic English CourtsThere was a hierarchy of courts dealing with crime and criminals outside of London at county, regional and national level. The judicial system and type of cases they each heard has evolved through the centuries. Until circa 1500, an annually elected Sheriff was responsible for dealing with crime and criminals at county level. Coroners who investigated sudden and violent deaths assisted him. They reported suspected murders to the Sheriff, who dealt with them through his Court. After this period the Sheriff's court dealt with civil cases only. Even so, the Sheriffs and Coroners could still ‘outlaw’ accused individuals who failed to appear at trial in a higher court. In the early modern period, Church Courts and Manor Courts also played a leading role in the trials of petty misdemeanours. These courts heard the majority of petty cases until the Restoration. The most important officers of the County judicial system were the Justices of the Peace. Drawn from the County’s landed gentry there would be several in office at any one time. Acting on their own or in pairs their ‘powers’ were far-reaching. Nowhere more so than acting as ‘judges’ over the Quarter Session Courts. Assisted by grand and petty juries, they could try more serious criminal cases. They could also determine the punishments for those convicted. Above the Quarter Session Courts were the regional Assize Courts who were answerable to the Privy Council. Local criminal cases could also be transferred to the Court of the King's Bench in London if required. The various regional courts outline above heard civil as criminal cases. They also dealt with many aspects of local administration. Below is a brief description of the courts in operation in the early nineteenth century and the types of criminal cases they heard. Petty Sessions Court These are what we know today as the Magistrates Court. Formed in the 18th century from Quarter Sessions they heard more minor cases, such as poaching, drunkenness and vagrancy. It was a court of ‘summary jurisdiction’ whereby the Justices of the Peace could decide on a sentence without the intervention of a jury. Their records are usually held by the local Records Offices. (NB. From the 19th century onwards the Petty Sessions also heard cases of illegitimacy. These cases are sometimes recorded in separate ‘Bastardy Order Books’.) Quarter Sessions Court As the name suggests, the Quarter Session courts met four times a year, in January, April, July and October in Counties and Boroughs with the right to try criminal cases. They are normally associated with a county but some boroughs and cities could also hold their own courts by a grant of royal decree or charter. Presided over by the justices of the peace and two juries, they heard more serious criminal cases. The cases heard were not usually for capital offences, but there were exceptions. ‘Before 1842 the line between Assize and Quarter Sessions cases was rather blurred; an Act of that year consigned all capital offences (those that carried the death penalty) and also cases with sentences of life imprisonment, for the first offence, to the Assizes.’[2] Some boroughs such as Berwick upon Tweed could and did, try crimes attracting the death penalty as their records will testify. As with those of the Petty Sessions, the Quarter Session records are held in local archive offices. The Assize Court Before 1972, the Assize courts were the highest regional courts in England. Their origins date from the Medieval ‘Eyre’ courts where judges sent in the King’s name from Westminster administered justice in the counties. They were traditionally held twice a year; February/March in the Spring, and July/August in the summer and operated in six ‘circuits’ of contiguous. The exception was London, the permanent home to the Assize court known as the Old Bailey. The Assize Courts typically heard capital cases that carried the death penalty and other cases too serious for trial at the Quarter Sessions. In 1815 there were no less than 215 crimes which (in theory) could attract a penalty of death. Amongst them were:

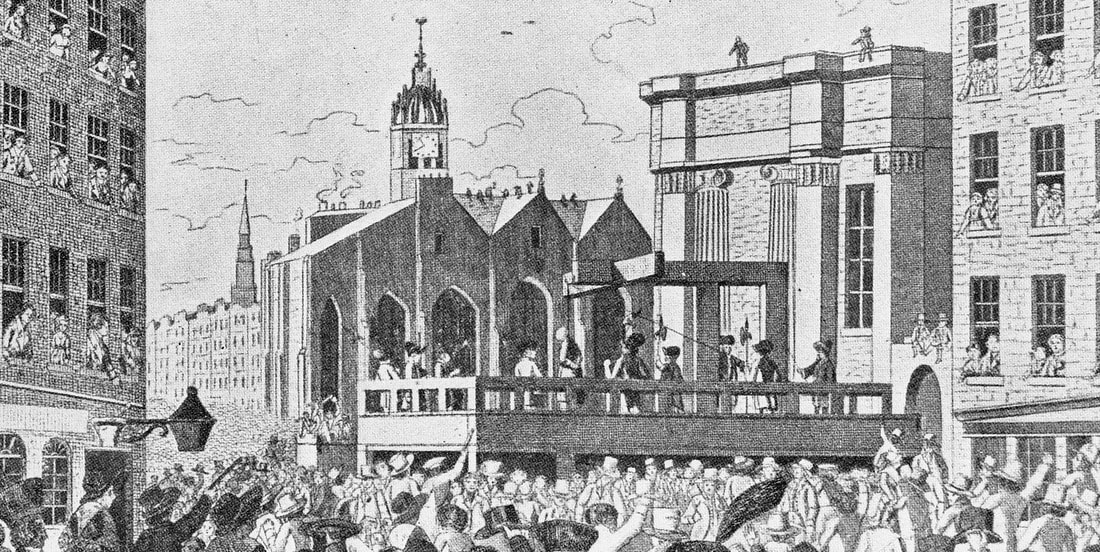

This number, sparked by social, economic and political changes had risen sharply from 50 in 1688. It was the time of what became known as the ‘Bloody Code’. Stealing 5 shillings (about £30) or being out after dark with a blackened face could result in hanging. In 1816 the two assize judges, Sir George Wood, Sir John Bayley their clerks and their retinue arrived in Durham on Saturday 10th August. Sir George Wood presided over the cases ‘for the Crown’, (the criminal cases) and Sir John Bayley dealt with matters of the Civil Court (land disputes etc.). Court proceedings commenced on Monday morning following. As at the Quarter Sessions, the Grand Jury decided which cases to present for trial. They had the power to decide which cases to dismiss, either as there was insufficient evidence or no case to answer. The Grand Jury also heard witness statements and prepared the indictments for cases being be brought before the court. If a case was to be tried, then the Petty Jury or Trial Jury was sworn in to hear it. It was they who would decide the verdict. ‘Each trial started with the clerk reading the charge again, and then the prosecutor presented the case against the defendant, followed by the witnesses, who testified under oath. Witness testimony was the most common source of evidence and Judges frequently intervened to ask questions or comment. The defendant was then asked to state his or her case. They could call witnesses, if they had any, and use a defence lawyer.’[3] The newspapers record that John Greig made no case himself in his defence but ‘called several witnesses to speak to his character, all of whom spoke highly in his favour.’ That week there were five other individuals sentenced to death. Two for stealing horses, one for stealing 3 heifers, one for killing a sheep and stealing the carcass, and one for stealing £5 in silver coin. All bar John received reprieves, most likely having their sentences transmuted to transportation. (An interesting aside is that Anne Stonehouse also appeared on the Calendar of Prisoners for the same session. Charged with ‘concealing’ the birth of a child, the Grand Jury dismissed her case before it came to trial. Whilst it is not known if any connection existed between the two Stonehouse families, it is a rather ironic twist of fate.) The assizes often lasted a week to a fortnight depending on the number of cases to be heard. Like the Quarter Sessions, the Assizes involved a lot of people and were important economic occasions for the host town. Bringing in many people, much business and money they were social highlights of the year. This extract from the Durham Country Advertiser describes the arrival of the judges and their retinue in Newcastle the following week. John Greig’s execution would have marked the culmination of the summer Assizes and associated jollities. Thousands would have gathered in what is now Durham Crown Court Gardens to watch the public spectacle. Unlike Petty Session and Quarter Session records, the National Archives holds the Assize records. A table and key to those that have survived are listed here (It should be noted that whilst Chester, Durham and Lancaster had their own assize jurisdictions, their surviving records are also held at Kew.) Documents Associated with Courts and Criminal Trials The judicial system generated various types of records, the most common are briefly outlined below:

Newspapers or other publications are another great source of information relating to a trial. (They are sometimes the only source too). Newspapers often contain an account of the proceedings of the trials themselves. A prime example of publications at work are the 'Proceedings of the Old Bailey 1674 - 1913' which are freely available online. In the case of John Greig, later articles tell of his last night in prison and collections for his widow and family. These say far more than a formal court document or testament ever could. [1] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes, http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html [2] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes, http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html [3] Victorian Crime and Punishment, Court Procedures, The Assizes http://vcp.e2bn.org/justice/page11548-court-procedures-assizes.html Useful Links & PublicationsOnline

Publications

Family history researchers are increasingly turning to autosomal DNA (atDNA) to help extend their ancestral knowledge and it is little wonder as it can be an immensely powerful tool. But are folks using atDNA testing to maximum effect? I suspect in a great many cases the answer is no. There are a myriad of reasons why this is the case but it is not my intention to cover them here. Rather, I shall be keeping this post simple by looking only at matches in Ancestry.com and focusing on three basic principles that can greatly enhance your chances of success. I cannot emphasise these three points enough:

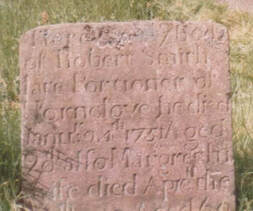

Test as Many Family Members as Possible Memorial Inscriptions in Cornhill Churchyard: These inscriptions were noted in 1918 and by the time these photographs were taken in 1986 much of the writing had already been lost. Today they are barely legible. 'Here Lyeth the body of George Smith who died 8 October 1690. Here rests also the body of his wife Elizabeth who died 2 July 1701' (Stone left and Centre) and 'Here lyeth the body of Robert Smith Portioner in Hornclove who died 22 January 1751 aged 90. Also Margaret his wife who died 27 April 1742 aged 60' (Stone to the right.) Testing relatives acts like signposts or way markers, giving us fixed points from which to start navigating the way through our DNA matches, from known points of shared ancestry towards the unknown. But before dashing off to purchase tests for every aunt, uncle, cousin etc., it is helpful to remember three basic principles to ensure the tests being purchased are relevant to your quest.

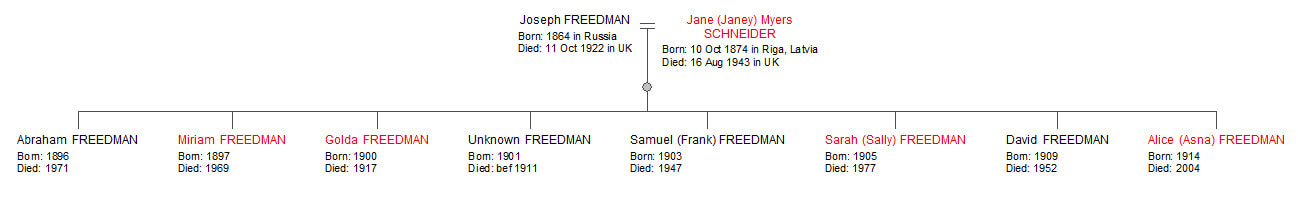

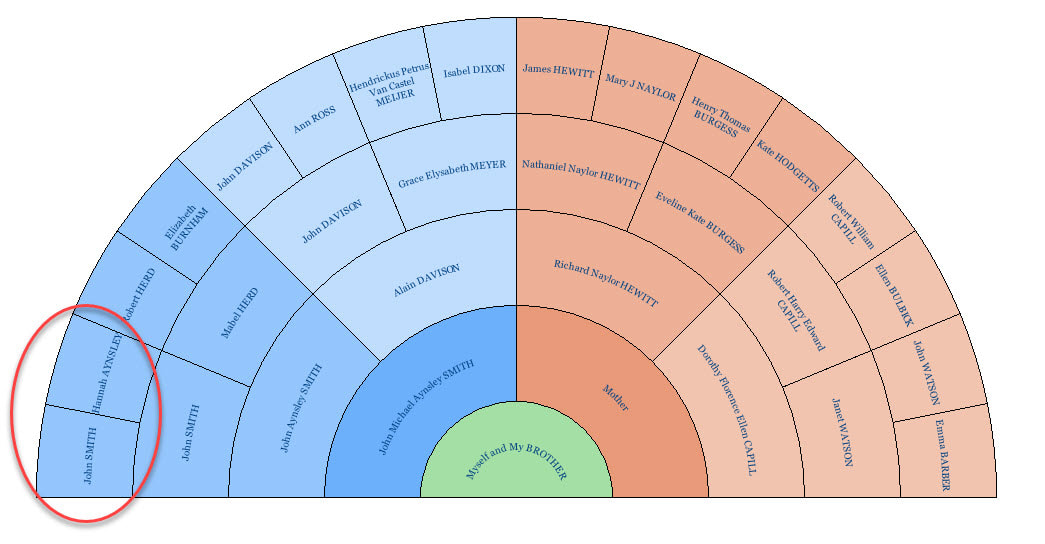

It is also important to recognise which relatives are relevant to test for a particular research scenario. For the remainder of this post I shall be using my tree, my DNA matches, and the DNA matches of my relatives who have also tested using an example of a specific paternal line hypothesis which came to light as result of this broader testing policy. It reveals connections to renowned Australian convict Ralph Hush, previously hidden from view due to a smokescreen of ‘selective’ genealogy that without atDNA may have remained undiscovered. I hope it will also illustrate what can be achieved from what essentially started out as set of dismal results. After many years, I still have only 149 matches in the Ancestry database with whom I share 20 cMs of DNA or more. My brother on the other hand has a slightly more respectable 229, that is 80 more individuals for whom Ancestry will currently display mutual matches. Although I have one or two sticking points in my tree, I have no specific ancestor mysteries to solve therefore my interests lie in uncovering all aspects of my ancestral past; but who do I have available to test?

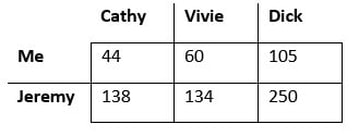

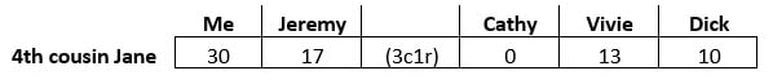

Scenario One – Maternal Line Ancestral InvestigationsMy mother is very much still with us and has tested her DNA. Should I wish to investigate any generation of my maternal line my brother’s DNA will be of no additional benefit. Some of the maternal DNA my brother and I share will overlap and some will be different. Nonetheless, neither he nor myself will have inherited any DNA that our Mother does not carry herself. Nor will our combined DNA reflect the total genetic information carried by our mother. Approximately 25% will inevitably been lost during the recombination process as we were created. Her identical twin will share exactly the same DNA as my mother and therefore will add no new genetic information to the investigation either. Nor will her children, (my first cousins), as the only DNA relevant to the investigation will have been inherited from their mother who is genetically identical to mine. For this reason these cousins will share nearer 25% of their DNA with myself and my brother rather than 12.5% making them genetically half siblings rather than first cousins. My mother’s other living sibling, however, is definitely one to test, as although some of the DNA she has inherited from her parents will be the same as that carried by the twins, some of it will also differ. On the same basis, the DNA of all three children of Mum’s deceased sibling will be relevant as they will carry portions of their mother’s genetic information which, as above, will have significant elements of overlap but crucially also elements that have not been inherited either by Mother or her other siblings. Scenario Two – Paternal Line Ancestral Investigations As my father is deceased, my brother’s DNA will be extremely useful if not vital to any investigation of my paternal ancestry. Although we match on roughly 45 – 52% of our total DNA (both maternal and paternal), the remainder is different. Even so, we are likely still to only reach around 75% of the DNA my father once carried himself. As my father had no siblings and his only first cousin available to test is unwilling to do so, the testing net has been cast wider to encompass his Aynsley-Smith second cousins, three of whom to date have been wonderfully helpful in this regard. Sisters Cathy and Vivie, and their first cousin Dick. Each shares a varying amount of DNA with both my brother and myself.  According to the Shared Centimorgan Project I share below the average (122 cMs) for a second cousin once removed (2c1r) relationship with all three and my brother Jeremy shares above. In fact, the whopping 250 cMs he shares with Dick is above the average (229 cMs) for a straight second cousin relationship, and this has paid real dividends. (It should be noted that the children of my father’s 1st cousin, (my own 2nd cousins) could also be tested but although they are a closer relationship to me, they are genetically further from the ancestral DNA, and in this particular case not as relevant to the investigation.) In terms of my paternal line research, testing to date has provided the following DNA signposts: My brother and I represent the DNA from ALL our father’s ancestral lines and thus could theoretically match with descendants of any of his blood relatives at any point in history. The DNA we share with our 2c1r Aynsley-Smith cousins, however, immediately catapults us genetically back to our 2nd great grandparents on our direct paternal Smith line. This is where the respective ancestral pathways between the 2c1r cousins merges with John Smith (1813 – 1881) and his wife Hannah Aynsley (1837 – 1922). In the absence of any closer relationship, the DNA my brother and I share with our Aynsley-Smith cousins MUST have been inherited through this couple. It therefore represents the DNA inherited from their own respective ancestors. Interestingly, when our 4th cousin Jane (a 3rd cousin 1 removed to Cathy Vivie and Dick) on the same Smith line is added to the mix, the picture changes somewhat and I become the highest match of the five. Cathy shares no DNA with Jane at all, such is the fickle nature of atDNA! Matching Mutual Matches to each other Before my brother and Dick tested their DNA with Ancestry, my paternal line research through DNA matching had stalled. I have only one mutual match with Cathy and Vivie which we believe from mutual matches of the mutual match, may relate to ancestors of Hannah Aynsley although we have yet to place them in the family tree.

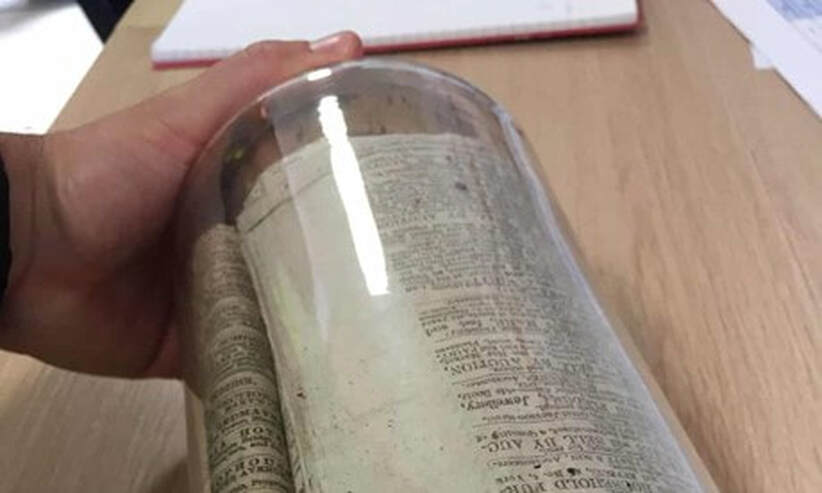

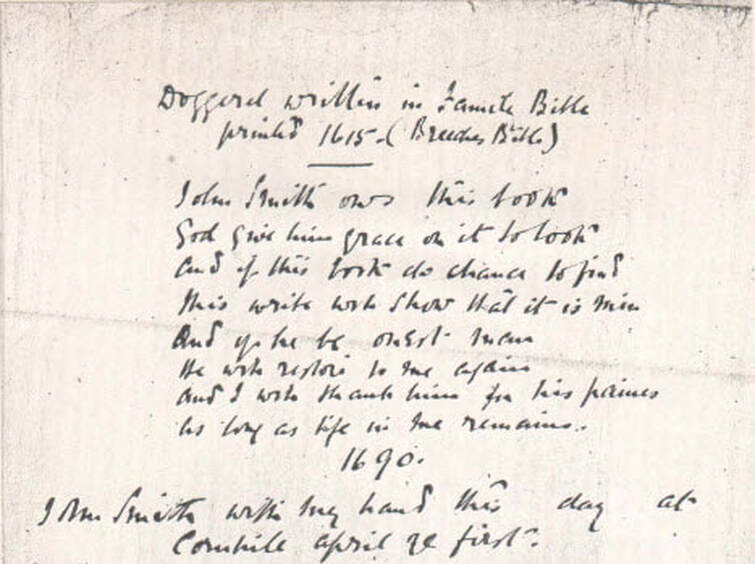

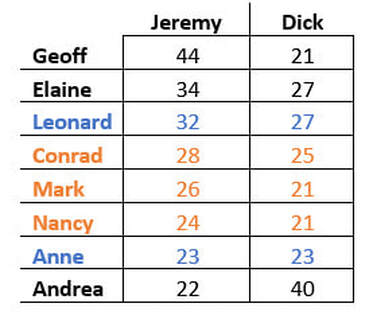

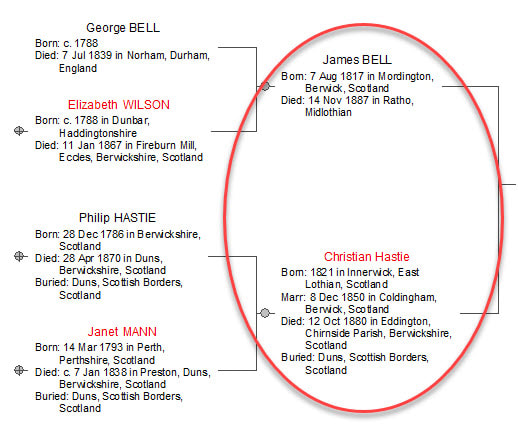

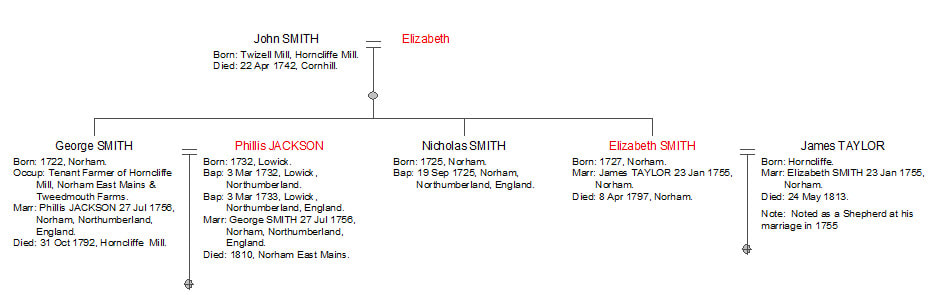

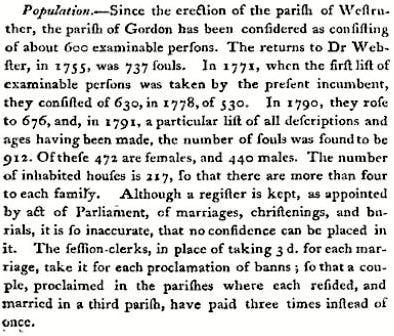

Step One in the matching process was not to try and establish how these individuals matched my brother and/or Dick, but to try and establish some commonality as to how the matches were related to each other. The main reason for this is that the way in which matches match each other will generally be the way in which they link to the tester, or where the link to the tester springs from. This approach is particularly helpful if the relation that connects matches to your mutual ancestors is not yet in your family tree. Some of Dick and Jeremy’s matches already had small family trees but some invariably had none. As with any aspect of DNA matching it will be necessary to do some legwork, particularly reconstructing matches’ trees and spotting errors in those that already exist; how much work depends on the quality of information you have to work with. It varies every time! Conrad, who had a reasonable tree of 98 individuals was the first port of call. His research very quickly suggested he may share great grandparents or 2nd great grandparents with Mark (who has no tree) in Joseph Hibberson (1812 – 1890) and Mary Ann McCarthy (1831 – 1903) making Conrad and Mark 2nd to 3rd cousins with each other. This was a positive start as the relationship is not too close and date wise, it is also a similar generation to the point at which Dick and Jeremy’s pedigrees collide with John Smith and Hannah Aynsley. Mary Ann McCarthy’s mother was recorded as Phillis Hush, and she in turn was the daughter of Ralph Hush (1784 – 1860) and Margaret Robinson (1784 – 1862). Whilst the name did not appear in my family tree, the surname Hush was ‘ringing bells’. Bypassing the matches with no trees at all for now, Nancy had a small tree with 7 people from which it was possible to quickly build her pedigree back through her grandmother Margaret Dunlop Hush to a William Hush baptised at Spital in 1778, the same day as his sister Elizabeth Hush. The parents of these two plus an unnamed child in 1779 together with a Margaret Hush baptised at Spittal Presbyterian Chapel in 1781 were Ralph Hush senior and his wife Sarah Taylor, of ‘Long Reach’ (Longridge) whose name DOES appear in my tree. From the fact that Mark, Conrad and Nancy all matched each other it was beginning to look likely that this couple were also the parents of Ralph Hush junior, the father of Phillis above. A further DNA match, ‘Jim’, at 19 cMs to my brother whose line traced back to William Hush 1778 was another mutual match to them all which would further evidence this hypothesis. From my initial investigations to date it appears that the relationships between these four are broadly as follows: Mark & Conrad 2 or 3rd cousins to each other 6th cousin to Nancy 6th cousin to Jim Nancy 4th cousin to Jim Dick & Jeremy 6th cousin once or twice removed to Conrad, Mark, Nancy and Jim Elsewhere, Leonard and Anne appear to be first cousins to each other and their paths converge with ‘Ernie’ who is another match of 22 cMs to my brother (but who does not match Dick) at a James Bell (1817 – 1887) and Christian Hastie (1821 – 1880). As well as Leonard and Anne, Ernie is also a mutual match to Conrad, Mark, Nancy and Elaine, but the potential upward link to John Smith d. 1742 and Elizabeth his wife has not yet been identified. Distant relationships such as these have a great many ‘steps’ between individuals to establish the common connection or mutual ancestor. This example illustrates just how essential it is to have a family tree that is as broad as it is deep when looking to prove relationships that are hidden way back in the past. Build Out Your Tree in Every Direction As a family we are extremely fortunate in this regard as we have been left a legacy of family memorabilia and generations of extensive research. However, it is still not complete, as I don’t believe any family history ever truly is! There are always more relations to unearth and more information to discover. This branch of our family tree was no exception. Sarah Taylor who appears in my tree was born circa 1757 and is recorded as the daughter of James Taylor and Elizabeth Smith. Elizabeth Smith was the daughter of John Smith of ‘Horncliff Mill’ who was buried at Cornhill on 22 April 1742. It is believed the Christian name of John’s wife was Elizabeth but to date there is no hard evidence to back this up. It is, however, thought most unlikely to have been an Elizabeth Davidson widely reported online, who married a John Smith at Norham in 1694. A Bible, which was printed in 1615, is still in the family’s possession and the first entry for the birth of a child is George smith in 1722. I hardly think the couple would have had their first child after 28 years of marriage! Plus, if Elizabeth was ‘say’ 20 at the time of her marriage, she would have been aged 48 at the time of the birth of her first child! I rather think that the union identified either belongs to either a first marriage, an earlier generation, or a different family altogether as Smith is hardly an unusual name! In my tree next to Elizabeth Smith’s entry there is a note, ‘see ‘Taylor’ in Sarah Nicholson’s letters’. Sarah Nicholson (1843 – 1932) was an avid correspondent on all things family history and exchanged at least 32 letters with George Aynsley-Smith between 1909 and 20 December 1931, less than a month before her death on 13th January 1932. The Taylor family are mentioned in several of the letters. The first is dated 16th July 1912 in which Sarah wrote: There is a Miss Dodds, elderly, come to live with Mrs Lyle. She came from Bowsden and told Jane [Sarah’s sister] one evening that her grandmother was a cousin (1st cousin) of your grandfather Smith, so I went and saw her. She says her grandmother was a Taylor and they lived in Horncliffe as her grandfather Taylor fell down the bank and was lame ever after. There were 5 sisters Taylor: her grandmother married a Lyle , one married a Sanderson, a weaver at Norham, one a Bolton, one a Roxburgh Loaned and one a name I cannot spell – Falstone – all buried at Norham. Her mother’s family used to go to Spittal Church, so some of their registers will be there… In her next letter of 9th August 1912, she follows up with the following account: Leonard Taylor James Taylor, butcher, Eyemouth ***** Marjorie Taylor m. George Sanderson, weaver Norham ***** Ann Taylor m. Hoffman, a soldier at Berwick. [of whom I have written before in Tennis & a Teapot] ***** Sarah Taylor m. John Huish. He died from burns received at Kimmerston Hall when it was burned down. Sarah died at Berry Hill. [Sarah’s husband was actually called Ralph, not John, and she died at Harperidge, (Donaldsons Lodge) the home of her daughter Sarah rather than Berry Hill (Ford & Etal)] ***** Elizabeth Taylor m. Bolton, Horncliffe and her daughter married a Turner, Horncliffe ***** Margaret Taylor m. William Lyle, Felkington. Her daughter m. Peter Dodds and her granddaughter is now in Horncliffe. It would seem there is some confusion surrounding Sarah Taylor and her spouse, and knowing what I now know, I suspect Ms Nicholson, or her informant was trying their best at a cover up by laying a bit of a smokescreen. The fact of the matter is that Ralph Hush junior, son of Sarah Taylor and Ralph Hush senior was a convicted felon, who narrowly escaped the hangman’s noose, when his sentence of death for stealing sheep was commuted to transportation for life. The case has been written about extensively, much of which can be found online not least in the Australian convict records (which includes some rather spurious information) but also on his own Wiki page!  John Smith owns this book, God give him grace on it to look, And if this book do chance to find, This write will show that it is min, And if he be onest man, He will restore to me again, And I will thank him for his paines, As long as life in me remains, 1690, John Smith with my hand this day at Cornhill April the first. (Transcribed from Family Bible by George Aynsley Smith in 1915) One of these fine days it would be nice to read about some positive antics of ancestral relatives, but in the meantime I will happily take the odd criminal or two, or three as they add a considerable amount of ‘colour’. There is much more digging to do in this tranche of DNA, as I am only just scratching the surface in the Ancestry database, let alone matches elsewhere. It is incredible to think that a second cousin four times removed, who lived so long ago may hold the key to unlocking earlier generations of the Smith family for whom we currently hold just pieces of a much bigger jigsaw. It also shows that no matter how dismal your DNA matches, stick at it, test more family members, build out your tree and work out how those mutual matches are related to each other. It will pay dividends in the end! Useful LinksFor those of you interested in learning more about using DNA for historical research, here are a few links to webinars and instructional videos by my great friend and colleague Michelle Leonard who is renowned the world over as leader in the field of genetic genealogy and as a bit of a 'genes genuis':

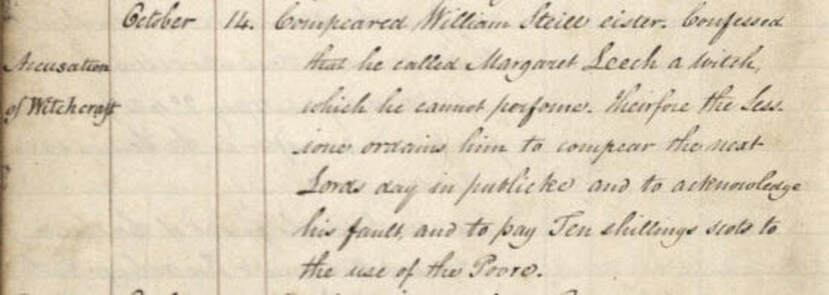

How Testing Multiple Relatives Can Turbocharge Your DNA Research - Legacy Family Tree (Free until 2 June 2021). This webinar explains the relevance of testing multiple relatives in more depth, plus a whole lot more! If you don't already subscribe to Legacy Family Tree, access to their HUGE library of top quality webinars past and present comes highly recommended and can be purchased for only $49 per annum. Michelle has no less 22 webinar tutorials amongst in excess of 1500 available in the Legacy Family Tree library. 10% discount available if you subscribe before 1 June 2021 - use code 'turbo'. #TwiceRemoved Investigates DNA Natalie Pithers of Twice Removed interviews expert genetic genealogist Michelle Leonard, who shares her amazing DNA discoveries and family history stories. From identifying the bodies of WWI soldiers to personal feelings on a grandmother that died tragically you, Michelle’s stories give a fresh perspective on using DNA for family history. Making the Most of your Autosomal DNA Test - Family Tree Live 2019, Alexandra Palace Michelle Leonard’s talk gives an overview of how autosomal DNA testing can help you solve mysteries in – and confirm the accuracy of – your family tree. DNA is Dynamite - How to Ignite your Ancestral Research (Michelle Leonard) - Genetic Genealogy Ireland.This is a talk for beginners giving an overview of the basic information required to understand the three main types of DNA testing available for ancestral research. Michelle will explain how each test works and talk you through the first steps you should take once your results arrive. There are also links to a couple of events where you can catch Michelle live in the June newsletter - if interested either contact me or subscribe to the newsletter to keep up to speed with forth coming events. Kirk Session Records |

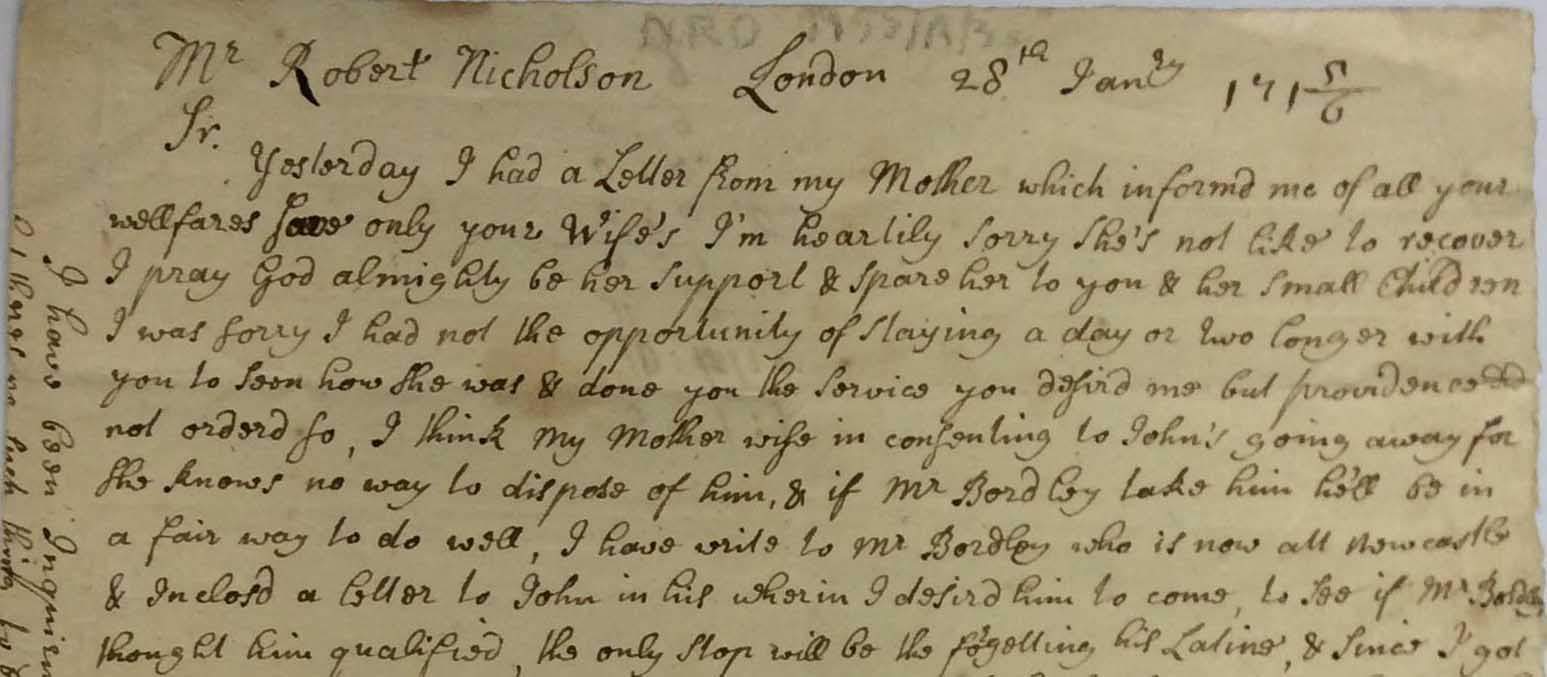

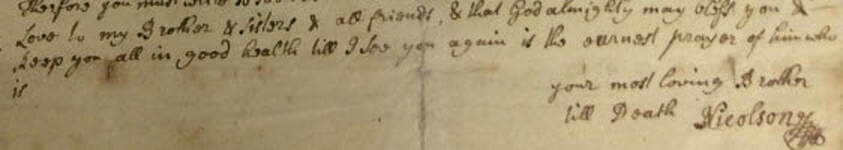

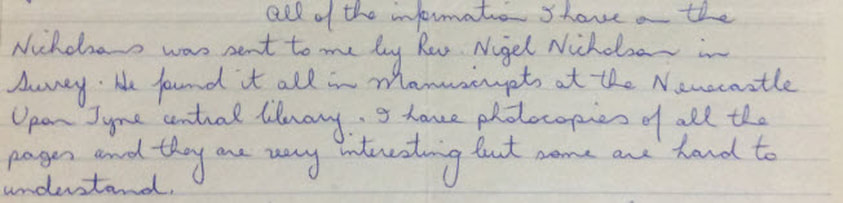

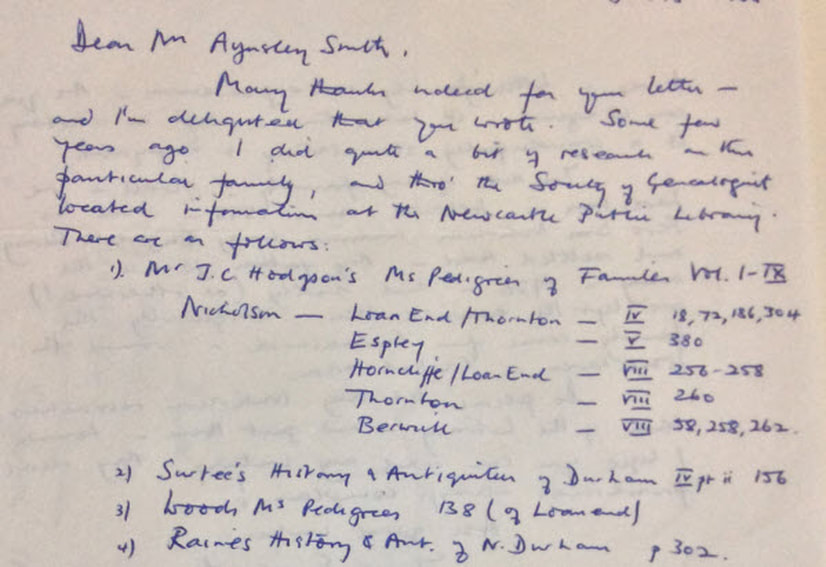

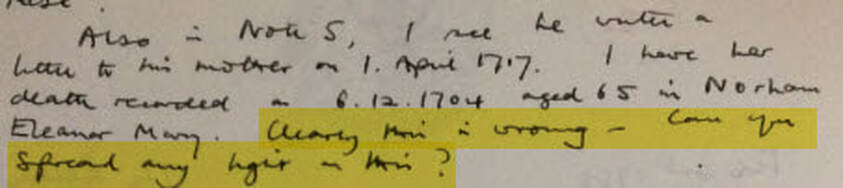

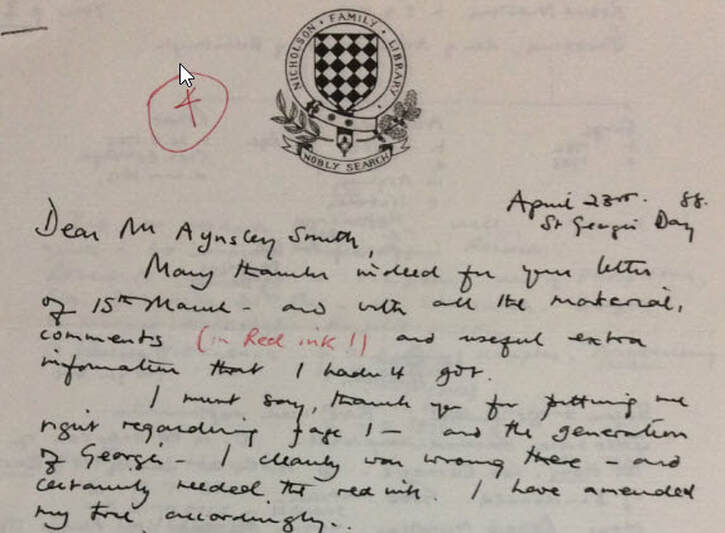

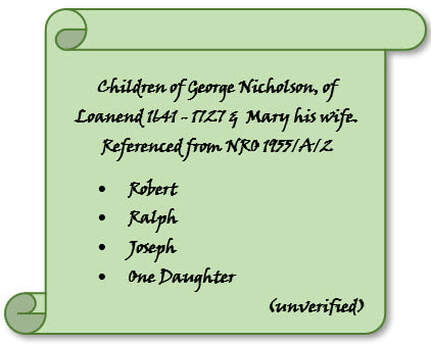

| Fortunately, this particular error has had a minimal ‘knock-on effect’. A letter written by Robert Nicholson of Loanend in 1821 states that George and Mary left four children, three sons; Ralph, Joseph and Robert, and one daughter who is unnamed. The current pedigree lists 6, but with the removal of James and his sister Margaret who married a Mr Patterson, the numbers and names would tally. The error, however, still casts doubt over the validity of other areas of the early Nicholson pedigree, which appear to be not unfounded. |

The earlier Generation – Errors & Omissions

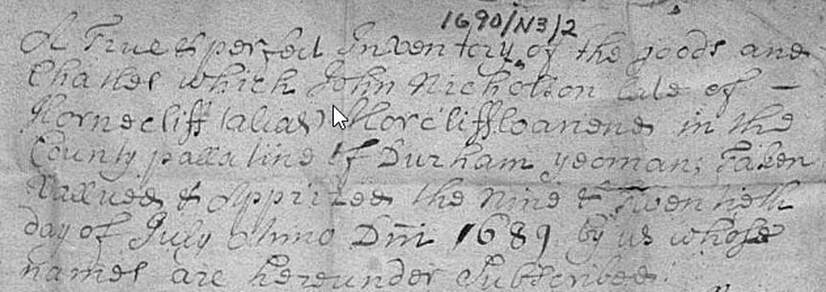

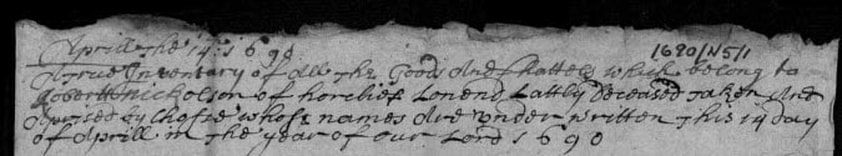

The Parentage of William Nicholson gentleman of Berwick upon Tweed died 1690.

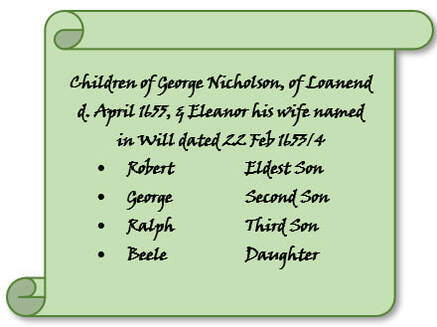

| The Pedigree has aligned William senior as a son of another George Nicholson of Loanend who died in 1655 and his wife Eleanor. However, the Will left by this George, written the 22 February 1653/4 is extremely specific with regard to the inheritance of land at Horncliffe in favour of male heirs; he names each of his three sons Robert, George and Ralph, as eldest, second and third son successively and their lawfully begotten male heirs.[6] Only after the possibility of a male heir has been exhausted was the land to pass to the heirs of his daughter Beele. |

The Missing Generation

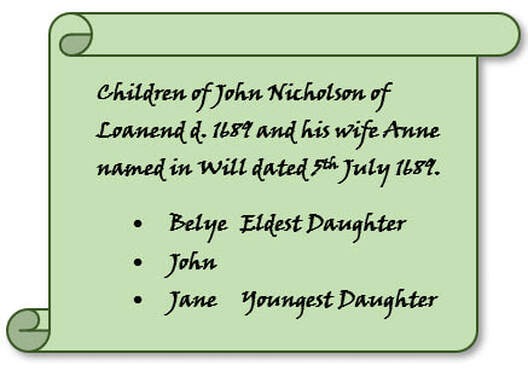

The second individual who is currently absent from the pedigree is a Robert Nicholson of Loaned who died sometime before his Inventory was prepared on the 14 April.[7]

So, who were James Nicholson of Maryland’s Parents?

Top Tip!

[2] The Rev Canon Nigel Nicholson & Mrs Rosemary Kitson, ‘Nicholson being a Compilation of Family trees of Nichsolon and Nicolson …’, Gateshead, 2003, Vol II. p.554; Michael White, ‘19th Century Pioneer:

Frank Villeneuve Nicholson Family in Australia’, Appendix I - George Nicholson of Loanend down to Frank Villeneuve Nicholson (1655 to 1898) Compiled by Kaye Mobsby p.12, Brisbane 2016; Circa 70 Ancestry Online Trees; etc.

[3] Michael White, ‘19th Century Pioneer: Frank Villeneuve Nicholson Family in Australia’, Appendix I - George Nicholson of Loanend down to Frank Villeneuve Nicholson (1655 to 1898) Compiled by Kaye Mobsby p.12, Brisbane 2016

[4] England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858 for Gulielmi Nicholson, PROB 11: Will Registers, 1713-1722, Piece 572: Shaller, Quire Numbers 1-48 (1720)

[5] North East Inheritance Database DPR/I/1/1691/N4/1-2 & DPR/I/1/1691/N4/3

[6] North East Inheritance Database DPRI/1/1664/N3

[7] North East Inheritance Database DPR/I/1/1690/N5/1-2

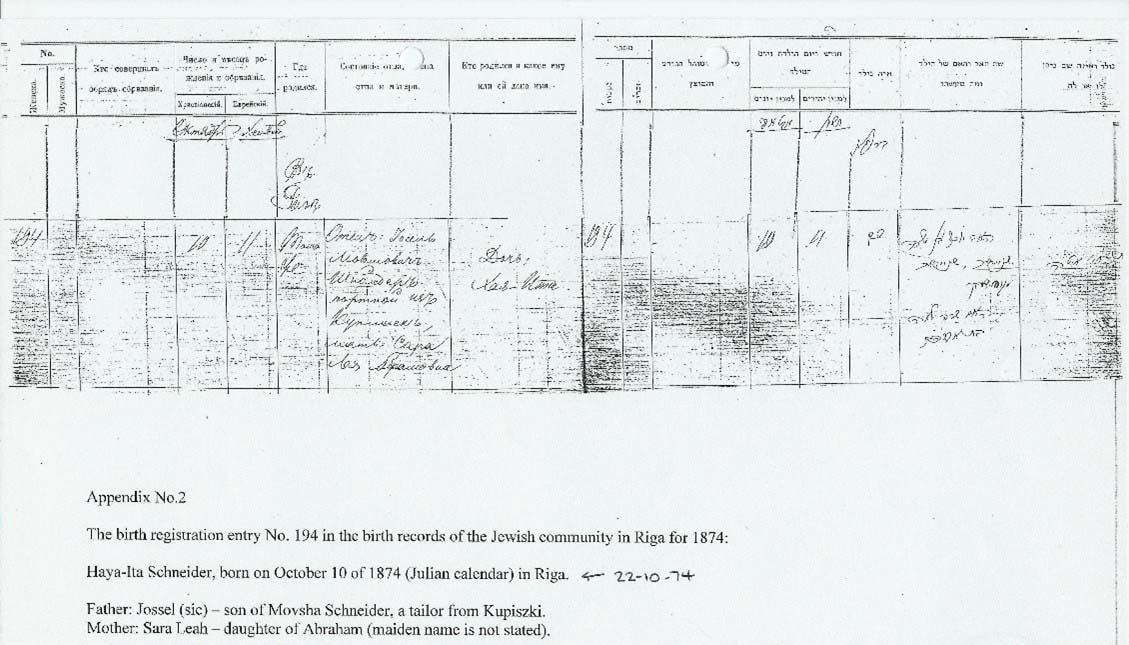

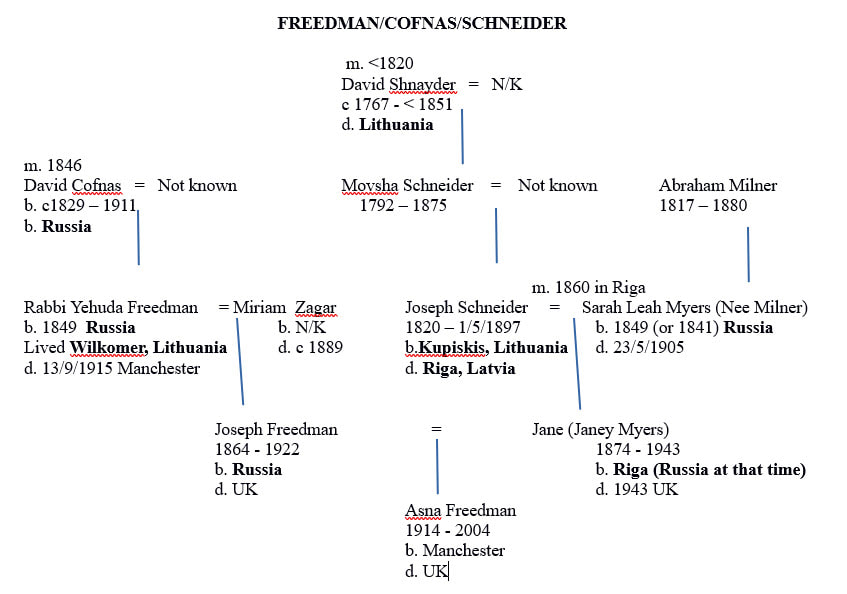

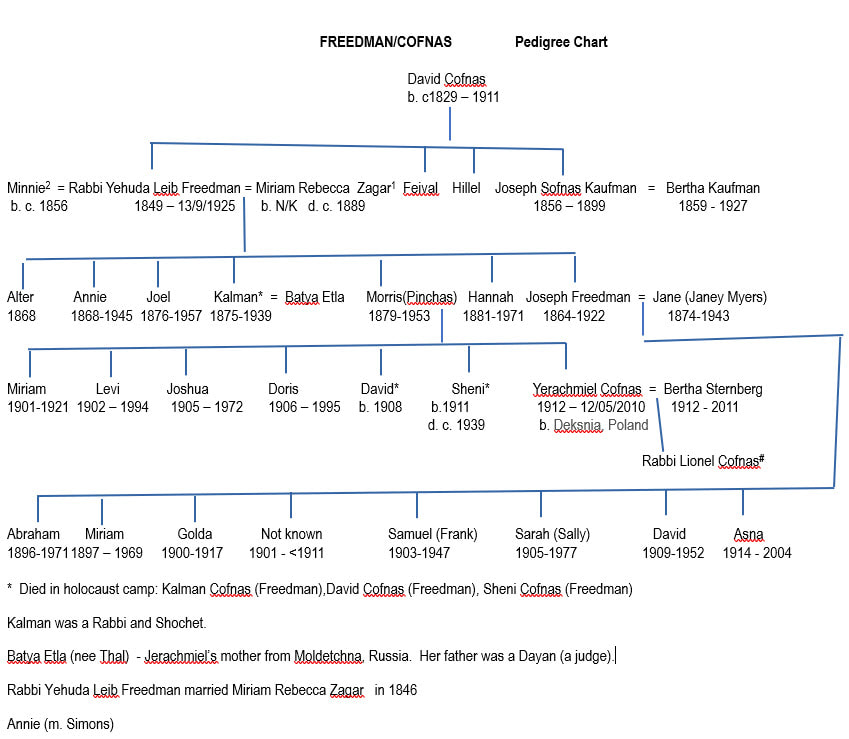

Extracts from ‘My Mother’s Story’

Memories of her young days written by Asna in 2001

Cathie once suggested I write down incidents in my life as they came to mind & this morning, Sept 18th 2001, I am doing just that. I received a notice in the post this morning from the BHA (British Humanist Assn) about a Xmas holiday in Buxton, so memories came flooding back.

My mother still only in her forties suffered from Osteo-Arthritis, then known as just Rheumatism, & each year went to Buxton for a month to 'take the treatment' hers being mainly mud applications & drinking the Spa water. The year before the death of my father he looked after me at home, but after his death when I was 8 years old my mother took me with her for possibly 2 years running until she could no longer afford the treatment though we stayed in a simple little flat.

After arrise (sic) & settling in we would go shopping, my mother buying a selection of young vegs then coming into season & would make a soup containing new carrots, peas, beans pots etc cooked slowly in milk; [we buy bread?] she always bought me a treat – a large bun of choux pastry bun (as my pudding) filled with fresh cream from a wonderful bakery.

Our next journey was down to the Pump where she would produce her little silver 'collapsible' cup to drink the so called healing waters. I waited in a queue of children all anxious to man the pump & each of us would be allowed to 'serve' a few people.